Mars sample-return mission

A Mars Sample-Return (MSR) mission would be a spaceflight mission to collect rock and dust samples on Mars and then return them to Earth. Sample-return would be a very powerful type of exploration, because the analysis is freed from the time, budget, and space constraints of spacecraft sensors.[1]

According to Louis Friedman, Executive Director of The Planetary Society, a Mars sample-return mission is often described by the planetary science community as one of the most important robotic space missions, due to its high expected scientific return on investment[2] and its ability to prove the technology needed for a human mission to Mars.

Over time, several concept missions have been studied, but none of them got beyond the study phase. The three latest concepts for an MSR mission are a NASA-ESA proposal, a Russian proposal (Mars-Grunt), and a Chinese proposal.

Scientific value

.jpg)

The return of Mars samples would benefit science by allowing more extensive analysis to be undertaken of the samples than could be done by instruments painstakingly transferred to Mars. Also, the presence of the samples on Earth would allow scientific equipment to be used on stored samples, even years and decades after the sample-return mission.[3]

In 2006, MEPAG identified 55 important future science investigations related to the exploration of Mars. In 2008, they concluded that about half of the investigations "could be addressed to one degree or another by MSR", making MSR "the single mission that would make the most progress towards the entire list" of investigations. Moreover, it was found that a significant fraction of the investigations cannot be meaningfully advanced without returned samples.[4]

One source of Mars samples is what are thought to be Martian meteorites, which are rocks ejected from Mars that made their way to Earth. Of over 61,000 meteorites that have been found on Earth, 132 were identified as Martian as of 3 March 2014.[5] These meteorites are thought to be from Mars because they have elemental and isotopic compositions that are similar to rocks and atmosphere gases analyzed by spacecraft on Mars.[6]

In 1996, the possibility of life on Mars was questioned again when apparent microfossils might have been found in a Mars meteorite (see ALH84001).[7] This led to a renewed interest in a Mars sample-return, and several different architectures were considered.[7] NASA administrator Goldin laid out three options for MSR: "paced", "accelerated", and "aggressive".[7] It was thought that MSR could be done for less than US$100 million per year, with something similar to then-current Mars exploration budgets.[7]

History

For at least three decades, Western scientists have advocated the return of geological samples from Mars.[8] One concept was studied with the Sample Collection for Investigation of Mars (SCIM) proposal, which involved sending a spacecraft in a grazing pass through Mars upper atmosphere to collect dust and air samples without landing or orbiting.[9]

The Soviet Union considered a Mars sample-return mission, Mars 5NM, in 1975 but it was cancelled due to the repeated failures of the N1 rocket that would have been used to launch it. A double sample-return mission, Mars 5M (Mars-79) planned for 1979, was cancelled due to complexity and technical problems.

One mission concept (provisionally named simply Mars Sample-Return) was originally considered by NASA's Mars Exploration Program to return samples by 2008,[10] but was cancelled following a review of the program.[11] In the summer of 2001, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) requested mission concepts and proposals from industry-led teams (specifically Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and TRW). That following winter, JPL made similar requests of certain university aerospace engineering departments (namely both MIT and the University of Michigan). A decade later, a NASA-ESA concept mission was aborted in 2012.[12]

The United States' Mars Exploration Program, formed after Mars Observer's failure in September 1992,[13] supported a Mars sample-return.[13] One example of a mission architecture was the Groundbreaking Mars Sample-Return by Glenn J. MacPherson in the early 2000s.[14]

In early 2011, the National Research Council's Planetary Science Decadal Survey, which laid out mission planning priorities for the period 2013–2022 at the request of NASA and the NSF, declared a MSR campaign its highest priority Flagship Mission for that period.[15] In particular, it endorsed the proposed Mars Astrobiology Explorer-Cacher (MAX-C) mission in a "descoped" (less ambitious) form, although this mission plan was officially cancelled in April 2011.

In September 2012, the United States' Mars Program Planning Group endorsed a sample-return after evaluating long-term Mars' plans.[16][17]

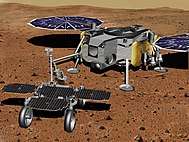

The key mission requirement for the planned Perseverance rover is that it must help prepare NASA for its MSR campaign,[18][19][20] which is needed before any crewed mission takes place.[21][22][23] Such effort would require three additional vehicles: an orbiter, a fetch rover, and a Mars ascent vehicle (MAV). In April 2020, an updated version of the mission was presented.[24]

(animated video; 02:22; 6 February 2020)

NASA–ESA concept

In mid-2006, the International Mars Architecture for the Return of Samples (iMARS) Working Group was chartered by the International Mars Exploration Working Group (IMEWG) to outline the scientific and engineering requirements of an internationally sponsored and executed Mars sample-return mission in the 2018–2023 time frame.[4]

In October 2009, NASA and ESA established the Mars Exploration Joint Initiative to proceed with the ExoMars program, whose ultimate aim is "the return of samples from Mars in the 2020s".[28][29] ExoMars' first mission would launch in 2018[3][30] with unspecified missions to return samples in the 2020–2022 time frame.[31] The cancellation of the caching rover MAX-C, and later NASA withdrawal from ExoMars, pushed back a sample-return mission to an undetermined date. Due to budget limitations the MAX-C mission was canceled in 2011, and the overall cooperation in 2012.[12] The pull-out was described as "traumatic" for the science community.[12]

In April 2018, a letter of intent was signed by NASA and ESA that may provide a basis for a Mars sample-return mission.[32][33] In July 2019, a mission architecture was proposed to return samples to Earth by 2032:[34][35] In April 2020, an updated version of the mission was presented.[24]

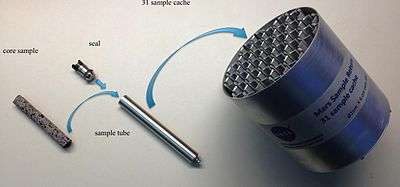

- The Perseverance rover will collect samples and leave them behind on the surface for later retrieval.

- After a launch in July 2026, a lander with a Mars ascent rocket (developed by NASA) and a sample collection rover (developed by ESA) lands near the Mars 2020 rover in August 2028. The new rover collects the samples left behind by Mars 2020 and delivers them to the ascent rocket. If Mars 2020 is still operational it could also deliver samples to the landing site. Once loaded with the samples, the Mars ascent rocket will launch with the sample return canister in spring 2029 and reach a low Mars orbit.

- The ESA-built Earth-return orbiter launches on an Ariane 6 booster in October 2026 and arrives at Mars in 2027, using ion propulsion to gradually lower its orbit to the proper altitude by July 2028. The orbiter will retrieve the canister with the samples in orbit and return it to Earth during the 2031 Mars-to-Earth transfer window.

- The sample return canister, encapsulated within the Earth re-entry module, lands on Earth in spring 2032.

NASA proposals

In September 2012, NASA announced its intention to further study several strategies of bringing a sample of Mars to Earth – including a multiple launch scenario, a single-launch scenario, and a multiple-rover scenario – for a mission beginning as early as 2018.[36] Dozens of samples would be collected and cached by the Mars 2020 rover, and would be left on the surface of Mars for possible later retrieval.[20] A "fetch rover" would retrieve the sample caches and deliver them to a Mars ascent vehicle (MAV). In July 2018 NASA contracted Airbus to produce a "fetch rover" concept.[37]

The MAV would launch from Mars and enter a 500 km orbit and rendezvous with a new Mars orbiter.[20] The sample container would be transferred to an Earth entry vehicle (EEV) which would bring it to Earth, enter the atmosphere under a parachute and hard-land for retrieval and analyses in specially designed safe laboratories.[19][20]

Two-launches architecture

In this scenario, the sample-return mission would span two launches at an interval of about four years. The first launch would be for the orbiter, the second for the lander.[38] The lander would include the Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV).

Three-launches architecture

This concept would have the sample-return mission split into a total of three launches.[38] In this scenario, the sample-collection rover (e.g. Mars 2020 rover) would be launched separately to land on Mars first, and carry out analyses and sample collection over a lifetime of at least 500 Sols (Martian days).[39]

Some years later, a Mars orbiter would be launched, followed by a lander carrying the Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV). The lander would bring a small and simple "fetch rover", whose sole function would be to retrieve the sample containers from the caches left on the surface or directly from the Perseverance rover, and return them to the lander where it would be loaded onto the MAV for delivery to the orbiter and then be sent to Earth.[40][41]

This design would ease the schedule of the whole project, giving controllers time and flexibility to carry out the required operations. Furthermore, the program could rely on the successful landing system developed for the Mars Science Laboratory, avoiding the costs and risks associated with developing and testing yet another landing system from scratch.[38]

SCIM

SCIM (Sample Collection for Investigation of Mars) was a low-cost low-risk Mars sample-return mission design, proposed in the Mars Scout Program.[9] SCIM would return dust and air samples without landing or orbiting,[9] by dipping through the atmosphere as it collects Mars material.[42] It uses heritage from the successful Stardust and Genesis sample-return missions.[42]

Mars Future Missions

Supports the development of the Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission that is planning to enter formulation (Phase A) as early as the summer of FY 2020. In FY 2021, MSR formulation activities include concept and technology development, and early design and studies in support of the Sample Return Lander and the Capture/Containment and Return System. It also supports a study of the facility required for the handling of returned samples. In developing concepts for a Mars Sample Return mission, the future budget supports an estimated MSR launch readiness date of 2026. Also included is funding for potential collaboration with Canada on the Mars Ice Mapper. The Mars Ice Mapper is a remote sensing mission under study intended to map and profile the near-surface (3–15 meters) water ice, particularly that which lies in the mid-latitude regions, in support of future science and exploration missions.[43]

Additional plans

China

China is considering a Mars sample-return mission by 2030.[44][45] The plan as of 2017 is to launch a large spacecraft that can carry out all phases of the mission, including sample collection, ascent from Mars, rendezvous in Mars orbit, and a flight back to Earth. Such a mission would require the super-heavy-lift Long March 9 rocket.[45][46][47] The needed technologies are to be tested during the HX-1 mission launching in 2020.[46][47] An alternative plan announced in 2019 involves using the 2020 HX-1 mission to cache the samples for retrieval in 2030.[48] These samples would be retrieved by a sample collection lander with Mars ascent vehicle launched in November 2028 on a Long March 3B, and collected in Mars orbit using an Earth Return Orbiter launched on a Long March 5 also in November 2028, with return to Earth in September 2031.[49]

France

France has worked towards a sample-return for many years.[50] This included concepts of an extraterrestrial sample curation facility for returned samples, and numerous proposals.[50] They worked on the development of a Mars sample-return orbiter, which would capture and return the samples as part of a joint mission with either the United States or other European countries.[50]

Japan

On 9 June 2015, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) unveiled a plan named Martian Moons Exploration (MMX) to retrieve samples from one of the moons of Mars.[51] This mission will build on the expertise to be gained from the Hayabusa 2 and SLIM missions.[52] Of the two moons, Phobos's orbit is closer to Mars and its surface may have adhered particles blasted from the red planet; thus the Phobos samples collected by MMX may contain material originating from Mars itself.[53] Japan has also shown interest in participating in an international Mars sample-return mission.

Russia

A Russian Mars sample-return mission concept is Mars-Grunt.[54][55][56][57][58] It is meant to use Fobos-Grunt design heritage.[55] Plans as of 2011 envisioned a two-stage architecture with an orbiter and a lander (but no roving capability),[59] with samples gathered from the immediate surroundings of the lander by a robotic arm.[54][60]

Potential for back contamination

Since it is currently unknown whether life forms exist on Mars, the mission could potentially transfer viable organisms resulting in back contamination—the introduction of extraterrestrial organisms into Earth's biosphere. The scientific consensus is that the potential for large-scale effects, either through pathogenesis or ecological disruption, is extremely small.[61][62][63][64][65] Returned samples from Mars will be treated as potentially biohazardous until scientists can determine that the returned samples are safe. The goal is to reduce the probability of release of a Mars particle to less than one in a million.[62]

The proposed NASA Mars sample-return mission will not be approved by NASA until the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process has been completed.[66] Furthermore, under the terms of Article VII of the Outer Space Treaty and probably various other legal frameworks, were a release of organisms to occur, the releasing nation or nations would be liable for any resultant damages.[67]

Part of the sample-return mission would be to prevent contact between the Martian environment and the exterior of the sample container.[62][66] In order to eliminate the risk of parachute failure, the current plan is to use the thermal protection system to cushion the capsule upon impact (at terminal velocity). The sample container will be designed to withstand the force of the impact.[66] To receive the returned samples, NASA proposed a specially designed Biosafety Level 4 containment facility, the Mars Sample-Return Receiving facility (MSRRF).[68] Not knowing what properties (e.g., size) any Martian organisms might exhibit is a complication in design of such a facility.[69]

Other scientists and engineers, notably Robert Zubrin of the Mars Society, argued in the fringe Journal of Cosmology that contamination risk is functionally zero and there is little need to worry. They cite, among other things, lack of any verifiable incident although trillions of kilograms of material have been exchanged between Mars and Earth due to meteorite impacts.[70]

The International Committee Against Mars Sample Return (ICAMSR) is a small advocacy group led by Barry DiGregorio, who campaigns against a Mars sample-return mission. While ICAMSR acknowledges a low probability for biohazards, it considers the proposed containment measures insufficient, and unsafe at this stage. ICAMSR is demanding more in situ studies on Mars first, and preliminary biohazard testing at the International Space Station before the samples are brought to Earth.[71][72] DiGregorio supports the conspiracy theory of a NASA coverup regarding the discovery of microbial life by the 1976 Viking landers.[73][74] DiGregorio also supports a fringe view that several pathogens -such as common viruses- originate in space and probably caused some of the mass extinctions, and deadly pandemics.[75][76] These claims connecting terrestrial disease and extraterrestrial pathogens have been rejected by the scientific community.[75]

NASA Sample-Return Robot Challenge

The Sample-Return Robot Challenge, as part of NASA's Centennial Challenges program, offered a total $1.5 million to teams that can build fully autonomous robots that can find, retrieve, and return up to 10 different sample types within a large outdoor environment (80,000 m2).[77] The challenge started in 2012 and ended in 2016. Over 50 teams competed during the 5-year duration of the competition. A robot named Cataglyphis, developed by Team Mountaineers from West Virginia University completed the final challenge in 2016.

In popular culture

- Life (2017 film) – Fictional story set in the near future, centres around a robotic Mars sample-return space probe, which returns to the International Space Station with soil samples potentially containing evidence of extraterrestrial life. Despite taking careful precautions, the lives of the crew become endangered. The choice between personal safety and the risk of infecting Earth is an important theme in the film.

See also

- ExoMars, Aurora multi-mission flagship

- Fobos-Grunt, Russian-Chinese sample-return mission to Phobos (moon of Mars) (crashed)

- Mars 2020 rover, plans include a sample-cacher

- Mars Astrobiology Explorer-Cacher (MAX-C) (cancelled in 2011)

- Mars meteorite

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

References

- Treiman, et al. – Groundbreaking Sample Return from Mars: The Next Giant Leap in Understanding the Red Planet

- "Science Strategy – NASA Solar System Exploration". Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- Mars Sample-Return Archived 2008-05-18 at the Wayback Machine (from the NASA website. Accessed 2008-05-26.)

- http://mepag.jpl.nasa.gov/reports/iMARS_FinalReport.pdf

- NWA 6963

- Treiman, A.H.; et al. (October 2000). "The SNC meteorites are from Mars". Planetary and Space Science. 48 (12–14): 1213–1230. Bibcode:2000P&SS...48.1213T. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(00)00105-7.

- "Mars Program Gears up for Sample Return Mission".

- Space Studies Board; National Research Council (2011). "Vision and Voyages for Planetary Science in the Decade 2013–2022" (PDF). National Academies Press. p. 6‑21.

- Jones, S.M.; et al. (2008). "Ground Truth From Mars (2008) – Mars Sample Return at 6 Kilometers per Second: Practical, Low Cost, Low Risk, and Ready" (PDF). USRA. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- Return to Mars. National Geographic Magazine, August 1998 issue

- "MarsNews.com :: Mars Sample Return". 27 February 2015. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "International cooperation called key to planet exploration". 22 August 2012.

- Shirley, Donna. "Mars Exploration Program Strategy: 1995–2020" (PDF). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Groundbreaking Sample-Return from Mars: The Next Giant Leap in Understanding the Red Planet.

- http://www.livestream.com/2011lpsc/video?clipId=pla_18e48f98-4a78-4acc-ad2a-29c7a8ae326c

- Mars Planning Group Endorses Sample-Return.

- Summary of the Final Report

- Foust, Jeff (20 July 2016). "Mars 2020 rover mission to cost more than $2 billion". SpaceNews.

- Evans, Kim (13 October 2015). "NASA Eyes Sample-Return Capability for Post-2020 Mars Orbiter". Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Mattingly, Richard (March 2010). "Mission Concept Study: Planetary Science Decadal Survey – MSR Orbiter Mission (Including Mars Returned Sample Handling)" (PDF). NASA.

- Schulte, Mitch (20 December 2012). "Call for Letters of Application for Membership on the Science Definition Team for the 2020 Mars Science Rover" (PDF). NASA. NNH13ZDA003L.

- "Summary of the Final Report" (PDF). NASA / Mars Program Planning Group. 25 September 2012.

- Moskowitz, Clara (5 February 2013). "Scientists Offer Wary Support for NASA's New Mars Rover". Space.com. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- Clark, Stephen (20 April 2020). "NASA narrows design for rocket to launch samples off of Mars". SpaceFlightNow.com. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Kahn, Amina (10 February 2020). "NASA gives JPL green light for mission to bring a piece of Mars back to Earth". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- Staff (2020). "Mission to Mars – Mars Sample Return". NASA. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-22. Retrieved 2016-12-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "NASA and ESA Establish a Mars Exploration Joint Initiative". NASA. 8 July 2009.

- Christensen, Phil (April 2010). "Planetary Science Decadal Survey: MSR Lander Mission" (PDF). JPL. NASA. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- "BBC NEWS – Science/Nature – Date set for Mars sample mission". 2008-07-10.

- "Mars Sample Return: bridging robotic and human exploration". European Space Agency. 21 July 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- Rincon, Paul (26 April 2018). "Space agencies intent on mission to deliver Mars rocks to Earth". BBC News.

- Staff (26 April 2018). "Video (02:22) – Bringing Mars Back To Earth". NASA.

- Foust, Jeff (28 July 2019). "Mars sample return mission plans begin to take shape". SpaceNews.

- Cowart, Justin (13 August 2019). "NASA, ESA Officials Outline Latest Mars Sample Return Plans". The Planetary Society.

- Wall, Mike (September 27, 2012). "Bringing Pieces of Mars to Earth: How NASA Will Do It". Space.com.

- Amos, Jonathan (6 July 2018). "Fetch rover! Robot to retrieve Mars rocks". BBC News.

- "Future Planetary Exploration: New Mars Sample Return Plan". 8 December 2009.

- Strategic Technology Development for Future Mars Missions (2013–2022)Archived 2010-05-28 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) 15 September 2009

- 'Bringing back Mars life' MSNBC News, February 24, 2010 by Alan Boyle.

- Witze, Alexandra (15 May 2014). "NASA plans Mars sample-return rover". Nature. 509 (7500): 272. Bibcode:2014Natur.509..272W. doi:10.1038/509272a. PMID 24828172.

- Wadhwa, et al. – SCIM (2012)

- https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fy2021_congressional_justification.pdf – p. 469 – 10 February 2020

- "China considers more Mars probes before 2030". news.xinhuanet.com. 10 October 2012.

- Staff Writers Beijing (AFP) (10 October 2012). "China to collect samples from Mars by 2030: Xinhua". marsdaily.com.

- "China Is Racing to Make the 2020 Launch Window to Mars". Chinese Academy of Science.

- Jones, Andrew (19 December 2019). "A closer look at China's audacious Mars sample return plans". The Planetary Society.

- Plans To Land A Rover On Mars In 2020. Alexandra Lozovschi, Inquisitr. 17 January 2019.

- @EL2squirrel (12 December 2019). "China's second Mars exploration mission is a Mars Sample Retrun [sic] mission: Earth Return Orbiter will be launched in 2028, another launch for Lander&Ascender, Earth Entry Vehicle will be return in 2031. pbs.twimg.com/media/ELo1S31UYAAcbMf?format=jpg&name=large" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Counil, J.; Bonneville, R.; Rocard, F. (1 January 2002). "The french involvement in Mars sample-return program". 34th COSPAR Scientific Assembly. 34: 3166. Bibcode:2002cosp...34E3166C – via NASA ADS.

- "JAXA plans probe to bring back samples from moons of Mars". The Japan Times Online. 10 June 2015.

- Torishima, Shinya (June 19, 2015). "JAXAの「火星の衛星からのサンプル・リターン」計画とは". Mynavi News (in Japanese). Retrieved 2015-10-06.

- "火星衛星の砂回収へ JAXA「フォボス」に探査機". Nikkei (in Japanese). September 22, 2017. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- Roscosmos – Space missions Published by The Space Review (page 9) on 2010

- Dwayne A. Day, November 28, 2011 (2011-11-28). "'Red Planet blues (Monday, November 28, 2011)". The Space Review. Retrieved 2012-01-16.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kramnik, Ilya (April 18, 2012). "Russia takes a two-pronged approach to space exploration". Russia & India Report. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- Russia To Study Martian Moons Once Again. Mars Daily July 15, 2008.

- Major provisions of the Russian Federal Space Program for 2006–2015. "1 spacecraft for Mars research and delivery of Martian soil to the Earth".

- Brian Harvey; Olga Zakutnyaya (2011). Russian Space Probes: Scientific Discoveries and Future Missions. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 475. ISBN 978-1-4419-8150-9.

- "ExoMars to pave the way for soil sample return". russianspaceweb.com.

- http://mepag.nasa.gov/reports/iMARS_FinalReport.pdf Preliminary Planning for an International Mars Sample Return Mission Report of the International Mars Architecture for the Return of Samples (iMARS) Working Group June 1, 2008

- European Science Foundation – Mars Sample Return backward contamination – Strategic advice and requirements Archived 2 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine July, 2012, ISBN 978-2-918428-67-1 – see Back Planetary Protection section. (for more details of the document see abstract )

- Joshua Lederberg Parasites Face a Perpetual Dilemma Volume 65, Number 2, 1999/ American Society for Microbiology News 77.

- Assessment of Planetary Protection Requirements for Mars Sample Return Missions (Report). National Research Council. 2009.

- Mars Sample Return: Issues and Recommendations. Task Group on Issues in Sample Return. National Academies Press, Washington, DC (1997).

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-02-16. Retrieved 2013-08-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Mars Sample Return Discussions As presented on February 23, 2010

- "Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies". Archived from the original on 2013-07-08. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- "Mars Sample Return Receiving Facility" (PDF).

- Mars Sample Return Receiving Facility – A Draft Test Protocol for Detecting Possible Biohazards in Martian Samples Returned to Earth (PDF) (Report). 2002.

- Zubrin, Robert (2010). "Human Mars Exploration: The Time Is Now". Journal of Cosmology. 12: 3549–3557.

- International Committee Against Mars Sample Return.

- Barry E. DiGregorio The dilemma of Mars sample return. August 2001, Vol. 31, No. 8, pp 18–27.

- Life On Mars. Coast To Coast show. Accessed 23 August 2018.

- Local scientist has evidence of life on Mars. Mike Randall. ABC News, Buffalo. 14 February 2018.

- Joseph Patrick Byrne (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues. ABC-CLIO. pp. 454–455. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1.

- Richard Stenger Mars sample return plan carries microbial risk, group warns. CNN, November 7, 2000

- Harbaugh, Jennifer (2015-07-15). "NASA's Centennial Challenges: Sample-Return Robot Challenge". Retrieved 2016-09-16.

.jpg)

.jpg)