Moscow Metro

The Moscow Metro (Russian: Моско́вский метрополите́н, IPA: [mɐˈskofskʲɪj mʲɪtrəpəlʲɪˈtɛn]) is a rapid transit system serving Moscow, Russia, and the neighbouring Moscow Oblast cities of Krasnogorsk, Reutov, Lyubertsy and Kotelniki. Opened in 1935 with one 11-kilometre (6.8 mi) line and 13 stations, it was the first underground railway system in the Soviet Union. As of 2019, the Moscow Metro, excluding the Moscow Central Circle, Moscow Centreal Diameters and Moscow Monorail, has 232 stations (263 with Moscow Central Circle) and its route length is 408.1 km (253.6 mi),[1] making it the fourth longest in the world and longest outside China. The system is mostly underground, with the deepest section 74 metres (243 ft) underground at the Park Pobedy station, one of the world's deepest underground stations. It is the busiest metro system in Europe, and is considered a tourist attraction in itself.[2]

| |||

| |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Native name | Московский метрополитен | ||

| Owner | Government of Moscow | ||

| Locale | Federal city of Moscow and cities of Kotelniki, Krasnogorsk, Lyubertsy, Reutov in the Moscow Oblast Russia | ||

| Transit type | Rapid transit | ||

| Number of lines | 17 (including the Moscow Monorail and the Moscow Central Circle)[1] | ||

| Number of stations | 236[1] 275 (including 6 stations of the Moscow Monorail and 31 stations of the Moscow Central Circle) | ||

| Daily ridership | (average) 6.992 million (highest, Dec. 26, 2014) 9.715 million [1] | ||

| Annual ridership | 2.5 billion (2018)[1] | ||

| Chief executive | Viktor Kozlovsky | ||

| Website | http://mosmetro.ru/ | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | 15 May 1935 | ||

| Operator(s) | Moskovsky Metropoliten | ||

| Headway | Peak hours: 1-2 minutes Off-peak: 4-7 minutes | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 408.1 km (253.6 mi)[1] 466.8 km (290.1 mi) including Moscow Monorail and Moscow Central Circle | ||

| Track gauge | 1,520 mm (4 ft 11 27⁄32 in) | ||

| Electrification | 825 V DC third rail, 3 kV DC overhead line | ||

| Average speed | 39.54 km/h (24.57 mph)[1] | ||

| |||

Operations

The Moscow Metro, a state-owned enterprise,[3] is 381 km (237 mi) long and consists of twelve lines and 223 stations[4] organized in a spoke-hub distribution paradigm, with the majority of rail lines running radially from the centre of Moscow to the outlying areas. The Koltsevaya Line (line 5) forms a 20-kilometre (12 mi) long circle which enables passenger travel between these diameters, and the new Moscow Central Circle (line 14) forms a 54-kilometre (34 mi) longer circle that serves a similar purpose on middle periphery.[5] Most stations and lines are underground, but some lines have at-grade and elevated sections; the Filyovskaya Line, Butovskaya Line and the Central Circle Line are the three lines that are at grade or mostly at grade.

The Moscow Metro uses the Russian gauge of 1,520 millimetres (60 in), like other Russian railways, and an underrunning third rail with a supply of 825 V DC, except line 13 and 14. The average distance between stations is 1.7 kilometres (1.1 mi); the shortest (502 metres (1,647 ft) long) section is between Vystavochnaya and Mezhdunarodnaya and the longest (6.62 kilometres (4.11 mi) long) is between Krylatskoye and Strogino. Long distances between stations have the positive effect of a high cruising speed of 41.7 kilometres per hour (25.9 mph).

The Moscow Metro opens at 05:25 and closes at 01:00.[6] The exact opening time varies at different stations according to the arrival of the first train, but all stations simultaneously close their entrances at 01:00 for maintenance, and so do transfer corridors. The minimum interval between trains is 90 seconds during the morning and evening rush hours.[1]

As of 2017 the system had an average daily ridership of 6.99 million passengers. Peak daily ridership of 9.71 million was recorded on 26 December 2014.[1]

Free wi-fi has been available on all lines of the Moscow Metro since 1 December 2014. The network was launched by MaximaTelecom.

Stations

Of the metro's 232 stations, 88 are deep underground, 123 are shallow, 12 are surface-level and 5 are elevated.

The deep stations comprise 55 triple-vaulted pylon stations, 19 triple-vaulted column stations, and one single-vault station. The shallow stations comprise 79 spanned column stations (a large portion of them following the "centipede" design), 33 single-vaulted stations (Kharkov technology), and three single-spanned stations. In addition, there are 12 ground-level stations, four elevated stations, and one station (Vorobyovy Gory) on a bridge. Two stations have three tracks, and one has double halls. Seven of the stations have side platforms (only one of which is subterranean). In addition, there were two temporary stations within rail yards. One station is reserved for future service (Delovoy Tsentr for the Kalininsko-Solntsevskaya line).

The stations being constructed under Stalin's regime, in the style of socialist classicism, were meant as underground "palaces of the people". Stations such as Komsomolskaya, Kiyevskaya or Mayakovskaya and others built after 1935 in the second phase of the evolution of the network are tourist landmarks, their photogenic architecture, large chandeliers and detailed decoration unusual for an urban transport system.

.jpg) Arbatskaya

Arbatskaya Kiyevskaya

Kiyevskaya Komsomolskaya

Komsomolskaya

Lines

Each line is identified by a name, an alphanumeric index (usually consisting of just a number) and a colour.[7] The colour assigned to each line for display on maps and signs is its colloquial identifier, except for the nondescript greens and blues assigned to the Kakhovskaya, the Zamoskvoretskaya, the Lyublinsko-Dmitrovskaya, and Butovskaya lines (route 11, 2, 10, and 12). The upcoming station is announced by a male voice on inbound trains to the city center (on the Circle line, the clockwise trains) and by a female voice on outbound trains (counter-clockwise trains on the Circle line).[7]

The metro has a connection to the Moscow Monorail, a 4.7-kilometre (2.9 mi), six-station monorail line between Timiryazevskaya and VDNKh which opened in January 2008. Prior to the official opening, the monorail had operated in "excursion mode" since 2004.

| Index & colour |

Transcribed name | Original name | First opened | Latest extension |

Length (km) |

Stations | Avg. dist. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sokolnicheskaya | Сокольническая | 1935 | 2019 | 44.5 | 26 | 1.71 | |

| Zamoskvoretskaya | Замоскворецкая | 1938 | 2018 | 42.8 | 24 | 1.86 | |

| Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya | Арбатско-Покровская | 1938 | 2012 | 45.1 | 22 | 2.15 | |

| Filyovskaya | Филёвская | 1958 (1935)[Note 1] | 2006 | 14.9 | 13 | 1.24 | |

| Koltsevaya (Circle) | Кольцевая | 1950 | 1954 | 19.3 | 12 | 1.61 | |

| Kaluzhsko-Rizhskaya | Калужско-Рижская | 1958 | 1990 | 37.8 | 24 | 1.63 | |

| Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya | Таганско-Краснопресненская | 1966 | 2015 | 42.2 | 23 | 1.92 | |

| Kalininskaya[Note 2] | Калининская | 1979 | 2012 | 16.3 | 8 | 2.36 | |

| Solntsevskaya[Note 2] | Солнцевская | 2014 | 2018 | 24.8 | 12 | 2.26 | |

| Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya | Серпуховско-Тимирязевская | 1983 | 2002 | 41.5 | 25 | 1.72 | |

| Lyublinsko-Dmitrovskaya | Люблинско-Дмитровская | 1995 | 2018 | 38.3 | 23 | 1.74 | |

| Bolshaya Koltsevaya (Big Circle) | Большая кольцевая | 2018 | 2018 | 12.6 | 6 | 2.1 | |

| Butovskaya | Бутовская | 2003 | 2014 | 10.0 | 7 | 1.67 | |

| Nekrasovskaya | Некрасовская | 2019 | 2020 | 22.3 | 10 | 2.3 | |

| Total: | 408.1 | 233 | 1.75 | ||||

| Other urban railway lines: | |||||||

| Moscow Central Circle[Note 3] | Московское центральное кольцо | 2016 | 2016 | 54.0 | 31 | 1.74 | |

| Monorail[Note 4] | Монорельс | 2004 | 2004 | 4.7 | 6 | 0.94 | |

| Belorussko-Savyolovsky diameter | Белорусско-Савёловский диаметр | 2019 | 2020 | 52 | 24 | 2.26 | |

| Kursko-Rizhsky diameter | Курско-Рижский диаметр | 2019 | 2020 | 80 | 34 | 2.42 | |

| Total: | 1935 | 2020 | 598.8 | 328 | 1.83 | ||

| |||||||

Also, from August 11, 1969 to October 26, 2019, the Moscow Metro included ![]()

Renamed lines

Rolling stock

Since the beginning, platforms have been at least 155 metres (509 ft) long to accommodate eight-car trains. The only exceptions are on the Filyovskaya Line: Vystavochnaya, Mezhdunarodnaya, Studencheskaya, Kutuzovskaya, Fili, Bagrationovskaya, Filyovsky Park and Pionerskaya, which only allows six-car trains (note that this list includes all ground-level stations on the line, except Kuntsevskaya, which allows normal length trains).

Trains on the Zamoskvoretskaya, Kaluzhsko-Rizhskaya, Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya, Kalininskaya, Solntsevskaya, Bolshaya Koltsevaya, Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya, Lyublinsko-Dmitrovskaya and Nekrasovskaya lines have eight cars, on the Sokolnicheskaya line seven or eight cars and on the Filyovskaya line six cars. The Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya and Koltsevaya lines had six- and seven-car trains as well, but now use five-car trains of another type. Butovskaya line uses three-car trains of another type.

| Rolling Stock for Moscow Metro | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car | Delivered | In service | ||

| А/Б ("A/B") | 1934–39 | 1935–75 | ||

| B ("V", earlier C) | 1927–30 | 1946–68 | ||

| Г ("G") | 1939–40, 1946–56 | 1940–83 | ||

| Д ("D") | 1955–63 | 1955–95 | ||

| E/Ем/Еж ("E/Em/Ezh") | 1959–79 | 1962 ff. | ||

| 81-717/714 | 1976–2011 | 1977 ff. | ||

| И ("I", 81-715/716) | 1974, 80–81, 85 | — | ||

| 81-720/721 "Yauza" | 1991–2004 | 1998–2019 | ||

| 81-740/741 "Rusich" | 2002–2013 | 2003 ff. | ||

| 81-760/761 "Oka" | 2010–2016 | 2012 ff. | ||

| 81-765/766/767 "Moskva" | 2016–2020 | 2017 ff. | ||

| 81-775/776/777 "Moskva 2020" | 2020 ff. | 2020 ff. | ||

World War II

The V-type trains were formerly from Berlin U-Bahn C-class trains from 1945 to 1969, until its complete demise in 1970. They were transported from the Berlin U-Bahn during the Soviet occupation. A-type and B-type trains were custom-made since the opening.

.jpg) A-type

A-type B-type

B-type V-4-type (former Berlin Class C-1)

V-4-type (former Berlin Class C-1).jpg) V2-type (former Berlin Class C-2)

V2-type (former Berlin Class C-2)

Modern Era

Currently, the Metro only operates 81-style trains.

Rolling stock on the Koltsevaya line is being replaced with articulated 81-740/741 Rusich four-car trains. The Butovskaya Line was designed by different standards, and has shorter (96-metre (315 ft) long) platforms. It employs articulated 81-740/741 trains, which consist of three cars (although the line can also use traditional four-car trains). On the Moscow Central Circle, Lastochka trains are used, consisting of five cars.

G-type

G-type D-type

D-type E-type

E-type I-2-type (81-715.2/716.2)

I-2-type (81-715.2/716.2)

81-717.5A/81-714.5A-type

81-717.5A/81-714.5A-type.jpg) 81-717.6-714.6-type

81-717.6-714.6-type

81-765/766/767-type ("Moscow")

81-765/766/767-type ("Moscow") Intamin P30 train (operates on the Monorail line)

Intamin P30 train (operates on the Monorail line) ES2G Lastochka train (operates on the Moscow Central Circle line)

ES2G Lastochka train (operates on the Moscow Central Circle line)

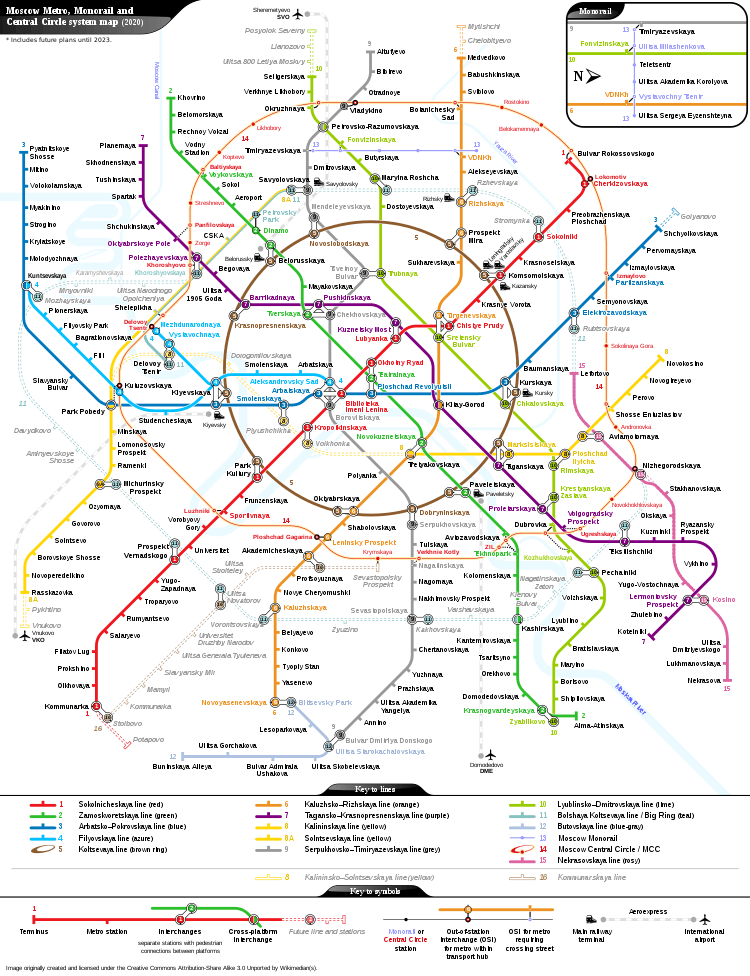

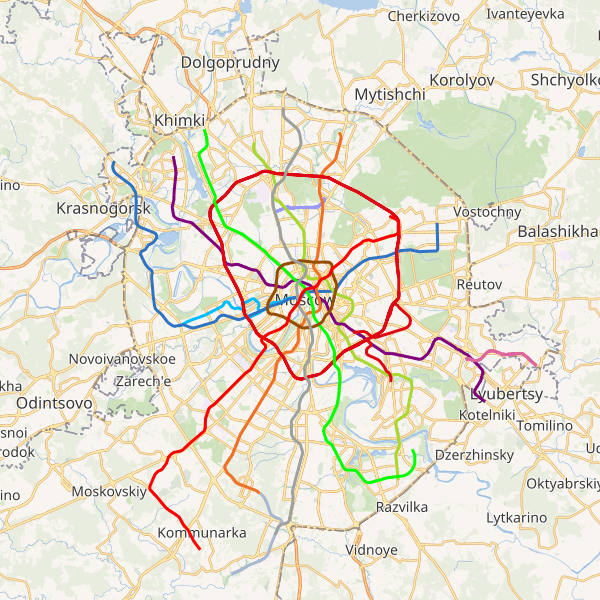

Network map

History

The first plans for a metro system in Moscow date back to the Russian Empire but were postponed by World War I, the October Revolution and the Russian Civil War. In 1923, the Moscow City Council formed the Underground Railway Design Office at the Moscow Board of Urban Railways. It carried out preliminary studies, and by 1928 had developed a project for the first route from Sokolniki to the city centre. At the same time, an offer was made to the German company Siemens Bauunion to submit its own project for the same route. In June 1931, the decision to begin construction of the Moscow Metro was made by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In January 1932 the plan for the first lines was approved, and on 21 March 1933 the Soviet government approved a plan for 10 lines with a total route length of 80 km (50 mi).

The first lines were built using the Moscow general plan designed by Lazar Kaganovich, along with his project managers (notably Ivan M. Kuznetsov and, later, Isaac Y. Segal) in the 1930s-1950s, and the Metro was named after him until 1955 (Metropoliten im. L.M. Kaganovicha).[8] The Moscow Metro construction engineers consulted with their counterparts from the London Underground, the world's oldest metro system. Partly because of this connection, the design of the Gants Hill tube station in London, which was completed much later, is reminiscent of a Moscow Metro station.[9][10]

Soviet workers did the labor and the art work, but the main engineering designs, routes, and construction plans were handled by specialists recruited from the London Underground. The Britons called for tunneling instead of the "cut-and-cover" technique, the use of escalators instead of lifts, the routes and the design of the rolling stock.[11] The paranoia of the NKVD was evident when the secret police arrested numerous British engineers for espionage because they gained an in-depth knowledge of the city's physical layout. Engineers for the Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Company (Metrovick) were given a show trial and deported in 1933, ending the role of British business in the USSR.[12]

First four stages of construction

The first line was opened to the public on 15 May 1935 at 07:00 am.[13] It was 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) long and included 13 stations. The day was celebrated as a technological and ideological victory for socialism (and, by extension, Stalinism). An estimated 285,000 people rode the Metro at its debut, and its design was greeted with pride; street celebrations included parades, plays and concerts. The Bolshoi Theatre presented a choral performance by 2,200 Metro workers; 55,000 colored posters (lauding the Metro as the busiest and fastest in the world) and 25,000 copies of "Songs of the Joyous Metro Conquerors" were distributed.[14] This publicity barrage, produced by the Soviet government, stressed the superiority of the Moscow Metro over all other metros in capitalist societies and the Metro's role as a prototype for the Soviet future. The Moscow Metro averaged 47 km/h (29 mph) and had a top speed of 80 km/h (50 mph).[15] In comparison, New York City Subway trains averaged a slower 25 miles per hour (40 km/h) and had a top speed of 45 miles per hour (72 km/h).[14] While the celebration was an expression of popular joy it was also an effective propaganda display, legitimizing the Metro and declaring it a success.

The initial line connected Sokolniki to Okhotny Ryad then branching to Park Kultury and Smolenskaya.[16] The latter branch was extended westwards to a new station (Kiyevskaya) in March 1937, the first Metro line crossing the Moskva River over the Smolensky Metro Bridge.

The second stage was completed before the war. In March 1938, the Arbatskaya branch was split and extended to the Kurskaya station (now the dark-blue Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Line). In September 1938, the Gorkovskaya Line opened between Sokol and Teatralnaya. Here the architecture was based on that of the most popular stations in existence (Krasniye Vorota, Okhotnyi Ryad and Kropotkinskaya); while following the popular art-deco style, it was merged with socialist themes. The first deep-level column station Mayakovskaya was built at the same time.

Building work on the third stage was delayed (but not interrupted) during World War II, and two Metro sections were put into service; Teatralnaya–Avtozavodskaya (three stations, crossing the Moskva River through a deep tunnel) and Kurskaya–Partizanskaya (four stations) were inaugurated in 1943 and 1944 respectively. War motifs replaced socialist visions in the architectural design of these stations. During the Siege of Moscow in the fall and winter of 1941, Metro stations were used as air-raid shelters; the Council of Ministers moved its offices to the Mayakovskaya platforms, where Stalin made public speeches on several occasions. The Chistiye Prudy station was also walled off, and the headquarters of the Air Defence established there.

After the war ended in 1945, construction began on the fourth stage of the Metro, which included the Koltsevaya Line, a deep part of the Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya line from Ploshchad Revolyutsii to Kievskaya and a surface extension to Pervomaiskaya during the early 1950s. The decoration and design characteristic of the Moscow Metro is considered to have reached its zenith in these stations. The Koltsevaya Line was first planned as a line running under the Garden Ring, a wide avenue encircling the borders of Moscow's city centre. The first part of the line – from Park Kultury to Kurskaya (1950) – follows this avenue. Plans were later changed and the northern part of the ring line runs 1–1.5 kilometres (0.62–0.93 mi) outside the Sadovoye Koltso, thus providing service for seven (out of nine) rail terminals. The next part of the Koltsevaya Line opened in 1952 (Kurskaya–Belorusskaya), and in 1954 the ring line was completed.

Cold War era

The beginning of the Cold War led to the construction of a deep section of the Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Line. The stations on this line were planned as shelters in the event of nuclear war. After finishing the line in 1953 the upper tracks between Ploshchad Revolyutsii and Kiyevskaya were closed, and later reopened in 1958 as a part of the Filyovskaya Line. In the further development of the Metro the term "stages" was not used any more, although sometimes the stations opened in 1957–1959 are referred to as the "fifth stage".

Other stations, too, were supplied with tight gates and life-sustenance systems to function as nuclear shelters.

During the late 1950s the architectural extravagance of new Metro stations was toned down, and decorations at some stations (such as VDNKh and Alexeyevskaya) were simplified by comparison with the original plans. This was done on the orders of Nikita Khrushchev, who favoured more spartan decoration. A typical layout (which quickly became known as Sorokonozhka–"centipede", from early designs with 40 concrete columns in two rows) was developed for all new stations and the stations were built to look almost identical, differing from each other only in colours of the marble and ceramic tiles. Most stations were built with simpler, less-costly technology; this was not always appropriate, and resulted in utilitarian design. For example, walls with cheap ceramic tiles were susceptible to train vibration and some tiles eventually fell off. It was not always possible to replace the missing tiles with the ones of the same color, which eventually led to variegated parts of the walls. Not until the mid-1970s was the architectural extravagance restored and original designs again popular. However, the newer design of "centipede" stations (with 26 columns, more widely spaced) continued to dominate.

Stalinist ideals

Publicizing the metro

The Moscow Metro was one of the USSR's most ambitious architectural projects. The metro's artists and architects worked to design a structure that embodied svet (radiance or brilliance) and svetloe budushchee (a radiant future).[17] With their reflective marble walls, high ceilings and grand chandeliers, many Moscow Metro stations have been likened to an "artificial underground sun".[18] This palatial underground environment[18] reminded riders that their tax rubles had been well spent on svetloe budushchee.

The chief lighting engineer was Abram Damsky, a graduate of the Higher State Art-Technical Institute in Moscow. By 1930 he was a chief designer in Moscow's Elektrosvet Factory, and during World War II was sent to the Metrostroi (Metro Construction) Factory as head of the lighting shop.[19] Damsky recognized the importance of efficiency, as well as the potential for light as an expressive form. His team experimented with different materials (most often cast bronze, aluminum, sheet brass, steel, and milk glass) and methods to optimize the technology.[19] Damsky's discourse on "Lamps and Architecture 1930–1950" describes in detail the epic chandeliers installed in the Kaluzhskaia (now called the Oktiabrskaia) Station and the Taganskaia Station:

The Kaluzhskaya Station was designed by the architect [Leonid] Poliakov. Poliakov's decision to base his design on a reinterpretation of Russian classical architecture clearly influenced the concept of the lamps, some of which I planned in collaboration with the architect himself. The shape of the lamps was a torch – the torch of victory, as Poliakov put it... The artistic quality and stylistic unity of all the lamps throughout the station's interior made them perhaps the most successful element of the architectural composition. All were made of cast aluminum decorated in a black and gold anodized coating, a technique which the Metrostroi factory had only just mastered.

The Taganskaia Metro Station on the Ring Line was designed in...quite another style by the architects K.S. Ryzhkov and A. Medvedev... Their subject matter dealt with images of war and victory...The overall effect was one of ceremony ... In the platform halls the blue ceramic bodies of the chandeliers played a more modest role, but still emphasised the overall expressiveness of the lamp.[19]

— Abram Damsky, Lamps and Architecture 1930–1950

The work of Abram Damsky further publicized these ideas hoping people would associate the party with svetloe budushchee.

Industrialization

Stalin's first five-year plan (1928–1932) facilitated rapid industrialization to build a socialist motherland. The plan was ambitious, seeking to reorient an agrarian society towards industrialism. It was Stalin's fanatical energy, large-scale planning, and smart resource distribution that kept up the incredible pace of industrialization. The first five-year plan was instrumental in the completion of the Moscow Metro; without industrialization, the Soviet Union would not have had the raw materials necessary for the project. For example, steel was a main component of many subway stations. Before industrialization, it would have been impossible for the Soviet Union to produce enough steel to incorporate it into the metro's design; in addition, a steel shortage would have limited the size of the subway system and its technological advancement.

The Moscow Metro furthered the construction of a socialist Soviet Union because the project accorded with Stalin's second five-year plan. The Second Plan focused on urbanization and the development of social services. The Moscow Metro was necessary to cope with the influx of peasants who migrated to the city during the 1930s; Moscow's population had grown from 2.16 million in 1928 to 3.6 million in 1933. The Metro also bolstered Moscow's shaky infrastructure and its communal services, which hitherto were nearly nonexistent.[14]

Mobilization

The Communist Party had the power to mobilize; because the party was a single source of control, it could focus its resources and inspire its people. The most notable example of mobilization in the Soviet Union occurred during World War II. The country also mobilized in order to complete the Moscow Metro with unprecedented speed. One of the main motivation factors of the mobilization was to overtake the West and prove that a socialist metro could surpass capitalist designs. It was especially important to the Soviet Union that socialism succeed industrially, technologically, and artistically in the 1930s, since capitalism was at a low ebb during the Great Depression.

The person in charge of Metro mobilization was Lazar Kaganovich. A prominent Party member, he assumed control of the project as chief overseer. Kaganovich was nicknamed the "Iron Commissar"; he shared Stalin's fanatical energy, dramatic oratory flare, and ability to keep workers building quickly with threats and punishment.[14] He was determined to realise the Moscow Metro, regardless of cost. Without Kaganovich's managerial ability, the Moscow Metro might have met the same fate as the Palace of the Soviets: failure.

This was a comprehensive mobilization; the project drew resources and workers from the entire Soviet Union. In his article, archeologist Mike O'Mahoney describes the scope of the Metro mobilization:

A specialist workforce had been drawn from many different regions, including miners from the Ukrainian and Siberian coalfields and construction workers from the iron and steel mills of Magnitogorsk, the Dniepr hydroelectric power station, and the Turkestan-Siberian railway... materials used in the construction of the metro included iron from Siberian Kuznetsk, timber from northern Russia, cement from the Volga region and the norther Caucasus, bitumen from Baku, and marble and granite from quarries in Karelia, the Crimea, the Caucasus, the Urals, and the Soviet Far East[20]

— Mike O'Mahoney, Archeological Fantasies: Constructing History on the Moscow Metro

Skilled engineers were scarce, and unskilled workers were instrumental to the realization of the metro. The Metrostroi (the organization responsible for the Metro's construction) conducted massive recruitment campaigns. It printed 15,000 copies of Udarnik metrostroia (Metrostroi Shock Worker, its daily newspaper) and 700 other newsletters (some in different languages) to attract unskilled laborers. Kaganovich was closely involved in the recruitment campaign, targeting the Komsomol generation because of its strength and youth.

Patriotic influences

When the Metro opened in 1935 it immediately became the centrepiece of the transportation system. More than that, it was a Stalinist device to awe and control the populace, and give them an appreciation of Soviet realist art. It became the prototype for future Soviet large-scale technologies. Kaganovich was in charge; he designed the subway so that citizens would absorb the values and ethos of Stalinist civilization as they rode. The artwork of the 13 original stations became nationally and internationally famous. For example, the Sverdlov Square subway station featured porcelain bas-reliefs depicting the daily life of the Soviet peoples, and the bas-reliefs at the Dynamo Stadium sports complex glorified sports and physical prowess on the powerful new "Homo Sovieticus" (Soviet man).[21] The metro was touted as the symbol of the new social order—a sort of Communist cathedral of engineering modernity.[22]

The Metro was iconic also because it showcased Socialist Realism in public art. Socialist Realism was in fact a method, not a style.[17] This method was influenced by Nikolay Chernyshevsky, Lenin's favorite 19th-century nihilist, who stated that "art is no use unless it serves politics".[14] This maxim explains why the stations combined aesthetics, technology and ideology. Any plan which did not incorporate all three areas cohesively was rejected. Without this cohesion, the Metro would not reflect Socialist Realism. If the Metro did not utilize Socialist Realism, it would fail to illustrate Stalinist values and transform Soviet citizens into socialists. Anything less than Socialist Realism's grand artistic complexity would fail to inspire a long-lasting, nationalistic attachment to Stalin's new society.[23]

Moscow Central Circle urban railway (Line 14)

A proposal to convert the Little Ring of the Moscow Railway into a metropolitan railway with frequent passenger service was announced in 2012. New track was laid and stations were built between 2014 and 2016. The Moscow Central Circle line (Line 14) opened to passengers in September 2016, relieving congestion on the Koltsevaya line. Line 14 is operated by Russian Railways. Free transfers are permitted between the MCC and the Moscow Metro if the trip before the transfer is less than 90 minutes.[24]

Logo

The first line of the Moscow Metro was launched in 1935, complete with the first logo, the capital M paired with the text "МЕТРО". There is no accurate information about the author of the logo, so it is often attributed to the architects of the first stations – Samuil Kravets, Ivan Taranov and Nadezhda Bykova. It is noteworthy, however, that even at the opening in 1935, the M letter on the logo had no definite shape.[25]

Today, with at least ten different variations of the shape in use, Moscow Metro still does not have clear brand or logo guidelines. An attempt was made in October 2013 to launch a nationwide brand image competition, only to be closed several hours after its announcement. A similar contest, held independently later that year by the design crowdsourcing company DesignContest, yielded better results, though none were officially accepted by the Metro officials.[26][27]

Ticketing

_(7221508840).jpg)

From the 1960s to the 1990s, the cost of a ride was five kopecks (1/20 of a Soviet ruble). The fare has been steadily rising since 1991, hastened by inflation (taking into account the 1998 revaluation of the ruble by a factor of 1,000). Effective February 2017, one ride costs 55 rubles (approx. 1 US dollar). Discounts (up to 33 percent) are available when buying a multiple-trip ticket (starting with twenty-trip cards), and children under age seven can travel free with their parents.

Tickets are available for a fixed number of trips, regardless of distance traveled or number of transfers. Monthly and yearly passes are also available. Fare enforcement takes place at the points of entry. Once a passenger has entered the Metro system, there are no further ticket checks – one can ride to any number of stations and make transfers within the system freely. Transfers to other public-transport systems (such as bus, tram, trolleybus) are not covered by the ticket. Transfer to monorail is free within 90 minutes.

Before 1991, turnstiles accepted coins; however, with the start of hyperinflation plastic tokens of various design were used. Disposable magnetic stripe cards were introduced in 1993 on a trial basis, and used as unlimited monthly tickets between 1996 and 1998. The sale of tokens ended on 1 January 1999, and they stopped being accepted in February 1999; from that time, magnetic cards were used as tickets with a fixed number of trips.

On 1 September 1998, the Moscow Metro became the first metro system in Europe to fully implement contactless smart cards, known as Transport Cards. The card has an unlimited number of trips and may be programmed for 30, 90 or 365 days. The first purchase includes a one-time cost of 50 rubles, and its active lifetime is projected as 3½ years; defective cards are exchanged at no cost. Unlimited cards are also available for students at reduced price (as of 2017, 365 rubles—or about $US6—for a calendar month of unlimited usage) for a one-time cost of 70 rubles. Transport Cards impose a delay for each consecutive use; i.e. the card can not be used for seven minutes after the user has passed through the turnstile.

In January 2007, Moscow Metro began replacing magnetic cards with contactless disposable tickets based on NXP's MIFARE Ultralight technology. Ultralight tickets are available for a fixed number of trips in 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 60-trip denominations (valid for 5 or 90 days from the day of purchase) and as a monthly ticket, only valid for a selected calendar month and limited to 70 trips. The sale of magnetic cards stopped 16 January 2008 and magnetic cards stopped being accepted in late 2008, making the Moscow metro the world's first major public-transport system to run exclusively on a contactless automatic fare-collection system.[28]

In August 2004, the city government launched the Muscovite's Social Card program. Social Cards are free smart cards issued for the elderly and other groups of citizens officially registered as residents of Moscow or the Moscow region; they offer discounts in shops and pharmacies, and double as credit cards issued by the Bank of Moscow. Social Cards can be used for unlimited free access to the city's public-transport system, including the Moscow Metro; while they do not feature the time delay, they include a photograph and are non-transferable.

Since 2006, several banks have issued credit cards which double as Ultralight cards and are accepted at turnstiles. The fare is passed to the bank and the payment is withdrawn from the owner's bank account at the end of the calendar month, using a discount rate based on the number of trips that month (for up to 70 trips, the cost of each trip is prorated from current Ultralight rates; each additional trip costs 24.14 rubles).[29] Partner banks include the Bank of Moscow, CitiBank, Rosbank, Alfa-Bank and Avangard Bank.[30]

On 2 April 2013 Moscow Transport Department introduced a smart card based transport electronic wallet called Troika. There are also three more smart cards has been launched - Ediniy card, a universal card for all city-owned public transport operated by Mosgortrans and Moscow Metro, 90 minutes card, an unlimited "90-minute" card and TAT card for surface public transport operated by Mosgortrans.[31]

In 2013, as a way to promote both the "Olympic Games in Sochi and active lifestyles, Moscow Metro installed a vending machine that gives commuters a free ticket in exchange for doing 30 squats."[32]

From the first quarter of 2015 ticket windows at stations started to accept bank cards for fare payment. Passengers were also able to start using contactless payment systems, such as PayPass technology on MasterCard and Maestro Visa PayWave on Visa cards, at fare gates to enter the system.

Fare gates at stations started in September 2015 to accept payment using mobile ticketing, a system which the Metro calls Mobile Ticket (Мобильный билет). Customers wishing to use this method of payment must exchange their existing SIM card for one that supports Near Field Communication technology. Applicable fares are the same as on the Troika card.

Customers are able to use Mobile Ticket on Moscow's surface transport.[33]

The Moscow Metro originally announced plans to launch the mobile ticketing service with Mobile TeleSystems (MTS) in 2010.[34]

Fares

| Trip limit |

Cost | Cost per trip |

Discount | Valid for |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed-rate Ultralight ticket (for each pass in metro or ground transport in zone "A" and "B"). You can use a multipass ticket for a group in the metro (touch once for each passenger), in ground transport smart cards for only one person. | ||||

| 1 (sold by all ticket machines) | 55 | 55 | 0.0% | 5 days |

| 2 (sold by some ticket machines) | 110 | 55 | 0.0% | 5 days |

| 60 (no paper ticket can be purchased, Troika only) | 1,900 | 31,6 | 42.4% | 45 days |

| 1 (Troika electronic wallet) | 38 | 38 | 30.9% | – |

| 90 minutes Allows passenger to take one journey on Moscow Metro (Moscow Central Circle and Moscow Monorail) included, and unlimited number of journeys on buses, trams, and trolleybuses. All the journeys have to be started within 90 minutes of the first one. | ||||

| 1 (Troika electronic wallet) | 59 | 59 | 46.3% (compared to two singles) | – |

| Transport Card (Metro and bus) | ||||

| unlimited for 1 day, 20 min delay (except MCC and monorail interchanges) | 230 | – | 24 hours from the first pass which should be within 10 days of sale | |

| unlimited for 3 days, 20 min delay (except MCC and monorail interchanges) | 438 | – | 72 hours from the first pass which should be within 10 days of sale | |

| unlimited for 30 days, 7 min delay (no paper ticket, no delay for interchanges) | 2,170 | – | 30 days from the date of sale | |

| unlimited for 90 days, 7 min delay (only in Troika) | 5,430 | – | 90 days from the date of sale | |

| unlimited for 365 days, 7 min delay (only in Troika) | 19,500 | – | 365 days from the date of sale | |

| Preferential transport card (for Moscow pupils and students) | ||||

| unlimited, 7 min delay | 395 | – | --- | calendar month |

Note: The real discount is higher because validity period is doubled (90 days is enough to pass even twice only in the week days).

There is no difference between types of transport for fare collection, the difference apply for carrier.

Note: in main fare zone is the territory: (in some area 2 fare systems have track overlap, these areas are not written above).

- Routes in MKAD borders (include all trolleybusses routes inside MKAD and all trams),

- Butovo

- Solntsevo-Novoperedelkino

- Zelenograd

| Effective date | Price | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1935-05-15 | 50 kopecks | |

| 1935-08-01 | 40 kopecks | with season ticket — 35 kopecks |

| 1935-10-01 | 30 kopecks | with season ticket — 25 kopecks |

| 1942-05-31 | 40 kopecks | |

| 1948-08-16 | 50 kopecks | Not taking into account 10x denomination of 1947. In fact, the fare increased 10 times. |

| 1961-01-01 | 5 kopecks | redenomination |

| 1991-04-02 | 15 kopecks | |

| 1992-03-01 | 50 kopecks | |

| 1992-06-24 | 1 ruble | |

| 1992-12-01 | 3 rubles | |

| 1993-02-16 | 6 rubles | |

| 1993-06-25 | 10 rubles | |

| 1993-10-15 | 30 rubles | |

| 1994-01-01 | 50 rubles | |

| 1994-03-18 | 100 rubles | |

| 1994-06-23 | 150 rubles | |

| 1994-09-21 | 250 rubles | |

| 1994-12-20 | 400 rubles | |

| 1995-03-20 | 600 rubles | |

| 1995-07-21 | 800 rubles | |

| 1995-09-20 | 1,000 rubles | |

| 1995-12-21 | 1,500 rubles | |

| 1997-06-11 | 2,000 rubles | |

| 1998-01-01 | 2 rubles | Redenomination due to post-Soviet period inflation |

| 1998-09-01 | 3 rubles | |

| 1999-01-01 | 4 rubles | |

| 2000-07-15 | 5 rubles | |

| 2002-10-01 | 7 rubles | |

| 2004-04-01 | 10 rubles | |

| 2005-01-01 | 13 rubles | Monorail fare is 50 rubles (25 rubles discount fare), no other tickets are valid on monorail |

| 2006-01-01 | 15 rubles | |

| 2007-01-01 | 17 rubles | |

| 2008-01-01 | 19 rubles | Monorail fare is equal to the metro fare (reduced to 19 rubles), and only special monthly tickets also available and valid on this line |

| 2009-01-01 | 22 rubles | |

| 2010-01-01 | 26 rubles | |

| 2011-01-01 | 28 rubles | Russian Railways fare in Moscow fare principles are separated and the fare did not increased (26 rubles) unlike the earlier years. |

| 2013-01-01 | 28 rubles | minor change: Monorail fare included in all metro fares, first transfer in 90 minutes does not charge |

| 2013-04-02 | 30 rubles | Single journey fare increased. Most other kinds of fares are lowered. New: 90 minute fare. |

| 2014-01-01 | 30-40 rubles | Single and double fare increased. 5-60 pass fare, and all 90 minute fare are stayed. Russian railway fare in Moscow increased to 28 rubles. |

| 2016-01-01 | 32-50 rubles | All ticket fares increased. Single fare increased to 50 rubles or 32 rubles (by Troika e-wallet). All unlimited fare are stayed.[35] |

| 2017-01-01 | 35-55 rubles | All ticket fares increased. Single fare increased to 55 rubles or 35 rubles (by Troika e-wallet). All |-unlimited fare are stayed. |

| 2018-01-02 | 36-55 rubles | Single fare increased by 1 ruble, only while paying by Troika e-wallet. 90 minutes fare increased from 54 to 56 rubles. |

| 2019-01-02 | 38-55 rubles | Single fare increased by 2 rubles, while paying Troika card. 90 minutes tickets increased by 3 rubles. |

Expansions

Since the turn of the 21st century several projects have been completed, and more are underway. The first was the Annino-Butovo extension, which extended the Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya Line from Prazhskaya to Ulitsa Akademika Yangelya in 2000, Annino in 2001 and Bulvar Dmitriya Donskogo in 2002. Its continuation, an elevated Butovskaya Line, was inaugurated in 2003. Vorobyovy Gory station, which initially opened in 1959 and was forced to close in 1983 after the concrete used to build the bridge was found to be defective, was rebuilt and reopened after many years in 2002. Another recent project included building a branch off the Filyovskaya Line to the Moscow International Business Center. This included Vystavochnaya (opened in 2005) and Mezhdunarodnaya (opened in 2006).

The Strogino–Mitino extension began with Park Pobedy in 2003. Its first stations (an expanded Kuntsevskaya and Strogino) opened in January 2008, and Slavyansky Bulvar followed in September. Myakinino, Volokolamskaya and Mitino opened in December 2009. Myakinino station was built by a state-private financial partnership, unique in Moscow Metro history.[36] A new terminus, Pyatnitskoye Shosse, was completed in December 2012.

After many years of construction, the long-awaited Lyublinskaya Line extension was inaugurated with Trubnaya in August 2007 and Sretensky Bulvar in December of that year. In June 2010, it was extended northwards with the Dostoyevskaya and Maryina Roscha stations. In December 2011, the Lyublinskaya Line was expanded southwards by three stations and connected to the Zamoskvoretskaya Line, with the Alma-Atinskaya station opening on the latter in December 2012. The Kalininskaya Line was extended past the Moscow Ring Road in August 2012 with Novokosino station.

In 2011 works began on the Third Interchange Contour that is set to take the pressure off the Koltsevaya Line.[37] Eventually the new line will attain a shape of the second ring with connections to all lines (except Koltsevaya and Butovskaya).[38]

In 2013 the Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya Line was extended after several delays to the south-eastern districts of Moscow outside the Ring Road with the opening of Zhulebino and Lermontovsky Prospekt stations. Originally scheduled for 2013, a new segment of the Kalininskaya Line between Park Pobedy and Delovoy Tsentr (separate from the main part) was opened in January 2014, while the underground extension of Butovskaya Line northwards to offer a transfer to the Kaluzhsko-Rizhskaya Line was completed in February. Spartak, a station on the Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya Line that remained unfinished for forty years, was finally opened in August 2014. The first stage of the southern extension of the Sokolnicheskaya Line, the Troparyovo station, opened in December 2014.

Current plans

The Moscow Metro is undergoing a major expansion; current plans call for almost 150 kilometres (93 mi) of new lines to be opened between 2012–2022. There were 15 tunnel boring machines working in Moscow as of April 2013 with 24 planned by the end of 2013.[39][40]

In addition to major metro expansion the Moscow Government and Russian Railways plans to upgrade more commuter railways to a metro-style service, similar to the MCC. New tracks and stations are planned to be built in order to achieve this.

| Line | Terminals | Length (km) | Stations | Status | Planned opening | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lefortovo | Elektrozavodkaya | 2.9 | 1 | Under construction | 2020 | |

| Khoroshyovskaya | Karamyshevskaya | 5.0 | 2 | Under construction | 2020–2021 | |

| Kakhovskaya | Aminyevskaya | ~11 | 6 | Under construction | 2021 | |

| Aminyevskaya | Karamyshevskaya | ~8 | 3 | Under construction | 2021–2022 | |

| Aprelevka | Zheleznodorozhny | 85 | Under construction | 2021–2022 | ||

| Seligerskaya | Lianozovo | 3.9 | 2 | Under construction | 2022 | |

| Nizhegorodskaya | Kashirskaya | 11.4 | 4 | Under construction | 2022 | |

| Kashirskaya | Kakhovskaya | 3.3 | 2 | Under renovation | 2022 | |

| Elektrozavodkaya | Savyolovskaya | 7.2 | 3 | Under construction | 2022 | |

| Rasskazovka | Vnukovo | 5.5 | 2 | Under construction | 2022–2023 | |

| Ulitsa Novatorov | Stolbovo | 16.3 | 7 | Under construction | 2023 | |

| Lianozovo | Fiztekh | 3.0 | 1 | Planned | ||

| Kommunarka | Novomoskovskaya | 2.4 | 1 | Planned | ||

| Ulitsa Novatorov | Krymskaya | 7.3 | 3 | Planned | ||

| Shchyolkovskaya | Golianovo | 1 | Planned | |||

| Tretyakovskaya | Delovoy Tsentr | 5.1 | 3 | Planned | ||

| Stolbovo | Troitsk | 6 | Planned | |||

| Alabushevo | Ippodrom | 82 | Planned | 2023–2024 | ||

| Total under construction (underground lines): | ~75 km | 32 | ||||

| Total under construction (onground lines): | 217 km | |||||

Metro 2

It has been alleged that a second and deeper metro system code-named "D-6",[41] designed for emergency evacuation of key city personnel in case of nuclear attack during the Cold War, exists under military jurisdiction. It is believed that it consists of a single track connecting the Kremlin, chief HQ (General Staff–Genshtab), Lubyanka (FSB Headquarters), the Ministry of Defence and several other secret installations. There are alleged to be entrances to the system from several civilian buildings, such as the Russian State Library, Moscow State University (MSU) and at least two stations of the regular Metro. It is speculated that these would allow for the evacuation of a small number of randomly chosen civilians, in addition to most of the elite military personnel. A suspected junction between the secret system and the regular Metro is supposedly behind the Sportivnaya station on the Sokolnicheskaya Line. The final section of this system was supposedly completed in 1997.[42]

Statistics

.jpg)

| Ridership statistics | |

|---|---|

| Passengers (2018) | 2,500,400,000 passengers[1] |

| —— full-fare | 1,812,900,000 passengers |

| —— privileged category | 473,500,000 passengers |

| —— pupils and students | 214,000,000 passengers |

| Maximum daily ridership | 9,715,635 passengers |

| Revenue from fares (2005) | 15.9974 billion rubles |

| Average passenger trip | 14.93 kilometres (9.28 mi) |

| Line statistics | |

| Total lines length | 333.3 kilometres (207.1 mi) |

| Number of lines | 15 |

| Longest line | Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Line (43.5 kilometres (27.0 mi)) |

| Shortest line | Kakhovskaya Line (3.3 kilometres (2.1 mi)) |

| Longest section | Strogino–Krylatskoye (6.7 kilometres (4.2 mi)) |

| Shortest section | Vystavochnaya–Mezhdunarodnaya (502 metres (1,647 ft)) |

| Station statistics | |

| Number of stations | 228 |

| — transfer stations | 68 |

| — transfer points | 29 |

| — surface/elevated | 16 |

| Deepest station | Park Pobedy (84 metres (276 ft)) |

| Shallowest underground station | Pechatniki |

| Station with the longest platform | Vorobyovy Gory (Metro) (282 metres (925 ft)) |

| Number of stations with a single entrance | 73 |

| Infrastructure statistics | |

| Number of turnstiles with automatic control on entrances | 2,374 |

| Number of stations with escalators | 125 |

| Number of escalators | 631 |

| — including Monorail stations | 18 |

| Longest escalator | 126 metres (413 ft) (Park Pobedy) |

| Total number of ventilation shafts | 393 |

| Number of local ventilation systems in use | 4,965 |

| Number of medical assistance points (2005) | 46 |

| Total length of all escalators | 65.4 kilometres (40.6 mi) |

| Rolling stock statistics | |

| Number of train maintenance depots | 16 |

| Total number of train runs per day | 9,915 |

| Average speed: | |

| — commercial | 41.71 kilometres per hour (25.92 mph) |

| — technical (2005) | 48.85 kilometres per hour (30.35 mph) |

| Total number of cars (average per day) | 4,428 |

| Cars in service (average per day) | 3,397 |

| Annual run of all cars | 722,100,000 kilometres (448,700,000 mi) |

| Average daily run of a car | 556.2 kilometres (345.6 mi) |

| Average passengers per car | 53 people |

| Timetable fulfillment | 99.96% |

| Minimum average interval | 90 sec |

| Staff statistics | |

| Total number of employees | 34,792 people |

| — males | 18,291 people |

| — females | 16,448 people |

Notable incidents

1977 bombing

On 8 January 1977, a bomb was reported to have killed 7 and seriously injured 33. It went off in a crowded train between Izmaylovskaya and Pervomayskaya stations.[43] Three Armenians were later arrested, charged and executed in connection with the incident.[44]

1981 station fires

In June 1981, seven bodies were seen being removed from the Oktyabrskaya station during a fire there. A fire was also reported at Prospekt Mira station about that time.[45]

1982 escalator accident

A fatal accident occurred on 17 February 1982 due to an escalator collapse at the Aviamotornaya station on the Kalininskaya Line. Eight people were killed and 30 injured due to a pileup caused by faulty emergency brakes.[46]

2000 bombings

On 8 August 2000, a strong blast in a Metro underpass at Pushkinskaya metro station in the center of Moscow claimed the lives of 12, with 150 injured. A homemade bomb equivalent to 800 grams of TNT had been left in a bag near a kiosk.[47]

2004 bombings

On 6 February 2004, an explosion wrecked a train between the Avtozavodskaya and Paveletskaya stations on the Zamoskvoretskaya Line, killing 41 and wounding over 100.[48] Chechen terrorists were blamed. A later investigation concluded that a Karachay-Cherkessian resident (an Islamic militant) had carried out a suicide bombing. The same group organized another attack on 31 August 2004, killing 10 and injuring more than 50 others.

2005 Moscow blackout

On 25 May 2005, a citywide blackout halted operation on some lines. The following lines, however, continued operations: Sokolnicheskaya, Zamoskvoretskaya from Avtozavodskaya to Rechnoy Vokzal, Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya, Filyovskaya, Koltsevaya, Kaluzhsko-Rizhskaya from Bitsevskiy Park to Oktyabrskaya-Radialnaya and from Prospekt Mira-Radialnaya to Medvedkovo, Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya, Kalininskaya, Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya from Serpukhovskaya to Altufyevo and Lyublinskaya from Chkalovskaya to Dubrovka.[49] There was no service on the Kakhovskaya and Butovskaya lines. The blackout severely affected the Zamoskvoretskaya and Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya lines, where initially all service was disrupted because of trains halted in tunnels in the southern part of city (most affected by the blackout). Later, limited service resumed and passengers stranded in tunnels were evacuated. Some lines were only slightly impacted by the blackout, which mainly affected southern Moscow; the north, east and western parts of the city experienced little or no disruption.[49]

2006 billboard incident

On 19 March 2006 a construction pile from an unauthorized billboard installation was driven through a tunnel roof, hitting a train between the Sokol and Voikovskaya stations on the Zamoskvoretskaya Line. No injuries were reported.[50]

2010 bombing

On 29 March 2010, two bombs exploded on the Sokolnicheskaya Line, killing 40 and injuring 102 others. The first bomb went off at the Lubyanka station on the Sokolnicheskaya Line at 7:56, during the morning rush hour.[51] At least 26 were killed in the first explosion, of which 14 were in the rail car where it took place. A second explosion occurred at the Park Kultury station at 8:38, roughly forty minutes after the first one.[51] Fourteen people were killed in that blast. The Caucasus Emirate later claimed responsibility for the bombings.

2014 pile incident

On 25 January 2014, at 15:37 a construction pile from a Moscow Central Circle construction site was driven through a tunnel roof between Avtozavodskaya and Kolomenskaya stations on the Zamoskvoretskaya Line. The train operator applied emergency brakes, and the train did not crash into the pile. Passengers were evacuated from the tunnel, with no injures reported. The normal line operation resumed the same day at 20:00.

2014 derailment

On 15 July 2014, a train derailed between Park Pobedy and Slavyansky Bulvar on the Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Line, killing twenty four people and injuring dozens more.

In popular culture

The Moscow Metro is the central location and namesake for the Metro series, where during a nuclear war, Moscow's inhabitants are driven down into the Moscow Metro, which has been designed as a fallout shelter, with the various stations being turned into makeshift settlements.

In 2012, an art film was released about a catastrophe in the Moscow underground.[52]

See also

- List of Moscow metro stations

- Expansion timeline of the Moscow Metro

- List of metro systems

- Moscow Metro ridership statistics (in Russian)

- Metro dogs

- Trams in Moscow

- Metro 2033

Notes

References

- Метрополитен в цифрах [Metropolitan in figures] (in Russian). Moscow Metro. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "Top 8 places to visit in Moscow". Expat Guide to Russia | Expatica.

- "Московский метрополитен".

- "Lines and stations". Moscow Metro website. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- See this image as an example

- "Режим работы станций и вестибюлей". Moscow Metro. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Голоса в метро. Official blog of Moscow Metro (in Russian). 26 November 2010. Archived from the original on 24 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Metro.ru Original order on naming the Metro after Kaganovich. Retrieved Archived 10 July 2001 at Archive.today 19 October 2007

- http://www.pootergeek.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2008/08/gants_hill.jpg

- Lawrence, David (1994). Underground Architecture. Harrow: Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-160-0.

- Michael Robbins, "London Underground and Moscow Metro," Journal of Transport History, (1997) 18#1 pp 45-53.

- Gordon W. Morrell, "Redefining Intelligence and Intelligence-Gathering: The Industrial Intelligence Centre and the Metro-Vickers Affair, Moscow 1933," Intelligence and National Security (1994) 9#3 pp 520-533.

- Sachak (date unknown). История создания Московского метро (History of Moscow Metro) (in Russian)

- Jenks, Andrew (October 2000). "A Metro on the Mount: The Underground as a Church of Soviet Civilization". Technology and Culture. 41 (4): 697–724. doi:10.1353/tech.2000.0160. JSTOR 2517594.

- Moscow Metro / Moscow Metro / General Information / Key Performance Indicators Archived 10 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Engl.mosmetro.ru. Retrieved on 17 August 2013.

- First Metro map. Retrieved from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Cooke, Catherine (1997). "Beauty as a Route to 'the Radiant Future': Responses of Soviet Architecture". Journal of Design History. Design, Stalin and the Thaw. 10 (2): 137–160. doi:10.1093/jdh/10.2.137. JSTOR 1316129.

- Bowlt, John E. (2002). "Stalin as Isis and Ra: Socialist Realism and the Art of Design". The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts. Design, Culture, Identity: The Wolfsonian Collection. 24: 34–63. doi:10.2307/1504182. JSTOR 1504182.

- Damsky, Abram (Summer 1987). "Lamps and Architecture 1930–1950". The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts. 5 (Russian/Soviet Theme): 90–111. doi:10.2307/1503938. JSTOR 1503938.

- O'Mahoney, Mike (January 2003). "Archaeological Fantasies: Constructing History on the Moscow Metro". The Modern Language Review. 98 (1): 138–150. doi:10.2307/3738180. JSTOR 3738180.

- Isabel Wünsche, "Homo Sovieticus: The Athletic Motif in the Design of the Dynamo Metro Station," Studies in the Decorative Arts (2000) 7#2 pp 65-90

- Andrew Jenks, "A Metro on the Mount," Technology & Culture (2000) 41#4 pp 697-723p

- Voyce, Arthur (January 1956). "Soviet Art and Architecture: Recent Developments". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Russia Since Stalin: Old Trends and New Problems. 303: 104–115. doi:10.1177/000271625630300110. JSTOR 1032295.

- Бесплатные пересадки Московского центрального кольца, MCC official Facebook group

- "У московского метро нет логотипа". ADME. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014.

- "Проект DesignContest проводит конкурс на новый логотип столичного метро". Алиса По. The Vilarge. 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Moscow Metro 2014". DesignContest. 2013.

- "Moscow Metro: the World's First Major Transport System to operate fully contactless with NXP's MIFARE Technology". NXP Semiconductors. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- "Table of tariffs" (in Russian). City of Moscow.

- "Безналичная система оплаты проезда". Moscow metro. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "Troika official site". City of Moscow. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- "30 squats gets you a subway ride in Russia". Mother Nature Network. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- Московское метро ввело оплату с мобильного телефона. BBC Русская служба (in Russian). 4 September 2015.

- Moscow Metro / Public Relations Department / News Archived 7 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Engl.mosmetro.ru (24 November 2010). Retrieved on 2013-08-17.

- "На сколько в 2016 году подорожает проезд в московском метро?".

- "Крокус" сдал "частную" станцию метро. bn.ru (in Russian).

- "Третий пересадочный контур метро разгрузит Кольцевую ветку на 20%". RIA Novosti. 10 March 2009.

- "Власти Москвы утвердили план развития столичного метро с 2012 года". RIA Novosti. 22 March 2010.

- "Two new TBM have started in Moscow". Rossiyskaya Gazeta. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- Google (7 May 2016). "Under construction Moscow Metro on the map" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- "Moscow Metro 2 – The dark legend of Moscow". Moscow Russia Insider's Guide. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- "Метро-2".

- "Terrorism: an appetite for killing for political purposes". Pravda.ru. 11 September 2006. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- Взрыв на Арбатско-Покровской линии в 1977г.. metro.molot.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- "7 Die in Moscow Subway Fire". The New York Times. UPI. 12 June 1981. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- Авария эскалатора на станции "Авиамоторная". metro.molot.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- "In pictures: Moscow's bomb horror". news.bbc.co.uk. BBC News.

- Взрыв на Замоскворецкой линии. metro.molot.ru (in Russian).

- Grashchenkov, Ilya (25 May 2005). "Archived copy" Как работает московское метро. Список закрытых станций (in Russian). Yтро.ru. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Moscow Metro Tunnel Collapses on Train; Nobody Hurt Archived 6 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "38 killed in Moscow metro suicide attacks". RTÉ. 29 March 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- "КиноПоиск.ru". www.kinopoisk.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 27 July 2017.

Further reading

- Winchester, Clarence, ed. (1936), "Moscow's underground", Railway Wonders of the World, pp. 894–899 illustrated contemporary description of the Moscow underground

- Sergey Kuznetsov/ Alexander Zmeul/ Erken Kagarov: Hidden Urbanism: Architecture and Design of the Moscow Metro 1935-2015. Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3869224121.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Official website

- List of famous Moscow Metro stations

- Geographically precise Moscow Metro map (in Russian)