Pinellas County, Florida

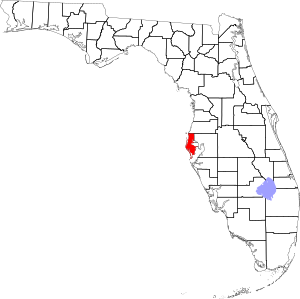

Pinellas County (pih-NEL-ess) is a county located on the west central coast of the state of Florida.[3] As of the 2010 census, the population was 916,542.[4] The county is part of the Tampa–St. Petersburg–Clearwater, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area.[3] Clearwater is the county seat,[5] and St. Petersburg is the largest city and the largest city in Florida that is not a county seat.[3]

Pinellas County | |

|---|---|

| County of Pinellas[1] | |

.jpg) Clearwater Beach | |

Logo | |

Location within the U.S. state of Florida | |

Florida's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 27°54′N 82°44′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | January 1, 1912 |

| Named for | Spanish Punta Piñal ("Point of Pines") |

| Seat | Clearwater |

| Largest city | St. Petersburg |

| Area | |

| • Total | 608 sq mi (1,570 km2) |

| • Land | 274 sq mi (710 km2) |

| • Water | 334 sq mi (870 km2) 55.0%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2019) | 974,996[2] |

| • Density | 3,559/sq mi (1,374/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional districts | 12th, 13th |

| Website | www |

History

Pre-European settlement

When Europeans first reached the Pinellas peninsula, the Tampa Bay area was inhabited by people of the Safety Harbor culture. The Safety Harbor culture area was divided into chiefdoms. One documented chiefdom in what is now Pinellas County was that of the Tocobaga, who occupied a town and large temple mound, the Safety Harbor Site, overlooking the bay in what is now Safety Harbor.[7] The modern site is protected and can be visited as part of the County's Philippe Park.

Spanish and British Florida

During the early 16th century Spanish explorers discovered and slowly began exploring Florida, including Tampa Bay. In 1528 Panfilo de Narvaez landed in Pinellas, and 10 years later Hernando de Soto is thought to have explored the Tampa Bay Area. By the early 18th century the Tocobaga had been virtually annihilated, having fallen victim to European diseases from which they had no immunity, as well as European conflicts. Later Spanish explorers named the area Punta Piñal (Spanish for "Point of Pines" or "Piney Point"). After trading hands multiple times between the British and the Spanish, Spain finally ceded Florida to the United States in 1821, and in 1823 the U.S. Army established Fort Brooke (later Tampa).

Settlement of West Hillsborough

In 1834 much of west central Florida, including the Pinellas peninsula (then known simply as West Hillsborough), was organized as Hillsborough County.[8] The very next year Odet Philippe, a French Huguenot from Charleston, South Carolina became the first permanent, non-native resident of the peninsula when he established a plantation near the site of the Tocobaga village in Safety Harbor. It was Philippe who first introduced both citrus culture and cigar-making to Florida.[9][10][11]

Around the same time, the United States Army began construction of Fort Harrison, named after William Henry Harrison, as a rest post for soldiers from nearby Fort Brooke during the Second Seminole War. The new fort was located on a bluff overlooking Clear Water Harbor, which later became part of an early 20th-century residential development (now historic district) called Harbor Oaks. University of South Florida archaeologists excavated the site in 1977 after Alfred C. Wyllie discovered an underground ammunition bunker while digging a swimming pool on his estate. Clearwater would later become the first organized community on the peninsula as well as the site of its first post office.

The Armed Occupation Act, passed in 1842, encouraged further settlement of Pinellas, like all of Florida, by offering 160 acres (0.65 km2) to anyone who would bear arms and cultivate the land. Pioneer families like the Booths, the Coachmans, the Marstons, and the McMullens established homesteads in the area in the years following, planting more citrus groves and raising cattle. During the American Civil War, many residents fought for the Confederate States of America. Brothers James and Daniel McMullen [12] were members of the Confederate Cow Cavalry, driving Florida cattle to Georgia and the Carolinas to help sustain the war effort. John W. Marston served in the 9th Florida Regiment as a part of the Appomattox Campaign. Many other residents served in other capacities. Otherwise the peninsula had virtually no significance during the war, and the war largely passed the area by.[13]

Tarpon Springs became West Hillsborough's first incorporated city in 1887, and in 1888 the Orange Belt Railway was extended into the southern portion of the peninsula. Railroad owner Peter Demens named the town that grew near the railroad's terminus St. Petersburg in honor of his hometown. The town would incorporate in 1892. Other major towns in the county incorporated during this time were Clearwater (1891), Dunedin (1899), and Largo (1905).

Construction of Fort De Soto, on Mullet Key facing the mouth of Tampa Bay, was begun in 1898 during the Spanish–American War to protect Tampa Bay from potential invading forces. The fort, a subpost of Fort Dade on adjacent Egmont Key (which lies in the mouth of Tampa Bay), was equipped with artillery and mortar batteries.[14]

Birth of Pinellas County

Even into the early years of the 20th century, West Hillsborough had no paved roads, and transportation posed a major challenge. A trip to the county seat, across the bay in Tampa, was generally an overnight affair and the automobiles that existed on the peninsula at that time would frequently become bogged down in the muck after rainstorms. Angry at what was perceived as neglect by the county government, residents of Pinellas began a push to secede from Hillsborough. They succeeded, and on January 1, 1912 Pinellas County came into being.[15][16] The peninsula, along with a small part of the mainland were incorporated into the new county.

Land boom and prohibition

Aviation history was made in St. Petersburg on January 1, 1914 when Tony Jannus made the world's first scheduled commercial airline flight with the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line from St. Petersburg to Tampa. The popular open-air St. Petersburg concert venue Jannus Live (formerly known as "Jannus Landing") memorializes the flight.

The early 1920s saw the beginning of a land boom in much of Florida, including Pinellas. During this period municipalities issued a large number of bonds to keep pace with the needed infrastructure, such as roads and bridges. The travel time to Tampa was cut in half—from 43 to 19 miles (69 to 31 km)—by the opening of the Gandy Bridge in 1924, along the same route Jannus' airline used. It was the longest automobile toll bridge in the world at the time.

Prohibition was unpopular in the area and the peninsula's countless inlets and islands became havens for rumrunners bringing in liquor from Cuba. Others distilled moonshine in the County's still plentiful woods.[17]

Great Depression and World War II

As was the case in much of Florida, the Great Depression came early to Pinellas with the collapse of the real estate boom in 1926. Local economies came into severe difficulties, and by 1930, St. Petersburg defaulted on its bonds. Only after World War II would significant growth return to the area. During the war, the area's tourist industry collapsed, but thousands of recruits came to the area when the U.S. military decided to use the area for training. Area hotels became barracks. The Vinoy Park Hotel was used as an Army training school. The area's women and girls participated in the war effort as well. Hundreds of girls from the area's most prominent families formed a group called the Bomb-a-Dears, holding dances, socializing with recruits, and selling war bonds.[18] After the war many of these same soldiers remembered their wartime experience in Pinellas well, and returned as tourists or residents.

Recent history

With the end of the Second World War, Pinellas would enter another period of rapid growth and development. In 1954 the original span of the Sunshine Skyway Bridge was opened, replacing earlier ferry service. By 1957 Clearwater was America's fastest growing city.

The Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council was founded by the late mayor of St. Petersburg, Herman Goldner, who sought without success during the 1960s to consolidate various municipalities and unincorporated areas in south Pinellas County. Each year the council presents its Herman Goldner Award for Regional Leadership.[19]

Tragedy struck on May 9, 1980, when the southbound span of the original Sunshine Skyway Bridge was struck by the freighter MV Summit Venture during a storm, sending over 1,200 feet (370 m) of the bridge plummeting into Tampa Bay. The collision caused ten cars and a Trailways bus to fall 150 feet (46 m) into the water, killing 35 people.[20][21] The new bridge opened in 1987 and has since been listed as #3 of the "Top 10 Bridges" in the World by the Travel Channel.[22]

The county operates a 21-acre (8.5 ha) living history museum called Heritage Village containing more than 28 historic structures, some dating back to the 19th century, where visitors can experience what life was once like in Pinellas.

Pinellas County celebrated 100 years of existence on January 1, 2012.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 608 square miles (1,570 km2), of which 274 square miles (710 km2) is land and 334 square miles (870 km2) (55.0%) is water.[23] It is the second-smallest county in Florida by land area, larger than only Union County. Pinellas forms a peninsula bounded on the west by the Gulf of Mexico and on the south and east by Tampa Bay. It is 38 miles (61 km) long and 15 miles (24 km) wide at its broadest point, with 587 miles (945 km) of coastline.[24]

Physical geography

.jpg)

Elevation in the county ranges from mean sea level to its highest natural point of 110 feet (34 m) near the intersection of SR 580 and Countryside Blvd. in Clearwater.[25] Due to its small size and high population, by the early 21st century Pinellas County has been mostly built out, with very little developable land left available. The county has maintained a fairly large system of parks and preserves that provide residents and visitors retreat from the city and a glimpse of the peninsula's original state.

Geologically, Pinellas is underlain by a series of limestone formations, the Hawthorne limestone and the Tampa limestone. The limestone is porous and stores a large quantity of water. The Hawthorne formation forms a prominent ridge down the spine of the county, from east of Dunedin, south to the Walsingham area and east towards St. Petersburg.[26]

The 35 miles of beaches and dunes which make up the county's 11 barrier islands provide habitat for coastal species, serve as critical storm protection for the inland communities, and form the basis of the area's thriving tourism industry. The islands are dynamic, with wave action building some islands further up, eroding others, and forming entirely new islands over time. Though hurricanes are infrequent on this part of Florida's coast, they have had a major impact on the islands, with the Hurricane of 1848 forming John's Pass between Madeira Beach and Treasure Island, a hurricane in 1921 creating Hurricane Pass and cleaving Hog Island into Honeymoon and Caladesi Islands, and 1985's Hurricane Elena sealing Dunedin Pass to join Caladesi with Clearwater Beach.[27]

Between the barrier islands and the peninsula are several bodies of water, through which traverses a section of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway. From north to south they are: St. Joseph Sound between the islands and Dunedin, Clearwater Harbor between Clearwater and Clearwater Beach, and Boca Ciega Bay in the southern third of the county. Connecting Clearwater Harbor to Boca Ciega Bay is a thin, approximately 3.5-mile (5.6 km) stretch of water known as The Narrows, which runs next to the town of Indian Shores.

Extending from northeastern Boca Ciega Bay, Long Bayou separates Seminole from St. Petersburg near Bay Pines. Long Bayou once extended significantly farther up the peninsula until the northern portion was sealed off to create Lake Seminole. Extending further still from Long Bayou, the Cross Bayou Canal traverses the peninsula, crossing Pinellas Park in a northeasterly direction before emptying into Tampa Bay on the northwest side of St. Petersburg-Clearwater International Airport.

Barrier islands and passes

- Anclote Key- offshore of Tarpon Springs and the northernmost point in the county

- Howard Park- a man-made pocket beach created in the 1960s

- Three Rooker Bar- the most geologically recent of Pinellas' barrier islands

- Honeymoon Island

- Hurricane Pass

- Caladesi Island

- Dunedin Pass- shoaled and closed in the 1980s, linking Caladesi Island and Clearwater Beach

- Clearwater Beach

- Clearwater Pass

- Sand Key- the longest of Pinellas' barrier islands

- John's Pass

- Treasure Island

- Blind Pass

- Long Key (St. Pete Beach)

- Pass-a-Grille Channel

- Shell Key

- Tierra Verde- on the bay side of Shell Key, links the mainland to Fort De Soto. Created by a dredge-and-fill project that merged several smaller Keys, including Cabbage and Pine Keys

- Bunces Pass

- Mullet Key- home to Fort De Soto and the southernmost point in the county

National protected area

State protected areas

County parks and preserves

|

|

Pinellas County parks gallery

Anderson Park Panorama

Anderson Park Panorama Brooker Creek Nature Preserve walkway

Brooker Creek Nature Preserve walkway View of Lake Tarpon from John Chestnut Park

View of Lake Tarpon from John Chestnut Park Wall Springs View of St Joseph Sound from the old observation tower

Wall Springs View of St Joseph Sound from the old observation tower Sunset at Fred Howard Park

Sunset at Fred Howard Park

Other protected areas

Boyd Hill Nature Preserve- A 245-acre park on the shores of Lake Maggiore in south St. Petersburg, operated by the city and featuring a nature center, bird-of-prey aviary, and over three miles of trails through a variety of ecosystems.[29]

Adjacent counties

- Pasco County — north

- Hillsborough County — east and south

Hillsborough County extends along the shipping channel into the Gulf of Mexico and actually separates Pinellas County from Manatee County.

Ecosystems

Plant life

Several natural communities exist within the county, including areas of freshwater wetlands (dominated by bald cypresses and ferns), coastal mangrove swamps, sporadic hardwood hammocks (dominated by laurel oaks and live oaks, cabbage palms, and southern magnolias), low-lying, poorly drained pine flatwoods (dominated by longleaf pines and saw palmettos), and well-drained, upland sandhills (dominated by longleaf pines and turkey oaks) and sand pine scrub (dominated by sand pines, saw palmettos, and various oaks). Offshore ecosystems include the Tampa Bay estuary and numerous gulf seagrass beds. The county also maintains several artificial reefs

Animal life

Numerous bird species can be sighted in Pinellas, either as permanent residents or during the winter migration, including wading birds like great blue herons, egrets, white ibises and roseate spoonbills, aquatic birds like brown pelicans, white pelicans, and cormorants, numerous species of shorebirds, and very-common birds like seagulls and passerines like the blue jay, mockingbird, and crow. Ospreys are a commonly seen bird-of-prey, with other birds of prey like turkey vultures, red tailed hawks, great horned owls, screech owls, barn owls, and bald eagles, among others, seen as well.

Gopher tortoises are found in many areas, the burrows they dig making them a keystone species. Coyotes, though often associated with the American West, are native-to and can be found in Pinellas. White-tailed deer, wild turkeys, bobcats, otters, and alligators can be found in the county as well.

Sea turtles nest on the shores or Pinellas' barrier islands and have been threatened by development. Offshore, dolphins, sharks, and manatees are numerous as well, while closer inshore stingrays are a common sight, leading those in-the-know to do the "stingray shuffle" (shuffling up the sand to scare nearby stingrays off) when entering gulf waters. Species of fish commonly caught in the waters surrounding the county include spotted seatrout, red drum or redfish, snook, pompano, sheepshead, Spanish mackerel, grouper, mullet, flounder, kingfish, and tarpon.

Invasive species

Like much of Florida, Pinellas County is home to several invasive species that propagate easily outside their (and their natural predators') native range. Examples of commonly seen invasives include Brazilian pepper, water hyacinth, Australian pine, melaleuca and air potato. These species are considered serious pests, and varying methods have been tried to eradicate them. Examples of invasive animals include the wild boar, which poses significant health and agricultural problems in Florida and can sometimes be found in Pinellas, and the monk parakeet, small flocks of which can sometimes be seen in flight or building nests on electrical poles or telecommunications towers.[30]

Pinellas gained some national attention as the home of the Mystery Monkey of Tampa Bay, a non-native, feral rhesus macaque that had been on the loose for approximately three years in the south of the county. No one was sure where the monkey came from, and a Facebook page set up for the monkey had over 84,000 likes (as of October 2012). The monkey was the subject of a sketch on the March 11, 2010 episode of the Colbert Report. As of February 2012, the monkey had apparently taken up semi-permanent residence behind a family's home at an undisclosed location in St. Petersburg, according to the Tampa Bay Times.[31] Efforts to capture the monkey were reignited after it reportedly bit a woman living near where it had taken up residence, and the monkey was captured in late October 2012 and eventually was sent to live at Dade City's Wild Things, a 22-acre (8.9 ha) zoo north of Tampa.

Climate

Pinellas, like the rest of the Tampa Bay area, has a humid subtropical climate, resulting in warm, humid summers with frequent thunderstorms, and drier winters. Pinellas County's geographic position- lying on a peninsula between Tampa Bay and the Gulf of Mexico introduces large amounts of humidity into the atmosphere and serves to moderate temperatures. The geography of the peninsula also causes some variance in the county's average temperatures. St. Petersburg, further south on the peninsula, tends to have warmer daily average lows (by about 3 degrees) than areas such as Dunedin and Palm Harbor further north, though daily highs are very close. The north of the county also has fewer overall days of rain, but higher total annual precipitation when measured in inches, the county's south being prone to shorter, more frequent thunderstorms especially in the late summer.

Freezing temperatures occur only every 2–3 years, with freezing precipitation occurring extremely rarely. Springs are usually short, mild, and dry, with occasional late-season cold fronts. Summertime weather is very consistent, with highs in the low 90s °F (around 32 °C), lows in the mid-70s °F (around 24 °C), accompanied by high humidity and an almost daily chance of afternoon thundershowers. The area experiences significant rainfall during its summer months (approximately May through October), with nearly two-thirds of annual precipitation falling between the months of June and September. The area is occasionally affected by tropical storms and hurricanes, but has not suffered a direct hit since 1921. Fall, like spring, is usually mild and dry, with the hurricane season extending through November and sometimes affecting the area.

Many portions of south Pinellas, especially near the bay and gulf, have tropical microclimates. Tropical trees such as coconut palms and royal palms and fruit trees like mangoes grow very well in these microclimates.

| Climate data for St. Petersburg, Florida | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 69.3 (20.7) |

70.7 (21.5) |

75.2 (24.0) |

80 (27) |

85.8 (29.9) |

89.2 (31.8) |

90.2 (32.3) |

89.9 (32.2) |

88.2 (31.2) |

83 (28) |

76.6 (24.8) |

71.1 (21.7) |

80.8 (27.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 54 (12) |

55.2 (12.9) |

59.7 (15.4) |

64.6 (18.1) |

70.8 (21.6) |

75.2 (24.0) |

76.6 (24.8) |

76.8 (24.9) |

75.8 (24.3) |

70 (21) |

62.9 (17.2) |

56.3 (13.5) |

66.5 (19.2) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 2.76 (70) |

2.87 (73) |

3.29 (84) |

1.92 (49) |

2.80 (71) |

6.09 (155) |

6.72 (171) |

8.26 (210) |

7.59 (193) |

2.64 (67) |

2.04 (52) |

2.60 (66) |

49.58 (1,259) |

| Average rainy days | 6.3 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 4.2 | 5 | 10.3 | 13.5 | 14.2 | 12 | 5.9 | 5 | 5.5 | 94.1 |

| Source: NOAA[32] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Dunedin, Florida | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 69 (21) |

72 (22) |

75 (24) |

80 (27) |

85 (29) |

89 (32) |

90 (32) |

90 (32) |

88 (31) |

83 (28) |

77 (25) |

71 (22) |

80.75 (27.08) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 50 (10) |

53 (12) |

57 (14) |

62 (17) |

68 (20) |

73 (23) |

75 (24) |

75 (24) |

72 (22) |

66 (19) |

59 (15) |

53 (12) |

63.58 (17.54) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 2.99 (76) |

3.05 (77) |

3.81 (97) |

2.37 (60) |

2.02 (51) |

6.69 (170) |

8.09 (205) |

8.32 (211) |

6.99 (178) |

3.31 (84) |

2.15 (55) |

2.95 (75) |

52.74 (1,340) |

| Average rainy days | 4.3 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 9.6 | 11 | 11.6 | 8.3 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 71.1 |

| Source: Weather Channel[33] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1920 | 28,265 | — | |

| 1930 | 62,149 | 119.9% | |

| 1940 | 91,852 | 47.8% | |

| 1950 | 159,249 | 73.4% | |

| 1960 | 374,665 | 135.3% | |

| 1970 | 522,329 | 39.4% | |

| 1980 | 728,531 | 39.5% | |

| 1990 | 851,659 | 16.9% | |

| 2000 | 921,482 | 8.2% | |

| 2010 | 916,542 | −0.5% | |

| Est. 2019 | 974,996 | [34] | 6.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[35] 1790-1960[36] 1900-1990[37] 1990-2000[38] 2010-2019[4] | |||

2010 Census

U.S. Census Bureau 2010 Ethnic/Race Demographics:[39][40]

- White (non-Hispanic) (82.1% when including White Hispanics): 76.9% (17.7% German, 15.5% Irish, 12.6% English, 8.9% Italian, 4.3% Polish, 4.0% French, 2.6% Scottish, 1.9% Scotch-Irish, 1.7% Dutch, 1.4% Swedish, 1.4% Greek, 1.1% Russian, 1.0% French Canadian, 0.9% Norwegian, 0.8% Welsh, 0.8% Hungarian, 0.5% Czech, 0.5% Portuguese, 0.5% Ukrainian)[39]

- Black or African-American (non-Hispanic) (10.3% when including Black Hispanics): 10.0% (0.6% Subsaharan African, 0.5% West Indian/Afro-Caribbean American [0.2% Jamaican, 0.1% Haitian, 0.1% Trinidadian and Tobagonian, 0.1% Other or Unspecified West Indian])[39][41]

- Hispanic or Latino of any race: 8.0% (2.4% Puerto Rican, 2.4% Mexican, 0.9% Cuban)[39][42]

- Asian: 3.0% (0.8% Vietnamese, 0.7% Other Asian, 0.6% Indian, 0.5% Filipino, 0.3% Chinese, 0.1% Korean, 0.1% Japanese)[39][40]

- Two or more races: 2.2%

- American Indian and Alaska Native: 0.3%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.1%[39][40]

- Other Races: 2.0% (0.6% Arab)[39]

In 2010, 6.5% of the population considered themselves to be of only "American" ancestry (regardless of race or ethnicity.)[39]

There were 415,876 households, out of which 19.89% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.33% were married couples living together, 11.86% had a female householder with no husband present, and 43.67% were non-families. 35.42% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.14% (4.53% male and 10.61% female) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.16 and the average family size was 2.79.[40][43]

The age distribution is 17.8% under the age of 18, 7.3% from 18 to 24, 23.0% from 25 to 44, 30.8% from 45 to 64, and 21.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 46.3 years. For every 100 females there were 92.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.8 males.[43]

The median income for a household in the county was $45,258, and the median income for a family was $58,335. Males had a median income of $41,537 versus $35,003 for females. The per capita income for the county was $28,742. About 8.1% of families and 12.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.7% of those under age 18 and 9.0% of those aged 65 or over.[44]

In 2010, 11.2% of the county's population was foreign born, with 50.3% being naturalized American citizens. Of foreign-born residents, 33.6% were born in Europe, 32.1% were born in Latin America, 20.9% born in Asia, 9.8% in North America, 3.0% born in Africa, and 0.6% were born in Oceania.[39]

2000 Census

As of 2000, there were 921,482 people, 414,968 households, and 243,171 families residing in the county. The population density was 1,271/km2 (3,292/sq mi), making it the most densely populated county in Florida. There were 481,573 housing units at an average density of 1,720 per square mile (664/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 85.85% White (82.8% were Non-Hispanic White,)[45] 8.96% Black or African American, 0.30% Native American, 2.06% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 1.14% from other races, and 1.64% from two or more races. 4.64% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 414,968 households, out of which 22.10% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.80% were married couples living together, 10.50% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.40% were non-families. 34.10% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.50% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.17 and the average family size was 2.77.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 19.30% under the age of 18, 6.40% from 18 to 24, 27.30% from 25 to 44, 24.50% from 45 to 64, and 22.50% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43 years. For every 100 females there were 91.00 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.80 males.

In 2000, 87.8% of persons age 25 or above were high school graduates, slightly above Florida's average of 84.9% for Florida. 26.7% of persons age 25 or above held a Bachelor's degree or higher, also slightly higher than Florida's rate of 25.6%.[2]

The median income for a household in the county was $37,111, and the median income for a family was $46,925. Males had a median income of $32,264 versus $26,281 for females. The per capita income for the county was $23,497. About 6.70% of families and 10.00% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.90% of those under age 18 and 8.20% of those age 65 or over.

In 2000, as Florida's 6th and the nation's 53rd most populous county, Pinellas has a population greater than that of the individual states of Wyoming, Montana, Delaware, South Dakota, Alaska, North Dakota, and Vermont, as well as the District of Columbia. With a population density (as of the 2000 Census) of 3292 inhabitants/mi2, Pinellas County is by far the most densely populated county in the state, more than double that of Broward County, the next most densely populated.[46]

Languages

As of 2010, 87.17% of all residents spoke English as their first language, while 5.56% spoke Spanish, 0.78% Vietnamese, 0.70% French, 0.65% Greek, 0.56% German, and 0.52% of the population spoke Serbo-Croatian as their mother language.[47] In total, 12.83% of the population spoke languages other than English as their primary language.[47]

Government and politics

The Board of County Commissioners governs all unincorporated areas of the county under the state's constitution, with the power to adopt ordinances, approve the county budget, set millages, and provide services. The county's municipalities, while governing their own affairs, may call upon the county for specialized services.[48] The county administrator, appointed by and reporting to the Board, oversees most of the day-to-day operations of the county.[49]

As of 2013, The members of the Board of County Commissioners are as follows:

- Janet Long - At-Large District #1 (2012–present)

- Pat Gerard - At-Large District #2 (2014–present)

- Charlie Justice - At-Large District #3 (2012–present)

- Dave Eggers, Single-Member District #4 (2014–present)

- Karen Seel, Single-Member District #5 (1999–present)

- John Morroni - Single-Member District #6 (2000–2018)

- Ken Welch - Single-Member District #7 (2000–present)

- Mark Woodard - County Administrator (2014–present)

The county's government website won a "Sunny Award" in 2010 for its proactive disclosure of government data from Sunshine Review.[50]

In national politics, Pinellas County, as part of the I-4 Corridor stretching from Tampa Bay to Orlando, was one of the first areas of Florida to turn Republican. From 1948 to 1988, it went Republican in every presidential election except Lyndon Johnson's 44-state landslide of 1964. However, for the last quarter-century, it has been a powerful swing county in one of the nation's most critical swing states. Voter registration is almost tied, with Democrats having a small plurality of registered voters. It is closely divided between predominantly liberal St. Petersburg and its predominantly suburban and conservative north and beaches. Due in part to the more populated southern portion around St. Petersburg, it has supported a Democrat for president in all but two elections since 1992. The brand of Republicanism in Pinellas County has traditionally been a moderate one, so the county has become friendlier to Democrats as a result of the national GOP shifted right.[51]

In 2000, Al Gore became the first Democrat to win a majority of the county's vote since 1964, and only the second since Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 2004, Pinellas swing the other way when George W. Bush carried the county by a narrow plurality of 49.56% (225,686 votes), with John Kerry following closely behind with 49.51% (225,460 votes)–a margin of just 226 votes. In the 2012 Presidential Election, Barack Obama won Pinellas with 52% of the vote (239,104 votes) to Mitt Romney's 46.5% (213,258 votes), slightly narrower than Obama’s 2008 election results in Pinellas of 53% (248,299 votes) to John McCain’s 45% (210,066 votes).[52]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 48.08% 239,201 | 46.98% 233,701 | 4.94% 24,583 |

| 2012 | 46.45% 213,258 | 52.08% 239,104 | 1.47% 6,750 |

| 2008 | 45.16% 210,066 | 53.38% 248,299 | 1.46% 6,787 |

| 2004 | 49.56% 225,686 | 49.51% 225,460 | 0.92% 4,211 |

| 2000 | 46.38% 184,849 | 50.35% 200,657 | 3.27% 13,020 |

| 1996 | 40.44% 152,155 | 49.10% 184,748 | 10.46% 39,369 |

| 1992 | 37.63% 159,121 | 37.96% 160,528 | 24.41% 103,202 |

| 1988 | 57.76% 211,049 | 41.72% 152,420 | 0.52% 1,901 |

| 1984 | 65.16% 240,612 | 34.82% 128,574 | 0.02% 63 |

| 1980 | 53.83% 185,728 | 40.12% 138,428 | 6.04% 20,847 |

| 1976 | 50.75% 150,003 | 48.00% 141,879 | 1.25% 3,687 |

| 1972 | 69.83% 179,541 | 30.02% 77,197 | 0.15% 378 |

| 1968 | 51.71% 109,235 | 32.29% 68,209 | 16.01% 33,814 |

| 1964 | 44.98% 80,414 | 55.02% 98,381 | |

| 1960 | 63.68% 101,779 | 36.32% 58,054 | |

| 1956 | 72.55% 74,314 | 27.45% 28,113 | |

| 1952 | 71.35% 55,691 | 28.65% 22,365 | |

| 1948 | 55.92% 24,900 | 35.32% 15,724 | 8.76% 3,900 |

| 1944 | 42.28% 14,340 | 57.72% 19,574 | |

| 1940 | 41.30% 13,327 | 58.70% 18,941 | |

| 1936 | 40.40% 8,183 | 59.60% 12,072 | |

| 1932 | 42.07% 7,024 | 57.93% 9,670 | |

| 1928 | 74.52% 10,545 | 24.30% 3,439 | 1.18% 167 |

| 1924 | 47.53% 2,872 | 43.57% 2,633 | 8.91% 538 |

| 1920 | 43.46% 2,529 | 48.94% 2,848 | 7.60% 442 |

| 1916 | 22.86% 555 | 61.90% 1,503 | 15.24% 370 |

| 1912 | 6.14% 87 | 60.16% 853 | 33.71% 478 |

In the 2012 U.S. Senate election, Pinellas voters helped re-elect U.S. Senator Bill Nelson over challenger Connie Mack IV with 59% of the vote, greater than his statewide average of 55%. In the 2010 U.S. Senate election, Pinellas was one of only four Florida counties won by outgoing Republican Governor Charlie Crist, a St. Petersburg native, who won 42% of Pinellas voters running as an Independent in a three-way race with Republican nominee (and eventual winner) Marco Rubio and former Democratic U.S. Representative Kendrick Meek, who won 37% and 16.8% of the Pinellas vote, respectively. Statewide, Rubio won almost 49% of the vote to Crist's 29.7% and Meek's 20%[54] in a highly polarized election that would witness Crist depart from the Republican Party and eventually become a Democrat.[55]

Portions of Pinellas fall into Florida's 12th and 13th congressional districts, served by Republican Gus Bilirakis and Democrat Crist. A court-ordered remap merged most of the 14th's share of Pinellas into the 13th, enabling Crist to defeat Republican incumbent David Jolly in the 2016 election, breaking a 62-year GOP hold on what is now the 13th.

In state politics, portions of Pinellas are represented in the Florida Senate by Democratic State Senator Arthenia Joyner (District 19) and Republican State Senators Jack Latvala (District 20) and Jeff Brandes (District 22). In the Florida House parts of the county are represented by Republicans James Grant (District 64), Chris Sprowls (District 65), Larry Ahern (District 66), Chris Latvala (District 67), and Kathleen Peters (District 69) and Democrats Dwight Dudley (District 68) and Darryl Rouson (District 70).

Voter registration

| Party | Number of Voters | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | 239,679 | 34.9 | |

| Democratic | 246,030 | 35.8 | |

| Other | 201,017 | 29.3 | |

| Total | 686,726 | 100% | |

Education

Primary and secondary education

The county is served by the Pinellas County School District. The current superintendent is Dr. Michael Grego. The district, the nation's 24th largest, comprises 143 schools, including 72 elementary schools, 18 middle schools, 2 K-8 schools, 17 high schools, and 35 additional facilities including ESE, adult ed, career/technical, and charters. The district also operates the K-12 Pinellas Virtual School. Among the many notable magnet programs in the district are three International Baccalaureate (IB) programs, at St. Petersburg High School, Palm Harbor University High School, and Largo High School, the Center for Advanced Technologies (CAT) at Lakewood High School, the Pinellas County Center for the Arts (PCCA) at Gibbs High School, three middle school Centers for Gifted Studies, at Thurgood Marshall Fundamental, Morgan Fitzgerald, and Dunedin Highland Middle Schools, and Florida's only Fundamental High School, at Osceola High School. Two of the district's high schools are also ranked in Newsweek's 2012 list of America's Best High Schools.[57]

Pinellas County Schools also offers many courses for academically advanced and gifted individuals.

The county is also home to many private schools, including Admiral Farragut Academy, Canterbury School, Calvary Christian, Clearwater Central Catholic, Keswick Christian School, Shorecrest Preparatory School, and St. Petersburg Catholic High School, among others.

Colleges and universities

Pinellas County is home several institutions of higher learning, including Eckerd College, the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, the multi-campus St. Petersburg College, the Stetson University College of Law in Gulfport, and the main campus of Schiller International University in Largo,[58] after previously being located in Dunedin.[59]

Libraries

The Pinellas Public Library Cooperative (PPLC) serves county residents by coordinating activities, funding and information and facilitating borrowing across 15 its constituent systems within the county. Individual libraries are primarily funded and operated by their municipalities. PPLC provides digital resources, coordinated marketing, courier service between libraries, and a shared online publicly accessible catalog.[60]

The PPLC was created in 1989 to provide access to unincorporated areas of Pinellas County and to municipalities that do not have library services.[61] In March of that year, county residents voted to pay an extra tax to allow them to use city libraries throughout the county.[62] The exceptions to this were the cities of Clearwater, South Pasadena, Kenneth City, Indian Rocks, and Indian Shores, who would have to pay a $100 non-member fee to use the PPLC libraries. Clearwater and others have since joined the cooperative. Librarian Bernadette Storck was hired as the cooperative administrator. Storck was retiring from thirty years working in the Tampa-Hillsborough library System. The cooperative opened on Monday, October 1, 1990 with twelve participating libraries across the county.[63] The Pinellas Public Library Cooperative's vision is "to connect communities." [61]

The 14 independent library systems that make up the cooperative are as follows:[64]

- Clearwater Public Library System

- Dunedin Public Library

- East Lake Community Library

- Gulf Beaches Public Library

- Gulfport Public Library

- Largo Public Library

- Oldsmar Public Library

- Palm Harbor Library

- Barbara S. Ponce Public Library

- Safety Harbor Public Library

- St. Petersburg Library System

- St. Pete Beach Public Library

- Seminole Community Library

- Tarpon Springs Public Library

The PPLC website provides information about all programs offered in each of the member libraries monthly.[65]

Due to community partnerships, PPLC offers free admission to the following museums: Museum of Fine Arts, Florida Holocaust Museum, Great Explorations Children's Museum, Henry B. Plant Museum, Imagine Museum, Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art, Dunedin History Museum, and the Tampa Bay History Center.[66]

The PPLC also offers the Pinellas County Talking Book Library as a way to provide library services for whom conventional print is a barrier due to visual, physical or learning disabilities whether permanent or temporary. The Pinellas Talking Book Library staff provides recorded, Braille and large-print books and magazines as well as a collection of descriptive videos.[67] To serve the emerging deaf community, the Deaf Literacy Center was incorporated into the cooperative in 2001.[61]

Economy

Historical economic strengths

Agriculture was the single most important industry in Pinellas until the early 20th century, with much of the best land devoted to citrus production. Cattle ranching was another major industry. In 1885 the American Medical Society declared the Pinellas peninsula the "healthiest spot on earth",[68] which helped spur the growth of the tourist industry.

Economy today

Anchored by the urban markets of Clearwater and St. Petersburg, Pinellas has the second largest base of manufacturing employment in Florida.

Pinellas has diverse, yet symbiotic, industry clusters, including aviation/aerospace, defense/national security, medical technologies, business and financial services, and information technology.

Fortune 500 technology manufacturers Jabil Circuit and Tech Data and a Fortune 500 financial company Raymond James Financial are headquartered in the Gateway area in and adjacent to Pinellas. Other large companies include HSN, Nielsen, and Valpak.

Service industries such as healthcare, business services and education account for more than 200,000 jobs in the county, generating almost $19 billion in revenue. Other major sectors include retail, with close to 100,000 employees in jobs such as food service, bars, and retail sales generating $12 billion for the local economy in 2010, and industries related to finance, insurance and real estate with approximately 44,000 workers generating $8.5 billion in sales.

Culture

Museums

- Museum of Fine Arts near the Pier in downtown St. Petersburg

- Salvador Dalí Museum in downtown St. Petersburg

- The James Museum of Western & Wildlife Art in downtown St. Petersburg

- Florida Holocaust Museum in downtown St. Petersburg

- Morean Arts Center in downtown St. Petersburg

- Dr. Carter G. Woodson African American Museum in downtown St. Petersburg

- Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art on the Tarpon Springs Campus of St. Petersburg College

- Great Explorations Children's Museum in St. Petersburg

Performing arts venues

- Ruth Eckerd Hall in Clearwater

- Mahaffey Theater in St. Petersburg

- Palladium Theater in St. Petersburg

- Jannus Landing in St. Petersburg

- Palladium at St. Petersburg College in St. Petersburg

- freeFall Theatre in St. Petersburg

- American Stage in St. Petersburg

- Studio@620 in St. Petersburg

The Florida Orchestra splits its performances between Ruth Eckerd Hall, the Mahaffey Theater, and the Straz Center for the Performing Arts in Tampa. Clearwater Jazz Holiday held every October in Coachman Park in downtown Clearwater; in its 32nd year.

Other points of interest

Long established communities, particularly Old Northeast in St. Petersburg, Pass-a-Grille in St. Pete Beach, Harbor Oaks in Clearwater, and old Tarpon Springs contain notable historic architecture.

The area has embraced farmer's markets, with St. Petersburg's Saturday Morning Market drawing large crowds, and other markets located weekly in several other parts of the county also seeing a growth in popularity.

Downtowns in St. Petersburg and Dunedin, and many of the beaches, especially Clearwater Beach, all attract a vibrant nightlife.

In addition to the above-mentioned Heritage Village in Largo, a number of small local history museums operate within the county: the St. Petersburg Museum of History on the downtown St. Petersburg waterfront, the Gulf Beaches Historical Museum in Pass-a-Grille, the Dunedin History Museum in Dunedin, the Palm Harbor Museum in Palm Harbor, and the Historic Depot Museum in Tarpon Springs all provide visitors a glimpse of the area's history.

Two botanical gardens are located within the county: The Florida Botanical Gardens, a part of the Pinewood Cultural Park in Largo, and Sunken Gardens, a former tourist attraction located in and now run by the City of St. Petersburg.

Indian Shores is home to the Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary, currently the largest non-profit wild bird hospital in the United States and considered one of the top avian rehabilitation centers in the world. A variety of species can be found at the sanctuary, which is open 365 days a year and is free to the public.

On Clearwater Beach is the Clearwater Marine Aquarium, a non-profit dedicated to the rescue, rehabilitation and release of injured marine animals and public education. CMA's best-known permanent resident, is Winter, a bottlenose dolphin who was rescued in December 2005 after having her tail caught in a crab trap. Her injuries sadly caused the loss of her tail; CMA successfully fitted Winter with a prosthetic tail which brought worldwide attention to the facility. Winter was the subject of the 2011 film Dolphin Tale, shot partially on location at CMA.

On the south end of Anclote Key, off of Tarpon Springs, is the Anclote Key Light, a lighthouse built in 1887. The light is Pinellas County's only functioning lighthouse, and one of only two in the Tampa Bay Area. The light was deactivated in 1984, but by 2003 had been restored and as of 2013 continues to be in use. The island forms Anclote Key Preserve State Park and is accessible only by private boat.

Dunedin is home to the Dunedin Brewery, Florida's oldest microbrewery.

Sports and recreation

Sports teams

The Tampa Bay Area is home to three major professional sports teams and a number of minor-league and college teams. Regardless of the specific city where they play their games, all of the professional teams claim "Tampa Bay" in their name to signify that they represent the entire area.

Professionally, baseball's Tampa Bay Rays play at Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg, while football's Tampa Bay Buccaneers and hockey's Tampa Bay Lightning both play in nearby Tampa.

Two MLB teams come to Pinellas for spring training: the Philadelphia Phillies play at Spectrum Field in Clearwater while the Toronto Blue Jays play at Florida auto exchange stadium in Dunedin.

Minor League teams in the area include the Clearwater Threshers (formerly the Clearwater Phillies) who play at Spectrum Field and the Dunedin Blue Jays who play Dunedin Stadium.

The North American Soccer League's Tampa Bay Rowdies play at Progress Energy Park in St. Petersburg

The Honda Grand Prix of St. Petersburg is held every spring on the downtown St. Petersburg waterfront.

The PGA Tour plays its Valspar Championship annually in March on the Copperhead Course at the Innisbrook Golf Resort in Palm Harbor.

Recreational areas

- Skyway Fishing Pier State Park - Remnants of the approaches to the original Sunshine Skyway Bridge and the longest fishing pier in the world.

- Fred Marquis Pinellas Trail - 37-mile running and cycling trail over a former railroad bed connecting Tarpon Springs to St. Petersburg.

Other popular fishing locations include Pier 60 on Clearwater Beach and the Gulf and Bay Piers at Fort De Soto Park, as well as countless spots along the bridges and passes of the area, among many others.

Pinellas County's coastal geography, with a long system of barrier islands on the Gulf and small-to-large mangrove islands dotting the waters on all sides, provides for an extensive series of blueways that are enjoyed by kayakers of all ability levels.[69] The county also maintains a series of artificial reefs in the Gulf which are popular spots for fishing and scuba diving[70]

The county's two largest freshwater lakes, Lake Tarpon (accessible through Chestnut and Anderson parks) and Lake Seminole (accessible through Lake Seminole Park), are popular for water skiing, jet-skiing, and sailing, as well as for fishing and kayaking.

Both the North Beach of Fort De Soto Park (2005) and Caladesi Island (2008) have been named by Dr. Beach as America's Top Beach.[71]

Media

Pinellas County, as a part of the Tampa Bay Area (the nation's 14th largest television market[72]), is served by fourteen local broadcast television stations, as well as a variety of cable-only local stations. More than 70 FM and AM stations compete for listenership in what is the nation's 19th largest radio market.[73]

Major daily newspapers serving Pinellas are the Tampa Bay Times, known as the St. Petersburg Times from 1884–2011 and first in circulation and readership, and The Tampa Tribune. The Times also distributes a free daily (Monday-Friday) tabloid called tbt* in the most heavily populated areas of the county. Creative Loafing Tampa is the main alternative weekly.

Transportation

Major highways

Airports

- St. Petersburg–Clearwater International Airport

- Albert Whitted Airport

- Clearwater Executive Airpark

- Tampa International Airport is located across the bay in nearby Tampa.

Railroads

The CSX railroad company operates the Clearwater Subdivision in Pinellas County, made up of segments of branch lines of the former Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and the Seaboard Air Line Railroad. Beginning in Tampa, the line has daily freight rail traffic through Oldsmar, Safety Harbor, Clearwater, Largo, Pinellas Park, and into St. Petersburg. Regularly-scheduled passenger rail services in Pinellas County ended on February 1, 1984 when Amtrak discontinued its rail operations in the county, and the last passenger rail service in the county of any kind, a series of special excursion runs between Tarpon Springs and Dunedin, occurred on March 8, 1987.[74] CSX owned the last remaining trackage in downtown St. Petersburg until March 2008 when it, along with the remaining trackage south of Central Avenue and east of 34th Street South, began to be dismantled.[75] That right-of-way, as well as the right-of-way of several other former CSX railroad lines in the county beginning in the 1990s, was converted into a section of the Pinellas Trail.

As of 2012, proposals are currently being developed[76] by community leaders for a light rail system which would connect the regional core cities of Clearwater, St. Petersburg, and Tampa. The proposal, which has won the backing of the Clearwater and St. Petersburg City Councils[77] would rely on a 1% sales tax and would have to go before voters for approval.

Mass transit

The Pinellas Suncoast Transit Authority (PSTA) operates 205 buses and trolleys servicing 37 routes across the county, with major stops at all commercial centers. Along the Gulf Beaches, PTSA operates the Suncoast Beach Trolley. PTSA also offers two express routes to downtown Tampa via the Howard Frankland and Gandy Bridges, connecting with Tampa's HartLine, and connects with Pasco's PCPT in Tarpon Springs to continue service in that county. The system's two main bus terminals are located in downtown Clearwater and downtown St. Petersburg. During fiscal year 2005-06, PSTA transported 11,400,484 passengers.[78]

Emergency management

Fire departments

- Clearwater Fire Rescue

- Dunedin Fire Rescue

- East Lake Fire Rescue

- Gulfport Fire Rescue

- Largo Fire Rescue

- Lealman Fire District

- Maderia Beach Fire Rescue

- Oldsmar Fire Rescue

- Palm Harbor Fire Rescue

- Pinellas Park Fire Rescue

- Pinellas Suncoast Fire District

- Safety Harbor Fire Rescue

- Seminole Fire Rescue

- St. Pete Beach Fire Rescue

- St. Petersburg Fire Rescue

- South Pasadena Fire Rescue

- Tarpon Springs Fire Rescue

- Treasure Island Fire Rescue

Law enforcement agencies

- Belleair Police Department

- Clearwater Police Department

- Gulfport Police Department

- Indian Shores Police Department

- Kenneth City Police Department

- Largo Police Department

- Pinellas County Sheriff's Office

- Pinellas Park Police Department

- St. Petersburg Police Department

- Tarpon Springs Police Department

- Treasure Island Police Department

Hospitals

- All Children's Hospital- St. Petersburg

- Bay Pines VA Medical Center- Located between St. Petersburg and Seminole in Bay Pines

- Bayfront Medical Center- St. Petersburg. Pinellas County's trauma center which operates Bayflite

- Edward White Hospital- St. Petersburg (closed November 24, 2014)

- HealthSouth Rehabilitation Hospital- Largo

- Florida Hospital North Pinellas - Tarpon Springs

- Largo Medical Center- Largo

- Mease Countryside Hospital- Safety Harbor

- Mease Dunedin Hospital- Dunedin

- Morton Plant Hospital- Clearwater

- Northside Hospital and Tampa Bay Heart Institute- St. Petersburg

- Palms of Pasadena Hospital- South Pasadena

- St. Anthonys Hospital- St. Petersburg

- St. Petersburg General Hospital- St. Petersburg[82]

Communities

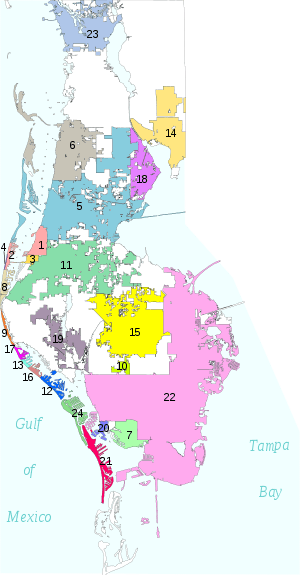

Cities

- Belleair Beach (2)

- Belleair Bluffs (3)

- Clearwater (5)

- Dunedin (6)

- Gulfport (7)

- Indian Rocks Beach (8)

- Largo (11)

- Madeira Beach (12)

- Oldsmar (14)

- Pinellas Park (15)

- Safety Harbor (18)

- Seminole (19)

- South Pasadena (20)

- St. Pete Beach (21)

- St. Petersburg (22)

- Tarpon Springs (23)

- Treasure Island (24)

Towns

- Belleair (1)

- Belleair Shore (4)

- Indian Shores (9)

- Kenneth City (10)

- North Redington Beach (13)

- Redington Beach (16)

- Redington Shores (17)

Census-designated places

Other unincorporated communities

- Baskin

- Crystal Beach

- Curlew

- Gandy

- Highpoint

- Innisbrook

- Oakhurst

- Ozona

- St. George

- Seminole Park

- Wall Springs

- Walsingham

In popular culture

Movies filmed or set in Pinellas County include:

- Gifted (2017)– set in Pinellas County, with scenes in the Pinellas County Courthouse, but filmed in Chatham County, Georgia

- The Infiltrator (2016)– Some scenes filmed at Derby Lane Greyhound Track and St. Pete Beach[83]

- Sunlight Jr. (2013)

- Spring Breakers (2013)

- Magic Mike (2012)–

- Dolphin Tale (2011)– Filmed and set at the Clearwater Marine Aquarium

- Immortal Island (2011)

- A Fonder Heart (2011)– Scenes filmed in Clearwater

- Misconceptions (2008)– scenes filmed at Eckerd College

- Grace is Gone (2007)– scenes filmed at Fort De Soto

- Love Comes Lately (2007)– scenes filmed at Pass A Grille and St. Pete Beach

- Loren Cass (2006)– scenes filmed throughout St. Petersburg

- The Punisher (2004)– Scenes filmed at Honeymoon Island State Park, Fort De Soto and the Sunshine Skyway Bridge

- American Outlaws (2001)– scenes filmed at Fort De Soto

- Ocean's Eleven (2001)– single scene filmed at the Derby Lane Greyhound Track in St. Petersburg

- Great Expectations (1998)– Scenes filmed at Fort DeSoto Park in St. Petersburg

- Lethal Weapon 3 (1992)– scenes filmed at the Soreno Hotel (now gone) in St. Petersburg

- Cocoon (1985)– filmed and set in St. Petersburg

- Summer Rental (1985)– Filmed in St. Pete Beach

- Once Upon a Time in America (1984)– scenes filmed at the historic Don Cesar hotel on St. Pete Beach

- Porky's (1982)– based on actual occurrences at Boca Ciega High School in Gulfport the early 1960s

- HealtH (1980)– filmed entirely at the historic Don Cesar hotel on St. Pete Beach

See also

- Community Service Foundation

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Pinellas County, Florida

- Timeline of Pinellas County, Florida history

- List of tallest buildings in St. Petersburg

References

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "American FactFinder". census.gov. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- "Orlando passes St.Pete: City Beautiful is now Florida's fourth largest city".

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "McMullen-Coachman Log Cabin". Heritage Village. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1995). Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. Gainesville, Florida. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-8130-1636-3.

- "Hillsborough County History". Hillsborough County Official Website.

- "Odet Philippe Marker". hmdb.org. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Pinellas County, Florida, Park and Conservation Resources - Philippe Park". pinellascounty.org. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "ODET PHILIPPE - FLORIDA PIONEE - Genealogy.com". genealogy.com. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "7Brothers". fl-genweb.org. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Twelve-inch mortars". fortdesoto.com. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Pinellas County turns 100 years old". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- http://www.pinellascounty.org/PDF/HEObook.pdf

- "Southpinellas: For Coquina Key, cycle of rum, boom and bust". sptimes.com. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "During World War II, St. Pete had its Bomb-a-Dears". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Andrew Meacham, "Mayor packed ideas, pipe tobacco in rich public life," September 15, 2010". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- "Sunshine Skyway Disaster". sptimes.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2007. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Tampabay: Horrific accident created an unforgettable scene". sptimes.com. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "World's Top 10 Bridges". Travel Channel. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Fact About Pinellas". Pinellas County government. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

Pinellas County is 38 miles long, and 15 miles at it's [sic] broadest point, for a total of 280 square miles. 587 miles of coastline.

- "Pinellas County, Florida - About Pinellas - Facts". pinellascounty.org. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- http://www.pinellascounty.org/Plan/comp_plan/04natural/ch-1.pdf

- http://www.pinellascounty.org/Plan/comp_plan/05coastal/ch-2.pdf

- "Pinellas County Florida - Parks & Preserves". pinellascounty.org. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Boyd Hill Nature Preserve - St. Petersburg, Florida". Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 1, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Mystery Monkey of Tampa Bay finds a home, family in the woods". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "NCDC: U.S. Climate Normals" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- http://www.weather.com/outlook/homeandgarden/home/wxclimatology/monthly/graph/USFL0119

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- "Pinellas County: SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- "Pinellas County Demographic Characteristics". ocala.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- "Miami-Dade County, Florida FIRST ANCESTRY REPORTED Universe: Total population - 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- "Hispanic or Latino by Type: 2010 -- 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- "Pinellas County: Age Groups and Sex: 2010 - 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- "Pinellas County, Florida: SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS - 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- "Demographics Pinellas County, FL". MuniNetGuide.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Modern Language Association Data Center Results of Orange County, Florida". Modern Language Association. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- "Pinellas County, Florida, Board of County Commissioners". pinellascounty.org. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Pinellas County, Florida, Administration". pinellascounty.org. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Tampa Bay Newspapers, County receives A+ for Web site, June 22, 2010".

- https://www.tampabay.com/news/politics/national/five-counties-key-to-floridas-presidential-primary-results/1213103/

- David Leip. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- David Leip. "2010 Senatorial General Election Results - Florida". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Charlie Crist signs papers to become a Democrat". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on February 11, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Month End Voter Statistics". www.votepinellas.com. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- "The Daily Beast".

- "Home." Schiller International University. Retrieved on August 28, 2011 "Main Campus 8560 Ulmerton Road Largo, Florida 33771 "

- Helfand, Lorri. "Largo makes Schiller a priority." Clearwater Times (Edition of St. Petersburg Times). Thursday February 23, 2006. Page 1. Retrieved from Google News (83 of 108) on August 28, 2011.

- "PPLC: About". Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- "Pinellas Public Library Cooperative - Missions and Goals". www.pplc.us. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- "31 Dec 1969, 37 - The Tampa Tribune at Newspapers.com". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- "2 Oct 1990, 51 - Tampa Bay Times at Newspapers.com". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- "PPLC Member Libraries". Archived from the original on February 13, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- "Program Guide". Pinellas Public Library Cooperative. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- "Museum Partnership". Pinellas Public Library Cooperative. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- "Pinellas Talking Book Library". Pinellas Public Library Cooperative. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- webcoast.com

- "Pinellas County Blueways Paddling Guide". pinellascounty.org. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- http://www.pinellascounty.org/utilities/reef/default.htm

- "Dr. Beach: America's Foremost Beach Expert". drbeach.org. Archived from the original on March 5, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 17, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Audio". arbitron.com. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- Luisi 2010, p. 116.

- "Trail enters downtown – A Pinellas Trail extension will reach the waterfront". St. Petersburg Times. March 9, 2008. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- "Transit Leaders Talk Rail in Pinellas". Clearwater, FL Patch. January 20, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "PSTA". Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

- "Pinellas County, Florida - Safety & Emergency Services - Fire Administration". pinellascounty.org. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "History". sunstarems.com. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.siliconbay.org/download/document/20080514_153534_19517.pdf%5B%5D

- https://www.tampabay.com/news/business/tourism/going-to-see-the-infiltrator-here-are-the-spots-around-tampa-bay-that-show/2284934

Bibliography

- Luisi, Vincent (2010), Railroading in Pinellas County (1st ed.), Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7385-8550-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pinellas County, Florida. |

- Official web site with info for businesses, residents, and visitors

- Southwest Florida Water Management District

- USF Map Database Maps of early Pinellas County

- University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Extension in Pinellas County

- Pinellas Watershed Excursion educational interactive guide