Railway electrification system

A railway electrification system supplies electric power to railway trains and trams without an on-board prime mover or local fuel supply. Electric railways use either electric locomotives (hauling passengers or freight in separate cars), electric multiple units (passenger cars with their own motors) or both. Electricity is typically generated in large and relatively efficient generating stations, transmitted to the railway network and distributed to the trains. Some electric railways have their own dedicated generating stations and transmission lines, but most purchase power from an electric utility. The railway usually provides its own distribution lines, switches, and transformers.

Power is supplied to moving trains with a (nearly) continuous conductor running along the track that usually takes one of two forms: an overhead line, suspended from poles or towers along the track or from structure or tunnel ceilings, or a third rail mounted at track level and contacted by a sliding "pickup shoe". Both overhead wire and third-rail systems usually use the running rails as the return conductor, but some systems use a separate fourth rail for this purpose.

In comparison to the principal alternative, the diesel engine, electric railways offer substantially better energy efficiency, lower emissions, and lower operating costs. Electric locomotives are also usually quieter, more powerful, and more responsive and reliable than diesels. They have no local emissions, an important advantage in tunnels and urban areas. Some electric traction systems provide regenerative braking that turns the train's kinetic energy back into electricity and returns it to the supply system to be used by other trains or the general utility grid. While diesel locomotives burn petroleum, electricity can be generated from diverse sources, including renewable energy.[1]

Disadvantages of electric traction include: high capital costs that may be uneconomic on lightly trafficked routes, a relative lack of flexibility (since electric trains need third rails or overhead wires), and a vulnerability to power interruptions.[1] Electro-diesel locomotives and Electro-diesel multiple units mitigate these problems somewhat as they are capable of running on diesel power during an outage or on non-electrified routes.

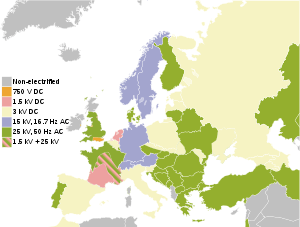

Different regions may use different supply voltages and frequencies, complicating through service and requiring greater complexity of locomotive power. The limited clearances available under overhead lines may preclude efficient double-stack container service.[1]

Railway electrification has constantly increased in the past decades, and as of 2012, electrified tracks account for nearly one third of total tracks globally.[2]

Classification

Electrification systems are classified by three main parameters:

- Voltage

- Current

- Direct current (DC)

- Alternating current (AC)

- Contact system

- Third rail

- Fourth rail

- Overhead lines (catenary)

- Overhead lines plus linear motor

Selection of an electrification system is based on economics of energy supply, maintenance, and capital cost compared to the revenue obtained for freight and passenger traffic. Different systems are used for urban and intercity areas; some electric locomotives can switch to different supply voltages to allow flexibility in operation.

Standardised voltages

Six of the most commonly used voltages have been selected for European and international standardisation. Some of these are independent of the contact system used, so that, for example, 750 V DC may be used with either third rail or overhead lines.

There are many other voltage systems used for railway electrification systems around the world, and the list of railway electrification systems covers both standard voltage and non-standard voltage systems.

The permissible range of voltages allowed for the standardised voltages is as stated in standards BS EN 50163[3] and IEC 60850.[4] These take into account the number of trains drawing current and their distance from the substation.

| Electrification system | Voltage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. non-permanent | Min. permanent | Nominal | Max. permanent | Max. non-permanent | |

| 600 V DC | 400 V | 400 V | 600 V | 720 V | 800 V |

| 750 V DC | 500 V | 500 V | 750 V | 900 V | 1,000 V |

| 1,500 V DC | 1,000 V | 1,000 V | 1,500 V | 1,800 V | 1,950 V |

| 3 kV DC | 2 kV | 2 kV | 3 kV | 3.6 kV | 3.9 kV |

| 15 kV AC, 16.7 Hz | 11 kV | 12 kV | 15 kV | 17.25 kV | 18 kV |

| 25 kV AC, 50 Hz (EN 50163) and 60 Hz (IEC 60850) |

17.5 kV | 19 kV | 25 kV | 27.5 kV | 29 kV |

Direct current

Increasing availability of high-voltage semiconductors may allow the use of higher and more efficient DC voltages that heretofore have only been practical with AC.[5]

Overhead systems

1,500 V DC is used in Japan, Indonesia, Hong Kong (parts), Republic of Ireland, Australia (parts), France (also using 25 kV 50 Hz AC), New Zealand (Wellington), Singapore (on the North East MRT Line), the United States (Chicago area on the Metra Electric district and the South Shore Line interurban line and Link light rail in Seattle, Washington). In Slovakia, there are two narrow-gauge lines in the High Tatras (one a cog railway). In the Netherlands it is used on the main system, alongside 25 kV on the HSL-Zuid and Betuwelijn, and 3000 V south of Maastricht. In Portugal, it is used in the Cascais Line and in Denmark on the suburban S-train system (1650 V DC).

In the United Kingdom, 1,500 V DC was used in 1954 for the Woodhead trans-Pennine route (now closed); the system used regenerative braking, allowing for transfer of energy between climbing and descending trains on the steep approaches to the tunnel. The system was also used for suburban electrification in East London and Manchester, now converted to 25 kV AC. It is now only used for the Tyne and Wear Metro. In India, 1,500 V DC was the first electrification system launched in 1925 in Mumbai area. Between 2012 and 2016, the electrification was converted to 25 kV 50 Hz AC which is the countrywide system.

3 kV DC is used in Belgium, Italy, Spain, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Chile, the northern portion of the Czech Republic, the former republics of the Soviet Union, and the Netherlands. It was formerly used by the Milwaukee Road from Harlowton, Montana, to Seattle, across the Continental Divide and including extensive branch and loop lines in Montana, and by the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (now New Jersey Transit, converted to 25 kV AC) in the United States, and the Kolkata suburban railway (Bardhaman Main Line) in India, before it was converted to 25 kV 50 Hz AC.

DC voltages between 600 V and 800 V are used by most tramways (streetcars), trolleybus networks and underground (subway) systems.

Overhead systems with linear motor

Third rail

Most electrification systems use overhead wires, but third rail is an option up to 1,500 V, as is the case with Shenzhen Metro Line 3. Third rail systems exclusively use DC distribution. The use of AC is not feasible because the dimensions of a third rail are physically very large compared with the skin depth that the alternating current penetrates to 0.3 millimetres or 0.012 inches in a steel rail. This effect makes the resistance per unit length unacceptably high compared with the use of DC.[6] Third rail is more compact than overhead wires and can be used in smaller-diameter tunnels, an important factor for subway systems.

Fourth rail

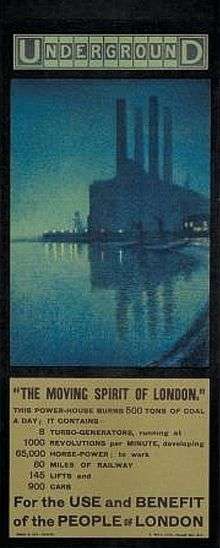

The London Underground in England is one of the few networks that uses a four-rail system. The additional rail carries the electrical return that, on third rail and overhead networks, is provided by the running rails. On the London Underground, a top-contact third rail is beside the track, energized at +420 V DC, and a top-contact fourth rail is located centrally between the running rails at −210 V DC, which combine to provide a traction voltage of 630 V DC. The same system was used for Milan's earliest underground line, Milan Metro's line 1, whose more recent lines use an overhead catenary or a third rail.

The key advantage of the four-rail system is that neither running rail carries any current. This scheme was introduced because of the problems of return currents, intended to be carried by the earthed (grounded) running rail, flowing through the iron tunnel linings instead. This can cause electrolytic damage and even arcing if the tunnel segments are not electrically bonded together. The problem was exacerbated because the return current also had a tendency to flow through nearby iron pipes forming the water and gas mains. Some of these, particularly Victorian mains that predated London's underground railways, were not constructed to carry currents and had no adequate electrical bonding between pipe segments. The four-rail system solves the problem. Although the supply has an artificially created earth point, this connection is derived by using resistors which ensures that stray earth currents are kept to manageable levels. Power-only rails can be mounted on strongly insulating ceramic chairs to minimise current leak, but this is not possible for running rails which have to be seated on stronger metal chairs to carry the weight of trains. However, elastomeric rubber pads placed between the rails and chairs can now solve part of the problem by insulating the running rails from the current return should there be a leakage through the running rails.

Linear motor

a number of linear motor systems systems run on conventional metal rails and pull power from a third rail, but are propelled by a linear induction motor that provides traction by pulling on a "fourth rail" placed between the running rails. Bombardier, Kawasaki Heavy Industries and CRRC manufacture linear motor systems. Guangzhou Metro operates the longest such system with over 130 km (81 mi) of route along Line 4, Line 5 and Line 6.

In the case of Scarborough Line 3, the third and fourth rails are outside the track and the fifth rail is an aluminum slab between the running rails.

Rubber-tyred systems

A few lines of the Paris Métro in France operate on a four-rail power system. The trains move on rubber tyres which roll on a pair of narrow roll ways made of steel and, in some places, of concrete. Since the tyres do not conduct the return current, the two guide bars provided outside the running 'roll ways' become, in a sense, a third and fourth rail which each provide 750 V DC, so at least electrically it is a four-rail system. Each wheel set of a powered bogie carries one traction motor. A side sliding (side running) contact shoe picks up the current from the vertical face of each guide bar. The return of each traction motor, as well as each wagon, is effected by one contact shoe each that slide on top of each one of the running rails. This and all other rubber-tyred metros that have a 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge track between the roll ways operate in the same manner.[7][8]

Alternating current

Railways and electrical utilities use AC for the same reason: to use transformers, which require AC, to produce higher voltages. The higher the voltage, the lower the current for the same power, which reduces line loss, thus allowing higher power to be delivered.

Because alternating current is used with high voltages, this method of electrification is only used on overhead lines, never on third rails. Inside the locomotive, a transformer steps the voltage down for use by the traction motors and auxiliary loads.

An early advantage of AC is that the power-wasting resistors used in DC locomotives for speed control were not needed in an AC locomotive: multiple taps on the transformer can supply a range of voltages. Separate low-voltage transformer windings supply lighting and the motors driving auxiliary machinery. More recently, the development of very high power semiconductors has caused the classic DC motor to be largely replaced with the three-phase induction motor fed by a variable frequency drive, a special inverter that varies both frequency and voltage to control motor speed. These drives can run equally well on DC or AC of any frequency, and many modern electric locomotives are designed to handle different supply voltages and frequencies to simplify cross-border operation.

Low-frequency alternating current

Five European countries, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Norway and Sweden, have standardized on 15 kV 16 2⁄3 Hz (the 50 Hz mains frequency divided by three) single-phase AC. On 16 October 1995, Germany, Austria and Switzerland changed from 16 2⁄3 Hz to 16.7 Hz which is no longer exactly one-third of the grid frequency. This solved overheating problems with the rotary converters used to generate some of this power from the grid supply.[9]

In the UK, the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway pioneered overhead electrification of its suburban lines in London, London Bridge to Victoria being opened to traffic on 1 December 1909. Victoria to Crystal Palace via Balham and West Norwood opened in May 1911. Peckham Rye to West Norwood opened in June 1912. Further extensions were not made owing to the First World War. Two lines opened in 1925 under the Southern Railway serving Coulsdon North and Sutton railway station.[10][11] The lines were electrified at 6.7 kV 25 Hz. It was announced in 1926 that all lines were to be converted to DC third rail and the last overhead electric service ran in September 1929.

Non-contact systems

It is possible to supply power to an electric train by inductive coupling. This allows the use of a high-voltage, insulated, conductor rail. Such a system was patented in 1894 by Nikola Tesla, U.S. Patent 514,972. It requires the use of high-frequency alternating current. Tesla did not specify a frequency but George Trinkaus[12] suggests that around 1,000 Hz would be likely.

Inductive coupling is widely used in low-power applications, such as re-chargeable electric toothbrushes and more recently, mobile telephones and wearable computing devices (inductive charging).

Energy efficiency

Electric versus diesel

Electric trains need not carry the weight of prime movers, transmission and fuel. This is partly offset by the weight of electrical equipment.

Regenerative braking returns power to the electrification system so that it may be used elsewhere, by other trains on the same system or returned to the general power grid. This is especially useful in mountainous areas where heavily loaded trains must descend long grades.

Central station electricity can often be generated with higher efficiency than a mobile engine/generator. While the efficiency of power plant generation and diesel locomotive generation are roughly the same in the nominal regime,[13] diesel motors decrease in efficiency in non-nominal regimes at low power [14] while if an electric power plant needs to generate less power it will shut down its least efficient generators, thereby increasing efficiency. The electric train can save energy (as compared to diesel) by regenerative braking and by not needing to consume energy by idling as diesel locomotives do when stopped or coasting. However, electric rolling stock may run cooling blowers when stopped or coasting, thus consuming energy.

Large fossil fuel power stations operate at high efficiency,[15][16] and can be used for district heating or to produce district cooling, leading to a higher total efficiency.

AC versus DC for mainlines

The majority of modern electrification systems take AC energy from a power grid that is delivered to a locomotive, and within the locomotive, transformed and rectified to a lower DC voltage in preparation for use by traction motors. These motors may either be DC motors which directly use the DC or they may be 3-phase AC motors which require further conversion of the DC to 3-phase AC (using power electronics). Thus both systems are faced with the same task: converting and transporting high-voltage AC from the power grid to low-voltage DC in the locomotive. The difference between AC and DC electrification systems lies in where the AC is converted to DC: at the substation or on the train. Energy efficiency and infrastructure costs determine which of these is used on a network, although this is often fixed due to pre-existing electrification systems.

Both the transmission and conversion of electric energy involve losses: ohmic losses in wires and power electronics, magnetic field losses in transformers and smoothing reactors (inductors).[17] Power conversion for a DC system takes place mainly in a railway substation where large, heavy, and more efficient hardware can be used as compared to an AC system where conversion takes place aboard the locomotive where space is limited and losses are significantly higher.[18] However, the higher voltages used in many AC electrification systems reduces transmission losses over longer distances, allowing for fewer substations or more powerful locomotives to be used. Also, the energy used to blow air to cool transformers, power electronics (including rectifiers), and other conversion hardware must be accounted for.

Comparison with diesel traction

Electric locomotives may easily be constructed with greater power output than most diesel locomotives. For passenger operation it is possible to provide enough power with diesel engines (see e.g. 'ICE TD') but, at higher speeds, this proves costly and impractical. Therefore, almost all high speed trains are electric. The high power of electric locomotives also gives them the ability to pull freight at higher speed over gradients; in mixed traffic conditions this increases capacity when the time between trains can be decreased. The higher power of electric locomotives and an electrification can also be a cheaper alternative to a new and less steep railway if trains weights are to be increased on a system.

On the other hand, electrification may not be suitable for lines with low frequency of traffic, because lower running cost of trains may be outweighed by the high cost of the electrification infrastructure. Therefore, most long-distance lines in developing or sparsely populated countries are not electrified due to relatively low frequency of trains.

Maintenance costs of the lines may be increased by electrification, but many systems claim lower costs due to reduced wear-and-tear from lighter rolling stock.[19] There are some additional maintenance costs associated with the electrical equipment around the track, such as power sub-stations and the catenary wire itself, but, if there is sufficient traffic, the reduced track and especially the lower engine maintenance and running costs exceed the costs of this maintenance significantly.

Network effects are a large factor with electrification. When converting lines to electric, the connections with other lines must be considered. Some electrifications have subsequently been removed because of the through traffic to non-electrified lines. If through traffic is to have any benefit, time-consuming engine switches must occur to make such connections or expensive dual mode engines must be used. This is mostly an issue for long-distance trips, but many lines come to be dominated by through traffic from long-haul freight trains (usually running coal, ore, or containers to or from ports). In theory, these trains could enjoy dramatic savings through electrification, but it can be too costly to extend electrification to isolated areas, and unless an entire network is electrified, companies often find that they need to continue use of diesel trains even if sections are electrified. The increasing demand for container traffic which is more efficient when utilizing the double-stack car also has network effect issues with existing electrifications due to insufficient clearance of overhead electrical lines for these trains, but electrification can be built or modified to have sufficient clearance, at additional cost.

A problem specifically related to electrified lines are gaps in the electrification. Electric vehicles, especially locomotives, lose power when traversing gaps in the supply, such as phase change gaps in overhead systems, and gaps over points in third rail systems. These become a nuisance, if the locomotive stops with its collector on a dead gap, in which case there is no power to restart. Power gaps can be overcome by on-board batteries or motor-flywheel-generator systems. In 2014, progress is being made in the use of large capacitors to power electric vehicles between stations, and so avoid the need for overhead wires between those stations.[20]

Advantages

- No exposure to passengers to exhaust from the locomotive

- Lower cost of building, running and maintaining locomotives and multiple units

- Higher power-to-weight ratio (no onboard fuel tanks), resulting in

- Fewer locomotives

- Faster acceleration

- Higher practical limit of power

- Higher limit of speed

- Less noise pollution (quieter operation)

- Faster acceleration clears lines more quickly to run more trains on the track in urban rail uses

- Reduced power loss at higher altitudes (for power loss see Diesel engine)

- Independence of running costs from fluctuating fuel prices

- Service to underground stations where diesel trains cannot operate for safety reasons

- Reduced environmental pollution, especially in highly populated urban areas, even if electricity is produced by fossil fuels

- Easily accommodates kinetic energy brake reclaim using supercapacitors

- More comfortable ride on multiple units as trains have no underfloor diesel engines

- Somewhat higher energy efficiency [21] in part due to regenerative braking and less power lost when "idling"

- More flexible primary energy source: can use coal, nuclear, hydro or wind as the primary energy source instead of oil

Disadvantages

- Electrification cost: electrification requires an entire new infrastructure to be built around the existing tracks at a significant cost. Costs are especially high when tunnels, bridges and other obstructions have to be altered for clearance. Another aspect that can raise the cost of electrification are the alterations or upgrades to railway signalling needed for new traffic characteristics, and to protect signalling circuitry and track circuits from interference by traction current. Electrification may require line closures while the new equipment is being installed.

- Appearance: the overhead line structures and cabling can have a significant landscape impact compared with a non-electrified or third rail electrified line that has only occasional signalling equipment above ground level.

- Fragility and vulnerability: overhead electrification systems can suffer severe disruption due to minor mechanical faults or the effects of high winds causing the pantograph of a moving train to become entangled with the catenary, ripping the wires from their supports. The damage is often not limited to the supply to one track, but extends to those for adjacent tracks as well, causing the entire route to be blocked for a considerable time. Third-rail systems can suffer disruption in cold weather due to ice forming on the conductor rail.[23]

- Theft: the high scrap value of copper and the unguarded, remote installations make overhead cables an attractive target for scrap metal thieves.[24] Attempts at theft of live 25 kV cables may end in the thief's death from electrocution.[25] In the UK, cable theft is claimed to be one of the biggest sources of delay and disruption to train services — though this normally relates to signalling cable, which is equally problematic for diesel lines.[26]

- Birds may perch on parts with different charges, and animals may also touch the electrification system. Dead animals attract foxes or other predators,[27] bringing risk of collision with trains.

- In most of the world's railway networks, the height clearance of overhead electrical lines is not sufficient for a double-stack container car or other unusually tall loads. It is extremely costly to upgrade electrified lines to the correct clearances (21 ft 8 in or 6.60 m) to take double-stacked container trains.

World electrification

In 2006, 240,000 km (150,000 mi) (25% by length) of the world rail network was electrified and 50% of all rail transport was carried by electric traction.

Since 2012,[28] China has the largest electrified railway length with over 100,000 km (62,000 mi) electrified railway in 2020 or just over 70% of the network.[29] Trailing behind China were Russia 43,300 km (26,900 mi), India 39,866 km (24,772 mi),[30] Germany 21,000 km (13,000 mi), Japan 17,000 km (11,000 mi), and France 15,200 km (9,400 mi).

Sparks effect

Newly electrified lines often show a "sparks effect", whereby electrification in passenger rail systems leads to significant jumps in patronage / revenue.[31] The reasons may include electric trains being seen as more modern and attractive to ride,[32][33] faster and smoother service,[31] and the fact that electrification often goes hand in hand with a general infrastructure and rolling stock overhaul / replacement, which leads to better service quality (in a way that theoretically could also be achieved by doing similar upgrades yet without electrification). Whatever the causes of the sparks effect, it is well established for numerous routes that have electrified over decades.[31][32]

See also

- Battery electric multiple unit

- Battery locomotive

- Conduit current collection

- Current collector

- Dual electrification

- Electromote

- Ground-level power supply

- History of the electric locomotive

- Initial Electrification Experiments NY NH HR

- List of railway electrification systems

- List of tram systems by gauge and electrification

- Multi-system (rail)

- Overhead conductor rails

- Railroad electrification in the United States

- Stud contact system

- Traction current pylon

- Traction powerstation

- Traction substation

References

- P. M. Kalla-Bishop, Future Railways and Guided Transport, IPC Transport Press Ltd. 1972, pp. 8-33

- "Railway Handbook 2015" (PDF). International Energy Agency. p. 18. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- EN 50163: Railway applications. Supply voltages of traction systems (2007)

- IEC 60850: Railway applications – Supply voltages of traction systems, 3rd edition (2007)

- P. Leandes and S. Ostlund. "A concept for an HVDC traction system" in "International conference on main line railway electrification", Hessington, England, September 1989 (Suggests 30 kV). Glomez-Exposito A., Mauricio J.M., Maza-Ortega J.M. "VSC-based MVDC Railway Electrification System" IEEE transactions on power delivery, v.29, no.1, Feb.2014. (suggests 24 kV).

- Donald G. Fink, H. Wayne Beatty Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers 11th Edition, McGraw Hill, 1978 table 18-21. See also Gomez-Exposito p.424, Fig.3

- "[MétroPole] De la centrale électrique au rail de traction". 10 August 2004. Archived from the original on 10 August 2004.

- Dery, Bernard. "Truck (bogie) - Visual Dictionary". www.infovisual.info.

- Linder, C. (2002). Umstellung der Sollfrequenz im zentralen Bahnstromnetz von 16 2/3 Hz auf 16,70 Hz [Switching the frequency in train electric power supply network from 16 2/3 Hz to 16,70 Hz]. Elektrische Bahnen (in German). Oldenbourg-Industrieverlag. ISSN 0013-5437.

- History of Southern Electrification Part 1

- History of Southern Electrification Part 2

- Trinkaus, George, Tesla, the lost inventions, pp 28–29, High Voltage Press, Portland, OR, 1988

- It turns out that the efficiency of electricity generation by a modern diesel locomotive is roughly the same as the typical U.S. fossil-fuel power plant. The heat rate of central power plants in 2012 was about 9.5k BTU/kwh per the Monthly Energy Review of the U.S. Energy Information Administration which corresponds to an efficiency of 36%. Diesel motors for locomotives have an efficiency of about 40% (see Brake specific fuel consumption, Дробинский p. 65 and Иванова p.20.). But there are reductions needed in both efficiencies needed to make a comparison. First, one must degrade the efficiency of central power plants by the transmission losses to get the electricity to the locomotive. Another correction is due to the fact that efficiency for the Russian diesel is based on the lower heat of combustion of fuel while power plants in the U.S. use the higher heat of combustion (see Heat of combustion. Still another correction is that the diesel's reported efficiency neglects the fan energy used for engine cooling radiators. See Дробинский p. 65 and Иванова p.20 (who estimates the on-board electricity generator as 96.5% efficient). The result of all the above is that modern diesel engines and central power plants are both about 33% efficient at generating electricity (in the nominal regime).

- Хомич А.З. Тупицын О.И., Симсон А.Э. "Экономия топлива и теплотехническая модернизация тепловозов" (Fuel economy and the thermodynamic modernization of diesel locomotives) - Москва: Транспорт, 1975 - 264 pp. See Brake specific fuel consumption curves on p. 202 and charts of times spent in non-nominal regimes on pp. 10-12

- Wang, Ucilia (25 May 2011). "Gigaom GE to Crank Up Gas Power Plants Like Jet Engines". Gigaom.com. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Archived 24 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- See Винокуров p.95+ Ch. 4: Потери и коэффициент полизного действия; нагреванние и охлаждение электрических машин и трансформаторов" (Losses and efficiency; heating and cooling of electrical machinery and transformers) magnetic losses pp.96-7, ohmic losses pp.97-9

- Сидоров 1988 pp. 103-4, Сидоров 1980 pp. 122-3

- "UK Network Rail electrification strategy report" Table 3.3, page 31. Retrieved on 4 May 2010

- Railway Gazette International Oct 2014.

- Per Railway electrification in the Soviet Union#Energy-Efficiency it was claimed that after the mid 1970s electrics used about 25% less fuel per ton-km than diesels. However, part of this savings may be due to less stopping of electrics to let opposing trains pass since diesels operated predominately on single-track lines, often with moderately heavy traffic.

- AAR Plate H

- "Committee Meeting - Royal Meteorological Society - Spring 2009" (PDF). Royal Meteorological Society (rmets.org). Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- "Network Rail - Cable Theft". Network Rail (www.networkrail.co.uk). Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- "Police probe cable theft death link". ITV News. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- Sarah Saunders (28 June 2012). "Body discovery linked to rail cables theft". ITV News. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- Nachmann, Lars. "Tiere & Pflanzen Vögel Gefährdungen Stromtod Mehr aus dieser Rubrik Vorlesen Die tödliche Gefahr". Naturschutzbund (in German). Berlin, Germany. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- See "Peoples Daily Online" (in English, newspaper) 5 December 2012 China's electric railway mileage exceeds 48,000 km

- "2019 年铁道统计公报" (PDF).

- "Ministry of Railways (Railway Board)". www.indianrailways.gov.in.

- "Start Slow With Bullet Trains". Miller-McCune. 2 May 2011. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- "Cumbernauld may be on track for railway line electrification". Cumbernauld News. 14 January 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- "Electric Idea". Bromsgrove Advertiser. 8 January 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

Sources

English

- Moody, G T (1960). "Part One". Southern Electric (3rd ed.). London: Ian Allan Ltd.

- Gomez-Exposito A., Mauricio J.M., Maza-Ortega J.M. "VSC-based MVDC Railway Electrification System" IEEE transactions on power delivery, v.29, no.1, Feb.2014 pp. 422–431. (suggests 24 kV DC)

- (Jane's) Urban Transit Systems

- Hammond, John Winthrop (2011) [1941]. Men and volts; the story of General Electric. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.; London, U.K.: General Electric Company; J. B. Lippincott & Co.; Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-258-03284-5 – via Internet archive.

He was to produce the first motor that operated without gears of any sort, having its armature direct-connected to the car axle.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Kaempffert, Waldemar Bernhard, Editor; Martin, T. Comerford (1924). A Popular History of American Invention. 1. London, U.K.; New York, NY, U.S.A.: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 11 March 2017 – via Internet archive.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malone, Dumas (1928). Sidney Howe Short. Dictionary of American Biography. 17. London, U.K.; New York, NY, U.S.A.: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 31 May 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Russian

- Винокуров В.А., Попов Д.А. "Электрические машины железно-дорожного транспорта" (Electrical machinery of railroad transportation), Москва, Транспорт, 1986. ISBN 5-88998-425-X, 520 pp.

- Дмитриев, В.А., "Народнохозяйственная эффективность электрификации железных дорог и применения тепловозной тяги" (National economic effectiveness of railway electrification and application of diesel traction), Москва, Транспорт 1976.

- Дробинский В.А., Егунов П.М. "Как устроен и работает тепловоз" (How the diesel locomotive works) 3rd ed. Moscow, Транспорт, 1980.

- Иванова В.Н. (ed.) "Конструкция и динамика тепловозов" (Construction and dynamics of the diesel locomotive). Москва, Транспорт, 1968 (textbook).

- Калинин, В.К. "Электровозы и электропоезда" (Electric locomotives and electric train sets) Москва, Транспорт, 1991 ISBN 978-5-277-01046-4

- Мирошниченко, Р.И., "Режимы работы электрифицированных участков" (Regimes of operation of electrified sections [of railways]), Москва, Транспорт, 1982.

- Перцовский, Л. М.; "Энергетическая эффективность электрической тяги" (Energy efficiency of electric traction), Железнодорожный транспорт (magazine), #12, 1974 p. 39+

- Плакс, А.В. & Пупынин, В. Н., "Электрические железные дороги" (Electric Railways), Москва "Транспорт" 1993.

- Сидоров Н.И., Сидорожа Н.Н. "Как устроен и работает электровоз" (How the electric locomotive works) Москва, Транспорт, 1988 (5th ed.) - 233 pp, ISBN 978-5-277-00191-2. 1980 (4th ed.).

- Хомич А.З. Тупицын О.И., Симсон А.Э. "Экономия топлива и теплотехническая модернизация тепловозов" (Fuel economy and the thermodynamic modernization of diesel locomotives) - Москва: Транспорт, 1975 - 264 pp.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Electrically-powered rail transport. |