Human rights in Iran

The state of human rights in Iran has been criticized both by Iranians and international human rights activists, writers, and NGOs since long before the formation of the current state of Iran. The United Nations General Assembly and the Human Rights Commission[1] have condemned prior and ongoing abuses in Iran in published critiques and several resolutions. The government of Iran is criticized both for restrictions and punishments that follow the Islamic Republic's constitution and law, and for actions that do not, such as the torture, rape, and killing of political prisoners, and the beatings and killings of dissidents and other civilians.[2]

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Iran |

| Government of Islamic Republic of Iran |

|

Leadership |

|

Executive |

|

|

Supreme Councils |

|

Local governments

|

|

|

|

|

Outside government |

|

While the monarchy under the rule of the shahs had a generally abysmal human rights record according to most Western watchdog organizations, the current Islamic Republic does not have a positive reputation either, with its human rights record under the administration of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad considered to have "deteriorated markedly," according to Human Rights Watch.[3] Following the 2009 election protests there were reports of killing of demonstrators, the torture, rape and killing of detained protesters,[4][5] and the arrest and publicized mass trials of dozens of prominent opposition figures in which defendants "read confessions that bore every sign of being coerced."[6][7][8] In October 2012 the United Nations human rights office stated Iranian authorities had engaged in a "severe clampdown" on journalists and human rights advocates.[9]

Restrictions and punishments in the Islamic Republic of Iran which violate international human rights norms include harsh penalties for crimes, punishment of victimless crimes such as fornication and homosexuality, execution of offenders under 18 years of age, restrictions on freedom of speech and the press (including the imprisonment of journalists and political cartoonists), and restrictions on freedom of religion and gender equality in the Islamic Republic's Constitution (especially attacks on members of the Bahá'í religion). Reported abuses falling outside of the laws of the Islamic Republic that have been condemned include the execution of thousands of political prisoners in 1988, and the widespread use of torture to extract repudiations by prisoners of their cause and comrades on video for propaganda purposes.[10] Also condemned has been firebombings of newspaper offices and attacks on political protesters by "quasi-official organs of repression," particularly "Hezbollah," and the murder of dozens of government opponents in the 1990s, allegedly by "rogue elements" of the government.

Officials of the Islamic Republic have responded to criticism by stating that Iran has "the best human rights record" in the Muslim world;[11] that it is not obliged to follow "the West's interpretation" of human rights;[12] and that the Islamic Republic is a victim of "biased propaganda of enemies" which is "part of a greater plan against the world of Islam".[13] According to Iranian officials, those who human rights activists say are peaceful political activists being denied due process rights are actually guilty of offenses against the national security of the country,[14] and those protesters claiming Ahmadinejad stole the 2009 election are actually part of a foreign-backed plot to topple Iran's leaders.[15]

In 2018, the US and European Union imposed sanctions on several Iranian groups and officials it accused of human rights abuses.[16][17]

Background

The Imperial State of Iran, the government of Iran during the Pahlavi dynasty, lasted from 1925 to 1979. During that time two monarchs – Reza Shah Pahlavi and his son Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi – employed secret police, torture, and executions to stifle political dissent.

The Pahlavi dynasty has sometimes been described as a "royal dictatorship".[18] or "one man rule".[19] According to one history of the use of torture by the state in Iran, abuse of prisoners varied at times during the Pahlavi reign.[20]

Reza Shah era

The reign of Reza Shah was authoritarian and dictatorial at a time when authoritarian governments and dictatorships were common in both the region and the world and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was some years away.[21] Freedom of the press, workers' rights, and political freedoms were restricted under Reza Shah. Independent newspapers were closed down, political parties – even the loyal Revival party were banned. The government banned all trade unions in 1927, and arrested 150 labor organizers between 1927 and 1932.[22]

Physical force was used against some kinds of prisoners – common criminals, suspected spies, and those accused of plotting regicide. Burglars in particular were subjected to the bastinado (beating the soles of the feet), and the strappado (suspended in the air by means of a rope tied around the victims arms) to "reveal their hidden loot". Suspected spies and assassins were "beaten, deprived of sleep, and subjected to the qapani" (the binding of arms tightly behind the back) which sometimes caused a joint to crack. But for political prisoners – who were primarily Communists – there was a "conspicuous absence of torture" under Reza Shah's rule.[23] The main form of pressure was solitary confinement and the withholding of "books, newspapers, visitors, food packages, and proper medical care". While often threatened with the qapani, political prisoners "were rarely subjected to it."[24]

Mohammad Reza Shah era

Mohammad Reza became monarch after his father was deposed by Soviets and Americans in 1941. Political prisoners (mostly Communists) were released by the occupying powers, and the shah (crown prince at the time) no longer had control of the parliament.[25] But after an attempted assassination of the Shah in 1949, he was able to declare martial law, imprison communists and other opponents, and restrict criticism of the royal family in the press.[26]

Following the pro-Shah coup d'état that overthrew the Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in 1953, the Shah again cracked down on his opponents, and political freedom waned. He outlawed Mosaddegh's political group the National Front, and arrested most of its leaders.[27] Over 4000 political activists of the Tudeh party were arrested,[28] (including 477 in the armed forces), forty were executed, another 14 died under torture and over 200 were sentenced to life imprisonment.[27][29][30]

During the height of its power, the shah's secret police SAVAK had virtually unlimited powers. The agency closely collaborated with the CIA.[31]

According to Amnesty International’s Annual Report for 1974-1975 "the total number of political prisoners has been reported at times throughout the year [1975] to be anything from 25,000 to 100,000."[32]

1971–77

In 1971, a guerrilla attack on a gendarmerie post (where three police were killed and two guerrillas freed, known as the "Siahkal incident") sparked "an intense guerrilla struggle" against the government, and harsh government countermeasures.[33] Guerrillas embracing "armed struggle" to overthrow the Shah, and inspired by international Third World anti-imperialist revolutionaries (Mao Zedong, Ho Chi Minh, and Che Guevara), were quite active in the first half of the 1970s[34][35] when hundreds of them died in clashes with government forces and dozens of Iranians were executed.[36] According to Amnesty International, the Shah carried out at least 300 political executions.[37]

Torture was used to locate arms caches, safe houses and accomplices of the guerrillas, in addition to its possible ability to persuade enemies of the state to become supporters, instead.[38]

In 1975, the human rights group Amnesty International – whose membership and international influence grew greatly during the 1970s[39] – issued a report on treatment of political prisoners in Iran that was "extensively covered in the European and American Press".[40] By 1976, this repression was softened considerably thanks to publicity and scrutiny by "numerous international organizations and foreign newspapers" as well as the newly elected President of the United States, Jimmy Carter.[41][42]

Islamic Revolution

During the 1978–79 overthrow of the Pahlavi government, protestors were fired upon by troops and prisoners were executed. The real and imaginary human rights violations contributed directly to the Shah's demise,[43] (although some have argued so did his scruples in not violating human rights more as urged by his generals[44]).

The 1977 deaths of the popular and influential modernist Islamist leader Ali Shariati and the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's son Mostafa were believed to be assassinations perpetrated by SAVAK by many Iranians.[45][46] On 8 September 1978, (Black Friday) troops fired on religious demonstrators in Zhaleh (or Jaleh) Square. The clerical leadership announced that "thousands have been massacred by Zionist troops" (i.e. rumored Israel troops aiding the Shah),[47] Michel Foucault reported 4000 had been killed,[48] and another European journalist reported that the military left behind a `carnage`.[49]

Post-revolution

The Islamic revolution is thought to have a significantly worse human rights record than the Pahlavi Dynasty it overthrew. According to political historian Ervand Abrahamian, "whereas less than 100 political prisoners had been executed between 1971 and 1979, more than 7900 were executed between 1981 and 1985. ... the prison system was centralized and drastically expanded ... Prison life was drastically worse under the Islamic Republic than under the Pahlavis. One who survived both writes that four months under [warden] Ladjevardi took the toll of four years under SAVAK.[50] In the prison literature of the Pahlavi era, the recurring words had been ‘boredom’ and ‘monotony’. In that of the Islamic Republic, they were ‘fear’, ‘death’, ‘terror’, ‘horror’, and most frequent of all ‘nightmare’ (‘kabos’)."[36]

However, the vast majority of killings of political prisoners occurred in the first decade of the Islamic Republic, after which violent repression lessened.[51] With the rise of the Iranian reform movement and the election of moderate Iranian president Mohammad Khatami in 1997 numerous moves were made to modify the Iranian civil and penal codes in order to improve the human rights situation. The predominantly reformist parliament drafted several bills allowing increased freedom of speech, gender equality, and the banning of torture. These were all dismissed or significantly watered down by the Guardian Council and leading conservative figures in the Iranian government at the time.[52]

According to The Economist magazine:

The Tehran spring of ten years ago has now given way to a bleak political winter. The new government continues to close down newspapers, silence dissenting voices and ban or censor books and websites. The peaceful demonstrations and protests of the Khatami era are no longer tolerated: in January 2007 security forces attacked striking bus drivers in Tehran and arrested hundreds of them. In March police beat hundreds of men and women who had assembled to commemorate International Women's Day.[53]

International criticism

Since the founding of the Islamic Republic, human rights violations of religious minorities have been the subject of resolutions and decisions by the United Nations and its human rights bodies, the Council of Europe, European Parliament and United States Congress.[54] According to The Minority Rights Group, in 1985 Iran became "the fourth country ever in the history of the United Nations" to be placed on the agenda of the General Assembly because of "the severity and the extent of this human rights record".[55] From 1984 to 2001, United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) passed resolutions about human rights violations against Iran's religious minorities especially the Bahá'ís.[54] The UNCHR did not pass such a resolution in 2002, when the government of Iran extended an invitation to the UN "Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression" to visit the country and investigate complaints. However, according to the organization Human Rights Watch, when these officials did visit the country, found human rights conditions wanting and issued reports critical of the Islamic government, not only did the government not implement their recommendations, it retaliated "against witnesses who testified to the experts."[56]

In 2003 the resolutions began again with Canada sponsoring a resolution criticizing Iran's "confirmed instances of torture, stoning as a method of execution and punishment such as flogging and amputations," following the death of an Iranian-born Canadian citizen, Zahra Kazemi, in an Iranian prison.[57][58] The resolution has passed in the UN General Assembly every year since.[57]

The European Union has also criticized the Islamic Republic's human rights record, expressing concern in 2005, 2007[59] and on 6 October 2008 presenting a message to Iran's ambassador in Paris expressing concern over the worsening human rights situation in Iran.[60] On 13 October 2005, the European Parliament voted to adopt a resolution condemning the Islamic government's disregard of the human rights of its citizens. Later that year, Iran's government announced it would suspend dialogue with the European Union concerning human rights in Iran.[61] On 9 February 2010, the European Union and United States issued a joint statement condemning "continuing human rights violations" in Iran.[62]

Late November 2018, a group of UN human rights experts including Javid Rehman U.N. Special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran and four others experts concern about Farhad Meysami’s situation who has been on hunger strike since August.[63]

On 20 December 2018 Human rights Watch urged the regime in Iran to investigate and find an explanation for the death of Vahid Sayadi Nasiri who had been jailed for insulting the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. According to his family Nasiri had been on hunger strike but he was denied medical attention before he died.[64] Amnesty International has reported that more than 7000 people have been arrested by Iran’s security forces in the anti-government demonstrations of 2018.The detainees have been students, workers, human rights activists, . . .[65]

United Nations

On 15 March 2019, 42 human rights organizations, in a statement published in New York, called the United Nations Human Rights Council to extend the mandate of Javid Rahman, the special rapporteur to Iran.[66]

Relative openness

One observation made by non-governmental sources of the state of human rights in the Islamic Republic is that it is not so severe that the Iranian public is afraid to criticize its government publicly to strangers. In Syria "taxi driver[s] rarely talk politics; the Iranian[s] will talk of nothing else."[67]

A theory of why human rights abuses in the Islamic Republic are not as severe as Syria, Afghanistan (under the Taliban), or Iraq (under Saddam Hussein) comes from the American journalist Elaine Sciolino who speculated that

Shiite Islam thrives on debate and discussion ... So freedom of thought and expression is essential to the system, at least within the top circles of religious leadership. And if the mullahs can behave that way among themselves in places like the holy city of Qom, how can the rest of a modern-day society be told it cannot think and explore the world of experience for itself?[68]

Perspective of the Islamic Republic

Iranian officials have not always agreed on the state of human rights in Iran. In April 2004, reformist president Mohammad Khatami stated "we certainly have political prisoners [in Iran] and ... people who are in prison for their ideas." Two days later, however, he was contradicted by Judiciary chief Ayatollah Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi, saying "we have no political prisoners in Iran" because Iranian law does not mention such offenses, ... "The world may consider certain cases, by their nature, political crimes, but because we do not have a law in this regard, these are considered ordinary offenses."[69]

Iran's president President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and other government officials have compared Iran's human rights record favorably to other countries, particularly countries that have criticized Iran's record.[70] In a 2008 speech, he replied to a question about human rights by stating that Iran has fewer prisoners than America and that "the human rights situation in Iran is relatively a good one, when compared ... with some European countries and the United States."[71]

In a 2007 speech to the United Nations, he commented on human rights only to say "certain powers" (unnamed) were guilty of violating it, "setting up secret prisons, abducting persons, trials and secret punishments without any regard to due process, .... "[72] Islamic Republic officials have also attacked Israeli violations of Palestinian human rights.[70]

Constitutional and legal foundations

Explanations for violations

Among the explanations for violations of human rights in the Islamic Republic are:

Theological differences

The legal and governing principles upon which the Islamic Republic of Iran is based differ in some respects from the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- Sharia law, as interpreted in the Islamic Republic, calls for inequality of rights between genders, religions, sexual orientation, as well as for other internationally criticized practices such as stoning as a method of execution.[73] In 1984, Iran's representative to the United Nations, Sai Rajaie-Khorassani, declared the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to be representing a "secular understanding of the Judeo-Christian tradition", which could not be implemented by Muslims and did not "accord with the system of values recognized by the Islamic Republic of Iran" which would "therefore not hesitate to violate its provisions."[74]

- According to scholar Ervand Abrahamian, in the eyes of Iranian officials, "the survival of the Islamic Republic – and therefore of Islam itself – justified the means used," and trumped any right of the individual.[75] In a fatwa issued by Ayatollah Khomeini in early 1988, he declared Iran's Islamic government "a branch of the absolute governance of the Prophet of God" and "among the primary ordinances of Islam," having "precedence over all secondary ordinances such as prayer, fasting, and pilgrimage."[76][77]

Rights under the constitution

The Iranian fundamental law or constitution calls for equal rights among races, ethnic groups (article 19).[78] It calls for gender equality (article 20), and protection of the rights of women (article 21); freedom of expression (article 23); freedom of press and communication (article 24) and freedom of association (article 27). Three recognized religious minorities "are free to perform their religious rites and ceremonies."[79]

However, along with these guarantees the constitution includes what one scholar calls "ominous Catch-22s", such as "All laws and regulations must conform to the principles of Islam."[80] The rights of women, of expression, of communication and association, of the press[81] – are followed by modifiers such as "within the limits of the law", "within the precepts of Islam", "unless they attack the principles of Islam", "unless the Law states otherwise", "as long as it does not interfere with the precepts of Islam."[82]

Provisions in violation of Human Rights

The Iranian penal code is derived from the Shari'a and is not always in compliance with international norms of human rights.

The Iranian penal code distinguishes two types of punishments: Hudud (fixed punishment) and the Qisas (retribution) or Diyya (Blood money or Talion Law). Punishments falling within the category of Hududs are applied to people committing offenses against the State, such as adultery, alcohol consumption, burglary or petty theft, rebellions against Islamic authority, apostasy and homosexual intercourse (considered contrary to the spirit of Islam).[83] Punishments include death by hanging, stoning[84] or decapitation, amputation or flagellation. Victims of private crimes, such as murder or rape, can exercise a right to retribution (Qisas) or decide to accept "blood money" (Diyyah or Talion Law).[85]

Harsh punishments

Following traditional shariah punishment for thieves, courts in Iran have sometimes sentenced offenders to amputation of both "the right hand and left foot cut off, making it difficult, if not impossible, for the condemned to walk, even with a cane or crutches." This was the fate, for example, of five convicted robbers in the Sistan-Baluchistan Province in January 2008 according to the news agency ISNA.[86]

Shariah also includes stoning and explicitly states that stones used must be small enough to not kill instantly.[87][88][89] As of July 2010, the Iranian penal code authorizes stoning as a punishment.[90][91] However, Iran says a new draft of the penal code that has removed stoning is currently under review by the Iranian parliament and has yet to be ratified.[92]

The use of stoning as a punishment may be declining or banned altogether. In December 2002, Ayatollah Shahroudi, head of the judicial system, reportedly sent judges a memorandum requesting the suspension of stoning and asking them to choose other forms of sanctions. In 2005, Amnesty International reported that Iran was about to execute a woman by stoning for adultery. Amnesty urged Tehran to give reprieve to the woman. Her sentence is currently on hold pending "consideration by the pardons commission." According to the Iranian officials "Stoning has been dropped from the penal code for a long time, and in the Islamic Republic, we do not see such punishments being carried out", said judiciary spokesman Jamal Karimirad. He added that if stoning sentences were passed by lower courts, they were overruled by higher courts and "no such verdicts have been carried out."[93] According to Amnesty International, in July 2010, the Iranian parliament began considering a revision to its penal code that would ban stoning as a punishment.[92]

An Iranian MP talks about more executions and more flogging. On 22 December 2018, Aziz Akbarian chairman of the Parliament's Committee on Industries and Mines said in an interview with the local Alborz Radio, "If two people are thoroughly flogged and if two people are executed . . . it will be a lesson for everyone else,"[94]

Gender issues

The Iranian legislation does not accord the same rights to women as to men in all areas of the law.[95]

- In the section of the penal code devoted to blood money, or Diyya, the value of woman's life is half that of a man ("for instance, if a car hit both on the street, the cash compensation due to the woman's family was half that due the man's")[96]

- The testimony of a male witness is equivalent to that of two female witnesses.[95][97][98]

- A woman needs her husband's permission to work outside the home or leave the country.[95]

- Post-pubescent women are required to cover their hair and body in Iran and can be arrested for failing to do so.[99]

In the inheritance law of the Islamic Republic there are several instances where the woman is entitled to half the inheritance of the man.[100] For example:

- If a man dies without offspring, his estate is inherited by his parents. If both the parents are alive, the mother receives 1/3 and the father 2/3 of the inheritance, unless the mother has a hojab (relative who reduces her part, such as brothers and sisters of the deceased (article 886)), in which case she shall receive 1/6, and the father 5/6. (Article 906)

- If the dead man's closest heirs are aunts and uncles, the part of the inheritance belonging to the uncle is twice that belonging to the aunt. (Article 920)[101]

- When the heirs are children, the inheritance of the sons is twice that of the daughters. (Article 907)[101]

- If the deceased leaves ancestors and brothers and sisters (kalaleh), 2/3s of the estate goes to the heirs which have relationship on the side of the father; and in dividing up this portion the males take twice the portion of the females; however, the 1/3 going to the heirs on the mother's side is divided equally. (Article 924)[101]

According to Zahra Eshraghi, granddaughter of Ayatollah Khomeini,

"Discrimination here [in Iran] is not just in the constitution. As a woman, if I want to get a passport to leave the country, have surgery, even to breathe almost, I must have permission from my husband."[102]

Freedom of expression and media

The 1985 press law prohibits "discourse harmful to the principles of Islam" and "public interest", as referred to in Article 24 of the constitution, which according to Human Rights Watch provides "officials with ample opportunity to censor, restrict, and find offense."[81]

Human Rights Watch released a report about Iran's violation of human rights. The Iranian authorities have arrested and detained Shahnaz Karimbeigi whose son, Mostafa, was shot and killed during protests on 27 December 2009, linked to the disputed 2009 presidential election. Accordingly, Karimbeigi participated in many gatherings with the mothers of other victims of the 2009 crackdown to demand justice for their loved ones; she organized public support for the families of imprisoned activists; and she was one of several advocates using social media campaigns to support Arash Sadeghi, a human rights defender sentenced to a 15-year jail term. On the morning of 25 January, she was arrested at her workplace and then denied access to a lawyer. The authorities searched her apartment and seized all her electronic devices, including her laptop as well as threatened Karimbeigi's daughter and husband over the phone and summoned them for several hours of interrogation at the ministry's" Follow-Up Office".[103]

Freedom and equality of religion

The constitution recognizes the freedom of Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian Iranians to perform their religious rites and ceremonies, and accords non-Shia Muslims "full respect" (article 12). However the Bahá'í Faith is banned.[104] The Islamic Republic has stated Baha'is or their leadership are "an organized establishment linked to foreigners, the Zionists in particular," that threaten Iran.[105] The International Federation for Human Rights and others believe the government's policy of persecution of Bahá'ís stems from some Bahá'í teachings challenging traditional Islamic religious doctrines – particularly the finality of Muhammad's prophethood – and place Bahá'ís outside the Islamic faith.[106] Irreligious people are also not recognized and do not have basic rights such as education, becoming member of parliament etc.[107] In 2004, inequality of "blood money" (diyeh) was eliminated, and the amount paid by a perpetrator for the death or wounding a Christian, Jew, or Zoroastrian man, was made the same as that for a Muslim. However, the International Religious Freedom Report reports that Baha'is were not included in the provision and their blood is considered Mobah, (i.e. it can be spilled with impunity).[108]

Freedom to convert from Islam to another religion (apostasy) is prohibited, and may be punishable by death. Article 23 of the constitution states, "the investigation of individuals' beliefs is forbidden, and no one may be molested or taken to task simply for holding a certain belief." But another article, 167, gives judges the discretion "to deliver his judgment on the basis of authoritative Islamic sources and authentic fatwa (rulings issued by qualified clerical jurists)." The founder of the Islamic Republic, Islamic cleric Ruhollah Khomeini, who was a grand Ayatollah, ruled "that the penalty for conversion from Islam, or apostasy, is death."[109]

At least two Iranians – Hashem Aghajari and Hasan Yousefi Eshkevari – have been arrested and charged with apostasy (though not executed), not for converting to another faith but for statements and/or activities deemed by courts of the Islamic Republic to be in violation of Islam, but which appear to outsiders to be simply expressions of political/religious reformism.[110] Hashem Aghajari, was found guilty of apostasy for a speech urging Iranians to "not blindly follow" Islamic clerics;[111] Hassan Youssefi Eshkevari was charged with apostasy for attending the reformist-oriented 'Iran After the Elections' Conference in Berlin Germany which was disrupted by anti-government demonstrators.[112]

The small Protestant Christian minority in Iran have been subject to Islamic "government suspicion and hostility" according to Human Rights Watch at least in part because of their "readiness to accept and even seek out Muslim converts" as well as their Western origins. In the 1990s, two Muslim converts to Christianity who had become ministers were sentenced to death for apostasy and other charges.[113]

Late November, 2018 prison warden Qarchak women prison in Varamin, near the capital Tehran attacked and bit three Dervish religious minority prisoners when they demanded their confiscated belongings back.[114]

Political freedom

In a 2008 report, the organization Human Rights Watch complained that "broadly worded `security laws`" in Iran are used "to arbitrarily suppress and punish individuals for peaceful political expression, association, and assembly, in breach of international human rights treaties to which Iran is party." For example, "connections to foreign institutions, persons, or sources of funding" are enough to bring criminal charges such as "undermining national security" against individuals.[14]

Ahmad Batebi, a demonstrator in the July 1999 Student demonstrations in Iran, was given a death sentence for "propaganda against the Islamic Republic System." (His sentence was later reduced to 15, and then ten years imprisonment.) A photograph of Batebi holding a bloody shirt aloft was printed on the cover of The Economist magazine.

Children's rights

Despite signing the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Iran, according to human rights groups, is the world's largest executioner of juvenile offenders.[115][116][117] As of May 2009, there were at least 137 known juvenile offenders awaiting execution in Iran, but the total number could be much higher as many death penalty cases in Iran are believed to go unreported. Of the 43 child offenders recorded as having been executed since 1990, 11 were still under the age of 18 at the time of their execution while the others were either kept on death row until they had reached 18 or were convicted and sentenced after reaching that age.[118] Including at least one 13-year-old[119] and 14-year-old.[120]

A bill to set the minimum age for the death penalty at 18 years was examined by the parliament in December 2003, but it was not ratified by the Guardian Council of the Constitution, the unelected body that has veto power over parliamentary bills.[121] In a September 2008 interview President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was asked about the execution of minors and replied that "the legal age in Iran is different from yours. It’s not eighteen ... it’s different in different countries."[71]

On 10 February 2012, Iran's parliament changed the controversial law of executing juveniles. In the new law, the age of 18 (solar year) would be for both genders considered and juvenile offenders will be sentenced on a separate law than of adults."[122][123]

In February 2019, a group of United Nations human rights experts condemned the execution of child offenders in Iran. These experts included, Nils Melzer, Special Rapporteur on torture from Switzerland, Agnes Callamard Special Rapporteur on arbitrary executions from France, Renate Winter Rights of the Child from Australia and Javaid Rehman from Pakistan, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran.[124]

Extralegal violations of human rights

.jpg)

A 2005 Human Rights Watch document, criticizes "Parallel Institutions" (nahad-e movazi) in the Islamic Republic, "the quasi-official organs of repression that have become increasingly open in crushing student protests, detaining activists, writers, and journalists in secret prisons, and threatening pro-democracy speakers and audiences at public events." Under the control of the Office of the Supreme Leader, these groups set up arbitrary checkpoints around Tehran, uniformed police often refraining from directly confronting these plainclothes agents. "Illegal prisons, which are outside of the oversight of the National Prisons Office, are sites where political prisoners are abused, intimidated, and tortured with impunity."[125]

According to dissident Akbar Ganji, what might appear to be "extra-legal" killings in Iran are actually not outside the penal code of the Islamic Republic since the code "authorises a citizen to assassinate another if he is judged to be ‘impious’,"[126] Some widely condemned punishments issued by the Islamic Republic – the torture of prisoners and the execution of thousands of political prisoners in 1988 have been reported to follow at least some form of Islamic law and legal procedures, though they have also not been publicly acknowledged by the government.[127]

Extra-legal acts may work in tandem with official actions, such as in the case of the newsweekly Tamadone Hormozgan in Bandar Abbas, where authorities arrested seven journalists in 2007 for "insulting Ayatollah Khomeini," while government organizations and Quranic schools organized vigilantes to "ransacked and set fire" to the paper's offices.[128]

Torture and mistreatment of prisoners

Article 38 of the constitution of the Islamic Republic forbids "all forms of torture for the purpose of extracting confession or acquiring information" and the "compulsion of individuals to testify, confess, or take an oath." It also states that "any testimony, confession, or oath obtained under duress is devoid of value and credence."[129][130]

Nonetheless human rights groups and observers have complained that torture is frequently used on political prisoners in Iran. In a study of torture in Iran published in 1999, Iranian-born political historian Ervand Abrahamian included Iran along with "Stalinist Russia, Maoist China, and early modern Europe" of the Inquisition and witch hunts, as societies that "can be considered to be in a league of their own" in the systematic use of torture.[131]

Torture techniques used in the Islamic Republic include:

whipping, sometimes of the back but most often of the feet with the body tied on an iron bed; the qapani; deprivation of sleep; suspension from ceiling and high walls; twisting of forearms until they broke; crushing of hands and fingers between metal presses; insertion of sharp instruments under the fingernails; cigarette burns; submersion under water; standing in one place for hours on end; mock executions; and physical threats against family members. Of these, the most prevalent was the whipping of soles, obviously because it was explicitly sanctioned by the sharia.[132]

Two "innovations" in torture not borrowed from the Shah's regime were:

the ‘coffin’, and compulsory watching of – and even participation in – executions. Some were placed in small cubicles, [50cm x 80cm x 140cm (20 inches x 31.5 inches x 55 inches)] blindfolded and in absolute silence, for 17-hour stretches with two 15-minute breaks for eating and going to the toilet. These stints could last months – until the prisoner agreed to the interview. Few avoided the interview and also remained sane. Others were forced to join firing squads and remove dead bodies. When they returned to their cells with blood dripping from their hands, Their roommates surmised what had transpired. ....[133]

According to Abrahamian, torture became commonly used in the Islamic Republic because of its effectiveness in inducing political prisoners to make public confessions.[134] Recorded and edited on videotape, the standard statements by prisoners included not only confessions to subversion and treason, but praise of the Islamic Revolution and denunciation or recantation of their former beliefs, former organization, former co-members, i.e. their life. These recantations served as powerful propaganda for both the Iranian public at large – who by the 1980s almost all had access to television and could watch prime time programs devoted to the taped confessions – and the recanters' former colleagues, for whom the denunciations were demoralizing and confusing.[135] From the moment they arrived in prison, through their interrogation prisoners were asked if they were willing to give an "interview." (mosahebah) "Some remained incarcerated even after serving their sentences simply because they declined the honor of being interviewed."[136]

Scholars disagree over whether at least some forms of torture have been made legal according to the Qanon-e Ta'zir (Discretionary Punishment Law) of the Islamic Republic. Abrahamian argues statutes forbidding ‘lying to the authorities’ and ability of clerics to be both interrogators and judges, applying an "indefinite series of 74 lashings until they obtain `honest answers`" without the delay of a trial, make this a legal form of torture.[137] Another scholar, Christoph Werner, claims he could find no Ta'zir law mentioning lying to authorities but did find one specifically banning torture in order to obtain confessions.[138]

Abrahamian also argues that a strong incentive to produce a confession by a defendant (and thus to pressure the defendant to confess) is the Islamic Republic's allowing of a defendant’s confession plus judges "reasoning" to constitute sufficient proof of guilt. He also states this is an innovation from the traditional sharia standard for (some) capital crimes of `two honest and righteous male witnesses`.[139]

Several bills passed the Iranian Parliament that would have had Iran joining the international convention on banning torture in 2003 when reformists controlled Parliament, but were rejected by the Guardian Council.[140][141]

Chronicle of Higher Education International, reports that the widespread practice of raping women imprisoned for engaging in political protest has been effective in keeping female college students "less outspoken and less likely to take part" in political demonstrations. The journal quotes an Iranian college student as saying, "most of the girls arrested are raped in jail. Families can't cope with that."[142]

In 2009, Human Rights charity Freedom from Torture produced a report outlining cases of torture in Iran, including incommunicado detention, blindfolding, and forcing prisoners to sign confessions.[143]

On 28 November 2018 guards in khoy women prison, north west of Iran, attacked inmate Zeynab Jalalian and confiscated all her belongings. She was arrested in February 2007.[144]

On 26 November 2018 Nasrin Sotoudeh, a female political prisoner at Tehran’s Evin Prison started a hunger strike demanding the release of Farhad Meysami a doctor who is in jail for protesting compulsory hijab.[145]

The Iranian Lawyer and human rights activist Amirsalar Davoudi, who is presently jailed at Tehran Evin prison, has been on hunger strike since 9 February 2020. [146]

Davoudi who has defended many Iranian political and religious activists was arrested in November 2018 and was imprisoned on charges of “Propaganda against the state” and “insulting officials”. [147]

Detainees of November Uprising

6 December 2019 - UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet expressed her deep concern about the treatment of the large number of people arrested in recent days demonstrations in Iran. She was also concerned about torture or execution of detainees by Iranian regime.[148]

Death of a juvenile prisoner

Rupert Colville, a spokesman for the United Nations Human Rights Commission, expressed concern about the death of a juvenile prisoner in Iran. Daniel Zeinolabedini, an inmate in the north eastern city of Mahabad, died after he was beaten by prison guards. This happened during the riots in the last days of March 2020, due to spread of coronavirus in Iran. [149]

Notable issues concerning human rights

Extrajudicial killings

In the 1990s there were a number of unsolved murders and disappearances of intellectuals and political activists who had been critical of the Islamic Republic system in some way. In 1998 these complaints came to a head with the killing of three dissident writers (Mohammad Jafar Pouyandeh, Mohammad Mokhtari, Majid Sharif), a political leader (Dariush Forouhar) and his wife in the span of two months, in what became known as the Chain murders or 1998 Serial Murders of Iran.[150][151] of Iranians who had been critical of the Islamic Republic system in some way.[152] Altogether more than 80 writers, translators, poets, political activists, and ordinary citizens are thought to have been killed over the course of several years.[150] The deputy security official of the Ministry of Information, Saeed Emami was arrested for the killings and later committed suicide, many believe higher level officials were responsible for the killings. According to Iranterror.com, "it was widely assumed that [Emami] was murdered in order to prevent the leak of sensitive information about Ministry of Intelligence and Security operations, which would have compromised the entire leadership of the Islamic Republic."[153]

The attempted murder and serious crippling of Saeed Hajjarian, a Ministry of Intelligence operative-turned-journalist and reformer, is believed to be in retaliation for his help in uncovering the chain murders of Iran and his help to the Iranian reform movement in general. Hajjarian was shot in the head by Saeed Asgar, a member of the Basij in March 2000.[154]

At the international level, a German court ordered the arrest of a standing minister of the Islamic Republic – Minister of Intelligence Ali Fallahian – in 1997 for directing the 1992 murder of three Iranian-Kurdish dissidents and their translator at a Berlin restaurant,[155][156] known as the Mykonos restaurant assassinations.

Two minority religious figures killed during this era were Protestant Christians Reverend Mehdi Dibaj, and Bishop Haik Hovsepian Mehr. On 16 January 1994, Rev. Mehdi, a convert to Christianity was released from prison after more than ten years of confinement, "apparently as a result of the international pressure." About six months later he disappeared after leaving a Christian conference in Karaj and his body was found 5 July 1994 in a forest West of Tehran. Six months earlier the man responsible for leading a campaign to free him, Bishop Haik Hovsepian Mehr, had met a similar end, disappearing on 19 January 1994. His body was found in the street in Shahr-e Rey, a Tehran suburb.[113]

Iranian human rights activist Farshid Hakki went missing on 17 October 2018 on Saturday night in Tehran. According to the Le Monde diplomatique, "Farshid Hakki was reportedly stabbed to death near his house in Tehran and his body then burned. Shortly after the news of his death broke out on social media, on 22 October, Tehran’s police authorities claimed that he had committed suicide by self-immolation. Not unlike its Saudi rival, the Islamic Republic has a long history of trying to cover up state-sanctioned attempts to physically eliminate its critics, too."[157]

| Year | Saudi Arabia | Iran |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 27 | 552 |

| 2011 | 82 | 634 |

| 2012 | 79 | 544 |

| 2013 | 79 | 704 |

| 2014 | 90 | 743 |

| 2015 | 158 | 977 |

| 2016 | 154 | 567 |

| 2017 | 146 | 507 |

Capital punishment

Iran retains the death penalty for a large number of offenses, among them cursing the Prophet, certain drug offenses, murder, and certain hadd crimes, including adultery, incest, rape, fornication, drinking alcohol, "sodomy", same-sex sexual conduct between men without penetration, lesbianism, "being at enmity with God" (mohareb), and "corruption on earth" (Mofsed-e-filarz).[162] Drug offenses accounted for 58% of confirmed executions in Iran in 2016, but only 40% in 2017, a decrease that may reflect legislative reforms.[160][161]

Despite being a signatory to the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which states that "[the] sentence of death shall not be imposed for crimes committed by persons below eighteen years of age,"[163] Iran continues to execute minors for various offenses: At least four individuals were executed in Iran in 2017 for offenses committed before the age of eighteen.[161]

Judicial executions in Iran are more common than in any other Middle Eastern state, surpassing Iran's nearest rival—Saudi Arabia—by nearly an order of magnitude according to Michael Rubin in 2017, although Iran's population is over twice as large as Saudi Arabia's.[158][164] In 2017, Iran accounted for 60% of all executions in the Middle East/North Africa while Saudi Arabia accounted for 17% and Iraq accounted for 15%.[161]

In 2014, Atena Daemi was arrested by Iranian authorities for peaceful human rights activism against the government and for criticizing the mass execution of political prisoners. She was jailed for 5 years. According to VOA, the father of Daemi said that new charges have been imposed against her.[165]

1988 massacre of political prisoners

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran and the UN Secretary General to the General Assembly highlighting the 1988 executions of Iranian political prisoners of political prisoners in the Islamic Republic of Iran. In her report, Special Rapporteur Asma Jahangir stated that "families of the victims have the right to a remedy, which includes the right to an effective investigation of the facts and public disclosure of the truth; and the right to reparation. The Special Rapporteur therefore calls on the Government to ensure that a thorough and independent investigation into these events is carried out." International civil society and NGOs urged the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to establish a fact—finding mission to investigate the months-long 1988 massacre during which Iran's government executed an estimated 30,000 political prisoners, mostly activists of the People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI / MEK).[166]

Political freedom

The Islamic government has not hesitated to crush peaceful political demonstrations. The Iran student riots, July 1999 were sparked by an attack by an estimated 400 paramilitary[167] Hezbollah vigilantes on a student dormitory in retaliation for a small, peaceful student demonstration against the closure of the reformist newspaper, Salam earlier that day. "At least 20 people were hospitalized and hundreds were arrested," in the attack.[168][169]

On 8 March 2004, the "parallel institution" of the Basij issued a violent crackdown on the activists celebrating International Women's Day in Tehran.[170]

LGBT issues

Homosexual acts and adultery are criminal and punishable by life imprisonment or death after multiple offenses, and the same sentences apply to convictions for treason and apostasy. Those accused by the state of homosexual acts are routinely flogged and threatened with execution.[171][172][173][174][175][176][177] Iran is one of seven countries in the world that apply the death penalty for homosexual acts; all of them justify this punishment with Islamic law. The Judiciary does not recognize the concept of sexual orientation, and thus from a legal standpoint there are no homosexuals or bisexuals, only persons committing homosexual acts.[178]

For some years after the Iranian Revolution, transgender people were classified by the Judiciary as being homosexual and were thus subject to the same laws. However, in the mid-1980s, the Judiciary began changing this policy and classifying transgender individuals as a distinct group, separate from homosexuals, granting them legal rights. Gender dysphoria is officially recognized in Iran today, and the Judiciary permits sexual reassignment surgery for those who can afford it.[179] In the early 1960s, Ayatollah Khomeini had issued a ruling permitting gender reassignment, which has since been reconfirmed by Ayatollah Khamenei.[180] Currently, Iran has between 15,000 and 20,000 transsexuals, according to official statistics, although unofficial estimates put the figure at up to 150,000. Iran carries out more gender change operations than any country in the world besides Thailand. Sex changes have been legal since the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, spiritual leader of the 1979 Islamic revolution, passed a fatwa authorising them nearly 25 years ago. Whereas homosexuality is considered a sin, transsexuality is categorized as an illness subject to cure. While the government seeks to keep its approval quiet, state support has increased since Ahmadinejad took office in 2005. His government has begun providing grants of £2,250 for operations and further funding for hormone therapy. It is also proposing loans of up to £2,750 to allow those undergoing surgery to start their own businesses.[181]

Gender inequality

Unequal value for women's testimony compared to that of a man,[182] and traditional attitudes towards women's behavior and clothing as a way of explaining rape[183] have made conviction for rape of women difficult if not impossible in Iran. One widely criticized case was that of Atefah Sahaaleh, who was executed by the state for 'inappropriate sexual relations', despite evidence she was most probably a rape victim.[184][185]

Differences in blood money for men and women include victims and offenders. In 2003, the parents of Leila Fathi, an 11-year-old village girl from Sarghez who was raped and murdered, were asked to come up with the equivalent of thousands of US dollars to pay the blood money (diyya) for the execution of their daughter's killers because a woman's life is worth half that of a man's life.[186]

Religious freedom

Bahá'í issues

Amnesty International and others report that 202 Bahá’ís have been killed since the Islamic Revolution,[187] with many more imprisoned, expelled from schools and workplaces, denied various benefits or denied registration for their marriages.[54] Iranian Bahá'ís have also regularly had their homes ransacked or been banned from attending university or holding government jobs, and several hundred have received prison sentences for their religious beliefs, most recently for participating in study circles.[106] Bahá'í cemeteries have been desecrated and property seized and occasionally demolished, including the House of Mírzá Buzurg, Bahá'u'lláh's father.[54] The House of the Báb in Shiraz has been destroyed twice, and is one of three sites to which Bahá'ís perform pilgrimage.[54][188][189]

The Islamic Republic has often stated that arrested Baha'is are being detained for "security issues" and are members of "an organized establishment linked to foreigners, the Zionists in particular."[105] Bani Dugal, the principal representative of the Baha'i International Community to the United Nations, replies that "the best proof" that Bahais are being persecuted for their faith, not for anti-Iranian activity "is the fact that, time and again, Baha'is have been offered their freedom if they recant their Baha'i beliefs and convert to Islam ..."[105]

Jewish issues

Jews have lived in Iran for nearly 3,000 years and Iran is host to the largest Jewish community in the Middle East outside of Israel. An estimated 25,000 Jews remain in the country, although approximately 75% of Iran's Jewish population has emigrated during and since the Islamic revolution of 1979 and Iran-Iraq war[190] In the early days after the Islamic revolution in 1979, several Jews were executed on charges of Zionism and relations with Israel.[191] Jews in Iran have constitutional rights equal to other Iranians, although they may not hold government jobs or become army officers. They have freedom to follow their religion, but are not granted the freedom to proselytize. Despite their small numbers, Jews are allotted one representative in parliament.

Iran's official government-controlled media published the Protocols of the Elders of Zion in 1994 and 1999. Jewish children still attend Jewish schools where Hebrew and religious studies are taught, but Jewish principals have been replaced by Muslim ones, the curricula are government-supervised, and the Jewish Sabbath is no longer recognized.[191] According to Jewish journalist Roger Cohen:

Perhaps I have a bias toward facts over words, but I say the reality of Iranian civility toward Jews tells us more about Iran – its sophistication and culture – than all the inflammatory rhetoric. That may be because I'm a Jew and have seldom been treated with such consistent warmth as in Iran.[192]

Cohen's depiction of Jewish life in Iran sparked criticism from columnists and activists such as Jeffrey Goldberg of The Atlantic Monthly[193] and Rafael Medoff, director of the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies. In his Jerusalem Post op-ed, Medoff criticized Cohen for being "misled by the existence of synagogues" and further argued that Iranian Jews "are captives of the regime, and whatever they say is carefully calibrated not to get themselves into trouble."[194] The American Jewish Committee also criticized Cohen's articles. Dr. Eran Lerman, director of the group's Middle East directory, argued that "Cohen’s need to argue away an unpleasant reality thus gives rise to systematic denial".[195] Cohen responded on 2 March, defending his observations and further elaborating that "Iran’s Islamic Republic is no Third Reich redux. Nor is it a totalitarian state." He also stated that "life is more difficult for them [the Jews] than for Muslims, but to suggest they [Jews] inhabit a totalitarian hell is self-serving nonsense."[196]

Privately, many Jews complain to foreign reporters of "discrimination, much of it of a social or bureaucratic nature." The Islamic government appoints the officials who run Jewish schools, most of these being Muslims and requires that those schools must open on Saturdays, the Jewish Sabbath. (This has apparently been changed as of 4 February 2015.[197]) Criticism of this policy was the downfall of the last remaining newspaper of the Iranian Jewish community which was closed in 1991 after it criticized government control of Jewish schools. Instead of expelling Jews en masse like in Libya, Iraq, Egypt, and Yemen, the Iranians have adopted a policy of keeping Jews in Iran.[198]

Non-government Muslim Shia issues

Muslim clerical opponents of the Islamic Republic's political system have not been spared imprisonment. According to an analyst quoted by Iran Press Service, "hundreds of clerics have been arrested, some defrocked, other left the ranks of the religion on their own, but most of them, including some popular political or intellectual figures such as Hojjatoleslam Abdollah Noori, a former Interior Minister or Hojjatoleslam Yousefi Eshkevari, an intellectual, or Hojjatoleslam Mohsen Kadivar", are "middle rank clerics."[199]

Darvish issues

Iran's Darvish[200] are a persecuted minority. As late as the early 1900s, wandering darvish were a common sight in Iran.[201] They are now much fewer in number and suffer from official opposition to the Sufi religion.

On 16 November 2018 two jailed Sufi Dervishes started a hunger strike demanding the information of whereabouts of their eight [202]

Irreligious people

According to the official Iranian census of 2006, there are 205,317 irreligious people in Iran, including atheists, agnostics, and sceptics.[203] According to the Iranian constitution, an irreligious person can't become president of Iran.

Ethnic minorities

Iran is a signatory to the convention to the elimination of racism. UNHCR found several positive aspects in the conduct of the Islamic republic with regards to ethnic minorities, positively citing its agreement to absorb Afghan refugees and participation from mixed ethnicities. However, the committee while acknowledging that teaching of minority languages and literature in schools is permitted, requested that Iran include more information in its next periodic report concerning the measures it has adopted to enable persons belonging to minorities to have adequate opportunities to learn their mother tongue and to have it used as a medium of instruction.[204]

Workers' Rights

December 2019 - Moghiseh, a notorious clergy judge, sentenced Ali Nejati to five years imprisonment. Mr. Nejati , is a member of workers union at Haft-Tapeh Sugar Mill Company in Khuzistan south of Iran. He was arrested during 2018 protests, held by company’s workers, demanding their unpaid salaries. The government has accused Mr. Nejati as “Assembly and Collusion against national security”. [205]

Legal System

4 March 2020, Javad Soleimani, an Iranian whose wife was among the 175 passengers killed in the downed Ukrainian plane, says agents of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence have told his family not to file any complaint or face consequences as did Pouya Bakhtiari’s father. 27-year-old Pouya was killed in November uprising. Pouya’s parents are now imprisoned. [206] [207]

Current situation

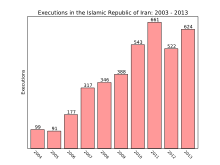

Under the administration of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, beginning in 2005, Iran's human rights record "has deteriorated markedly" according to the group Human Rights Watch. The number of offenders executed increased from 86 in 2005 to 317 in 2007. Months-long arbitrary detentions of "peaceful activists, journalists, students, and human rights defenders" and often charged with "acting against national security," has intensified under President Ahmadinejad[3] In December 2008, the United Nations General Assembly voted to expressed "deep concern" for Iran's human rights record[209] – particularly "cases of torture; the high incidence of executions and juvenile executions ... ; the persecution of women seeking their human rights; discrimination against minorities and attacks on minority groups like the Baha'is in state media ..."[210] Following the protests over the June 2009 presidential elections, dozens were killed,[211][212] hundreds arrested – including dozens of opposition leaders[7][8] – several journalists arrested or beaten, foreign media barred from leaving their offices to report on demonstrations, and Web sites and bloggers threatened.[211] Basij or Revolutionary Guard were reportedly responsible for at least some of the slain protesters.[213]

Freedom of the press

In Freedom House's 2013 press freedom survey, Iran was ranked "Not Free",[214] and among "The world’s eight worst-rated countries" (coming in 5th out of 196).[215][216] According to the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index for 2013, Iran ranked 174th out of 179 nations.[217] According to the International Press Institute and Reporters Without Borders, the government of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and the Supreme National Security Council had imprisoned 50 journalists in 2007 and had all but eliminated press freedom.[218] RWB has dubbed Iran the "Middle East's biggest prison for journalists."[219][220] 85 newspapers, including 41 dailies, were shut down from 2000 to the end of 2002 following the passing of the "April 2000 press law."[221] In 2003, that number was nearly 100.[222] There are currently 45 journalists in prison a number surpassed only by Turkey with 49.[223] The "red lines" of press censorship in Iran are said to be questioning rule by clerics (velayat-e faqih) and direct attacks on the Supreme Leader. Red lines have also drawn against writing that "insults Islam", is "sexually explicit", "politically subversive," or is allegedly "confusing public opinion."[224]

Journalists are frequently warned or summoned if they are perceived as critical of the government, and topics such as U.S. relations and the country's nuclear program are forbidden subjects for reporting.[225][226]

In February 2008, the journalist Yaghoob Mirnehad was sentenced to death on charges of "membership in the terrorist Jundallah group as well as crimes against national security."[227] Mirnehad was executed on 5 July 2008.[228]

In November 2007, freelance journalist Adnan Hassanpour received a death sentence for "undermining national security," "spying," "separatist propaganda" and being a mohareb (fighter against God).[229] He refused to sign a confessions, and it is theorized that he was arrested for his work with US-funded radio stations Radio Farda and Voice of America.[229] Hassanpour's sentence was overturned on 4 September 2008, by the Tehran Supreme Court.[230] Hassanpour still faces espionage charges.[231][232]

In June 2008, the Iranian Ministry of Labor stated that the 4,000 member journalists' union, founded in 1997, was "fit for dissolution."[233]

Human rights blogger and U.S. National Press Club honoree Kouhyar Goudarzi has twice been arrested for his reporting, most recently on 31 July 2011. He is currently in detention, and his whereabouts are unknown.[234] Following his second arrest, Amnesty International named him a prisoner of conscience.[235]

In 2019, Iranian police detained Nicolas Pelham of The Economist for several weeks.[236]

Artistic freedom

In 2003, Iranian expatriate director Babak Payami's film Silence Between Two Thoughts[237] was seized by Iranian authorities, and Payami smuggled a digital copy out of Iran which was subsequently screened in several film festivals.[238]

Arresting musician

Mehdi Rajabian, is an Iranian composer, musician and the founder of the website Barg Music. He was imprisoned for pursuing illegal musical activities in 2013 and 2015. He was arrested by Iranian security forces on 5 October 2013 outside his office in Sari, and was transferred to Ward 2-A of Evin Prison where he was held in solitary confinement for more than two months and were threatened with televised confessions. In 2013, after his first arrestment, all the materials of his album, Barg Music, and his office were all seized. He was released on bail (around $66,000) in mid-December, pending trial. Two years later, his case was heard at Branch 28 of Tehran Revolutionary Court which was presided over by Judge Moghisseh (Summer 2015). He was sentenced to six years in prison and fines for pursuing illegal music activities, launching propaganda against the establishment, cooperating with banned musicians, and hurling insults at sanctities. On appeal, his sentence was changed to three years imprisonment and three years of suspended jail and Fines. He went on hunger strike to protest against unjust trial, and lack of medical facilities. During the first hunger strike period, which lasted 14 days, he could not continue his hunger strike because of the interference of the representative of the prosecutor who was sent as an intermediary. After some time, he sent an open letter to the judicial authorities of Iran, and international artists, and again (with his brother) went on strike. After 36 days of hunger strike, he convinced Iranian judicial authorities to allow him go on a temporary treatment as on bail. As a punishment, he was imprisoned in Evin Section 8, along with Somalian pirates, and Tanzanian and Japanese drug dealers. During his furlough, he published the hand written piece from the pirate's leader, who was his cell mate during his time in prison. He received the Global Investigative Journalism Network's (GIJN) Choice Artist Award in 2017. In Iran he's on no-fly list, and he's banned from education and art related activities.

Arresting filmmakers

_revised.jpg)

On 1 March 2010, Jafar Panahi was arrested. He was taken from his home along with his wife Tahereh Saidi, daughter Solmaz Panahi, and 15 of his friends by plain-clothes officers to Evin Prison. Most were released 48 hours later, Mohammad Rasoulof and Mehdi Pourmoussa on 17 March 2010, but Panahi remained in section 209 inside Evin Prison. Panahi's arrest was confirmed by the government, but the charges were not specified.On 14 April 2010, Iran's Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance said that Panahi was arrested because he "tried to make a documentary about the unrest that followed the disputed 2009 re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad."On 18 May, Panahi sent a message to Abbas Baktiari, director of the Pouya Cultural Center, an Iranian-French cultural organization in Paris, stating that he was being mistreated in prison and his family threatened and as a result had begun a hunger strike. On 25 May, he was released on $200,000 bail while awaiting trial.On 20 December 2010, Panahi, after being convicted for "assembly and colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security and propaganda against the Islamic Republic," the Islamic Revolutionary Court sentenced Panahi to six years imprisonment and a 20-year ban on making or directing any movies, writing screenplays, giving any form of interview with Iranian or foreign media as well as leaving the country except for Hajj holy pilgrimage to Mecca or medical treatment. Panahi's colleague, Mohammad Rasoulof also received six years imprisonment but was later reduced to one year on appeal.On 15 October 2011, a court in Tehran upheld Panahi's sentence and ban. Following the courts decision, Panahi was placed under house arrest. He has since been allowed to move more freely but he cannot travel outside Iran.

Hossein Rajabian, an Iranian independent filmmaker, After finishing his first feature film, was arrested by Iranian security forces on 5 October 2013 outside his office [in Sari] alongside two musicians, and was transferred to Ward 2-A of Evin Prison where all three of them were held in solitary confinement for more than two months and were threatened with televised confessions. He was released on bail (around $66,000) in mid-December, pending trial. Two years later, his case was heard at Branch 28 of Tehran Revolutionary Court which was presided over by Judge Moghisseh (Summer 2015). He was sentenced to six years in prison and fines for pursuing illegal cinematic activities, launching propaganda against the establishment and hurling insults at sanctities. On appeal, his sentence was changed to three years imprisonment and three years of suspended jail and Fines.Hossein Rajabian was sent to the ward 7 of Evin Prison in Tehran. After spending one third of his total period of imprisonment (that is 11 months), he went on hunger strike to protest against unjust trial, lack of medical facilities, and transfer of his brother to another ward called section 8 of the same prison. During the first hunger strike period, which lasted 14 days, he was transferred to hospital because of pulmonary infection and he could not continue his hunger strike because of the interference of the representative of the prosecutor who was sent as an intermediary. After some time, he sent an open letter to the judicial authorities of Iran and went again on strike which brought him the supports of international artists. After 36 days of hunger strike, he could convince the judicial authorities of Iran to review his case and grant him medical leave for the treatment of his left kidney suffered from infections and blood arising out of hunger strike. he, after a contentious struggle with the judicial officer of the prison was sent to the ward 8 for punishment.

Political freedom

Blogger and political activist Samiye Tohidlou was sentenced to 50 lashes for her activities during protests at the 2009 presidential campaign.[239] Activist Peyman Aref was sentenced to 74 lashes for writing an "insulting" open letter to President Ahmadinejad, in which he criticized the president's crackdown on politically active students. An unnamed Iranian journalist based in Tehran commented: "Lashing Aref for insulting Ahmadinejad is shocking and unprecedented."[240]

Freedom of movement

On 8 May 2007, Haleh Esfandiari an Iranian-American scholar in Iran visiting her 93-year-old mother, was detained in Evin Prison and kept in solitary confinement for more than 110 days. She was one of several visiting Iranian-Americans prohibited from leaving Iran in 2007.[241] In December 2008, the presidents of the American National Academy of Sciences issued a warning to "American scientists and academics" against traveling to Iran without "clear assurances" that their personal safety "will be guaranteed and that they will be treated with dignity and respect", after Glenn Schweitzer, who had coordinated the academies’ programs in Iran for the past decade, was detained and interrogated.[242]

Internet freedom

The Internet has grown faster in Iran than any other Middle Eastern country (aside from Israel)[243] since 2000 but the government has censored dozens of websites it considers "non-Islamic" and harassed and imprisoned online journalists.[244] In 2006 and again in 2010, the activist group Reporters Without Borders labeled Iran one of the 12 or 13 countries it designated "Enemies of the Internet" for stepped up efforts to censor the Internet and jail dissidents.[245][246][247] It also ranked worst in "Freedom on the Net 2013 Global Scores".[248] Reporters Without the Borders sent a letter to UN high Commissioner for human rights Navi Pillay to share its deep concern and ask for her intervention in the case of two netizens/free speech defenders, Vahid Asghari and Hossein Derakhshan.[249][250] Reporters Without Borders also believes that it is the Iranian "government’s desire to rid the Iranian Internet of all independent information concerning the political opposition, the women’s movement and human rights”.[251] Where the government cannot legally stop sites it uses advanced blocking software to prevent access to them.[252][253] Many major sites have been blocked entirely such as YouTube,[243][254] IMDB.com,[243] Voice of America,[255] BBC.[255]

According to Amnesty annual report 2015/2016, Iranian authorities continued its policy in restricting freedoms of expression, association and assembly. The report claimed that authorities blocked many of social media websites, including Twitter and Facebook. In June 2015, the authorities have arrested five people for using social media in "anti-revolutionary" activities. In other case, five people were arrested for "acts against decency in internet".[256] On 8 July 2018, Iran has arrested a number of users for posting videos on Instagram, including a young activist named Maedeh Hojabri.[257] As a result, Iranian women posted videos of themselves dancing to protest her arrest.[258]

Deaths in custody

In the past several years many people have died in custody in the Islamic Republic, raising fears that "prisoners in the country are being denied medical treatment, possibly as an extra punishment." Two prisoners who died, allegedly after having "committed suicide" while in jail in northwestern Iran – but whose families reported no signs of behavior consistent with suicidal tendencies – are:

- Zahra Bani Yaghoub, (aka Zahra Bani-Ameri), a 27-year-old female physician died in October 2007, while in custody in the town of Hamedan.

- Ebrahim Lotfallahi, also 27, died in a detention center in the town of Sanandaj in January 2008. "On January 15, officials from the detention center contacted Lotfallahi’s parents and informed them that they had buried their son in a local cemetery."[259]

Political prisoners who recently died in prison under "suspicious circumstances" include:

- Akbar Mohammadi, a student activist, died in Evin prison on 30 July 2006, after waging a hunger strike.[260] Originally sentenced to death for his participation in the pro-democracy July 1999 student riots, his sentence had been reduced to 15 years in prison. "Several sources told Human Rights Watch that after his arrest in 1999, Mohammadi was severely tortured and ill-treated, leading to serious health problems."[261]

- Valiullah Faiz Mahdavi, also died after starting a hunger strike when his appeal for a temporary relief from prison was denied. His cause of death was officially listed as suicide.[260]

- Omid Reza Mir Sayafi, a blogger, died in Evin Prison 18 March 2009, less than six weeks after starting a 30-month sentence.[262]

- Amir Hossein Heshmat Saran, died "in suspicious circumstances" on 6 March 2009, after five years in prison for establishing the United National Front political party.

- Abdolreza Rajabi (1962–2008) was a member of the People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI), who died unexpectedly in Reja'i Shahr Prison on 30 October 2008.[263] He was transferred from Evin to Raja’i Shahr Prison before the news of his death was announced.[260]

Freedom of religion

Bahá'í issues

Around 2005 the situation of Bahá'ís is reported to have worsened;[264] the United Nations Commission on Human Rights revealed an October 2005 confidential letter from Command Headquarters of the Armed Forces of Iran to identify Bahá'ís and to monitor their activities[265] and in November 2005 the state-run and influential Kayhan[266] newspaper, whose managing editor is appointed by Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei,[267] ran nearly three dozen articles defaming the Bahá'í Faith.[268]

Due to these actions, the Special Rapporteur of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights stated on 20 March 2006 that she "also expresses concern that the information gained as a result of such monitoring will be used as a basis for the increased persecution of, and discrimination against, members of the Bahá'í faith, in violation of international standards. … The Special Rapporteur is concerned that this latest development indicates that the situation with regard to religious minorities in Iran is, in fact, deteriorating."[265]

In March and in May 2008, "senior members" forming the leadership of the Bahá'í community in Iran were arrested by officers from the Ministry of Intelligence and taken to Evin prison.[264][269][270] They have not been charged, and they seem to be prisoners of conscience.[271] The Iran Human Rights Documentation Center has stated that they are concerned for the safety of the Bahá'ís, and that the recent events are similar to the disappearance of 25 Bahá'í leaders in the early 1980s.[270]

Muslim Shia issues

One opponent of theocracy, Ayatollah Hossein Kazemeyni Boroujerdi and many of his followers were arrested in Tehran on 8 October 2006. According to mardaninews website, judicial authorities have reportedly released no information concerning Boroujerdi's prosecution and "associates" of Ayatollah Boroujerdi have told the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran "that his heart and kidney conditions are grave but he has had no access to specialist care."

He only receives painkillers for his diseases inside prison. In addition to his physical health, his psychological well-being has also deteriorated due to ill-treatment and lengthy solitary confinement episodes. He has lost 30 kilograms in prison.[272]

Boroujerdi is not the only clergy facing violations in Iran. Ayatullah Shirazi and his followers are continuously arrested, tortured and even killed due to their disapproval of the Iran's policies. Although this family does not openly critique the government, they are the most powerful and internationally known for their freedom of religion for all minorities. Seyed Hussain Shirazi is the last clergy arrested on 6 March 2018 after he advocated for the rights of minorities in his speech.

Ethnic issues

According to Amnesty International's 2007 report, "Ethnic and religious minorities" in the Islamic Republic "remained subject to discriminatory laws and practices which continued to be a source of social and political unrest".[273]

Gender inequality

In 2003, Iran elected not to become a member of the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) since the convention contradicted the Islamic Sharia law in Clause A of its single article.[140]

In a report released 20 October 2008, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called "discriminatory provisions" against women in criminal and civil laws in Iran "in urgent need of reform," and said gender-based violence was "widespread."[274]

Compulsory hijab

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: religious police |

In Spring 2007, Iranian police launched a crackdown against women accused of not covering up enough, arresting hundreds of women, some for wearing too tight an overcoat or letting too much hair peek out from under their veil. The campaign in the streets of major cities is the toughest such crackdown since the Islamic revolution.[275] More than one million Iranians (mostly women) were arrested in a 12-month period (May 2007 – May 2008) for violating the state dress code, according to a May 2008 NBC Today Show report by Matt Lauer.[276]

"Guidance Patrols" (gasht-e ershâd) – often referred to as "religious police" in Western media – enforce Islamic moral values and dress codes. Reformist politicians have criticized the unpopular patrols but the patrols ‘interminable’ according to Iranian judicial authorities who have pointed out that in the Islamic Republic the president does not have control over the enforcement of dress codes.[277]

In May 2016, the Iranian government announced the arrest of eight women involved in online modeling without a mandatory head scarf. Mehdi Abutorabi, a blogger who managed a publishing tool called Persian Blog, was also detained.[278]

Alleged banning of women from universities