Mariner program

The Mariner program was a 10-mission program conducted by the American space agency NASA in conjunction with Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).[1] The program launched a series of robotic interplanetary probes, from 1962 to 1973, designed to investigate Mars, Venus and Mercury.[2] The program included a number of firsts, including the first planetary flyby, the first planetary orbiter, and the first gravity assist maneuver.

Of the ten vehicles in the Mariner series, seven were successful, forming the starting point for many subsequent NASA/JPL space probe programs. The planned Mariner Jupiter-Saturn vehicles were adapted into the Voyager program,[3] while the Viking program orbiters were enlarged versions of the Mariner 9 spacecraft. Later Mariner-based spacecraft include the Magellan probe and the Galileo probe, while the second-generation Mariner Mark II series evolved into the Cassini–Huygens probe.

The total cost of the Mariner program was approximately $554 million.[4]

The name of the Mariner program was decided in "May 1960-at the suggestion of Edgar M. Cortright" to have the "planetary mission probes ... patterned after nautical terms, to convey 'the impression of travel to great distances and remote lands.'" That "decision was the basis for naming Mariner, Ranger, Surveyor, and Viking probes."[5]

Basic layout

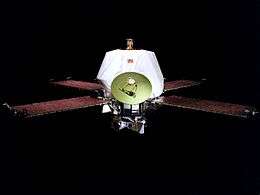

All Mariner spacecraft were based on a hexagonal or octagonal "bus", which housed all of the electronics, and to which all components were attached, such as antennae, cameras, propulsion, and power sources.[2][6] Mariner 2 was based on the Ranger Lunar probe. All of the Mariners launched after Mariner 2 had four solar panels for power, except for Mariner 10, which had two. Additionally, all except Mariner 1, Mariner 2 and Mariner 5 had TV cameras.

The first five Mariners were launched on Atlas-Agena rockets, while the last five used the Atlas-Centaur. All Mariner-based probes after Mariner 10 used the Titan IIIE, Titan IV unmanned rockets or the Space Shuttle with a solid-fueled Inertial Upper Stage and multiple planetary flybys.

- Mariners

- Mariner 1, first spacecraft of the Mariner program, designed for a planetary flyby of Venus - Launched on July 22, 1962

- Mariner 2, space probe to Venus, the first robotic space probe to conduct a successful planetary encounter - Launched on August 27, 1962

- Mariner 3, one of two identical deep-space probes designed for close-up observations of Mars - Launched on November 5, 1964

- Mariner 4, second of two identical deep-space probes designed for close-up observations of Mars - Launched on November 28, 1964

- Mariner 5, spacecraft to measure magnetic fields and various emissions of the Venusian atmosphere - Launched on June 14, 1967

- Mariner 6 and 7, two unmanned NASA space probes that completed the first dual mission to Mars - Launched on February 25, 1969

- Mariner 8, one of two probes designed to orbit Mars and return images and data - Launched on May 9, 1971 but lost in a vehicle malfunction

- Mariner 9, second of two probes designed to orbit Mars and return images - Launched successfully on May 30, 1971

- Mariner 10, last of the Mariner probes; designed to fly by Mercury and Venus - Launched on November 3, 1973

Mariners 1 and 2

Mariner 1 (P-37) and Mariner 2 (P-38) were two deep-space probes making up NASA's Mariner-R project. The primary goal of the project was to develop and launch two spacecraft sequentially to the near vicinity of Venus, receive communications from the spacecraft and to perform radiometric temperature measurements of the planet. A secondary objective was to make interplanetary magnetic field and/or particle measurements on the way to, and in the vicinity of, Venus.[7][8] Mariner 1 (designated Mariner R-1) was launched on July 22, 1962, but was destroyed approximately 5 minutes after liftoff by the Air Force Range Safety Officer when its malfunctioning Atlas-Agena rocket went off course. Mariner 2 (designated Mariner R-2) was launched on August 27, 1962, sending it on a 3½-month flight to Venus. The mission was a success, and Mariner 2 became the first spacecraft to have flown by another planet.

- Mission: Venus flyby

- weight: 203 kg (446 lb)

- Sensors: microwave and infrared radiometers, cosmic dust, solar plasma and high-energy radiation, magnetic fields

Status:

- Mariner 1 – Destroyed shortly after liftoff.

- Mariner 2 – Defunct after successful mission, occupies a heliocentric orbit.

Mariners 3 and 4

Sisterships Mariner 3 and Mariner 4 were Mars flyby missions.[9]

Mariner 3 was lost when the launch vehicle's nose fairing failed to jettison.

Mariner 4, launched on November 28, 1964, was the first successful flyby of the planet Mars and gave the first glimpse of Mars at close range.[9]

- Mission: Mars flyby[9]

- Mass: 261 kg (575 lb)

- Sensors: camera with digital tape recorder (about 20 pictures), cosmic dust, solar plasma, trapped radiation, cosmic rays, magnetic fields, radio occultation and celestial mechanics[10]

Status:

- Mariner 3 – Malfunctioned. Derelict in heliocentric orbit.[9]

- Mariner 4 – Communications lost after bombardment by micrometeoroids. Derelict in heliocentric orbit.[10]

Mariner 5

The Mariner 5 spacecraft was launched to Venus on June 14, 1967 and arrived in the vicinity of the planet in October 1967. It carried a complement of experiments to probe Venus' atmosphere with radio waves, scan its brightness in ultraviolet light, and sample the solar particles and magnetic field fluctuations above the planet.

- Mission: Venus flyby

- Mass: 245 kg (540 lb)

- Sensors: ultraviolet photometer, cosmic dust, solar plasma, trapped radiation, cosmic rays, magnetic fields, radio occultation and celestial mechanics

Status: Mariner 5 – Defunct. Now in Heliocentric orbit.

Mariners 6 and 7

Mariners 6 and 7 were identical teammates in a two-spacecraft mission to Mars. Mariner 6 was launched on February 24, 1969, followed by Mariner 7 on March 21, 1969. They flew over the equator and southern hemisphere of the planet Mars.[11]

- Mission: Mars flybys

- Mass 413 kg (908 lb)

- Sensors: wide- and narrow-angle cameras with digital tape recorder, infrared spectrometer and radiometer, ultraviolet spectrometer, radio occultation and celestial mechanics.

Status: Both Mariner 6 and Mariner 7 are now defunct and are in a Heliocentric orbit.[11]

Mariners 8 and 9

Mariner 8 and Mariner 9 were identical sister craft designed to map the Martian surface simultaneously, but Mariner 8 was lost in a launch vehicle failure. Mariner 9 was launched in May 1971 and became the first artificial satellite of Mars. It entered Martian orbit in November 1971 and began photographing the surface and analyzing the atmosphere with its infrared and ultraviolet instruments.

- Mission: orbit Mars

- Mass 998 kg (2,200 lb)

- Sensors: wide- and narrow-angle cameras with digital tape recorder, infrared spectrometer and radiometer, ultraviolet spectrometer, radio occultation and celestial mechanics

Status:

- Mariner 8 – Destroyed in a launch vehicle failure.

- Mariner 9 – Shut off. In Areocentric (Mars) orbit until at least 2022 when it is projected to fall out of orbit and into the Martian atmosphere.[12]

Mariner 10

The Mariner 10 spacecraft launched on November 3, 1973 and was the first to use a gravity assist trajectory, accelerating as it entered the gravitational influence of Venus, then being flung by the planet's gravity onto a slightly different course to reach Mercury. It was also the first spacecraft to encounter two planets at close range, and for 33 years the only spacecraft to photograph Mercury in closeup.

- Mission: plasma, charged particles, magnetic fields, radio occultation and celestial mechanics

Status: Mariner 10 – Defunct. Now in a Heliocentric orbit.

Mariner Jupiter-Saturn

Mariner Jupiter-Saturn was approved in 1972 after the cancellation of the Grand Tour program, which proposed visiting all the outer planets with multiple spacecraft. The Mariner Jupiter-Saturn program proposed two Mariner-derived probes that would perform a scaled back mission involving flybys of only the two gas giants, though designers at JPL built the craft with the intention that further encounters past Saturn would be an option. Trajectories were chosen to allow one probe to visit Jupiter and Saturn first, and perform a flyby of Saturn's moon Titan to gather information about the moon's substantial atmosphere. The other probe would arrive at Jupiter and Saturn later, and its trajectory would enable it to continue on to Uranus and Neptune assuming the first probe accomplished all its objectives, or be redirected to perform a Titan flyby if necessary. The program's name was changed to Voyager just before launch in 1977, and after Voyager 1 successfully completed its Titan encounter, Voyager 2 went on to visit the two ice giants.[3]

References

- "Mariner-Venus 1962 Final Project Report" (PDF). NASA Technical Reports Server. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- "Mariner Program". JPL Mission and Spacecraft Library. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- Chapter 11 "Voyager: The Grand Tour of Big Science" (sec. 268.), by Andrew,J. Butrica, found in From Engineering Science To Big Science ISBN 978-0-16-049640-0 edited by Pamela E. Mack, NASA, 1998

- Mariner 4, NSSDC Master Catalog

- SP-4402 Origins of NASA Names

- "Untitled" (PDF). NASA Technical Reports Server. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- "Tracking Information Memorandom: Mariner R 1 and 2" (PDF). NASA Technical Reports Server. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- "Mariner R Spacecraft for Missions P-37/P-38" (PDF). NASA Technical Reports Server. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

-

Pyle, Rod (2012). Destination Mars. Prometheus Books. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-61614-589-7.

Mariner 3, dead and still ensnared in its faulty launch shroud, in a large orbit around the sun.

-

Pyle, Rod (2012). Destination Mars. Prometheus Books. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-61614-589-7.

It eventually joined its sibling, Mariner 3, dead ... in a large orbit around the sun.

- Pyle, Rod (2012). Destination Mars. Prometheus Books. pp. 61–66. ISBN 978-1-61614-589-7.

- NASA - This Month in NASA History: Mariner 9 Archived May 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, November 29, 2011 — Vol. 4, Issue 9