Multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator

The multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) is a type of radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) developed for NASA space missions[1] such as the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Energy's Office of Space and Defense Power Systems within the Office of Nuclear Energy. The MMRTG was developed by an industry team of Aerojet Rocketdyne and Teledyne Energy Systems.

Background

Space exploration missions require safe, reliable, long-lived power systems to provide electricity and heat to spacecraft and their science instruments. A uniquely capable source of power is the radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) – essentially a nuclear battery that reliably converts heat into electricity.[2] Radioisotope power has been used on eight Earth orbiting missions, eight missions to the outer planets, and the Apollo missions after Apollo 11 to Earth's moon. The outer Solar System missions are the Pioneer 10 and 11, Voyager 1 and 2, Ulysses, Galileo, Cassini and New Horizons missions. The RTGs on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 have been operating since 1977.[3] In total, over the last four decades, 26 missions and 45 RTGs have been launched by the United States.

Function

Solid-state thermoelectric couples convert the heat from the natural decay of the radioisotope plutonium-238 dioxide to electricity.[4] Unlike solar arrays, RTGs are not dependent upon the Sun, so they can be used for deep space missions.

History

In June 2003, the Department of Energy (DOE) awarded the MMRTG contract to a team led by Aerojet Rocketdyne. Aerojet Rocketdyne and Teledyne Energy Systems collaborated on an MMRTG design concept based on a previous thermoelectric converter design, SNAP-19, developed by Teledyne for previous space exploration missions.[5] SNAP-19s powered Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 missions[4] as well as the Viking 1 and Viking 2 landers.

Design and specifications

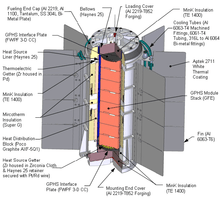

The MMRTG is powered by eight Pu-238 dioxide general-purpose heat source (GPHS) modules, provided by the Department of Energy. Initially, these eight GPHS modules generate about 2 kW thermal power.

The MMRTG design incorporates PbTe/TAGS thermoelectric couples (from Teledyne Energy Systems), where the TAGS material is a material incorporating Tellurium (Te), Silver (Ag), Germanium (Ge) and Antimony (Sb). The MMRTG is designed to produce 125 W electrical power at the start of mission, falling to about 100 W after 14 years.[6] With a mass of 45 kg[7] the MMRTG provides about 2.8 W/kg of electrical power at beginning of life.

The MMRTG design is capable of operating both in the vacuum of space and in planetary atmospheres, such as on the surface of Mars. Design goals for the MMRTG included ensuring a high degree of safety, optimizing power levels over a minimum lifetime of 14 years, and minimizing weight.[2]

Usage in space missions

Curiosity, the MSL rover that was successfully landed in Gale Crater on August 6, 2012, uses one MMRTG to supply heat and electricity for its components and science instruments. Reliable power from the MMRTG will allow it to operate for several years.[2]

On February 20, 2015, a NASA official reported that there is enough plutonium available to NASA to fuel three more MMRTG like the one used by the Curiosity rover.[8][9] One is already committed to the Mars 2020 rover.[8] The other two have not been assigned to any specific mission or program,[9] and could be available by late 2021.[8]

See also

References

- "Radioisotope Power Systems for Space Exploration" (PDF). March 2011. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

-

- Bechtel, Ryan. "Radioisotope Missions" (PDF). US Department of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-01.

- SNAP-19: Pioneer F & G, Final Report, Teledyne Isotopes, 1973

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-16. Retrieved 2011-11-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://pdf.aiaa.org/preview/CDReadyMIECEC06_1309/PV2006_4187.pdf

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2013-04-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Leone, Dan (11 March 2015). "U.S. Plutonium Stockpile Good for Two More Nuclear Batteries after Mars 2020". Space News. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- Moore, Trent (12 March 2015). "NASA can only make three more batteries like the one that powers the Mars rover". Blastr. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Radioisotope thermoelectric generators. |

- NASA Radioisotope Power Systems website – RTG page

- Idaho National Laboratory MMRTG page with photo-based "virtual tour"

- DOE to Crank Out New Plutonium 238 in 2019