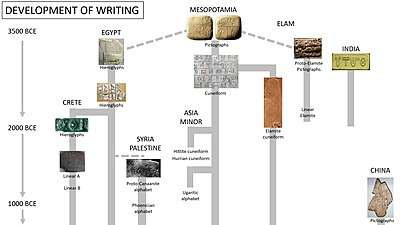

Proto-Elamite

The Proto-Elamite period, also known as Susa III, is the time from ca. 3400 BC to 2500 BC in the area of Elam.[3] In archaeological terms this corresponds to the late Banesh period, and it is recognized as the oldest civilization in Iran.

The Proto-Elamite script is an Early Bronze Age writing system briefly in use before the introduction of Elamite cuneiform.

Overview

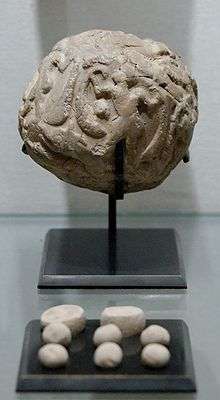

During the period 8000–3700 BC, the Fertile Crescent witnessed the spread of small settlements supported by agricultural surplus. Geometric tokens emerged to be used to manage stewardship of this surplus.[4] The earliest tokens now known are those from two sites in the Zagros region of Iran: Tepe Asiab and Ganj-i-Dareh Tepe.[5]

The Mesopotamian civilization emerged during the period 3700–2900 BC amid the development of technological innovations such as the plough, sailing boats and copper metal working. Clay tablets with pictographic characters appeared in this period to record commercial transactions performed by the temples.[4]

The most important Proto-Elamite sites are Susa and Anshan. Another important site is Tepe Sialk, where the only remaining Proto-Elamite ziggurat is still seen. Texts in the undeciphered Proto-Elamite script found in Susa are dated to this period. It is thought that the Proto-Elamites were in fact Elamites (Elamite speakers), because of the many cultural similarities (for example, the building of ziggurats), and because no large-scale migration to this area seems to have occurred between the Proto-Elamite period and the later Elamites. But because their script is yet to be deciphered, this theory remains uncertain.

Some anthropologists, such as John Alden, maintain that Proto-Elamite influence grew rapidly at the end of the 4th millennium BC and declined equally rapidly with the establishment of maritime trade in the Persian Gulf several centuries later.

Proto-Elamite pottery dating back to the last half of the 5th millennium BC has been found in Tepe Sialk, where Proto-Elamite writing, the first form of writing in Iran, has been found on tablets of this date. The first cylinder seals come from the Proto-Elamite period, as well.[6]

Striding figure, Proto-Elamite or Mesopotamian (3000-2800 BC).[7]

Striding figure, Proto-Elamite or Mesopotamian (3000-2800 BC).[7] Kneeling Bull with Vessel. Kneeling bull holding a spouted vessel, Proto-Elamite period (3100-2900 BC). Metropolitan Museum of Art[8]

Kneeling Bull with Vessel. Kneeling bull holding a spouted vessel, Proto-Elamite period (3100-2900 BC). Metropolitan Museum of Art[8] The Proto-Elamite Guennol Lioness, c.3000-2800 BC, 3.5 inches high

The Proto-Elamite Guennol Lioness, c.3000-2800 BC, 3.5 inches high Proto-Elamite vase, 2600-2300 BCE, found in Ur

Proto-Elamite vase, 2600-2300 BCE, found in Ur

Proto-Elamite script

It is uncertain whether the Proto-Elamite script was the direct predecessor of Linear Elamite. Both scripts remain largely undeciphered, and it is mere speculation to postulate a relationship between the two.

A few Proto-Elamite signs seem either to be loans from the slightly older proto-cuneiform (Late Uruk) tablets of Mesopotamia, or perhaps more likely, to share a common origin. Whereas proto-cuneiform is written in visual hierarchies, Proto-Elamite is written in an in-line style: numerical signs follow the objects they count; some non-numerical signs are 'images' of the objects they represent, although the majority are entirely abstract.

Proto-Elamite was used for a brief period around 3000 BC[12][13] (Jemdet Nasr period in Mesopotamia), whereas Linear Elamite is attested for a similarly brief period in the last quarter of the 3rd millennium BC.

Proponents of an Elamo-Dravidian relationship have looked for similarities between the Proto-Elamite script and the Indus script.[14]

Inscription corpus

The Proto-Elamite writing system was used over a very large geographical area, stretching from Susa in the west, to Tepe Yahya in the east, and perhaps beyond. The known corpus of inscriptions consists of some 1600 tablets, the vast majority unearthed at Susa.

Proto-Elamite tablets have been found at the following sites (in order of number of tablets recovered):

- Susa (more than 1500 tablets)

- Anshan, or Malyan (more than 30 tablets)

- Tepe Yahya (27 tablets)

- Tepe Sialk (22 tablets)

- Jiroft (two tablets)

- Ozbaki (one tablet)

- Shahr-e Sukhteh (one tablet)

None of the inscribed objects from Ghazir, Chogha Mish or Hissar can be verified as Proto-Elamite; the tablets from Ghazir and Choga Mish are Uruk IV style or numerical tablets, whereas the Hissar object cannot be classified at present. The majority of the Tepe Sialk tablets are also not proto-Elamite, strictly speaking, but belong to the period of close contact between Mesopotamia and Iran, presumably corresponding to Uruk V - IV.

Decipherment attempts

Although Proto-Elamite remains undeciphered, the content of many texts is known. This is possible because certain signs, and in particular a majority of the numerical signs, are similar to the neighboring Mesopotamian writing system, proto-cuneiform. In addition, a number of the proto-Elamite signs are actual images of the objects they represent. However, the majority of the proto-Elamite signs are entirely abstract, and their meanings can only be deciphered through careful graphotactical analysis.

While the Elamite language has been suggested as a likely candidate underlying the Proto-Elamite inscriptions, there is no positive evidence of this. The earliest Proto-Elamite inscriptions, being purely ideographical, do not in fact contain any linguistic information, and following Friberg's 1978/79 study of Ancient Near Eastern metrology, decipherment attempts have moved away from linguistic methods.

In 2012, Dr Jacob Dahl of the Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford, announced a project to make high-quality images of Proto-Elamite clay tablets and publish them online. His hope is that crowdsourcing by academics and amateurs working together would be able to understand the script, despite the presence of mistakes and the lack of phonetic clues.[15] Dahl assisted in making the images of nearly 1600 Proto-Elamite tablets online.[16]

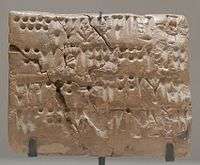

Globular envelope with a cluster of accounting tokens. Clay, Uruk period. From the Tell of the Acropolis in Susa.

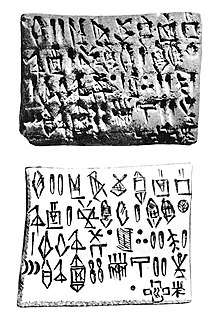

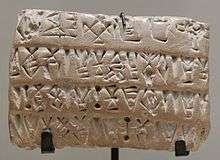

Globular envelope with a cluster of accounting tokens. Clay, Uruk period. From the Tell of the Acropolis in Susa. Economic tablet with numeric signs and Proto-Elamite script. Clay accounting tokens, Uruk period. From the Tell of the Acropolis in Susa.

Economic tablet with numeric signs and Proto-Elamite script. Clay accounting tokens, Uruk period. From the Tell of the Acropolis in Susa. Economic tablet with numeric signs and Proto-Elamite script. Clay accounting tokens, Uruk period. From the Tell of the Acropolis in Susa.

Economic tablet with numeric signs and Proto-Elamite script. Clay accounting tokens, Uruk period. From the Tell of the Acropolis in Susa.

Proto-Elamite cylinder seals

Proto-Elamite seals follow the seals of the Uruk period, with which they share many stylistic elements, but display more individuality and a more lively rendering.[17]

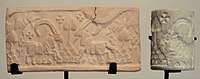

Susa III/ Proto-Elamite cylinder seal, 3150-2800 BC. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 1484

Susa III/ Proto-Elamite cylinder seal, 3150-2800 BC. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 1484 Susa III/ Proto-Elamite cylinder seal 3150-2800 BC Louvre Museum Sb 2675

Susa III/ Proto-Elamite cylinder seal 3150-2800 BC Louvre Museum Sb 2675 Susa III/ Proto-Elamite cylinder seal 3150-2800 BC Mythological being on a boat Louvre Museum Sb 6379

Susa III/ Proto-Elamite cylinder seal 3150-2800 BC Mythological being on a boat Louvre Museum Sb 6379 Proto-Elamite seal impression

Proto-Elamite seal impression

See also

References

- Louvre, Musée du (1992). The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 71 Item Nb.40. ISBN 9780870996511.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Lamberg-Karlovsky, C. C. (1971-01-01). "The Proto-Elamite Settlement at Tepe Yaḥyā". Iran. 9: 87–96. doi:10.2307/4300440. JSTOR 4300440.

- Salvador Carmona & Mahmoud Ezzamel:Accounting And Forms Of Accountability In Ancient Civilizations: Mesopotamia And Ancient Egypt, IE Business School, IE Working Paper WP05-21, 2005), p.6 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-09-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Two precursors of writing: plain and complex tokens

- "The Habib Anavian Collection: Iranian Art from the 5th Millennium B.C. to the 7th Century A.D." website of the Anavian Gallery, New York. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- "Statuette of a Striding Figure". The Art Institute of Chicago.

- "Kneeling bull holding a spouted vessel,ca. 3100–2900 B.C. Proto-Elamite". www.metmuseum.org.

- Barraclough, Geoffrey; Stone, Norman (1989). The Times Atlas of World History. Hammond Incorporated. p. 53. ISBN 9780723003045.

- Senner, Wayne M. (1991). The Origins of Writing. University of Nebraska Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780803291676.

- Boudreau, Vincent (2004). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780521838610.

- Gnanadesikan, Amalia (2008). The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet. Blackwell. p. 25. ISBN 978-1444304688.

- Hock, Hans Heinrich (2009). Language History, Language Change, and Language Relationship: An Introduction to Historical and Comparative Linguistics (2nd ed.). Mouton de Gruyter. p. 69. ISBN 978-3110214291.

- David McAlpin: "Linguistic prehistory: the Dravidian situation", in Madhav M. Deshpande and Peter Edwin Hook: Aryan and Non-Aryan in India, p.175-189

- Coughlan, Sean (2012-10-25). "Breakthrough in world's oldest undeciphered writing". The "Reflectance Transformation Imaging System" from Oxford University in use at the Louvre Museum to obtain enhanced images of the writing. BBC News Online. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative. University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1992. p. 70. ISBN 9780870996511.

Literature

- Jacob L. Dahl, "Complex Graphemes in Proto-Elamite," in Cuneiform Digital Library Journal (CDLJ) 2005:3. Download a PDF copy

- Dahl, Jacob L, "Animal Husbandry in Susa during the Proto-Elamite Period" SMEA, vol.47, pp. 81–134, 2005

- Peter Damerow, “The Origins of Writing as a Problem of Historical Epistemology,” in Cuneiform Digital Library Journal (CDLJ) 2006:1. Download a PDF copy

- Peter Damerow and Robert K. Englund, The Proto-Elamite Texts from Tepe Yahya (= The American School of Prehistoric Research Bulletin 39; Cambridge, MA, 1989).

- Englund, R.K, "The Proto-Elamite Script," in: Peter Daniels and William Bright, eds. The World's Writing Systems (1996). New York/Oxford, pp. 160–164, 1996

- Robert H. Dyson, “Early Work on the Acropolis at Susa. The Beginning of Prehistory in Iraq and Iran,” Expedition 10/4 (1968) 21-34.

- Robert K. Englund, “The State of Decipherment of Proto-Elamite,” in: Stephen Houston, ed. The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process (2004). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 100–149. Download a PDF copy

- Jöran Friberg, The Third Millennium Roots of Babylonian Mathematics I-II (Göteborg, 1978/79).

- A. Le Brun, “Recherches stratigraphiques a l’acropole de Suse, 1969-1971,” in Cahiers de la Délégation archaéologique Française en Iran 1 (= CahDAFI 1; Paris, 1971) 163 – 216.

- Piero Meriggi, La scritura proto-elamica. Parte Ia: La scritura e il contenuto dei testi (Rome, 1971).

- Piero Meriggi, La scritura proto-elamica. Parte IIa: Catalogo dei segni (Rome, 1974).

- Piero Meriggi, La scritura proto-elamica. Parte IIIa: Testi (Rome, 1974).

- Daniel T. Potts, The Archaeology of Elam (Cambridge, UK, 1999).

- Francois Vallat, The Most Ancient Scripts of Iran: The Current Situation, World Archaeology, vol. 17, no. 3, Early Writing Systems, pp. 335–347, (Feb., 1986)

External links

- Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative

- Proto-Elamite cdliwiki by the University of Oxford hosted by the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative

- Graphic, with article, of a Proto-Elamite tablet

- Art of the Bronze Age: Southeastern Iran, Western Central Asia, and the Indus Valley, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Proto-Elamite culture

- A New Edition of the Proto-Elamite Text MDP 17, 112 - Laura F. Hawkins , University of Oxford