Geʽez script

Geʽez (Geʽez: ግዕዝ, Gəʿəz) is a script used as an abugida (alphasyllabary) for several languages of Eritrea and Ethiopia. It originated as an abjad (consonant-only alphabet) and was first used to write Geʽez, now the liturgical language of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, and Beta Israel, the Jewish community in Ethiopia. In Amharic and Tigrinya, the script is often called fidäl (ፊደል), meaning "script" or "alphabet".

| Geʽez | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Languages | Semitic languages (e.g. Geʽez, Amharic, Tigrinya, Tigre, Harari, etc.), but also Bilen, Meʼen, as one of two scripts in Anuak, and unofficially in some contexts of other languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea |

Time period | c. AD 100 to present |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Amharic alphabet, Tigrinya various other alphabets of Ethiopia and Eritrea |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 | Ethi, 430 |

Unicode alias | Ethiopic |

Unicode range |

|

|

Egyptian hieroglyphs 32 c. BCE

Hangul 1443 Thaana 18 c. CE (derived from Brahmi numerals) |

The Geʽez script has been adapted to write other languages, mostly Semitic, particularly Amharic in Ethiopia, and Tigrinya in both Eritrea and Ethiopia. It is also used for Sebat Bet, Meʼen, and most other languages of Ethiopia. In Eritrea it is used for Tigre and it has traditionally been used for Bilen, a Cushitic language. Tigre, spoken in western and northern Eritrea, is considered to resemble Geʽez more than do the other derivative languages. Other Cushitic peoples in the Horn of Africa, such as Oromos, Somalis and Afars, used Latin-based orthographies.

For the representation of sounds, this article uses a system that is common (though not universal) among linguists who work on Ethiopian Semitic languages. This differs somewhat from the conventions of the International Phonetic Alphabet. See the articles on the individual languages for information on the pronunciation.

History and origins

The earliest inscriptions of Semitic languages in Eritrea and Ethiopia date to the 9th century BCE in Ancient South Arabian script, which is known as Epigraphic South Arabian (ESA), an abjad shared with contemporary kingdoms in South Arabia.

After the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, variants of the script arose, evolving in the direction of the later Geʻez abugida or alphasyllabary. This evolution can be seen most clearly in evidence from inscriptions (mainly graffiti on rocks and caves) in the Tigray Region in northern Ethiopia and the former province of Akele Guzai in Eritrea.[4]

By the first centuries CE, what is called "Old Ethiopic" or the "Old Geʻez alphabet" arose, an abjad written left-to-right (as opposed to boustrophedon like ESA) with letters basically identical to the first-order forms of the modern vocalized alphabet (e.g. "k" in the form of "kä"). There were also minor differences, such as the letter "g" facing to the right instead of to the left as in vocalized Geʻez, and a shorter left leg of "l", as in ESA, instead of equally-long legs in vocalized Geʻez (somewhat resembling the Greek letter lambda).[5] Vocalization of Geʻez occurred in the 4th century, and though the first completely vocalized texts known are inscriptions by Ezana, vocalized letters predate him by some years, as an individual vocalized letter exists in a coin of his predecessor, Wazeba of Axum.[6][7] Linguist Roger Schneider has also pointed out in an unpublished early 1990s paper anomalies in the known inscriptions of Ezana of Axum that imply that he was consciously employing an archaic style during his reign, indicating that vocalization could have occurred much earlier.[8]

As a result, some believe that the vocalization may have been adopted to preserve the pronunciation of Geʻez texts due to the already moribund or extinct status of Geʻez, and that, by that time, the common language of the people were already later Ethiopian Semitic languages. At least one of Wazeba's coins from the late 3rd or early 4th century contains a vocalized letter, some 30 or so years before Ezana.[9] Kobishchanov, Peter T. Daniels, and others have suggested possible influence from the Brahmic scripts in vocalization, as they are also abugidas, and the Kingdom of Aksum was an important part of major trade routes involving India and the Greco-Roman world throughout classical antiquity.[10][11]

According to the beliefs of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church and Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, the original consonantal form of the Geʻez fidäl was divinely revealed to Enos "as an instrument for codifying the laws", and the present system of vocalisation is attributed to a team of Aksumite scholars led by Frumentius (Abba Selama), the same missionary said to have converted King Ezana to Christianity in the 4th century.[12] It has been argued that the vowel marking pattern of the script reflects a South Asian system such as would have been known by Frumentius.[13] A separate tradition, recorded by Aleqa Taye, holds that the Geʻez consonantal alphabet was first adapted by Zegdur, a legendary king of the Agʻazyan Sabaean dynasty held to have ruled in Ethiopia c. 1300 BCE.[14]

Geʻez has 26 consonantal letters. Compared to the inventory of 29 consonants in the South Arabian alphabet, continuants are missing of ġ, ẓ, and South Arabian s3

Thus, there are 24 correspondences of Geʻez and the South Arabian alphabet:

| Translit. | h | l | ḥ | m | ś (SA s2) | r | s (SA s1) | ḳ | b | t | ḫ | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geʻez | ሀ | ለ | ሐ | መ | ሠ | ረ | ሰ | ቀ | በ | ተ | ኀ | ነ |

| South Arabian | 𐩠 | 𐩡 | 𐩢 | 𐩣 | 𐩦 | 𐩧 | 𐩪 | 𐩤 | 𐩨 | 𐩩 | 𐩭 | 𐩬 |

| Translit. | ʾ | k | w | ʿ | z (SA ḏ) | y | d | g | ṭ | ṣ | ḍ | f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geʻez | አ | ከ | ወ | ዐ | ዘ | የ | ደ | ገ | ጠ | ጸ | ፀ | ፈ |

| South Arabian | 𐩱 | 𐩫 | 𐩥 | 𐩲 | 𐩹 | 𐩺 | 𐩵 | 𐩴 | 𐩷 | 𐩮 | 𐩳 | 𐩰 |

Many of the letter names are cognate with those of Phoenician, and may thus be assumed for the Proto-Sinaitic script.

Geʽez alphabets

Two alphabets were used to write the Geʽez language, an abjad and later an abugida.

Geʽez abjad

The abjad, used until c. 330 AD, had 26 consonantal letters:

- h, l, ḥ, m, ś, r, s, ḳ, b, t, ḫ, n, ʾ, k, w, ʿ, z, y, d, g, ṭ, p̣, ṣ, ṣ́, f, p

| Translit. | h | l | ḥ | m | ś | r | s | ḳ | b | t | ḫ | n | ʾ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geʽez | ሀ | ለ | ሐ | መ | ሠ | ረ | ሰ | ቀ | በ | ተ | ኀ | ነ | አ |

| Translit. | k | w | ʿ | z | y | d | g | ṭ | p̣ | ṣ | ṣ́ | f | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geʽez | ከ | ወ | ዐ | ዘ | የ | ደ | ገ | ጠ | ጰ | ጸ | ፀ | ፈ | ፐ |

Vowels were not indicated.

Geʽez abugida

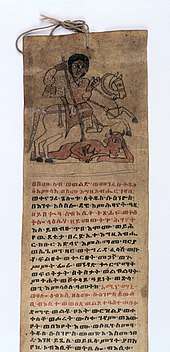

%2C_15th_century_(The_S.S._Teacher's_Edition-The_Holy_Bible_-_Plate_XII%2C_1).jpg)

Modern Geʽez is written from left to right.

The Geʽez abugida developed under the influence of Christian scripture by adding obligatory vocalic diacritics to the consonantal letters. The diacritics for the vowels, u, i, a, e, ə, o, were fused with the consonants in a recognizable but slightly irregular way, so that the system is laid out as a syllabary. The original form of the consonant was used when the vowel was ä (/ə/), the so-called inherent vowel. The resulting forms are shown below in their traditional order. For some vowels, there is an eighth form for the diphthong -wa or -oa; and for some of those, a ninth for -yä.

To represent a consonant with no following vowel, for example at the end of a syllable or in a consonant cluster, the ə (/ɨ/) form is used (the letter in the sixth column).

| ä [ə] or [a] | u | i | a | e | ə [ɨ] | o | wa | yä [jə] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoy | h | ሀ | ሁ | ሂ | ሃ | ሄ | ህ | ሆ | ||

| Läwe | l | ለ | ሉ | ሊ | ላ | ሌ | ል | ሎ | ሏ | |

| Ḥäwt | ḥ | ሐ | ሑ | ሒ | ሓ | ሔ | ሕ | ሖ | ሗ | |

| May | m | መ | ሙ | ሚ | ማ | ሜ | ም | ሞ | ሟ | ፙ |

| Śäwt | ś | ሠ | ሡ | ሢ | ሣ | ሤ | ሥ | ሦ | ሧ | |

| Rəʾs | r | ረ | ሩ | ሪ | ራ | ሬ | ር | ሮ | ሯ | ፘ |

| Sat | s | ሰ | ሱ | ሲ | ሳ | ሴ | ስ | ሶ | ሷ | |

| Ḳaf | ḳ | ቀ | ቁ | ቂ | ቃ | ቄ | ቅ | ቆ | ቋ | |

| Bet | b | በ | ቡ | ቢ | ባ | ቤ | ብ | ቦ | ቧ | |

| Täwe | t | ተ | ቱ | ቲ | ታ | ቴ | ት | ቶ | ቷ | |

| Ḫarm | ḫ | ኀ | ኁ | ኂ | ኃ | ኄ | ኅ | ኆ | ኋ | |

| Nähas | n | ነ | ኑ | ኒ | ና | ኔ | ን | ኖ | ኗ | |

| ʼÄlf | ʾ | አ | ኡ | ኢ | ኣ | ኤ | እ | ኦ | ኧ | |

| Kaf | k | ከ | ኩ | ኪ | ካ | ኬ | ክ | ኮ | ኳ | |

| Wäwe | w | ወ | ዉ | ዊ | ዋ | ዌ | ው | ዎ | ||

| ʽÄyn | ʽ | ዐ | ዑ | ዒ | ዓ | ዔ | ዕ | ዖ | ||

| Zäy | z | ዘ | ዙ | ዚ | ዛ | ዜ | ዝ | ዞ | ዟ | |

| Yämän | y | የ | ዩ | ዪ | ያ | ዬ | ይ | ዮ | ||

| Dänt | d | ደ | ዱ | ዲ | ዳ | ዴ | ድ | ዶ | ዷ | |

| Gäml | g | ገ | ጉ | ጊ | ጋ | ጌ | ግ | ጎ | ጓ | |

| Ṭäyt | ṭ | ጠ | ጡ | ጢ | ጣ | ጤ | ጥ | ጦ | ጧ | |

| P̣äyt | p̣ | ጰ | ጱ | ጲ | ጳ | ጴ | ጵ | ጶ | ጷ | |

| Ṣädäy | ṣ | ጸ | ጹ | ጺ | ጻ | ጼ | ጽ | ጾ | ጿ | |

| Ṣ́äppä | ṣ́ | ፀ | ፁ | ፂ | ፃ | ፄ | ፅ | ፆ | ||

| Äf | f | ፈ | ፉ | ፊ | ፋ | ፌ | ፍ | ፎ | ፏ | ፚ |

| Psa | p | ፐ | ፑ | ፒ | ፓ | ፔ | ፕ | ፖ | ፗ | |

Labiovelar variants

The letters for the labialized velar consonants are variants of the non-labialized velar consonants:

| Consonant | ḳ | ḫ | k | g |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ቀ | ኀ | ከ | ገ | |

| Labialized variant | ḳʷ | ḫʷ | kʷ | gʷ |

| ቈ | ኈ | ኰ | ጐ |

Unlike the other consonants, these labiovelar ones can only be combined with five different vowels:

| ä | i | a | e | ə | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ḳʷ | ቈ | ቊ | ቋ | ቌ | ቍ |

| ḫʷ | ኈ | ኊ | ኋ | ኌ | ኍ |

| kʷ | ኰ | ኲ | ኳ | ኴ | ኵ |

| gʷ | ጐ | ጒ | ጓ | ጔ | ጕ |

Adaptations to other languages

The Geʽez abugida has been adapted to several modern languages of Eritrea and Ethiopia, frequently requiring additional letters.

Additional letters

Some letters were modified to create additional consonants for use in languages other than Geʽez. This is typically done by adding a horizontal line at the top of a similar-sounding consonant. The pattern is most commonly used to mark a palatalized version of the original consonant.

| Consonant | b | t | d | ṭ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| በ | ተ | ደ | ጠ | |

| Affricated variant | v [v] | č [t͡ʃ] | ǧ [d͡ʒ] | č̣ [t͡ʃʼ] |

| ቨ | ቸ | ጀ | ጨ |

| Consonant | ḳ | k |

|---|---|---|

| ቀ | ከ | |

| Affricated variant | ḳʰ [q] | x [x] |

| ቐ | ኸ | |

| Labialized variant | ḳhw [qʷ] | xʷ [xʷ] |

| ቘ | ዀ |

| Consonant | s | n | z |

|---|---|---|---|

| ሰ | ነ | ዘ | |

| Palatalized variant | š [ʃ] | ñ [ɲ] | ž [ʒ] |

| ሸ | ኘ | ዠ |

| Consonant | g | gʷ |

|---|---|---|

| ገ | ጐ | |

| Nasal variant | [ŋ] | [ŋʷ] |

| ጘ | ⶓ |

The vocalised forms are shown below. Like the other labiovelars, these labiovelars can only be combined with five vowels.

| ä | u | i | a | e | ə | o | wa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| š | ሸ | ሹ | ሺ | ሻ | ሼ | ሽ | ሾ | ሿ |

| ḳʰ | ቐ | ቑ | ቒ | ቓ | ቔ | ቕ | ቖ | |

| ḳhw | ቘ | ቝ | ቛ | ቜ | ቚ | |||

| v | ቨ | ቩ | ቪ | ቫ | ቬ | ቭ | ቮ | ቯ |

| č | ቸ | ቹ | ቺ | ቻ | ቼ | ች | ቾ | ቿ |

| [ŋʷ] | ⶓ | ⶔ | ⶕ | ⶖ |

| ä | u | i | a | e | ə | o | wa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ñ | ኘ | ኙ | ኚ | ኛ | ኜ | ኝ | ኞ | ኟ |

| x | ኸ | ኹ | ኺ | ኻ | ኼ | ኽ | ኾ | |

| xʷ | ዀ | ዂ | ዃ | ዄ | ዅ | |||

| ž | ዠ | ዡ | ዢ | ዣ | ዤ | ዥ | ዦ | ዧ |

| ǧ | ጀ | ጁ | ጂ | ጃ | ጄ | ጅ | ጆ | ጇ |

| [ŋ] | ጘ | ጙ | ጚ | ጛ | ጜ | ጝ | ጞ | ጟ |

| č̣ | ጨ | ጩ | ጪ | ጫ | ጬ | ጭ | ጮ | ጯ |

Letters used in modern alphabets

The Amharic alphabet uses all the basic consonants plus the ones indicated below. Some of the Geʽez labiovelar variants are also used.

Tigrinya has all the basic consonants, the Geʽez labiovelar letter variants, except for ḫʷ (ኈ), plus the ones indicated below. A few of the basic consonants are falling into disuse in Eritrea. See Tigrinya language#Writing system for details.

Tigre uses the basic consonants except for ś (ሠ), ḫ (ኀ) and ḍ (ፀ). It also uses the ones indicated below. It does not use the Geʽez labiovelar letter variants.

Bilen uses the basic consonants except for ś (ሠ), ḫ (ኀ) and ḍ (ፀ). It also uses the ones indicated below and the Geʽez labiovelar letter variants.

| š | ḳʰ | ḳʰʷ | v | č | ŋʷ | ñ | x | xʷ | ž | ǧ | ŋ | č̣ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ሸ | ቐ | ቘ | ቨ | ቸ | ⶓ | ኘ | ኸ | ዀ | ዠ | ጀ | ጘ | ጨ | |

| Amharic alphabet | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Tigrinya alphabet | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Tigre alphabet | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Bilen alphabet | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Note: "V" is used for words of foreign origin except for in some Gurage languages, e.g. cravat 'tie' from French. "X" is pronounced as "h" in Amharic.

List order

For Geʽez, Amharic, Tigrinya and Tigre, the usual sort order is called halähamä (h–l–ħ–m). Where the labiovelar variants are used, these come immediately after the basic consonant and are followed by other variants. In Tigrinya, for example, the letters based on ከ come in this order: ከ, ኰ, ኸ, ዀ. In Bilen, the sorting order is slightly different.

The alphabetical order is similar to that found in other South Semitic scripts, as well as in the ancient Ugaritic alphabet, which attests both the southern Semitic h-l-ħ-m order and the northern Semitic ʼ–b–g–d (abugida) order over three thousand years ago.

Other usage

Geʽez is a sacred script in the Rastafari movement. Roots reggae musicians have used it in album art.

The films 500 Years Later (፭፻-ዓመታት በኋላ) and Motherland (እናት ሀገር) are two mainstream Western documentaries to use Geʽez characters in the titles. The script also appears in the trailer and promotional material of the films.

Numerals

Geʽez uses an additional alphabetic numeral system comparable to the Hebrew, Arabic abjad and Greek numerals. It differs from these systems, however, in that it lacks individual characters for the multiples of 100. For example, 475 is written ፬፻፸፭, that is "4-100-75", and 83,692 is ፰፼፴፮፻፺፪ "8-10,000-36-100-92". Numbers are over- and underlined with a vinculum; in proper typesetting these combine to make a single bar, but some less sophisticated fonts cannot render this and show separate bars above and below each character.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 × 1 ፩ ፪ ፫ ፬ ፭ ፮ ፯ ፰ ፱ × 10 ፲ ፳ ፴ ፵ ፶ ፷ ፸ ፹ ፺ × 100 ፻ × 10,000 ፼

Ethiopian numerals were borrowed from the Greek numerals, possibly via Coptic uncial letters.[15]

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 Ethiopic ፩ ፪ ፫ ፬ ፭ ፮ ፯ ፰ ፱ ፲ ፳ ፴ ፵ ፶ ፷ ፸ ፹ ፺ ፻ Greek Α Β Γ Δ Ε Ϛ Ζ Η Θ Ι Κ Λ Μ Ν Ξ Ο Π Ϙ Ρ Coptic Ⲁ Ⲃ Ⲅ Ⲇ Ⲉ Ⲋ Ⲍ Ⲏ Ⲑ Ⲓ Ⲕ Ⲗ Ⲙ Ⲛ Ⲝ Ⲟ Ⲡ Ϥ Ⲣ

Punctuation

Punctuation, much of it modern, includes

- ፠ section mark

- ፡ word separator

- ። full stop (period)

- ፣ comma

- ፤ colon

- ፥ semicolon

- ፦ preface colon. Uses:[16]

- In transcribed interviews, after the name of the speaker whose transcribed speech immediately follows; compare the colon in western text

- In ordered lists, after the ordinal symbol (such as a letter or number), separating it from the text of the item; compare the colon, period, or right parenthesis in western text

- Many other functions of the colon in western text

- ፧ question mark

- ፨ paragraph separator

Unicode

Ethiopic has been assigned Unicode 3.0 codepoints between U+1200 and U+137F (decimal 4608–4991), containing the consonantal letters for Geʽez, Amharic and Tigrinya, punctuation and numerals. Additionally, in Unicode 4.1, there is the supplement range from U+1380 to U+139F (decimal 4992–5023) containing letters for Sebat Bet and tonal marks, and the extended range between U+2D80 and U+2DDF (decimal 11648–11743) containing letters needed for writing Sebat Bet, Meʼen and Bilen. Finally in Unicode 6.0, there is the extended-A range from U+AB00 to U+AB2F (decimal 43776–43823) containing letters for Gamo-Gofa-Dawro, Basketo and Gumuz.

| Ethiopic[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+120x | ሀ | ሁ | ሂ | ሃ | ሄ | ህ | ሆ | ሇ | ለ | ሉ | ሊ | ላ | ሌ | ል | ሎ | ሏ |

| U+121x | ሐ | ሑ | ሒ | ሓ | ሔ | ሕ | ሖ | ሗ | መ | ሙ | ሚ | ማ | ሜ | ም | ሞ | ሟ |

| U+122x | ሠ | ሡ | ሢ | ሣ | ሤ | ሥ | ሦ | ሧ | ረ | ሩ | ሪ | ራ | ሬ | ር | ሮ | ሯ |

| U+123x | ሰ | ሱ | ሲ | ሳ | ሴ | ስ | ሶ | ሷ | ሸ | ሹ | ሺ | ሻ | ሼ | ሽ | ሾ | ሿ |

| U+124x | ቀ | ቁ | ቂ | ቃ | ቄ | ቅ | ቆ | ቇ | ቈ | ቊ | ቋ | ቌ | ቍ | |||

| U+125x | ቐ | ቑ | ቒ | ቓ | ቔ | ቕ | ቖ | ቘ | ቚ | ቛ | ቜ | ቝ | ||||

| U+126x | በ | ቡ | ቢ | ባ | ቤ | ብ | ቦ | ቧ | ቨ | ቩ | ቪ | ቫ | ቬ | ቭ | ቮ | ቯ |

| U+127x | ተ | ቱ | ቲ | ታ | ቴ | ት | ቶ | ቷ | ቸ | ቹ | ቺ | ቻ | ቼ | ች | ቾ | ቿ |

| U+128x | ኀ | ኁ | ኂ | ኃ | ኄ | ኅ | ኆ | ኇ | ኈ | ኊ | ኋ | ኌ | ኍ | |||

| U+129x | ነ | ኑ | ኒ | ና | ኔ | ን | ኖ | ኗ | ኘ | ኙ | ኚ | ኛ | ኜ | ኝ | ኞ | ኟ |

| U+12Ax | አ | ኡ | ኢ | ኣ | ኤ | እ | ኦ | ኧ | ከ | ኩ | ኪ | ካ | ኬ | ክ | ኮ | ኯ |

| U+12Bx | ኰ | ኲ | ኳ | ኴ | ኵ | ኸ | ኹ | ኺ | ኻ | ኼ | ኽ | ኾ | ||||

| U+12Cx | ዀ | ዂ | ዃ | ዄ | ዅ | ወ | ዉ | ዊ | ዋ | ዌ | ው | ዎ | ዏ | |||

| U+12Dx | ዐ | ዑ | ዒ | ዓ | ዔ | ዕ | ዖ | ዘ | ዙ | ዚ | ዛ | ዜ | ዝ | ዞ | ዟ | |

| U+12Ex | ዠ | ዡ | ዢ | ዣ | ዤ | ዥ | ዦ | ዧ | የ | ዩ | ዪ | ያ | ዬ | ይ | ዮ | ዯ |

| U+12Fx | ደ | ዱ | ዲ | ዳ | ዴ | ድ | ዶ | ዷ | ዸ | ዹ | ዺ | ዻ | ዼ | ዽ | ዾ | ዿ |

| U+130x | ጀ | ጁ | ጂ | ጃ | ጄ | ጅ | ጆ | ጇ | ገ | ጉ | ጊ | ጋ | ጌ | ግ | ጎ | ጏ |

| U+131x | ጐ | ጒ | ጓ | ጔ | ጕ | ጘ | ጙ | ጚ | ጛ | ጜ | ጝ | ጞ | ጟ | |||

| U+132x | ጠ | ጡ | ጢ | ጣ | ጤ | ጥ | ጦ | ጧ | ጨ | ጩ | ጪ | ጫ | ጬ | ጭ | ጮ | ጯ |

| U+133x | ጰ | ጱ | ጲ | ጳ | ጴ | ጵ | ጶ | ጷ | ጸ | ጹ | ጺ | ጻ | ጼ | ጽ | ጾ | ጿ |

| U+134x | ፀ | ፁ | ፂ | ፃ | ፄ | ፅ | ፆ | ፇ | ፈ | ፉ | ፊ | ፋ | ፌ | ፍ | ፎ | ፏ |

| U+135x | ፐ | ፑ | ፒ | ፓ | ፔ | ፕ | ፖ | ፗ | ፘ | ፙ | ፚ | ፝ | ፞ | ፟ | ||

| U+136x | ፠ | ፡ | ። | ፣ | ፤ | ፥ | ፦ | ፧ | ፨ | ፩ | ፪ | ፫ | ፬ | ፭ | ፮ | ፯ |

| U+137x | ፰ | ፱ | ፲ | ፳ | ፴ | ፵ | ፶ | ፷ | ፸ | ፹ | ፺ | ፻ | ፼ | |||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Ethiopic Supplement[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+138x | ᎀ | ᎁ | ᎂ | ᎃ | ᎄ | ᎅ | ᎆ | ᎇ | ᎈ | ᎉ | ᎊ | ᎋ | ᎌ | ᎍ | ᎎ | ᎏ |

| U+139x | ᎐ | ᎑ | ᎒ | ᎓ | ᎔ | ᎕ | ᎖ | ᎗ | ᎘ | ᎙ | ||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Ethiopic Extended[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+2D8x | ⶀ | ⶁ | ⶂ | ⶃ | ⶄ | ⶅ | ⶆ | ⶇ | ⶈ | ⶉ | ⶊ | ⶋ | ⶌ | ⶍ | ⶎ | ⶏ |

| U+2D9x | ⶐ | ⶑ | ⶒ | ⶓ | ⶔ | ⶕ | ⶖ | |||||||||

| U+2DAx | ⶠ | ⶡ | ⶢ | ⶣ | ⶤ | ⶥ | ⶦ | ⶨ | ⶩ | ⶪ | ⶫ | ⶬ | ⶭ | ⶮ | ||

| U+2DBx | ⶰ | ⶱ | ⶲ | ⶳ | ⶴ | ⶵ | ⶶ | ⶸ | ⶹ | ⶺ | ⶻ | ⶼ | ⶽ | ⶾ | ||

| U+2DCx | ⷀ | ⷁ | ⷂ | ⷃ | ⷄ | ⷅ | ⷆ | ⷈ | ⷉ | ⷊ | ⷋ | ⷌ | ⷍ | ⷎ | ||

| U+2DDx | ⷐ | ⷑ | ⷒ | ⷓ | ⷔ | ⷕ | ⷖ | ⷘ | ⷙ | ⷚ | ⷛ | ⷜ | ⷝ | ⷞ | ||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Ethiopic Extended-A[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+AB0x | ꬁ | ꬂ | ꬃ | ꬄ | ꬅ | ꬆ | ꬉ | ꬊ | ꬋ | ꬌ | ꬍ | ꬎ | ||||

| U+AB1x | ꬑ | ꬒ | ꬓ | ꬔ | ꬕ | ꬖ | ||||||||||

| U+AB2x | ꬠ | ꬡ | ꬢ | ꬣ | ꬤ | ꬥ | ꬦ | ꬨ | ꬩ | ꬪ | ꬫ | ꬬ | ꬭ | ꬮ | ||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Literature

- Azeb Amha. 2010. On loans and additions to the fidäl (Ethiopic) writing system. in The Idea of Writing: Play and Complexity, Alexander J. de Voogt, Irving L. Finkel (editors), 179-196. Brill.

- Marcel Cohen, "La prononciation traditionnelle du Guèze (éthiopien classique)", in: Journal asiatique (1921) Sér. 11 / T. 18.

- Gabe F. Scelta, The Comparative Origin and Usage of the Ge'ez writing system of Ethiopia (2001)

References

- Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. "First Alphabet Found in Egypt", Archaeology 53, Issue 1 (Jan./Feb. 2000): 21.

- Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William, eds. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press, Inc. pp. 89, 98, 569–570. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- Gragg, Gene (2004). "Geʽez (Aksum)". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-521-56256-0.

- Rodolfo Fattovich, "Akkälä Guzay" in Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C. Wiesbaden, Otto Harrassowitz, 2003, p. 169.

- Etienne Bernand, A. J. Drewes, and Roger Schneider, "Recueil des inscriptions de l'Ethiopie des périodes pré-axoumite et axoumite, tome I". Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Paris, Boccard, 1991.

- Grover Hudson, Aspects of the history of Ethiopic writing in "Bulletin of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies 25", pp. 1-12.

- Stuart Munro-Hay. Aksum: A Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh, University Press. 1991. ISBN 978-0-7486-0106-6.

- "Geʻez translations". Ethiopic Translation and Localization Services. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, p. 207.

- Yuri M. Kobishchanov. Axum (Joseph W. Michels, editor; Lorraine T. Kapitanoff, translator). University Park, Pennsylvania, Penn State University Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0-271-00531-7.

- Peter T. Daniels, William Bright, "The World's Writing Systems", Oxford University Press. Oxford, 1996.

- Official website of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church

- Peter Unseth. Missiology and Orthography: The Unique Contribution of Christian Missionaries in Devising New Scripts. Missiology 36.3: 357-371.

- Aleqa Taye, History of the Ethiopian People, 1914

- "Ethiopian numerals Coptic" at Google Books

- "Notes on Ethiopic Localization". The Abyssinia Gateway. 2013-07-22. Archived from the original on 2014-09-10. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

External links

- Chart correlating IPA values for the Amharic alphabet

- Unicode specification

- A Look at Ethiopic Numerals

- The Names of Geʽez Letters