Italian Canadians

Italian Canadians (Italian: italo-canadesi, French: Italo-Canadiens) comprise Canadians who have full or partial Italian heritage and Italians who migrated from Italy or reside in Canada. According to the 2016 Census of Canada, 1,587,970 Canadians (4.6% of the total population) claimed full or partial Italian ancestry.[1] The census enumerates the entire Canadian population, which consists of Canadian citizens (by birth and by naturalization), landed immigrants and non-permanent residents and their families living with them in Canada.[2] Residing mainly in central urban industrial metropolitan areas, Italian Canadians are the seventh largest self-identified ethnic group in Canada behind French, English, Irish, Scottish, German and Chinese Canadians.

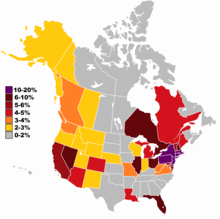

Italian Canadians and Italian Americans, % of population by state or province | |

| Total population | |

| 1,587,970 (total population) 236,635 (by birth) 1,351,335 (by ancestry) 2016 Census[1] 4.6% of Canada's population. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Greater Toronto Area, Hamilton, Niagara Region, London, Guelph, Windsor, Ottawa–Gatineau, Barrie, Sault Ste. Marie, Greater Sudbury, Thunder Bay, Greater Montreal, Greater Vancouver | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominately Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Italians, Italian Americans, Italian Argentines, Italian Brazilians, Italian Uruguayans, Italian Chileans, Italian Mexicans, Italian South Africans, Italian Australians, British Italian, Sicilian Americans, Corsican Americans |

Italian immigration to Canada started as early as the mid 19th century. A substantial influx of Italian immigration to Canada began in the early 20th century, primarily from rural southern Italy. The interwar period of World War I also instigated further migration, with immigrants primarily settling in Toronto and Montreal. After the war, new immigration laws in the 1920s limited Italian immigration. During World War II, approximately 600 to 700 Italian Canadian men were interned between 1940 and 1943 as potentially dangerous enemy aliens with alleged fascist connections. A second wave of immigration occurred after the World War II, and between the early 1950s and the mid-1960s, approximately 20,000 to 30,000 Italians immigrated to Canada each year, many of the men working in the construction industry upon settling. Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia was an influential port of Italian immigration between 1928 until it ceased operations in 1971, where 471,940 individuals came to Canada from Italy, making them the third largest ethnic group to immigrate to Canada during that time period. In the late 1960s, the Italian economy experienced a period of growth and recovery, removing one of the primary incentives for emigration. In 2010, the Government of Ontario proclaimed the month of June as Italian Heritage Month, and in 2017, the Government of Canada also declared the month of June as Italian Heritage Month across Canada.

History

The first explorer to coastal North America was the Venetian Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot), making landfall in Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland and Labrador, in 1497.[3] His voyage to Canada and other parts of the Americas was followed by his sons Sebastiano Caboto and Janus Verrazanus (Giovanni da Verrazzano). During the New France era, France also occupied parts of Northern Italy and there was a significant Italian presence in the French military forces in the colony. Notable were Alphonse de Tonty, who helped establish Detroit, and Henri de Tonti, who journeyed with La Salle in his exploration of the Mississippi River. Italians then made up a small portion of the population; at the first Canadian census in 1871, there were only 1,035 people of Italian origin that lived in Canada.[4] A number of Italians were imported to work as navvies in the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway.[5]

A substantial influx of Italian immigration to Canada began in the early 20th century when over 60,000 Italians moved to Canada between 1900 and 1913.[6] These were largely peasants from rural southern Italy and agrarian parts of the north-east (Veneto, Friuli). Approximately 40,000 Italians came to Canada during the interwar period of 1914 to 1918, predominantly from southern Italy where an economic depression and overpopulation had left many families in poverty.[6] They primarily immigrated to Toronto and Montreal.[7] In Toronto, the Italian population increased from 4,900 in 1911, to 9,000 in 1921, constituting almost two percent of Toronto's population.[8] Italians in Toronto and in Montreal soon established ethnic enclaves, especially Little Italies in Toronto and in Montreal. Smaller communities also arose in Vancouver, Hamilton, Niagara Falls, Guelph, Windsor, Sault Ste. Marie, Ottawa, Sherbrooke, Quebec City and the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean area. Many also settled in mining communities in British Columbia, Alberta, Cape Breton Island and Northern Ontario. The Northern Ontario cities of Sault Ste. Marie and Fort William were quite heavily populated by Italian immigrants. The 1905, Royal Commission appointed to Inquire into the Immigration of Italian Labourers to Montreal and alleged Fraudulent Practices of Employment Agencies exposed the abuses of immigration agents known as padroni.

This migration was largely halted after World War I, new immigration laws in the 1920s, and the Great Depression limited Italian immigration. During World War II, Italian Canadians were regarded with suspicion and faced a great deal of discrimination. As part of the War Measures Act, between 1940 and 1943, approximately 600 to 700 Italian Canadian men were arrested and sent to internment camps, such as Camp Petawawa as potentially dangerous enemy aliens with alleged fascist connections—in what was the period of Italian Canadian internment. While many Italian-Canadians had initially supported fascism and Benito Mussolini's regime for its role in enhancing Italy's presence on the world stage, most Italians in Canada did not harbour any ill will against Canada and few remained committed followers of the fascist ideology.[9][6] In 1990, former prime minister Brian Mulroney apologized for the war internment to a Toronto meeting of the National Congress of Italian Canadians.[10] In May 2009, Massimo Pacetti introduced bill C-302, an "Act to recognize the injustice that was done to persons of Italian origin through their "enemy alien" designation and internment during the Second World War, and to provide for restitution and promote education on Italian Canadian history [worth $2.5 million]", which was passed by the House of Commons on April 28, 2010;[11] Canada Post was also to issue a commemorative postage stamp commemorating the internment of Italian Canadian citizens,[12] however, Bill C-302 did not pass through the necessary stages to become law.[13]

A second wave occurred after the World War II when Italians, especially from the Lazio, Abruzzo, Friuli, Veneto, Campania, Calabria, and Sicily regions, left the war-impoverished country for opportunities in a young and growing country. Many Italians from Istria and Dalmatia also immigrated to Canada, during this period, as displaced persons (see Istrian exodus). Between the early 1950s and the mid-1960s, approximately 20,000 to 30,000 Italians immigrated to Canada each year.[6] By the 1960s, more than 15,000 Italian men worked in Toronto's construction industry, representing one third of all construction workers in the city at that time.[6] 90 percent of the Italians who immigrated to Canada after World War II remained in Canada, and decades after that period, the community still had fluency in the Italian language.[14] In the late 1960s, the Italian economy experienced a period of growth and recovery, removing one of the primary incentives for emigration.[6]

Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia was an influential port of Italian immigration between 1928 until it ceased operations in 1971, where 471,940 individuals came to Canada from Italy, making them the third largest ethnic group to immigrate to Canada during that time period.[15]

In 2010, the Government of Ontario passed Bill 103 with royal assent proclaiming the month of June as Italian Heritage Month.[16] On May 17, 2017, the Minister of Canadian Heritage Mélanie Joly passed a unanimous motion, Motion 64, in the House of Commons of Canada to recognize the month of June as Italian Heritage Month across Canada — a time to recognize, celebrate and raise awareness of the Italian community in Canada, one of the largest outside of Italy.[17]

Demographics

Ethnicity

As of the 2016 census 1,587,970 Canadian residents stated they had Italian ancestry — 4.6 percent of Canada's population, and a six percent increase from 1,488,425 population of the 2011 census.[1] From the 1,587,970, 695,420 were single ethnic origin responses, while the remaining 892,550 were multiple ethnic origin responses. The majority live in Ontario, over 900,000, (seven percent of the population), while over 300,000 live in Quebec (four percent of the population) — constituting for almost 80 percent of the national population.

| Year | Population (single and multiple ethnic origin responses) |

% of total ethnic population |

Population (single ethnic origin responses) |

Population (multiple ethnic origin responses) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1871[4] | 1,035 | 0.03% | N/A | N/A |

| 1881[4] | 1,849 | 0.04% | N/A | N/A |

| 1901[4] | 10,834 | 0.20% | N/A | N/A |

| 1911[18] | 45,411 | 0.64% | N/A | N/A |

| 1921[4] | 66,769 | 0.76% | N/A | N/A |

| 1931[4] | 98,173 | 0.95% | N/A | N/A |

| 1941[4] | 112,625 | 0.98% | N/A | N/A |

| 1951[4] | 152,245 | 1.1% | N/A | N/A |

| 1961[19] | 459,351 | 2.5% | N/A | N/A |

| 1971[4] | 730,820 | 3.4% | N/A | N/A |

| 1996[20] | 1,207,475 | 4.2% | 729,455 | 478,025 |

| 2001[21] | 1,270,370 | 4.3% | 726,275 | 544,090 |

| 2006[22] | 1,445,335 | 4.6% | 741,045 | 704,285 |

| 2011[23] | 1,488,425 | 4.5% | 700,845 | 787,580 |

| 2016[24] | 1,587,970 | 4.6% | 695,420 | 892,550 |

| Province/territory | Population (1996)[20] | % of total ethnic population (1996) | Population (2001)[21] | % of total ethnic population (2001) | Population (2006)[22] | % of total ethnic population (2006) | Population (2011)[23] | % of total ethnic population (2011) | Population (2016)[24] | % of total ethnic population (2016) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | 743,425 | 7.0% | 781,345 | 6.9% | 867,980 | 7.2% | 883,990 | 7.0% | 931,805 | 7.0% |

| Quebec | 244,740 | 3.5% | 249,205 | 3.5% | 299,655 | 4.0% | 307,810 | 4.0% | 326,700 | 4.1% |

| British Columbia | 117,895 | 3.2% | 126,420 | 3.3% | 143,160 | 3.5% | 150,660 | 3.5% | 166,090 | 3.6% |

| Alberta | 58,140 | 2.2% | 67,655 | 2.3% | 82,015 | 2.5% | 88,705 | 2.5% | 101,260 | 2.5% |

| Manitoba | 17,205 | 1.6% | 18,550 | 1.7% | 21,405 | 1.9% | 21,960 | 1.9% | 23,205 | 1.9% |

| Nova Scotia | 11,200 | 1.2% | 11,240 | 1.3% | 13,505 | 1.5% | 14,305 | 1.6% | 15,625 | 1.7% |

| Saskatchewan | 7,145 | 0.73% | 7,565 | 0.79% | 7,970 | 0.80% | 9,530 | 1.0% | 11,310 | 1.1% |

| New Brunswick | 4,645 | 0.64% | 5,610 | 0.78% | 5,900 | 0.80% | 7,195 | 1.0% | 7,460 | 1.0% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1,505 | 0.28% | 1,180 | 0.23% | 1,375 | 0.27% | 1,825 | 0.36% | 1,710 | 0.33% |

| Prince Edward Island | 515 | 0.39% | 605 | 0.45% | 1,005 | 0.75% | 955 | 0.70% | 1,200 | 0.86% |

| Yukon | 545 | 1.8% | 500 | 1.8% | 620 | 2.0% | 725 | 2.2% | 915 | 2.6% |

| Northwest Territories | 525 | 0.82% | 400 | 1.1% | 610 | 1.5% | 545 | 1.3% | 505 | 1.2% |

| Nunavut | N/A[note 1] | N/A | 95 | 0.36% | 125 | 0.40% | 215 | 0.70% | 175 | 0.49% |

| Metropolitan area | Population (2001)[26] | % of ethnic population (2001) | Population (2006)[27] | % of ethnic population (2006) | Population (2011)[28] | % of ethnic population (2011) | Population (2016)[29] | % of ethnic population (2016) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto CMA[note 2] | 429,380 | 9.2% | 466,155 | 9.2% | 475,090 | 8.6% | 484,360 | 8.3% |

| Montreal CMA | 224,460 | 6.6% | 260,345 | 7.3% | 263,565 | 7.0% | 279,795 | 7.0% |

| Greater Vancouver | 69,000 | 3.5% | 76,345 | 3.6% | 82,435 | 3.6% | 87,875 | 3.6% |

| Hamilton CMA | 67,685[note 3] | 10.3% | 72,440[note 4] | 10.6% | 75,900[note 5] | 10.7% | 79,725[note 6] | 10.8% |

| National Capital Region | 37,435 | 3.6% | 45,005 | 4.0% | 47,975 | 4.0% | 53,825 | 4.1% |

| Niagara Region | 44,645 | 12.0% | 48,850 | 12.7% | 48,530 | 12.6% | 49,345 | 12.4% |

| Greater Calgary | 29,120 | 3.1% | 33,645 | 3.1% | 36,875 | 3.1% | 42,940 | 3.1% |

| Greater Edmonton | 22,385 | 2.4% | 28,805 | 2.8% | 29,580 | 2.6% | 33,800 | 2.6% |

| Windsor | 30,680 | 10.1% | 33,725 | 10.5% | 30,880 | 9.8% | 33,175 | 10.2% |

| Oshawa CMA[note 7] | 13,990 | 4.8% | 18,225 | 5.6% | 20,265 | 5.8% | 22,870 | 6.1% |

| London | 17,290 | 4.1% | 20,380 | 4.5% | 20,210 | 4.3% | 22,625 | 4.6% |

| Greater Winnipeg | 16,105 | 2.4% | 18,580 | 2.7% | 18,405 | 2.6% | 19,435 | 2.6% |

| Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo | 11,365 | 2.8% | 13,675 | 3.1% | 14,860 | 3.2% | 18,650 | 3.6% |

| Thunder Bay | 15,395 | 12.8% | 17,290 | 14.3% | 15,575 | 13.1% | 16,610 | 14.0% |

| Sault Ste. Marie | 16,315 | 21.0% | 17,720 | 22.4% | 16,005 | 20.4% | 16,025 | 20.9% |

| Barrie | 7,450 | 5.1% | 10,330 | 5.9% | 11,415 | 6.2% | 14,460 | 7.4% |

| Guelph | 11,135 | 9.6% | 12,110 | 9.6% | 12,915 | 9.3% | 14,430 | 9.6% |

| Greater Sudbury | 12,030 | 7.8% | 13,415 | 8.6% | 13,115 | 8.3% | 13,500 | 8.3% |

| Victoria | 7,975 | 2.6% | 9,450 | 2.9% | 10,535 | 3.1% | 11,665 | 3.3% |

Language and immigration

As of 2016, of the 1,587,970 population, 236,635 are Italian born immigrants,[30] with 375,645 claiming Italian as their mother tongue.[31]

| Year | Population | % of non-official language mother tongue speakers in Canada |

% of all language mother tongue speakers in Canada |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991[32] | 510,990 | 12.7% | 1.9% |

| 1996[33] | 484,500 | 10.5% | 1.7% |

| 2001[34] | 469,485 | 9.0% | 1.6% |

| 2006[35] | 455,040 | 7.4% | 1.5% |

| 2011[36] | 407,485 | 6.2% | 1.2% |

| 2016[37] | 375,645 | 5.1% | 1.1% |

| Year | Population | % of immigrants in Canada |

% of Canadian population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986[38] | 366,820 | 9.4% | 1.5% |

| 1991[38] | 351,615 | 8.1% | 1.3% |

| 1996[38] | 332,110 | 6.7% | 1.2% |

| 2001[39] | 315,455 | 5.8% | 1.1% |

| 2006[40] | 296,850 | 4.8% | 0.94% |

| 2011[41] | 260,250 | 3.6% | 0.78% |

| 2016[30] | 236,635 | 3.1% | 0.67% |

Italian Canadian culture

Radio and television

Son to Italian immigrants, Johnny Lombardi was born in The Ward in 1915, and went on to found one of the first multilingual radio stations in Canada, CHIN in 1966, in Palmerston–Little Italy.[42][43]

Dan Iannuzzi founded the first multicultural television station in Canada (CFMT-TV), which began operations in Toronto in 1979. Now owned by Rogers Communications, the service has spun off into two multicultural television services in southern Ontario: OMNI-1 and OMNI-2.[44]

In 1997, a reform of the city's multicultural television station (CJNT) saw a drastic decline in the quality of all programming and major cuts to airtime. At one time, CJNT was on air for less than twelve hours a day. The CanWest Global company later purchased the station and has since improved programming. Nevertheless, there is now little Italian programming shown.

Telelatino (TLN) is widely available through cable distribution. Though offering programmes in both Spanish and Italian, most of TLN's revenue is derived from the latter.

RAI controversy

In Canada, Rai Italia's programming was originally seen on Telelatino, a Canadian licensed channel launched in 1984 and currently majority owned by Corus together with three prominent Italian-Canadians. TLN was launched over a decade before a RAI international TV channel ever existed. TLN had provided a level of availability and variety of Italian domestic and foreign programming to Canadians that was unsurpassed anywhere outside Italy. However, in 2003, RAI pulled the Rai International programming from Telelatino and, with the help of Rogers Communications (which itself owns several multicultural stations in Toronto under the Omni Television system), petitioned the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) to allow Rai Italia to be broadcast in Canada.[45] Although the Italian community in Montreal was in favour of admitting Rai International into the Canadian media marketplace, the Italian community in Toronto was divided, since some believed that it was a ploy by the then Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi to gain influence over Canadian Italian-language media. This theory may have been advanced by Telelatino's primary carriage of programming from Berlusconi-controlled Mediaset after RAI's Canadian launch.

Originally, the CRTC denied RAI's application, on the grounds that RAI had improperly denied supply of programming to TLN's Canadian viewers and that RAI's attempt to enter Canada on an unrestricted basis without any Canadian programming and financial obligations would be unfair competition. However, some Italian-Canadians could watch Rai Italia through grey-market satellite TV viewing cards that allowed them to watch US satellite television. Eventually, in 2005, the CRTC allowed Rai Italia to broadcast in Canada after a review of its policy on third-language foreign language TV services.

Newspapers and magazines

The first Italian-language newspaper in Canada was Il Lavoratore, an anti-Fascist publication which was founded in Toronto in 1936 and active for two years. Then came La Voce degli Italo Canadesi, founded in Toronto (1938-1940) and Il Cittadino Canadese, founded in Montreal in 1941, followed by La Vittoria of Toronto, in 1942-1943. After WWII came Il Corriere Italiano, founded by Alfredo Gagliardi in Montreal in the early 1950s. Corriere Canadese, founded by Dan Iannuzzi in 1954, is Canada's only Italian-language daily today and is published in Toronto; its weekend (English-language) edition is published as Tandem.

Other newspapers include Il Marco Polo (Vancouver), founded in 1974, Insieme (Montreal), Lo Specchio (Toronto), L'Ora di Ottawa (Ottawa) and Il Postino (Ottawa). Il Postino was established in 2000, by a young group of local Ottawa Italian Canadians to convey the history of the Italian community in Ottawa.[46] Insieme was founded by the Italian Catholic parishes of Montreal but has since been put under private ownership. It nevertheless retains an emphasis on religious articles.

Eyetalian magazine was launched in 1993 as a challenging, independent magazine of Italian-Canadian culture. It encountered commercial difficulty, and leaned towards a general lifestyle magazine format before concluding publication later in the 1990s. Italo of Montreal is published sporadically and is written in Italian, with some articles in French and English, dealing with current affairs and community news. La Comunità, while an older publication, was taken over by the youth wing of the National Congress of Italian Canadians (Québec chapter) in the late 1990s. It experimented with different formats but was later cancelled due to lack of funding. In the 1970s the trilingual arts magazine Vice Versa flourished in Montreal. In, 2003 Domenic Cusmano founded Accenti, the magazine which focused on culture and Italian-Canadian authors.

Literature

Italian Canadian literature emerged in the 1970s as young Italian immigrants began to complete university degrees across Canada. This creative writing exists in English, French, or Italian. Some writers like Antonio D'Alfonso, Marco Micone, Alexandre Amprimoz and Filippo Salvatore are bilingual and publish in two languages. The older generation of authors like Maria Ardizzi, Romano Perticarini, Giovanni Costa and Tonino Caticchio publish in Italian or in bilingual volumes. In English the most notable names are novelists Frank G. Paci, Nino Ricci, Caterina Edwards, Michael Mirolla and Darlene Madott. Poets who write in English include Mary di Michele, Pier Giorgio DiCicco and Gianna Patriarca. In 1986 these authors established the Association of Italian-Canadian Writers,[47] and by 2001 there were over 100 active writers publishing books of poetry, fiction, drama and anthologies. With the 1985 publication of Contrasts: Comparative Essays on Italian-Canadian Writing by Joseph Pivato, the academic study of this literature started, leading to the exploration of other ethnic minority writing in Canada and inspiring other scholars such as Licia Canton, Pasquale Verdicchio and George Elliott Clarke. The important collections of literary works are: The Anthology of Italian-Canadian Writing (1998) edited by Joseph Pivato and Pillars of Lace: The Anthology of Italian-Canadian Women Writers (1998) edited by Marisa De Franceschi. See also Writing Cultural Difference: Italian-Canadian Creative and Critical Works (2015) editors Giulia De Gasperi, Maria Cristina Seccia, Licia Canton and Michael Mirolla.

Education

On October 25, 2012, the Government of Canada announced its support of a project highlighting Italian-Canadian contribution to Canada. Funding aimed at raising awareness of the contributions of Canadians of Italian heritage in the development and settlement of Canada was announced by Julian Fantino, Minister of International Cooperation and Member of Parliament for Vaughan, on behalf of Citizenship and Immigration Canada.[48]

Citizenship and Immigration Canada is providing $248,397 in funding under the Inter-Action Program to the Toronto district of the National Council of Italian Canadians (NCIC) to develop a curriculum intended for both primary and secondary level classes. The project is entitled "Italian Heritage in Canada Curriculum."[48]

"The Inter-Action program aims to create opportunities for different cultural and faith communities to build bridges and promote intercultural understanding," said Minister Fantino. "This project will help promote a greater awareness of the many contributions of the Italian Canadian community to the building of Canada."[48]

The curriculum will start with the Discovery of North America on June 24, 1497, and then turn to the various waves of immigrants that came to Canada from the 1800s to the present time. It will showcase Italian immigration to urban and rural areas across Canada and their contributions to the settlement of the west, then the building of railways, cities and infrastructure. The curriculum will recount the work of earlier generations of Italians, their plight during World War II when many were interned, and the contributions of more recent generations of Canadians of Italian heritage. It will also explore the wartime internment experiences of other cultural communities as well as their contributions to the building of Canada.[48]

Notable Italian Canadians

Italian districts in Canada

Alberta

- Crowsnest Pass, Alberta

- Little Italy, Edmonton

Greater Montreal area

Hamilton

Greater Toronto Area

- Little Italy, Toronto

- Palmerston–Little Italy, Toronto

- Corso Italia – St. Clair Avenue West

- Corso Italia-Davenport, Toronto

- Maple Leaf, Toronto

- Downsview, Toronto

- Woodbridge, Vaughan

- Nobleton, King

- Bolton, Caledon

Windsor, Ontario

British Columbia

- Burnaby, British Columbia

- Little Italy, Vancouver

- Trail, British Columbia

Manitoba

See also

Notes

- Before it separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the Nunavut Act.[25]

- See Italian Canadians in the Greater Toronto Area for more detailed information. Unlike the Greater Toronto Area, the Toronto CMA does not include the Halton municipality of Burlington, and some Durham municipalities, those being Scugog and Brock, as well as those within the Oshawa CMA (Oshawa, Whitby, and Clarington). It does, however, include some municipalities outside the Greater Toronto Area, those being the Dufferin County municipalities of Mono and Orangeville, and the Simcoe County municipalities of Bradford West Gwillimbury and New Tecumseth. The Greater Toronto Area, comprises the whole of the Regional Municipality of York, Regional Municipality of Durham, Regional Municipality of Halton, Regional Municipality of Peel and the City of Toronto.

- Includes Hamilton (56,265, 11.6% of total population), Burlington (9,520, 6.4% of total population) and Grimsby (1,905, 9.1% of total population)

- Includes Hamilton (58,800, 11.8% of total population), Burlington (11,430, 7.0% of total population) and Grimsby (2,215, 9.4% of total population)

- Includes Hamilton (60,535, 11.9% of total population), Burlington (12,755, 7.4% of total population) and Grimsby (2,610, 10.4% of total population)

- Includes Hamilton (62,335, 11.8% of total population), Burlington (14,235, 7.9% of total population) and Grimsby (3,155 11.8% of total population)

- Includes the municipalities of Oshawa, Whitby, and Clarington. See Italian Canadians in the Greater Toronto Area for more detailed information.

References

- Statistics Canada (2017-10-25). "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables". Archived from the original on 2017-10-27. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- "Census of Population". Statistics Canada. February 2019. Archived from the original on 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- Derek Croxton (2007). "The Cabot Dilemma: John Cabot's 1497 Voyage & the Limits of Historiography". University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Elspeth Cameron (2004). Multiculturalism and Immigration in Canada: An Introductory Reader. Canadian Scholars' Press.

- "Italian Canadians". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on July 23, 2019. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- "History - Pier 21". www.pier21.ca. Archived from the original on 2017-07-21. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- Johanne Sloan (2007). Urban Enigmas: Montreal, Toronto, and the Problem of Comparing Cities.

- Sturino, Franc (1990). Forging the chain: a case study of Italian migration to North America, 2000-1930. Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario. p. 168. ISBN 0-919045-45-6.

- "Italian Canadians as Enemy Aliens: Memories of World War II". www.italiancanadianww2.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-06-01. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- "Italians seek new apology from Canada for wartime internments". The Globe and Mail. 30 April 2010. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Third Session, Fortieth Parliament, House of Commons, Bill C–302 Retrieved January 2, 2011. (pdf file)

- "Apology to interned Italian-Canadians questioned". Archived from the original on 2018-04-12. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- "Redress and Apology". www.italiancanadianww2.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-06-02. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- Stanger-Ross, p. 30.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-16. Retrieved 2017-07-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Bill 103, Italian Heritage Month Act, 2010". ola.org. Archived from the original on 2019-06-02. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- "Statement by Minister Joly on Italian Heritage Month". canada.ca. June 1, 2017. Archived from the original on June 2, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- "Canada" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research. 1931. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-11-03. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. "Distribution of the population, by ethnic group, census years 1941, 1951 and 1961". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2013-07-01.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (1998-02-17). "1996 Census of Canada: Data tables – Population by Ethnic Origin (188) and Sex (3), Showing Single and Multiple Responses (3), for Canada, Provinces, Territories and Census Metropolitan Areas, 1996 Census (20% Sample Data)". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-08-12. Retrieved 2019-09-20.

- contenu, English name of the content author / Nom en anglais de l'auteur du. "English title / Titre en anglais". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2019-09-20.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2008-04-02). "Statistics Canada: Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada Highlight Tables, 2006 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-08-12. Retrieved 2019-09-20.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2013-05-08). "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables – Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-01-10. Retrieved 2019-09-20.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2017-10-25). "Ethnic Origin (279), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age (12) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 Census - 25% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-10-02. Retrieved 2019-09-21.

- "Nunavut Act". Justice Canada. 1993. Archived from the original on July 24, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- "Census Metropolitan Area". Statistics Canada.

- "Census Metropolitan Area". Statistics Canada.

- "Census Metropolitan Area". Statistics Canada.

- "Census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 2017-12-07. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- "Data tables, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 2020-02-18. Retrieved 2020-01-04.

- "Data tables, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- Topic-based tabulations|Detailed Mother Tongue (103), Knowledge of Official Languages, 1991 Census of Canada

- Topic-based tabulations|Detailed Mother Tongue (103), Knowledge of Official Languages, 1996 Census of Canada

- Topic-based tabulations|Detailed Mother Tongue (103), Knowledge of Official Languages, 2001 Census of Canada

- Topic-based tabulations|Detailed Mother Tongue (103), Knowledge of Official Languages, 2006 Census of Canada Archived July 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Census Profile – Province/Territory, Note 20". Archived from the original on 2016-05-16. Retrieved 2020-01-04.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Canada". Statistics Canada. August 2, 2017. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- Immigrant Population by Selected Places of Birth (84) and Sex (3), for Canada, Provinces, Territories and Census Metropolitan Areas, 1986-1996 Censuses (20% Sample Data), 1996 Census of Canada

- Place of birth for the immigrant population by period of immigration, 2006 counts and percentage distribution, for Canada, provinces and territories - 20% sample data, 2001 Census of Canada

- Topic-based tabulations|Place of birth for the immigrant population by period of immigration, 2006 counts and percentage distribution, for Canada, provinces and territories - 20% sample data, 2006 Census of Canada Archived July 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Citizenship (5), Place of Birth (236), Immigrant Status and Period of Immigration (11), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". Archived from the original on 2017-06-15. Retrieved 2020-01-06.

- "Media legend Johnny Lombardi dies at 86". CTV News. 19 March 2002. Archived from the original on 4 December 2005. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

Prime Minister Jean Chretien praised Lombardi's accomplishments upon hearing of his death. "I think he's done a lot to establish multiculturalism in Toronto and he will be missed by a lot of people," Chretien said.

- User, Super. "Johnny Lombardi". www.chinradio.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-02. Retrieved 2020-01-07.

- "Corriere.com - Corriere Canadese Online". 2011-10-08. Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20040229000238/http://www.international.rai.it/canada/continuazioni_stampa/20040109_c.shtml

- "Il Postino". www.ilpostinocanada.com. Archived from the original on 2019-09-06. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- "aicw". www.aicw.ca. Archived from the original on 2015-02-19. Retrieved 2015-02-25.

- "The Government of Canada announces support to project highlighting Canadian-Italian contribution to Canada". canada.ca. 25 October 2012. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

Further reading

- Colantonio, Frank (1997). From the Ground up: an Italian Immigrant's Story. Toronto, Ont.: Between the Lines. 174 p., ill. with b&w photos.

- Fanella, Antonella (1999), With heart and soul: Calgary's Italian community, University of Calgary Press, ISBN 1-55238-020-3

- Marisa De, Franceschi (1998), Pillars of lace: the anthology of Italian-Canadian women writers, Guernica, ISBN 1-55071-055-9

- Iacovetta, Franca (1993), Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto, McGill-Queen's University Press, ISBN 0-7735-1145-8

- Pivato, Joseph (1998), The anthology of Italian-Canadian writing, Guernica, ISBN 1-55071-069-9

- Pivato, Joseph (1994) Echo: Essay on Other Literatures. Toronto: Guernica Editions.

- Harney, Nicholas De Maria (1998), Eh, paesan!: being Italian in Toronto, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-8020-4259-7

- Harney, Nicholas DeMaria. "Ethnicity, Social Organization, and Urban Space: A Comparison of Italians in Toronto and Montreal" (Chapter 6). In: Sloan, Joanne (editor). Urban Enigmas: Montreal, Toronto, and the Problem of Comparing Cities (Volume 2 of Culture of Cities). McGill-Queen's Press (MQUP), January 1, 2007. ISBN 0773577076, 9780773577077. Start p. 178.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canadians of Italian descent. |

- Italian Canadians as Enemy Aliens: Memories of World War II

- The Canadian Museum of Civilization - Italian Canadian Heritage

- Canadian Italians at The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Bibliography

- A History of Italian-Canadian Writing

- History of Ours: History of Italo-Canadian People in Brantford

- Italian Canadians in Italy

- Multicultural Canada website includes digitized books, newspapers and documents, as well as Italian Canadian women oral history and photographic education.