Mars 2020

Mars 2020 is a Mars rover mission by NASA's Mars Exploration Program that includes the Perseverance rover with a planned launch on 22 July 2020 at 13:35 UTC,[1] and touch down in Jezero crater on Mars on 18 February 2021.[2][3] It will investigate an astrobiologically relevant ancient environment on Mars and investigate its surface geological processes and history, including the assessment of its past habitability, the possibility of past life on Mars, and the potential for preservation of biosignatures within accessible geological materials.[4][5] It will cache sample containers along its route for a potential future Mars sample-return mission.[5][6][7] The Mars 2020 mission was announced by NASA on 4 December 2012 at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.[8] The Perseverance rover's design is derived from the Curiosity rover, and will use many components already fabricated and tested, new scientific instruments and a core drill.[9] It will also carry a helicopter drone.

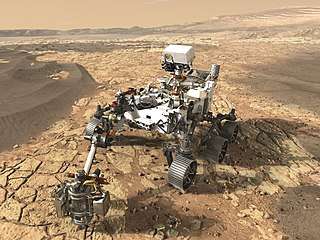

Computer-design drawing for NASA's Perseverance rover | |

| Mission type | Mars exploration |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA / JPL |

| Mission duration |

|

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft |

|

| Spacecraft type | Rover and drone |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 22 July 2020, 13:35 UTC |

| Rocket | Atlas V 541 (AV-088) |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral, SLC-41 |

| Contractor | United Launch Alliance |

| Mars rover | |

| Landing date | 18 February 2021 |

| Landing site | Jezero crater |

NASA (left) and JPL (right) insignias | |

Objectives

The mission will seek signs of habitable conditions on Mars in the ancient past, and will also search for evidence — or biosignatures — of past microbial life. The Perseverance rover is planned for launch in 2020 on an Atlas V-541,[8] and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory will manage the mission. The mission is part of NASA's Mars Exploration Program.[10][11][12][6] The Science Definition Team proposed that the rover collect and package as many as 31 samples of rock cores and surface soil for a later mission to bring back for definitive analysis on Earth. In 2015, they expanded the concept, planning to collect even more samples and distribute the tubes in small piles or caches across the surface of Mars.[13] In September 2013, NASA launched an Announcement of Opportunity for researchers to propose and develop the instruments needed, including the Sample Caching System.[14][15] The science instruments for the mission were selected in July 2014 after an open competition based on the scientific objectives set one year earlier.[16][17] The science conducted by the rover's instruments will provide the context needed for detailed analyses of the returned samples.[18] The chairman of the Science Definition Team stated that NASA does not presume that life ever existed on Mars, but given the recent Curiosity rover findings, past Martian life seems possible.[18]

The Perseverance rover will explore a site likely to have been habitable. It will seek signs of past life, set aside a returnable cache with the most compelling rock core and soil samples, and demonstrate technology needed for the future human and robotic exploration of Mars. A key mission requirement is that it must help prepare NASA for its long-term Mars sample-return mission and crewed mission efforts.[5][6][7] The rover will make measurements and technology demonstrations to help designers of a future human expedition understand any hazards posed by Martian dust, and will test technology to produce a small amount of pure oxygen (O

2) from Martian atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO

2).[19] Improved precision landing technology that enhances the scientific value of robotic missions also will be critical for eventual human exploration on the surface.[20] Based on input from the Science Definition Team, NASA defined the final objectives for the 2020 rover. Those become the basis for soliciting proposals to provide instruments for the rover's science payload in the spring of 2014.[19] The mission will also attempt to identify subsurface water, improve landing techniques, and characterize weather, dust, and other potential environmental conditions that could affect future astronauts living and working on Mars.[21]

A key mission requirement for this rover is that it must help prepare NASA for its Mars sample-return mission (MSR) campaign,[22][23][24] which is needed before any crewed mission takes place.[5][6][7] Such effort would require three additional vehicles: an orbiter, a fetch rover, and a Mars ascent vehicle (MAV).[25][26] Between 20 and 30 drilled samples will be collected and cached inside small tubes by the Perseverance rover,[27] and will be left on the surface of Mars for possible later retrieval by NASA in collaboration with ESA.[24][27] A "fetch rover" would retrieve the sample caches and deliver them to a Mars ascent vehicle (MAV). In July 2018, NASA contracted Airbus to produce a "fetch rover" concept study.[28] The MAV would launch from Mars and enter a 500 km orbit and rendezvous with the Next Mars Orbiter.[24] The sample container would be transferred to an Earth entry vehicle (EEV) which would bring it to Earth, enter the atmosphere under a parachute and hard-land for retrieval and analyses in specially designed safe laboratories.[23][24]

Spacecraft

Perseverance

.jpg)

.jpg)

Curiosity's engineering team were involved in the rover's design.[8][29] Engineers redesigned the Perseverance rover wheels to be more robust than Curiosity's wheels, which have sustained some damage.[30] The rover will have thicker, more durable aluminum wheels, with reduced width and a greater diameter (52.5 centimetres (20.7 in)) than Curiosity's 50 centimetres (20 in) wheels.[31][32] The aluminum wheels are covered with cleats for traction and curved titanium spokes for springy support.[33] The combination of the larger instrument suite, new Sampling and Caching System, and modified wheels makes Mars 2020 heavier than its predecessor, Curiosity,[32] by 17% (899 kg to 1050 kg). The rover will include a five-jointed robotic arm measuring 2.1 metres (6 ft 11 in) long. The arm will be used in combination with a turret to analyze geologic samples from the Martian surface.[34] A Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG), left over as a backup part for Curiosity during its construction, will power the rover.[8][35] The generator has a mass of 45 kilograms (99 lb) and uses 4.8 kilograms (11 lb) of plutonium dioxide as the source of steady supply of heat that is converted to electricity.[36] The electrical power generated is approximately 110 watts at launch with little decrease over the mission time.[36] Two lithium-ion rechargeable batteries are included to meet peak demands of rover activities when the demand temporarily exceeds the MMRTG's steady electrical output levels. The MMRTG offers a 14-year operational lifetime, and it was provided to NASA by the US Department of Energy.[36] Unlike solar panels, the MMRTG provides engineers with significant flexibility in operating the rover's instruments even at night and during dust storms, and through the winter season.[36]

Ingenuity

Ingenuity is a robotic helicopter that will test the technology to scout interesting targets for study on Mars, and help plan the best driving route for Perseverance.[37][38] The aircraft will be deployed from the rover's deck, and is expected to fly up to five times during its 30-day test campaign early in the mission.[39] Each flight will take no more than 3 minutes, at altitudes ranging from 3 m to 10 m above the ground,[40] but it could potentially cover a maximum distance of about 600 metres (2,000 ft) per flight.[41] It will use autonomous control and communicate with Perseverance directly after each landing. If it works as expected, NASA will be able to build on the design for future Mars missions.[40]

EDLS

The three major components of the Mars 2020 spacecraft are the cruise stage for travel between Earth and Mars; the Entry, Descent, and Landing System (EDLS) that includes the aeroshell, parachute, descent vehicle, and sky crane; and the Perseverance rover. The rover is based on the design of Curiosity.[8] While there are differences in scientific instruments and the engineering required to support them, the entire landing system (including the sky crane and heat shield) and rover chassis can essentially be recreated without any additional engineering or research. This reduces overall technical risk for the mission, while saving funds and time on development.[42] One of the upgrades is a guidance and control technique called "Terrain Relative Navigation" (TRN) to fine-tune steering in the final moments of landing.[43][44] This system will allow for a landing accuracy within 40 m (130 ft) and avoid obstacles.[45] This is a marked improvement from the Mars Science Laboratory mission that had an elliptical area of 7 by 20 kilometres (4.3 by 12.4 mi).[46] In October 2016, NASA reported using the Xombie rocket to test the Lander Vision System (LVS), as part of the Autonomous Descent and Ascent Powered-flight Testbed (ADAPT) experimental technologies, for the Mars 2020 mission landing, meant to increase the landing accuracy and avoid obstacle hazards.[47][48]

Mission

The rover mission and launch are estimated to cost about US$2.1 billion.[22] The mission's predecessor, the Mars Science Laboratory, cost $2.5 billion in total.[8] The availability of spare parts makes the new rover somewhat more affordable. The mission has a current launch date of 22 July 2020 at 13:35 UTC, where the positions of Earth and Mars are optimal for traveling to Mars. The rover is scheduled to land on Mars on 18 February 2021, with a planned surface mission of at least 1 Mars year (668 sols or 687 Earth days).[49][50][51] The mission will explore Jezero crater, which scientists speculate was a 250 m (820 ft) deep lake about 3.9 billion to 3.5 billion years ago.[2] Jezero today features a prominent river delta where water flowing through it deposited much sediment over the eons, which is "extremely good at preserving biosignatures".[2][3] The sediments in the delta likely include carbonates and hydrated silica, known to preserve microscopic fossils on Earth for billions of years.[52] Prior to the selection of Jezero, eight proposed landing sites for the mission were under consideration by September 2015; Columbia Hills in Gusev crater, Eberswalde crater, Holden crater, Jezero crater,[53][54] Mawrth Vallis, Northeastern Syrtis Major Planum, Nili Fossae, and Southwestern Melas Chasma.[55] A workshop was held on 8–10 February 2017 in Pasadena, California, to discuss these sites, with the goal of narrowing down the list to three sites for further consideration.[56] The three sites chosen were Jezero crater, Northeastern Syrtis Major Planum, and Columbia Hills.[57] Jezero crater was ultimately selected as the landing site in November 2018.[2]

Public outreach

To raise public awareness of the Mars 2020 mission, NASA undertook a "Send Your Name to Mars" campaign, through which people could send their names to Mars on a microchip stored aboard Perseverance. After registering their names, participants received a digital ticket with details of the mission's launch and destination. 10,932,295 names were submitted during the registration period.[58] In addition, NASA announced in June 2019 that a student naming contest for the rover will be held in the fall of 2019, voting on nine finalist names was held in January 2020,[59] and the winning name was announced on 5 March 2020.[60][61]

See also

References

- "Launch of NASA's Perseverance Mars rover delayed to July 22". Spaceflight Now. 24 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Chang, Kenneth (19 November 2018). "NASA Mars 2020 Rover Gets a Landing Site: A Crater That Contained a Lake - The rover will search the Jezero Crater and delta for the chemical building blocks of life and other signs of past microbes". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Wall, Mike (19 November 2018). "Jezero Crater or Bust! NASA Picks Landing Site for Mars 2020 Rover". Space.com. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Chang, Alicia (9 July 2013). "Panel: Next Mars rover should gather rocks, soil". Associated Press. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- Schulte, Mitch (20 December 2012). "Call for Letters of Application for Membership on the Science Definition Team for the 2020 Mars Science Rover" (PDF). NASA. NNH13ZDA003L.

- "Summary of the Final Report" (PDF). NASA / Mars Program Planning Group. 25 September 2012.

- Moskowitz, Clara (5 February 2013). "Scientists Offer Wary Support for NASA's New Mars Rover". Space.com. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- Harwood, William (4 December 2012). "NASA announces plans for new $1.5 billion Mars rover". CNET. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

Using spare parts and mission plans developed for NASA's Curiosity Mars rover, Ronnie Pickering says it can launch the rover in 2020 and stay within current budget guidelines.

- Amos, Jonathan (4 December 2012). "Nasa to send new rover to Mars in 2020". BBC News. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- "Program And Missions – 2020 Mission Plans". NASA. 2015.

- Mann, Adam (4 December 2012). "NASA Announces New Twin Rover for Curiosity Launching to Mars in 2020". Wired. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- Leone, Dan (3 October 2012). "Mars Planning Group Endorses Sample Return". SpaceNews.

- Davis, Jason (28 August 2017). "NASA considers kicking Mars sample return into high gear". The Planetary Society.

- "Announcement of Opportunity: Mars 2020 Investigations" (PDF). NASA. 24 September 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "Mars 2020 Mission: Instruments". NASA. 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- Brown, Dwayne (31 July 2014). "RELEASE 14-208 – NASA Announces Mars 2020 Rover Payload to Explore the Red Planet as Never Before". NASA. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- "Objectives – 2020 Mission Plans". mars.nasa.gov. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- "Science Team Outlines Goals for NASA's 2020 Mars Rover". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. 9 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- Klotz, Irene (21 November 2013). "Mars 2020 Rover To Include Test Device To Tap Planet's Atmosphere for Oxygen". SpaceNews. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Bergin, Chris (2 September 2014). "Curiosity EDL data to provide 2020 Mars Rover with super landing skills". NASASpaceFlight.com.

- "Mars 2020 Rover - Overview". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- Foust, Jeff (20 July 2016). "Mars 2020 rover mission to cost more than $2 billion". SpaceNews.

- Evans, Kim (13 October 2015). "NASA Eyes Sample-Return Capability for Post-2020 Mars Orbiter". Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Mattingly, Richard (March 2010). "Mission Concept Study: Planetary Science Decadal Survey - MSR Orbiter Mission (Including Mars Returned Sample Handling)" (PDF). NASA.

- Ross, D.; Russell, J.; Sutter, B. (March 2012). "Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV): Designing for high heritage and low risk". 2012 IEEE Aerospace Conference: 1–6. doi:10.1109/AERO.2012.6187296. ISBN 978-1-4577-0557-1.

- "Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV)" (PDF).

- How NASA's Next Mars Rover Will Hunt for Alien Life. Mike Wall, Space.com. 11 December 2019.

- Amos, Jonathan (6 July 2018). "Fetch rover! Robot to retrieve Mars rocks". BBC News. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Wall, Mike (4 December 2012). "NASA to Launch New Mars Rover in 2020". Space.com. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- Lakdawalla, Emily (19 August 2014). "Curiosity wheel damage: The problem and solutions". The Planetary Society Blogs. The Planetary Society. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- Gebhardt, Chris. "Mars 2020 rover receives upgraded eyesight for tricky skycrane landing". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Mars 2020 - Body: New Wheels for Mars 2020". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- "Mars 2020 Rover - Wheels". NASA. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- "Mars 2020 Rover's 7-Foot-Long Robotic Arm Installed". mars.nasa.gov. 28 June 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

The main arm includes five electrical motors and five joints (known as the shoulder azimuth joint, shoulder elevation joint, elbow joint, wrist joint and turret joint). Measuring 7 feet (2.1 meters) long, the arm will allow the rover to work as a human geologist would: by holding and using science tools with its turret, which is essentially its "hand".

- Boyle, Alan (4 December 2012). "NASA plans 2020 Mars rover remake". Cosmic Log. NBC News. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- "Mars 2020 Rover Tech Specs". JPL/NASA. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- "NASA Is Developing A Helicopter Drone For 2020 Mars Mission". Business 2 Community. 27 January 2015. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- Leone, Dan (19 November 2015). "Elachi Touts Helicopter Scout for Mars Sample-Caching Rover". SpaceNews. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Decision expected soon on adding helicopter to Mars 2020. Jeff Fout. Space News. 4 May 2018.

- Mars Helicopter Technology Demonstrator. (PDF) J. (Bob) Balaram, Timothy Canham, Courtney Duncan, Matt Golombek, Håvard Fjær Grip, Wayne Johnson, Justin Maki, Amelia Quon, Ryan Stern, and David Zhu. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), SciTech Forum Conference; 8–12 January 2018, Kissimmee, Florida. doi:10.2514/6.2018-0023.

- "Crazy Engineering Mars Helicopter Transcript" (PDF). JPL – NASA. 22 January 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Dreier, Casey (10 January 2013). "New Details on the 2020 Mars Rover". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- Agle, DC (1 July 2019). "A Neil Armstrong for Mars: Landing the Mars 2020 Rover". NASA. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- "Mars 2020 Rover: Entry, Descent, and Landing System". NASA. July 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- Here's an example of the crazy lengths NASA goes to land safely on Mars. Eric Berger, Ars Technica. 7 October 2019.

- "NASA Mars Rover Team Aims for Landing Closer to Prime Science Site". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- Williams, Leslie; Webster, Guy; Anderson, Gina (4 October 2016). "NASA Flight Program Tests Mars Lander Vision System". NASA. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Fresh Eyes on Mars: Mars 2020 Lander Vision System Tested through NASA's Flight Opportunities Program Oct 2016

- Ray, Justin (25 July 2016). "NASA books nuclear-certified Atlas 5 rocket for Mars 2020 rover launch". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- mars.nasa.gov. "Overview - Mars 2020 Rover". mars.nasa.gov. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "Mission: Overview". NASA. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- The Perseverance rover will visit the perfect spot to find signs of life, new studies show. Sarah Kaplan, The Washington Post. 16 November 2019.

- Hand, Eric (6 August 2015). "Mars scientists tap ancient river deltas and hot springs as promising targets for 2020 rover". Science News. Science News. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- "PIA19303: A Possible Landing Site for the 2020 Mission: Jezero Crater". NASA. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- Farley, Ken (8 September 2015). "Researcher discusses where to land Mars 2020". Phys.org. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- "2020 Landing Site for Mars Rover Mission". NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- Witze, Alexandra (11 February 2017). "Three sites where NASA might retrieve its first Mars rock". Nature. Bibcode:2017Natur.542..279W. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.21470 0 Check

|doi=value (help). Retrieved 12 February 2017. - "Send Your Name to Mars: Mars 2020". mars.nasa.gov. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Agle, D.C.; Hautaluoma, Grwy; Johnson, Alana (21 January 2020). "Nine Finalists Chosen in NASA's Mars 2020 Rover Naming Contest". NASA. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Hautaluoma, Grey; Johnsom, Alana; Agle, DC (5 March 2020). "Virginia Middle School Student Earns Honor of Naming NASA's Next Mars Rover "Perseverance"". NASA. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Chang, Kenneth (5 March 2020). "NASA's Mars 2020 Rover Gets New, Official Name: Perseverance - The robotic explorer is to join Curiosity on the red planet next year, and is expected to get more rolling companions built by China, Europe and Russia". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mars 2020. |

- Mars 2020: Official website

- Mars 2020: Assembly – Overall description (NASA)

- Mars 2020: Science Definition Team Report (NASA)

- Mars 2020: Send Your Name To Mars

- Mars 2020: Vote for the Name of the Rover

Media

- Mars 2020: Proposed Science Goals (3:09; July 2013) on YouTube

- Mars 2020: Rover and Beyond Conference (51:42; July 2014) on YouTube

- Mars 2020: Next Mission to Mars (8:57; May 2017) on YouTube

- Mars 2020: Building the Mission (3:00; December 2017) on YouTube

- Mars 2020: Building the Rover (3:50; October 2018) on YouTube

- Mars 2020: Jezero crater flyover (2:13; December 2018) on YouTube

- Mars 2020: Assembly – (Live stream; since November 2019) on YouTube

.jpg)

.jpg)

_on_1_May_from_Indonesia.jpg)