SpaceX Starship

The SpaceX Starship is a fully reusable super heavy-lift launch vehicle[3] under development by SpaceX since 2012, as a self-funded private spaceflight project.[10][11][12]

Artist's concept of Starship launch vehicle in flight | |

| Function |

|

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | SpaceX |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Cost per launch | $2 million (anticipated)[1] |

| Cost per year | 2019 |

| Size | |

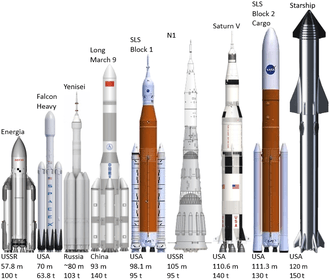

| Height | 120 m (390 ft)[2] |

| Diameter | 9 m (30 ft)[3] |

| Mass | 5,000,000 kg (11,000,000 lb) (with max payload)[4][2] |

| Stages | 2 |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO | > 100,000 kg (220,000 lb)[5] |

| Associated rockets | |

| Family | SpaceX launch vehicles |

| Comparable |

|

| Launch history | |

| Status | In development |

| Launch sites | |

| Launch date | 2020 (TBA) |

| First stage – Super Heavy | |

| Length | 70 m (230 ft)[2][5] |

| Diameter | 9 m (30 ft)[5] |

| Empty mass | 180,000 kg (400,000 lb) (estimated)[4] |

| Gross mass | 3,580,000 kg (7,890,000 lb) [4][5][6] |

| Propellant mass | 3,400,000 kg (7,500,000 lb)[5] |

| Engines | 31 Raptor[7] |

| Thrust | 72,000 kN (16,000,000 lbf)[5] |

| Specific impulse | 330 s (3.2 km/s)[8] |

| Fuel | Subcooled CH 4 / LOX[3] |

| Second stage – Starship | |

| Length | 50 m (160 ft)[5] |

| Diameter | 9 m (30 ft)[5] |

| Empty mass | 120,000 kg (260,000 lb)[4] |

| Gross mass | 1,320,000 kg (2,910,000 lb)[4][5][6] |

| Propellant mass | 1,200,000 kg (2,600,000 lb)[5] |

| Engines | 6 Raptor[3] |

| Thrust | c. 12,000 kN (2,700,000 lbf)[3] |

| Specific impulse | 380 s (3.7 km/s) (vacuum)[9] |

| Fuel | Subcooled CH 4 / LOX[3] |

The second stage of Starship—which is also commonly referred to as "Starship"[13]:16:20–16:48—is designed as a long-duration cargo and passenger-carrying spacecraft in its own right, and is expected to be initially used without any booster stage at all, as part of an extensive development program to get launch and landing working and iterate on a variety of design details, particularly with respect to atmospheric reentry of the vehicle.[12][14][15][16]

While the spacecraft will be tested on its own initially at suborbital altitudes, it will be used on orbital launches with an additional booster stage, the Super Heavy, where the spacecraft will serve as the second stage on a two-stage-to-orbit launch vehicle.[17]

Integrated system testing of a proof of concept for Starship began in March 2019, with the addition of a single Raptor rocket engine to a reduced-height prototype, nicknamed Starhopper—similar to Grasshopper, a equivalent prototype of the Falcon 9 reusable booster. Starhopper was used from April through August 2019 for static testing and low-altitude, low-velocity flight testing of vertical launches and landings[18] in July and August. More prototype Starships are under construction[19] and are expected to go through several iterations. All test articles have a 9-meter diameter (30 ft) stainless steel hull.

SpaceX is planning to launch commercial payloads using Starship no earlier than 2021.[20] In April 2020, NASA selected a modified human rated Starship system as one of three lunar landing systems to receive funding for a 10-month long initial design phase for the Artemis program.[21]

Nomenclature

As of 2020, the combination of Starship spacecraft and Super Heavy booster is called the "Starship system" by SpaceX in their payload users guide[22] or sometimes, as on the SpaceX website, the term "Starship" is used as a collective term for both the Starship spacecraft and the Super Heavy booster.[3] However, the name of Starship has changed many times.[23]

At least as early as 2005, SpaceX used the codename, "BFR", for a conceptual heavy-lift vehicle, "far larger than the Falcon family of vehicles,"[24][25] with a goal of 100 t (220,000 lb) to orbit. Beginning in mid-2013, SpaceX referred to both the mission architecture and the vehicle as the Mars Colonial Transporter.[26] By the time a large 12-meter diameter design concept was unveiled in September 2016, SpaceX had begun referring to the overall system as the Interplanetary Transport System.

With the announcement of a new 9-meter design in September 2017, SpaceX resumed referring to the vehicle as "BFR".[27][28][29] Musk said in the announcement, "we are searching for the right name, but the code name, at least, is BFR."[8] SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell subsequently stated that BFR stands for, "Big Falcon Rocket".[30] However, Elon Musk had explained in the past that although BFR is the official name, he drew inspiration from the BFG weapon in the Doom video games.[31] The BFR had also occasionally been referred to informally by the media and internally at SpaceX as "Big Fucking Rocket".[32][33][34] At the time, the second stage/spacecraft was referred to as "BFS".[lower-alpha 1][35][36][37] The booster first stage was also at times referred to as the "BFB".[lower-alpha 2][38][39][40] In November 2018, the spaceship was renamed Starship, and the first stage booster was named Super Heavy.[17][11]

Notably, in the fashion of SpaceX, even that term "Super Heavy" had been previously used by SpaceX in a different context. In February 2018, at about the time of the first Falcon Heavy launch, Musk had "suggested the possibility of a Falcon Super Heavy—a Falcon Heavy with extra boosters. 'We could really dial it up to as much performance as anyone could ever want. If we wanted to we could actually add two more side boosters and make it Falcon Super Heavy.'"[41]

History

The launch vehicle was initially mentioned in public discussions by SpaceX CEO Elon Musk in 2012 as part of a description of the company's overall Mars system architecture, then known as "Mars Colonial Transporter" (MCT).[42] By August 2014, media sources speculated that the initial flight test of the Raptor-driven super-heavy launch vehicle could occur as early as 2020, in order to fully test the engines under orbital spaceflight conditions; however, any colonization effort was then reported to continue to be "deep into the future".[43]

In mid-September 2016, Musk noted that the Mars Colonial Transporter name would not continue, as the system would be able to "go well beyond Mars", and that a new name would be needed. The name selected was "Interplanetary Transport System" (ITS), although in an AMA on Reddit on October 23, 2016, Musk stated, "I think we need a new name. ITS just isn't working. I'm using BFR and BFS for the rocket and spaceship, which is fine internally, but...", without stating what the new name might be.[44] In September 2017, at the 68th annual meeting of the International Astronautical Congress, SpaceX unveiled an updated vehicle design. Musk said, "we are searching for the right name, but the code name, at least, is BFR."[8]

In a September 2018 announcement of a planned 2023 lunar circumnavigation mission, a private spaceflight called #dearMoon project,[45] Musk showed another redesigned concept for the second stage and spaceship with three rear fins and two front canard fins added for atmospheric entry, replacing the previous delta wing and split flaps shown a year earlier. The design was to use seven identically-sized Raptor engines in the second stage; the same engine model as would be used on the first stage. The second stage design had two small actuating canard fins near the nose of the ship, and three large fins at the base, two of which would actuate, with all three serving as landing legs.[46] Additionally, SpaceX also stated in the second half of the month that they were "no longer planning to upgrade Falcon 9 second stage for reusability."[47] The two major parts of the launch vehicle were given descriptive names in November: "Starship" for the upper stage and "Super Heavy" for the booster stage, which Musk pointed out was "needed to escape Earth’s deep gravity well (not needed for other planets or moons)."[17]

In January 2019, Elon Musk announced that the Starship would no longer be constructed out of carbon fiber, and that stainless steel would be used instead to build the Starship. Musk cited several reasons including cost, strength, and ease of production to justify making the switch.[48]

In May 2019, the Starship design changed back to just six Raptor engines, with three optimized for sea-level and three optimized for vacuum.[49] By late May 2019, the first prototype, Starhopper, was preparing for untethered flight tests in South Texas, while two orbital prototypes were under construction, one in South Texas begun in March and one on the Florida space coast begun before May. The build of the first Super Heavy booster stage was projected to be able to start by September.[18] At the time, neither of the two orbital prototypes yet had aerodynamic control surfaces nor landing legs added to the under construction tank structures, and Musk indicated that the design for both would be changing once again.[50] On 21 September 2019, the externally-visible "moving fins"[51] began to be added to the Mk1 prototype, giving a view into the promised mid-2019 redesign of the aerodynamic control surfaces for the test vehicles.[52][53]

In June 2019, SpaceX publicly announced discussions had begun with three telecommunications companies for using Starship, rather than Falcon 9, for launching commercial satellites for paying customers in 2021. No specific companies or launch contracts were announced at that time.[20]

In July 2019, the Starhopper made its initial flight test, a "hop" of around 20 m (66 ft) altitude,[54] and a second and final "hop" in August, reaching an altitude of around 150 m (490 ft)[55] and landing around 100 m (330 ft) from the launchpad.

SpaceX completed most of the Boca Chica prototype, the Starship Mk1, in time for Musk's next public update in September 2019. Watching the construction in progress before the event, observers online circulated photos and speculated about the most visible change, a move to two tail fins from the earlier three. During the event, Musk added that landing would now be accomplished on six dedicated landing legs, following a re-entry protected by glass heat tiles.[56] Updated specifications were provided: when optimized, Starship was expected to mass at 120,000 kg (260,000 lb) empty and be able to initially transport a payload of 100,000 kg (220,000 lb) with an objective of growing that to 150,000 kg (330,000 lb) over time. Musk suggested that an orbital flight might be achieved by the fourth or fifth test prototype in 2020, using a Super Heavy booster in a two-stage-to-orbit launch vehicle configuration,[57][58] and emphasis was placed on possible future lunar missions.[59]

In September 2019, Elon Musk unveiled Starship Mk1.[60][61] At the time, construction of Mk3 was expected to start in about a month.[61]

In 2019, the cost per launch for Starship was estimated by SpaceX to be as low as US$2 million once the company achieves a robust operational cadence and achieves the technological advance of full and rapid reusability. Full reusability of the second stage of Starship is a fundamental design goal for the entire Starship development program, but success is uncertain.[1] Elon Musk has said in 2020 that, with a high flight rate, they could potentially go even lower, with a fully-burdened marginal cost on the order of US$10 per kilogram of payload launched to low-Earth orbit.[62]

In November 2019, the Mk1 test article in Texas came apart in a tank pressure test, and SpaceX stated they would cease to build the Mk2 prototype under construction in Florida and move on to work on the Mk3 article. A few weeks later, the work on the vehicles in Florida slowed down substantially, with some assemblies that had been built in Florida for those vehicles being transported to the Texas Starship assembly location, and a reported 80 percent reduction in the workforce at the Florida assembly location as SpaceX pauses activities there. Apparently, at the same time the Mk4 vehicle under construction in Florida was cancelled.[63]

The Mk3 article was renamed Starship SN1 by SpaceX, to signify the major evolution in building techniques: the rings were now taller and each was made of one single sheet of steel, drastically reducing the welding lines (thus failure points). Also the worksite was expanded with more tents, structures and upgraded machinery to give the workers a much better controlled environment, allowing for better precision work and, more importantly, better quality welds. Smaller articles were made and tested to destruction to validate the new bulkheads design.[64] This was a significant change of pace for SpaceX's approach.

In February 2020, SN1 too was destroyed when undergoing pressurization.[65] The company then focused on resolving the problem that led to SN1's failure by assembling a stripped down version of their next planned prototype, SN2.[66][67] This time the test was successful and SpaceX began work on SN3.[68][67] However, in April 2020 SN3 was also destroyed during testing due to a test configuration error.[67][69] At that time, construction of SN4 was underway.[69]

On April 26, 2020, Starship SN4 became the first full-scale prototype to pass a cryogenic proof test, in which the ship’s liquid oxygen and methane was replaced with similarly frigid but non-explosive liquid nitrogen. SN4 was only pressurized to 4.9 bar (~70 psi), which is more than enough to perform a small flight test. On May 5, 2020, SN4 completed a Raptor static fire with one mounted Raptor engine and became the first full Starship tank to pass a Raptor static fire.[70] SN4 would complete a total of 4 short static fires (2 to 5 seconds long) before being destroyed in a massive explosion occurring at the end of a test fire on May 29.[71]

While the Starship program had a small development team for several years, and a larger development and build team since late 2018, Musk declared in June 2020 that Starship is the top SpaceX priority, except for anything related to reduction of Crew Dragon return risk for the NASA Demo-2 flight to the ISS.[72]

Description

Super Heavy

Super Heavy,[11] the booster stage "needed to escape Earth’s deep gravity well",[16] is expected to be 70 metres (230 ft) long and 9 metres (30 ft) in diameter with a gross liftoff mass of 3,680,000 kg (8,110,000 lb).[4][6] It is to be constructed of stainless steel tanks and structure, holding subcooled liquid methane and liquid oxygen (CH

4/LOX) propellants, powered by 24 to 37 Raptor rocket engines[73] that will provide 72,000 kilonewtons (16×106 lbf) total liftoff thrust.[73][3]

The specification propellant capacity of Super Heavy was shown as 3,400,000 kg (7,500,000 lb) in May 2020,[5] three percent more than estimated in September 2019.[3]

The initial prototype Super Heavy will be full size.[74] It is expected however, to initially fly with less than the full complement of 31[7] engines, perhaps approximately 20.[75]

In September 2019, several Super Heavy external design changes were announced. The booster stage is now intended to have six fins that serve exclusively[56]:26:25–28:35 as fairings to cover the six landing legs, and four diamond-shaped welded steel grid fins[76] to provide aerodynamic control on descent.[77]

Landing

In September 2016, Elon Musk described the possibility of landing the ITS booster on the launch pad.[78] He redescribed this in September 2017 with the Big Falcon Booster (BFB).[79][80][81][36] According to the SpaceX animation of the launch of Starship, the Super Heavy booster is not expected to land on the launch pad at all.[82] In 2019, Musk announced that it will initially have landing legs to support the early VTVL development testing of Super Heavy.[83][84][85]

Starship upper stage

As of September 2019, the Starship upper stage is expected to be a 9-metre-diameter (30 ft), 50-metre-tall (160 ft), fully reusable spacecraft with a dry mass of 120 t (260,000 lb) or less,[56] powered by six methane/oxygen-propellant Raptor engines.[49] Total Starship thrust will be approximately 2,600,000 lbf (11,500 kN).[86]

Unusual for previous launch vehicle and spacecraft designs, Starship is intended to function both as a second stage to reach orbital velocity on launches from Earth, and also be used in outer space as an on-orbit long-duration spacecraft. Starship is being designed so as to be capable of reentering Earth's atmosphere from orbital velocities and landing vertically, with a design goal of rapid reusability.[56]

Starship will use three sea-level optimized Raptor engines and three vacuum-optimized Raptor engines. These sea-level engines are identical to the engines on the Super Heavy booster. Transport use in space is expected to utilize a vacuum-optimized Raptor engine variant to optimize specific impulse (Isp) to approximately 380 s (8,300 mph; 3.7 km/s).[56]

Starship is planned to eventually be built in at least these operational variants:[80][87]

- Spaceship: a large, long-duration spacecraft capable of carrying passengers or cargo to interplanetary destinations, to LEO, or Earth-to-Earth spaceflight.[80]

- Satellite delivery spacecraft: a vehicle able to transport and place spacecraft into orbit,[20] or handle the in-space recovery of spacecraft and space debris for return to Earth or movement to another orbit. In the March 2020 users guide, this was shown with a large cargo bay door that can open in space to facilitate delivery and pickup of cargo.[80]

- Tanker: a cargo-only propellant tanker to support the refilling of propellants in Earth orbit. The tanker will enable launching a heavy spacecraft to interplanetary space as the spacecraft being refueled can use its tanks twice, first to reach LEO and afterwards to leave Earth orbit. The tanker variant, also required for high-payload lunar flights, is expected to come only later; initial in-space propellant transfer will be from one standard Starship to another.[88]

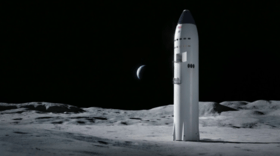

- Lunar-surface-to-orbit transport: A variant of Starship without airbrakes or heat shielding that is required for in-atmosphere-operations. Additionally the ship will be equipped a docking port on the nose and have white paint (as opposed to the bare steel planned for regular Starships). On 30 April 2020, NASA selected SpaceX to develop a human-rated lunar lander for the Artemis program, therefore requiring SpaceX to develop an approach for a direct lunar landing.

Characteristics of Starship are to include:[80][36][79][81]

- ability to re-enter Earth's atmosphere and retropropulsively land on a designated landing pad, landing reliability is projected by SpaceX to ultimately be able to achieve "airline levels" of safety due to engine-out capability

- rapid reusability without the need for extensive refurbishment

- automated rendezvous and docking operations

- on-orbit propellant transfers between Starships[88]

- ability to reach the Moon and Mars after on-orbit propellant loading

- stainless steel structure and tank construction. Its strength-to-mass ratio should be comparable to or better than the earlier SpaceX design alternative of carbon fiber composites across the anticipated temperature ranges, from the low temperatures of cryogenic propellants to the high temperatures of atmospheric reentry[89]

- some parts of the craft will be built with a stainless steel alloy that "has undergone [a type of] cryogenic treatment, in which metals are ... cold-formed/worked [to produce a] cryo-treated steel ... dramatically lighter and more wear-resistant than traditional hot-rolled steel."[89]

- methox (methane gas/oxygen gas)[90] pressure fed hot gas reaction control system (RCS) thrusters for attitude control, including the final pre-landing pitch-up maneuver from belly flop to tail down, and stability during high-wind landings up to 60 km/h (37 mph).[91] Initial prototypes are using nitrogen cold gas thrusters, which have a substantially less-efficient mass efficiency, but are expedient for quick building to support early prototype flight testing.[56]

- a thermal protection system against the harsh conditions of atmospheric reentry. This will include ceramic tiles,[92][93] after earlier evaluating[92] a double stainless-steel skin with active coolant flowing in between the two layers or with some areas additionally containing multiple small pores that will allow for transpiration cooling.[94][95][96]) Options under study included hexagonal ceramic[97] tiles that could be used on the windward side of Starship.

- a novel atmospheric re-entry approach for planets with atmospheres. While retropropulsion is intended to be used for the final landing maneuver on the Earth, Moon, or Mars, 99.9% of the energy dissipation on Earth reentry is to be removed aerodynamically, and on Mars, 99% aerodynamically even using the much thinner Martian atmosphere.[98]

- as envisioned in the 2017 design unveiling, the Starship is to have a pressurized volume of approximately 1,000 m3 (35,000 cu ft), which could be configured for up to 40 cabins, large common areas, central storage, a galley, and a solar flare shelter for Mars missions.[36]

- flexible design options; for example, a possible design modification to the base Starship—expendable 3-engine Starship with no fairing, rear fins, nor landing legs in order to optimize its mass ratio for interplanetary exploration with robotic probes.[99]

According to Musk, when Starship is used for BEO launches to Mars, the functioning of the overall expedition system will necessarily include propellant production on the Mars surface. He says that this is necessary for the return trip and to reuse the spaceship to keep costs as low as possible. He also says that lunar destinations (circumlunar flybys, orbits and landings) will be possible without lunar-propellant depots, so long as the spaceship is refueled in a high-elliptical orbit before the lunar transit begins.[80] Some lunar flybys will be possible without orbital refueling as evidenced by the mission profile of the #dearMoon project.[9]

The SpaceX approach is to tackle the hardest problems first, and Musk sees the hardest problem for getting to sustainable human civilization on Mars to be building a fully-reusable orbital Starship, so that is the major focus of SpaceX resources as of 2020.[10] For example, it is planned for the spacecraft to eventually incorporate life support systems, but as of September 2019, Musk stated that it is yet to be developed, as the first flights will be uncrewed.[100][101][102]

Starship Human Landing System

A modified version known as the Starship Human Landing System (Starship HLS) was selected by NASA for potential use for long-duration crewed lunar landings as part of NASA's Artemis program. The Starship HLS variant is being designed to stay on and around the Moon and as such both the heat shield and air-brakes—integral parts of the main Starship design—are not included in the Starship HLS design. The variant will use high-thrust methox RCS thrusters located mid-body on Starship HLS during the final "tens of meters" of the terminal lunar descent and landing,[103][104], and will also include a smaller crew area and a much larger cargo bay, be powered by a solar array located on its nose below the docking port. SpaceX intends to use the same high-thrust RCS thrusters for liftoff from the lunar surface.[103]:50:30 If built, the HLS variant would be launched to lunar orbit via the Super Heavy booster and would use orbital refueling to reload propellants into Starship HLS for the lunar transit and lunar landing operations. In the mission concept, a NASA Orion spacecraft would carry a NASA crew to the lander where they would depart and descend to the surface in Starship HLS. After Lunar surface operations, it would ascend using the same Starship HLS vehicle and return the crew to the Orion. Although not confirmed yet, the vehicle in theory could be refueled in orbit to carry more crews and cargo to the surface.[105][106]

SpaceX is one of three organizations who are developing their lunar lander designs for the Artemis program over a 10-month period in 2020–21. If SpaceX completes the milestone-based requirements of the design contract, then NASA will pay SpaceX US$135 million in design development funding. The other teams selected are the 'National Team'—led by Blue Origin but including Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Draper—with US$579 million in design funding and Dynetics—with SNC and other unspecified companies—with US$253 million in NASA funding.[106][105] At the end of the ten month program, NASA will evaluate which contractors will be offered contracts for initial demonstration missions and select firms for development and maturation of lunar lander systems.[106][107]

Prototypes

Two (Starhopper, Mk1) test articles were being built by March 2019, and three (Starhopper, Mk1, Mk2) by May.[108] The low-altitude, low-velocity Starhopper was used for initial integrated testing of the Raptor rocket engine with a flight-capable propellant structure, and was slated to also test the newly designed autogenous pressurization system that is replacing traditional helium tank pressurization as well as initial launch and landing algorithms for the much larger 9-metre-diameter (30 ft) rocket.[94] SpaceX originally developed their reusable booster technology for the 3-meter-diameter Falcon 9 from 2012 to 2018. The Starhopper prototype was also the platform for the first flight tests of the full-flow staged combustion methalox Raptor engine, where the hopper vehicle was flight tested with a single engine in July/August 2019,[109] but could be fitted with up to three engines to facilitate engine-out tolerance testing.[94]

The high-altitude, high-velocity 'Starship orbital prototypes' (everything after Starhopper) are planned to be used to develop and flight test thermal protection systems and hypersonic reentry control surfaces.[94] Each orbital prototype is expected to be outfitted with more than three Raptor engines.[18][110]

Starhopper

The construction of the initial test article—the Starship Hopper[111] or Starhopper[112][113]—was begun in early December 2018 and the external frame and skin was complete by 10 January 2019. Constructed outside in the open on a SpaceX property just two miles (3.2 km) from Boca Chica Beach in South Texas, the external body of the rocket rapidly came together in less than six weeks from half inch (12.5mm) steel.[114] Originally thought by onlookers at the SpaceX South Texas Launch Site to be the initial construction of a large water tower, the stainless steel vehicle was built by welders and construction workers in more of a shipyard form of construction than traditional aerospace manufacturing. The full Starhopper vehicle is 9 metres (30 ft) in diameter and was originally 39 metres (128 ft) tall in January 2019.[89][115] Subsequent wind damage to the nose cone of the vehicle resulted in a SpaceX decision to scrap the nose section, and fly the low-velocity hopper tests with no nose cone, resulting in a much shorter test vehicle.[116]

From mid-January to early-March, a major focus of the manufacture of the test article was to complete the pressure vessel construction for the liquid methane and liquid oxygen tanks, including plumbing up the system, and moving the lower tank section of the vehicle two miles (3.2 km) to the launch pad on 8 March.[117] Integrated system testing of the Starhopper—with the newly-built ground support equipment (GSE) at the SpaceX South Texas facilities—began in March 2019. "These tests involved fueling Starhopper with LOX and liquid methane and testing the pressurization systems, observed via icing of propellant lines leading to the vehicle and the venting of cryogenic boil off at the launch/test site. During a period of over a week, StarHopper underwent almost daily tanking tests, wet dress rehearsals and a few pre-burner tests."[94]

Following initial integrated system testing of the Starhopper test vehicle with Raptor engine serial number 2 (Raptor SN2) in early April, the engine was removed for post-test analysis and several additions were made to the Starhopper. Attitude control system thrusters were added to the vehicle, along with shock absorbers for the non-retractable landing legs, and quick-disconnect connections for umbilicals. Raptor SN4 was installed in early June for fit checks, but the first test flight that is not tethered was expected to fly with Raptor SN5,[116] until it suffered damage during testing at SpaceX Rocket Development and Test Facility, in McGregor, Texas. Subsequently, Raptor S/N 6 was the engine used by Starhopper for its untethered flights.[118]

High-altitude prototypes

By December 2018, initial construction of two high-altitude prototype ships had begun, referred to as Mk1 at Boca Chica, Texas,[119] and Mk2 at the space coast of Florida in Cocoa.[18][119] Planned for high-altitude and high-velocity testing,[120] the prototypes were described to be taller than the Starhopper, have thicker skins, and a smoothly curving nose section.[18][18][110][121] Both prototypes measured 9 m (30 ft) in diameter by approximately 50 m (160 ft) in height.[122]

On 20 November 2019, the Starship Mk1 was partially destroyed during max pressure tank testing, when the forward LOX tank ruptured along a weld line of the craft's steel structure, propelling the bulkhead several meters upwards. The upper bulkhead went airborne and landed some distance away from the craft. No injuries were reported.[123] In a statement concerning the test anomaly, SpaceX said they will retire the Mk1 and Mk2 prototypes after the incident, and focus on Mk3 and Mk4 designs, which are closer to the flight specifications.[124][125]

Construction had begun on the Mk2 Starship in Florida by mid-October 2019,[126] but work then ceased in Florida (with apparent cancellation of Mk2[127]) and focused on the Texas site.[128] The prototype in Texas (Mk3) was renamed to SN1. It was destroyed during a pressure test on 28 February 2020.[129] After this incident, SpaceX announced they would focus on the next prototype, the Starship SN2.[65] SN2 successfully went through a pressure and cryo test, but was not used for a static fire or hop. Instead, SpaceX moved on to SN3, the next prototype. SN3's cryo test then failed, the result being the LOX (Liquid Oxygen) Tank collapsing due to underpressurisation.[130] On 26 April 2020, SN4 successfully completed a cryogenic pressure test.[131] On 29 May 2020, SN4 exploded after engine testing.

Testing

The Starhopper was used to flight test a number of subsystems of the Starship and to begin to expand the flight envelope as the Starship design is iterated.[115][132][133] Initial tests began in March 2019.[134] All test flights of the Starhopper were at low altitude.[135] On 3 April 2019, SpaceX conducted a successful static fire test in Texas of its Starhopper vehicle, which ignited the engine while the vehicle remained tethered to the ground.[136]

The first static fire test of the Starhopper, with a single Raptor engine attached, occurred on 3 April 2019. The firing was a few seconds in duration, and was classed as successful by SpaceX.[94] A second tethered test followed just two days later, on 5 April.[108][137]

By May 2019, SpaceX was planning to conduct flight tests both in South Texas and on the Florida space coast.[14][18][116] The FAA issued a one-year experimental permit in June 2019 to fly Starhopper at Boca Chica, including pre-flight and post-flight ground operations.[138]

On 16 July 2019, the Starhopper caught fire. The damage to Starhopper was unknown at the time.[139]

The maiden flight test of the Starhopper test vehicle, and also the maiden flight test of any full-flow staged combustion rocket engine ever, was on 25 July 2019, and attained a height of 18 m (59 ft).[109][140] This was not a full-duration burn but a 22-second test, and it accidentally set fire to nearby vegetation.[141] SpaceX is developing their next-generation rocket to be reusable from the beginning, just like an aircraft, and thus needs to start with narrow flight test objectives, while still aiming to land the rocket successfully to be used subsequently in further tests to expand the flight envelope.[109] The second and final untethered test flight of the Starhopper test article was carried out on 27 August 2019, to a VTVL altitude of 150 m (490 ft).[118]

| Flight No. | Date and time (UTC) | Vehicle | Launch site | Suborbital apogee | Outcome | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 April 2019 | Starhopper | Boca Chica, Texas | ~ 1 m (3 ft) | Success | — |

| Tethered hop which hit tethered limits. With a single Raptor SN2 engine.[116] | ||||||

| 2 | 25 July 2019[142] | Starhopper | Boca Chica, Texas | 20 m (66 ft)[109] | Success | ~ 22 seconds |

| First free flight test. Single Raptor engine, S/N 6. Was previously scheduled for the day before but was aborted.[109] A test flight attempt on 24 July was scrubbed.[143] | ||||||

| 3 | 27 August 2019[118] 22:00[144] |

Starhopper | Boca Chica, Texas | 150 m (490 ft)[118] | Success | ~ 57 seconds[145] |

| Single Raptor SN6 engine. SpaceX called this the "150 meter Starhopper Test" on their livestream. Starhopper was retired after this launch, with some parts being reused for other tests.[118][146] The test flight attempt on 26 August was scrubbed due to a problem with the Raptor engine igniters.[143] | ||||||

| 4 | TBD[147] | SN5[147] | Boca Chica, Texas | 150 m (490 ft)[147] | Planned | |

Intended uses

Starship is intended to become the primary SpaceX orbital vehicle, as SpaceX has announced it intends to eventually replace its existing Falcon 9 launch vehicle and Dragon 2 fleet with Starship, which is expected to take cargo to orbit at far lower cost than any other existing launch vehicle, whether from SpaceX or other launch service provider.[15][80][8]:24:50–27:05 In November 2019 Elon Musk estimated that fuel will cost $900,000 per launch and total launch costs could drop as low as $2 million.[148]

Starship is an architecture designed to do many diverse spaceflight missions, principally due to the very low marginal cost per mission that the fully-reusable spaceflight vehicles bring to spaceflight technology that were absent in the first six decades after humans put technology into space.[13]:30:10–31:30 Specifically, Starship is designed to be utilized for:[15][79]

- Earth-orbit satellite delivery market. In addition to the standard external launch market that SpaceX has been servicing since 2013, the company intends to use Starship to launch the largest portion of its own internet satellite constellation, Starlink, with more than 12,000 satellites intended to be launched by 2026, more than six times the total number of active satellites on orbit in 2018.[149]

- long-duration spaceflights in the cislunar region

- Mars transportation, both as cargo ships as well as passenger-carrying transport

- long-duration flights to the outer planets, for cargo and astronauts[150]

- Reusable lunar lander, for use transporting astronauts and cargo to and from the moon's surface and Lunar Gateway in lunar orbit via Starship HLS;[105] as well as more advanced heavy cargo lunar use cases that are envisioned by SpaceX but are not any part of the HLS variant that NASA has contracted with SpaceX for early design work.[13]:13:34–20:10

In 2017, SpaceX mentioned the theoretical ability of using a boosted Starship to carry passengers on suborbital flights between two points on Earth in under one hour, providing commercial long-haul transport on Earth, competing with long-range aircraft.[151][152] SpaceX however announced no concrete plans to pursue the two stage "Earth-to-Earth" use case.[8][132][153] Over two years later, in May 2019, Musk floated the idea of using single-stage Starship to travel up to 10,000 kilometers (6,200 mi) on Earth-to-Earth flights at speeds approaching Mach 20 (25,000 km/h; 15,000 mph) with an acceptable payload saying it "dramatically improves cost, complexity & ease of operations."[154] In June 2020, Musk estimated that Earth-to-Earth test flights could begin in "2 or 3 years", i.e. 2022 or 2023, and that planning was underway for "floating superheavy-class spaceports for Mars, Moon & hypersonic travel around Earth."[155]

Funding

SpaceX has been developing the Starship with private funding, including the Raptor rocket engine used on both stages of the vehicle, since 2012.[12] In 2020, SpaceX have contracted with NASA to do limited early design work for 10 months on a human lunar lander variant Starship—Starship HLS—that may potentially be used to land astronauts on the lunar surface as part of the NASA Artemis program after 2024.

The development work on the new two-stage launch vehicle design is privately funded by SpaceX. The entire project is possible only as a result of SpaceX's multi-faceted approach focusing on the reduction of launch costs.[156]

The full build-out of the Mars colonization plans was envisioned by Musk in 2016 to be funded by both private and public funds. The speed of commercially available Mars transport for both cargo and humans will be driven, in large part, by market demand as well as constrained by the technology development and development funding.

Elon Musk said that there is no expectation of receiving NASA contracts for any of the ITS system work SpaceX was doing. He also indicated that such contracts, if received, would be good.[157]

In 2017 the company settled on a 9 meter diameter design and commenced procuring equipment for vehicle manufacturing operations. In late 2018, they switched the design from carbon composite materials for the main structures to stainless steel, further lowering build costs.[45] By late 2019, SpaceX projected that, with company private investment funding, including contractual funds from Yusaku Maezawa who had recently contracted for a private lunar mission in 2023, they have sufficient funds to advance the Earth-orbit and lunar-orbit extent of flight operations, although they may raise additional funds in order "to go to the Moon or landing on Mars."[12]

In April 2020, NASA announced they would pay SpaceX US$135 million for design and initial development over a 10-month design period for a variation of the Starship second-stage vehicle and spaceship—a "Starship Human Landing System," or Starship HLS—as a Lunar human landing system for the NASA Artemis Program; NASA is paying US$579 million and US$253 million to other contractors developing similar lunar landing designs.[106][107]

Criticism

The Starship launch vehicle has been mostly criticized for not addressing the protection from ionizing radiation in more detail;[158][159][160][161][162][163][164][165] Musk has stated that he thinks the transit time will be too insignificant to lead to an increased risk of cancer, and that "it's not too big of a deal".[158][166][167]

See also

- List of Starship flights

- List of crewed spacecraft

- Mars to Stay – Mars colonization architecture proposing no return vehicles

- Space colonization – Concept of permanent human habitation outside of Earth

- Space exploration – Discovery and exploration of outer space

Notes

- Big Falcon Ship or Big Fucking Ship

- Big Falcon Booster or Big Fucking Booster

References

- Wall, Mike (19 November 2019). "SpaceX's Starship May Fly for Just $2 Million Per Mission, Elon Musk Says". Space.com. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- @elonmusk (16 March 2020). "Slight booster length increase to 70m, so 117m for whole system. Liftoff mass ~5000 mT" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Starship". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- @elonmusk (26 September 2019). "Mk1 ship is around 200 tons dry & 1400 tons wet, but aiming for 120 by Mk4 or Mk5. Total stack mass with max payload is 5000 tons" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Starship : service to Earth orbit, Moon, Mars, and beyond". SpaceX. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Lawler, Richard. "SpaceX's plan for in-orbit Starship refueling: a second Starship". Engadget. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Elon Musk: Super Heavy will have 31 engines, not 37". Twitter. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Elon Musk (29 September 2017). Becoming a Multiplanet Species (video). 68th annual meeting of the International Astronautical Congress in Adelaide, Australia: SpaceX. Retrieved 14 December 2017 – via YouTube.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Musk, Elon (17 September 2018). First Private Passenger on Lunar BFR Mission. SpaceX. Retrieved 18 September 2018 – via YouTube.

- berger, Eric (5 March 2020). "Inside Elon Musk's plan to build one Starship a week—and settle Mars". Ars Technica. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

Musk tackles the hardest engineering problems first. For Mars, there will be so many logistical things to make it all work, from power on the surface to scratching out a living to adapting to its extreme climate. But Musk believes that the initial, hardest step is building a reusable, orbital Starship to get people and tons of stuff to Mars. So he is focused on that.

- Lawler, Richard (20 November 2018). "SpaceX BFR has a new name: Starship". Engadget. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Berger, Eric (29 September 2019). "Elon Musk, Man of Steel, reveals his stainless Starship". Ars Technica. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Cummings, Nick (11 June 2020). Human Landing System: Putting Boots Back on the Moon. American Astronautical Society. Retrieved 12 June 2020 – via YouTube.

- Berger, Eric (15 May 2019). "SpaceX plans to A/B test its Starship rocketship builds". Ars Technica. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Chris Gebhardt (29 September 2017). "The Moon, Mars, & around the Earth – Musk updates BFR architecture, plans". Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (19 November 2018). "Starship is the spaceship/upper stage & Super Heavy is the rocket booster needed to escape Earth's deep gravity well (not needed for other planets or moons)" (Tweet). Retrieved 10 August 2019 – via Twitter.

- Boyle, Alan (19 November 2018). "Goodbye, BFR … hello, Starship: Elon Musk gives a classic name to his Mars spaceship". GeekWire. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

Starship is the spaceship/upper stage & Super Heavy is the rocket booster needed to escape Earth’s deep gravity well (not needed for other planets or moons)

- Gray, Tyler (28 May 2019). "SpaceX ramps up operations in South Texas as Hopper tests loom". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Musk, Elon (8 February 2020). "First two domes in frame are for SN2, third is SN1 thrust dome". @elonmusk. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- Henry, Caleb (28 June 2019). "SpaceX targets 2021 commercial Starship launch". SpaceNews. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- "SpaceX, Blue Origin and Dynetics will build human lunar landers for NASA's next trip back to the Moon". TechCrunch. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Starship Users Guide, Revision 1.0, March 2020" (PDF). SpaceX/files. SpaceX. March 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

SpaceX’s Starship system represents a fully reusable transportation system designed to service Earth orbit needs as well as missions to the Moon and Mars. This two-stage vehicle—composed of the Super Heavy rocket (booster) and Starship (spacecraft)

- Baylor, Michael (21 September 2019). "Elon Musk's upcoming Starship presentation to mark 12 months of rapid progress". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

While the names of the vehicles have changed numerous times over the years, the spacecraft is currently called Starship with its first stage booster called Super Heavy.

- Jeff Foust (14 November 2005). "Big plans for SpaceX". The Space Review. Archived from the original on 24 November 2005. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- SPACEX set maiden flight – goals Archived 31 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine, NASASpaceFlight.com, 18 November 2005, accessed 31 January 2019.

- Steve Schaefer (6 June 2013). "SpaceX IPO Cleared For Launch? Elon Musk Says Hold Your Horses". Forbes. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Foust, Jeff (29 September 2017). "Musk unveils revised version of giant interplanetary launch system". SpaceNews. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- William Harwood (29 September 2017). "Elon Musk revises Mars plan, hopes for boots on ground in 2024". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

The new rocket is still known as the BFR, a euphemism for 'Big (fill-in-the-blank) Rocket.' The reusable BFR will use 31 Raptor engines burning densified, or super-cooled, liquid methane and liquid oxygen to lift 150 tons, or 300,000 pounds, to low Earth orbit, roughly equivalent to NASA’s Saturn 5 moon rocket.

- "Artist's Rendering Of The BFR". SpaceX. 12 April 2017. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Mike Wall. "What's in a Name? SpaceX's 'BFR' Mars Rocket Acronym Explained". space.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- Heath, Chris (12 December 2015). "Elon Musk Is Ready to Conquer Mars". GQ. Archived from the original on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- Fernholz, Tim (20 March 2018). Rocket Billionaires: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the New Space Race. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 244. ISBN 978-1328662231. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

SpaceX would build a huge rocket: the BFR, or Big Falcon Rocket—or, more crudely among staff, the Big Fucking Rocket

- Slezak, Michael; Solon, Olivia (29 September 2017). "Elon Musk: SpaceX can colonise Mars and build moon base". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- Burgess, Matt (29 September 2017). "Elon Musk's Big Fucking Rocket to Mars is his most ambitious yet". Wired UK. London: Condé Nast Publications. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- Space tourists will have to wait as SpaceX plans bigger rocket Archived 19 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Stu Clark, The Guardian. 8 February 2018.

- "Making Life Multiplanetary: Abridged transcript of Elon Musk's presentation to the 68th International Astronautical Congress in Adelaide, Australia" (PDF). SpaceX. September 2017.

- SpaceX signs its first passenger to fly aboard the Big Falcon Rocket Moon mission Archived 15 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine. CatchNews. 14 September 2018.

- Dave Mosher (24 December 2018). "Elon Musk: SpaceX to launch a Starship spaceship prototype this spring". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- Dave Mosher (19 November 2018). "NASA 'will eventually retire' its new mega-rocket if SpaceX, Blue Origin can safely launch their own powerful rockets". New Haven Register. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- Matthew Broersma (28 December 2018). "SpaceX Starts Construction Of Mars Rocket Prototype". Silicon.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- "Here are four things we learned from Elon Musk before the first Falcon Heavy launch". 5 February 2018. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- "Huge Mars Colony Eyed by SpaceX Founder". Discovery News. 13 December 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- Bergin, Chris (29 August 2014). "Battle of the Heavyweight Rockets -- SLS could face Exploration Class rival". NASAspaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Berger, Eric (18 September 2016). "Elon Musk scales up his ambitions, considering going "well beyond" Mars". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- "Elon Musk Says SpaceX Will Send Yusaku Maezawa (and Artists!) to the Moon". Wired. 18 September 2018. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Eric Ralph (14 September 2018). "SpaceX has signed a private passenger for the first BFR launch around the Moon". TeslaRati. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- Foust, Jeff (17 November 2018). "Musk hints at further changes in BFR design". SpaceNews. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- D'Agostino, Ryan (22 January 2019). "Elon Musk: Why I'm Building the Starship out of Stainless Steel". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (22 May 2019). "3 sea level optimized Raptors, 3 vacuum optimized Raptors (big nozzle)" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (30 May 2019). "Wings/flaps & leg design changing again (sigh). Doesn't affect schedule much though" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (22 September 2019). "Adding the rear moving fins to Starship Mk1 in Boca Chica, Texas" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Eric Ralph (22 September 2019). "SpaceX installs two Starship wings ahead of Elon Musk's Saturday update". TeslaRati.

- Alan Boyle (22 September 2019). "Elon Musk tweets a sneak peek at his vision for SpaceX's Starship mega-rocket". GeekWire.

- Berger, Eric (26 July 2019). "SpaceX's Starship prototype has taken flight for the first time". Ars Technica. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Foust, Jeff (27 August 2019). "SpaceX's Starhopper completes test flight". SpaceNews. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- Elon Musk (28 September 2019). Starship Update (video). SpaceX. Event occurs at 1:45. Retrieved 30 September 2019 – via YouTube.

- Malik, Tariq (28 September 2019). "Elon Musk Unveils SpaceX's New Starship Plans for Private Trips to the Moon, Mars and Beyond". Space.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- Zafar, Ramish (28 September 2019). "SpaceX's Starship Mk1 Expected To Be Ready For 20km Test In 2 Months". wccftech.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- Matsunaga, Samantha (28 September 2019). "Five things we learned from Elon Musk's rollout of the SpaceX Starship prototype". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "SpaceX's Starship is a new kind of rocket, in every sense". The Economist. 5 October 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Wall, Mike (30 September 2019). "'Totally Nuts'? Elon Musk Aims to Put a Starship in Orbit in 6 Months. Here's SpaceX's Plan". Space.com. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (11 May 2020). "Starship + Super Heavy propellant mass is 4800 tons (78% O2 & 22% CH4). I think we can get propellant cost down to ~$100/ton in volume, so ~$500k/flight. With high flight rate, probably below $1.5M fully burdened cost for 150 tons to orbit or ~$10/kg" (Tweet). Retrieved 19 June 2020 – via Twitter.

- Eric Ralph (2 December 2019). "SpaceX Starship hardware mystery solved amid reports of Florida factory upheaval". TeslaRati. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1221938474233868288?s=20

- https://spacenews.com/second-starship-prototype-damaged-in-pressurization-test/

- Musk, Elon (2 March 2020). "We're stripping SN2 to bare minimum to test the thrust puck to dome weld under pressure, first with water, then at cryo. Hopefully, ready to test in a few days". @elonmusk. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Jeff Foust. "Third Starship prototype destroyed in tanking test". SpaceNews. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Musk, Elon (9 March 2020). "SN2 (with thrust puck) passed cryo pressure & engine thrust load tests late last night". @elonmusk. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Starship SN3 failure due to bad commanding. SN4 already under construction". NASASpaceFlight.com. 5 April 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Ralph, Eric. "SpaceX's Starship rocket just breathed fire for the first time (and survived)". Teslarati. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- https://twitter.com/NASASpaceflight/status/1266442087848960000?s=20

- "Elon Musk tells SpaceX employees that its Starship rocket is the top priority now". CNBC \last=Sheetz. 7 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

|first=missing|last=(help) - Groh, Jamie. "SpaceX debuts Starship's new Super Heavy booster design". Teslarati. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- Musk, Elon (17 March 2019). "Full size".

- Musk, Elon (23 May 2019). "First flights would have fewer, so as to risk less loss of hardware. Probably around 20".

- Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (3 October 2019). "Welded steel" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Groh, Jamie (28 September 2019). "SpaceX debuts Starship's new Super Heavy booster design". Teslarati. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Elon Musk (28 September 2016). "Making Humans a Multiplanetary Species". SpaceX. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Gaynor, Phillip (9 August 2018). "The Evolution of the Big Falcon Rocket". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Musk, Elon (1 March 2018). "Making Life Multi-Planetary". New Space. 6 (1): 2–11. Bibcode:2018NewSp...6....2M. doi:10.1089/space.2018.29013.emu.

- Jeff Foust (15 October 2017). "Musk offers more technical details on BFR system". SpaceNews. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

[Musk wrote,] "The flight engine design is much lighter and tighter, and is extremely focused on reliability."

- "Starship Launch Animation". SpaceX. 14 October 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (26 March 2019). "Yes, otherwise propellant usage for an atmospheric entry would be very high and/or center of mass would need to be very tightly constrained. Yes, but we're going to skip that at first to avoid fragging launch pads" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (7 February 2019). "Prob wise for version 1 to have legs or we will frag a lot of launch pads" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "SpaceX Super Heavy block 1 will have landing legs as Starship".

- Wang, Brian (31 August 2019). "SpaceX Orbital Starship Aiming for 20 Kilometer Flight in October and Orbital Attempt After". Next Big Future. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "Starship users guide" (PDF). Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Orbital refilling is critical for high payload to moon or Mars. Initially just Starship to Starship, later dedicated tankers.", Elon Musk, Twitter, 21 July 2019, accessed 22 July 2019.

- Ralph, Eric (24 December 2018). "SpaceX CEO Elon Musk: Starship prototype to have 3 Raptors and "mirror finish"". Teslarati. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- A conversation with Elon Musk about Starship, Tim Dodd, 1 October 2019, accessed 12 June 2020.

- https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1015648140341403648, Elon Musk, 18 July 2018, accessed 12 June 2020.

- Could do it, but we developed low cost reusable tiles that are much lighter than transpiration cooling & quite robust, Elon Musk, 24 September 2019, accessed 24 September 2019.

- Thin tiles on windward side of ship & nothing on leeward or anywhere on booster looks like lightest option, Elon Musk, 24 July 2019, accessed 25 July 2019.

- Gebhardt, Chris (3 April 2019). "Starhopper conducts Raptor Static Fire test". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- SpaceX Starship Will "Bleed Water" From Tiny Holes, Says Elon Musk. Kristin Houser, Futurism. 22 January 2019.

- Eric Ralph (23 January 2019). "SpaceX CEO Elon Musk explains Starship's "transpiring" steel heat shield in Q&A". Teslarati.

- Ralph, Eric. "SpaceX tests ceramic Starship heat shield tiles on Starhopper's final flight test". Teslarati. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Paul Wooster (20 October 2019). SpaceX - Mars Society Convention 2019 (video). Event occurs at 47:30-49:00. Retrieved 25 October 2019 – via YouTube.

Vehicle is designed to be able to land at the Earth, Moon or Mars. Depending on which ... the ratio of the energy dissipated aerodynamically vs. propulsively is quite different. In the case of the Moon, it's entirely propulsive. ... Earth: over 99.9% of the energy is removed aerodynamically ... Mars: over 99% of the energy is being removed aerodynamically at Mars.

- Ralph, Eric (1 April 2019). "SpaceX CEO Elon Musk proposes Starship, Starlink tech for Solar System tour". Teslarati. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Elon Musk wants to move fast with SpaceX’s Starship. Stephen Clarke, Space Flight Now. 29 September 2019.

- SpaceX's Big Starship Reveal Raised More Questions Than Answers. Jonathan O'Callaghan, Forbes. 30 September 2019.

- Elon Musk Unveils His Starship, Plans to Fly It in a Matter of Months. Joel Hruska, Extreme Tech. 30 September 2019.

- Cummings, Nick (11 June 2020). Human Landing System: Putting Boots Back on the Moon. American Astronautical Society. Event occurs at 35:00–36:02. Retrieved 12 June 2020 – via YouTube.

for the terminal descent of Starship, a few tens of meters before we touch down on the lunar surface, we actually use a high-thrust RCS system, so that we don't impinge on the surface of the Moon with the high=thrust Raptor engines. ... uses the same methane and oxygen propellants as Raptor.

- Musk, Elon. Twitter https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1270061515094155264?s=20. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "NASA Selects Blue Origin, Dynetics, and SpaceX Human Landers for Artemis". NASASpaceFlight.com. 1 May 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Potter, Sean (30 April 2020). "NASA Names Companies to Develop Human Landers for Artemis Missions". NASA. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Berger, Eric (30 April 2020). "NASA awards lunar lander contracts to Blue Origin, Dynetics—and Starship". Ars Technica. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- SpaceX considering SSTO Starship launches from Pad 39A, Michael Baylor, NASASpaceFlight.com, 17 May 2019, accessed 18 May 2019.

- Burghardt, Thomas (25 July 2019). "Starhopper successfully conducts debut Boca Chica Hop". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (22 May 2019). "Mk1 & Mk2 ships at Boca & Cape will fly with at least 3 engines, maybe all 6" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Commercial Space Transportation Experimental Permit -- Experimental Permit Number: EP19-012, FAA, 21 June 2019, accessed 29 June 2019.

- Ralph, Eric (12 March 2019). "SpaceX begins static Starhopper tests as Raptor engine arrives on schedule". Teslarati. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Gebhardt, Chris (18 March 2019). "Starhopper first flight as early as this week; Starship/Superheavy updates". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Musk, Elon (6 February 2020). "Unmodified water tower machines do not work well for orbital rockets, as mass efficiency is critical for the latter, but not the former. Hopper, for example, was made of 12.5mm steel vs 4mm for SN1 orbital design. Optimized skins will be". @elonmusk. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- Berger, Eric (8 January 2019). "Here's why Elon Musk is tweeting constantly about a stainless-steel starship". Ars Technica. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- Baylor, Michael (2 June 2019). "SpaceX readying Starhopper for hops in Texas as Pad 39A plans materialize in Florida". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Ralph, Eric (9 March 2019). "SpaceX's Starship prototype moved to launch pad on new rocket transporter". Teslarati. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Baylor, Michael (27 August 2019). "SpaceX's Starhopper completes 150 meter test hop". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (22 December 2018). "We're building subsections of the Starship Mk I orbital design there [in San Pedro]" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (10 January 2019). "Should be done with first orbital prototype around June" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Kanter, Jake (11 January 2019). "Elon Musk released a photo of his latest rocket, and it already delivers on his promise of looking like liquid silver". Business Insider. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- 'Totally Nuts'? Elon Musk Aims to Put a Starship in Orbit in 6 Months. Here's SpaceX's Plan. Mike Wall, Space.com. 30 September 2019.

- "Watch SpaceX's Starship Mk1 partially explode during test". cnn.com. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Grush, Loren (20 November 2019). "SpaceX's prototype Starship rocket partially bursts during testing in Texas". The Verge. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Spaceflight, Mike Wall 2019-11-20T23:16:59Z. "SpaceX's 1st Full-Size Starship Prototype Suffers Anomaly in Pressure Test". Space.com. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- https://www.cnbc.com/2019/10/17/spacex-starts-construction-of-another-starship-rocket-in-florida.html, CNBC, 17 October 2019, accessed 18 October 2019.

- https://spaceflightnow.com/2019/12/05/spacex-pausing-some-starship-work-in-florida/, Spaceflightnow.com, December 25, 2019, accessed June 27 2020.

- "SpaceX Starship hardware mystery solved amid reports of Florida factory upheaval". 2 December 2019.

- "SpaceX's Starship SN1 prototype appears to burst during pressure test". Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- "Starship SN3 failure due to bad commanding. SN4 already under construction". NASASpaceFlight.com. 5 April 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Starship passes key pressurization test". spacenews.com. 27 April 2020.

- Jeff Foust (15 October 2017). "Musk offers more technical details on BFR system". SpaceNews. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

[The] spaceship portion of the BFR, which would transport people on point-to-point suborbital flights or on missions to the moon or Mars, will be tested on Earth first in a series of short hops. ... a full-scale Ship doing short hops of a few hundred kilometers altitude and lateral distance ... fairly easy on the vehicle, as no heat shield is needed, we can have a large amount of reserve propellant and don't need the high area ratio, deep space Raptor engines.

- Foust, Jeff (12 March 2018). "Musk reiterates plans for testing BFR". SpaceNews. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

Construction of the first prototype spaceship is in progress. 'We're actually building that ship right now,' he said. 'I think we'll probably be able to do short flights, short sort of up-and-down flights, probably sometime in the first half of next year.'

- "SpaceX's Starship hopper steps towards first hop with several cautious tests". Teslarati. 29 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Foust, Jeff (24 December 2018). "Musk teases new details about redesigned next-generation launch system". SpaceNews. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- Grush, Loren (3 April 2019). "SpaceX just fired up the engine on its test Starship vehicle for the first time". The Verge. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Bergin, Chris [@NASASpaceflight] (5 April 2019). "StarHopper enjoys second Raptor Static Fire!" (Tweet). Retrieved 23 May 2019 – via Twitter.

- "Commercial Space Transportation Experimental Permit, No. EP19-012" (PDF). Office of Commercial Space Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration. 21 June 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- "SpaceX StarHopper engine test and unexpected fireball (4K Slow Mo)" – via www.youtube.com.

- "FAA | Commercial Space Data | Permitted Launches". Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Starship Hopper Causes Massive Fire!!!" – via www.youtube.com.

- Berger, Eric (26 July 2019). "SpaceX's Starship prototype has taken flight for the first time". Ars Technica. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Ralph, Eric (27 August 2019). "SpaceX scrubs Starhopper's final Raptor-powered flight as Elon Musk talks 'finicky' igniters". Teslarati. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "SpaceX Starhopper Rocket Prototype Aces Highest (and Final) Test Flight". Space. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- 150 Meter Starhopper Test. SpaceX. 27 August 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019 – via YouTube.

- Mosher, Dave (7 August 2019). "SpaceX may 'cannibalize' its first Mars rocket-ship prototype in Elon Musk's race to launch Starship". Business Insider. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- SpaceX Launch Control Center LIVE: Starlink Launch, Mission updates. SpaceX. 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020 – via YouTube.

- "Elon Musk says SpaceX's Starship could fly for as little as $2 million per launch". 6 November 2019.

- Smith, Rich (8 December 2018). "A Renamed BFR Could Be Key to SpaceX's Satellite Internet Dream". The Motley Fool. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (12 May 2018). "SpaceX will prob build 30 to 40 rocket cores for ~300 missions over 5 years. Then BFR takes over & Falcon retires. Goal of BFR is to enable anyone to move to moon, Mars & eventually outer planets" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Sheetz, Michael (18 March 2019). "Super fast travel using outer space could be $20 billion market, disrupting airlines, UBS predicts". CNBC. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Elon Musk (28 September 2017). Starship | Earth to Earth (video). SpaceX. Event occurs at 1:45. Retrieved 30 March 2019 – via YouTube.

- Neil Strauss (15 November 2017). "Elon Musk: The Architect of Tomorrow". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Ralph, Eric (30 May 2019). "SpaceX CEO Elon Musk wants to use Starships as Earth-to-Earth transports". Teslarati. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- Mosher, Dave (16 June 2020). "Elon Musk: 'SpaceX is building floating, superheavy-class spaceports' for its Starship rocket to reach the moon, Mars, and fly passengers around Earth". Business Insider. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Bergin, Chris; Gebhardt, Chris (27 September 2016). "SpaceX reveals ITS Mars game changer via colonization plan". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- https://twitter.com/SpcPlcyOnline/status/780894498893225984

- The biggest lingering questions about SpaceX's Mars colonization plans. Loren Grush, The Verge. 28 September 2016. Quote: "The radiation thing is often brought up, but I think it's not too big of a deal."

- SpaceX is quietly planning Mars-landing missions with the help of NASA and other spaceflight experts. It's about time. Dave Mosher, Business Insider. 11 August 2018. Quote: "Keeping the human body healthy in space is another challenge that Porterfield said SpaceX needs to figure out."

- Elon Musk's future Starship updates could use more details on human health and survival. Loren Grush, The Verge. 4 October 2019,

- Elon Musk Still Isn't Answering The Most Important Questions About Mars. Rae Paoletta, The Inverse. 29 September 2017.

- What SpaceX Needs to Accomplish Before Colonizing Mars. Neel V. Patel, The Inverse. 30 June 2016. Quote: "Space radiation is perhaps the biggest issue at play, and it's not quite clear if Musk has a good understanding of how it works and the extent to which it's stopping us from sending astronauts to far off worlds. […] For Musk and his colleagues to move forward and simply disregard the problem posed by cosmic rays would be insanely irresponsible."

- Elon Musk's Starship may be more moral catastrophe than bold step in space exploration. Samantha Rolfe, University Of Hertfordshire, The Conversation. 2 October 2019. Quote: "I'm not sure that it is fair or ethical to expect astronauts to be exposed to dangerous levels of radiation that could leave them with considerable health problems—or worse, imminent death."

- Elon Musk Should Read This Study About Space Radiation — or Fail Miserably. Rae Paoletta, The Verge. 16 March 2018.

- Musk Reads: Elon Musk hints at first Starship payload. Mike Brown, The Inverse. 8 October 2019.

- The first Mars settlers may get blasted with radiation levels 8 times higher than government limits allow. Skye Gould and Dave Mosher, Business Insider. Quote: "Ambient radiation damage is not significant for our transit times" -Elon Musk.

- SpaceX’s Elon Musk explains how his big rocket's short hops will lead to giant leaps. Alan Boyle, Geek Wire. 14 October 2019. Quote: "Ambient radiation damage is not significant for our transit times," Musk replied. "Just need a solar storm shelter, which is a small part of the ship."

.svg.png)