Cape Breton Island

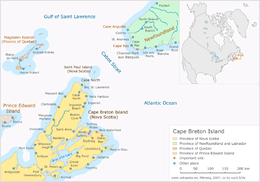

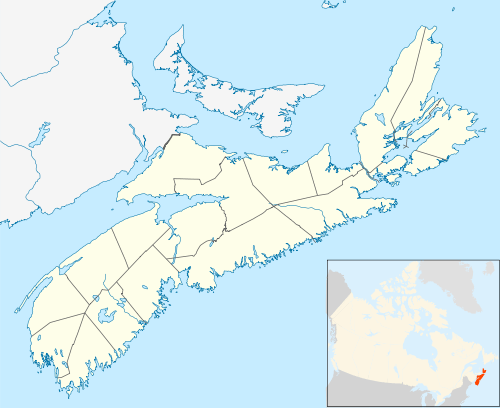

Cape Breton Island (French: île du Cap-Breton—formerly Île Royale; Scottish Gaelic: Ceap Breatainn or Eilean Cheap Breatainn; Mi'kmaq: Unamaꞌkik; or simply Cape Breton) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.[4]

| |

|---|---|

Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada | |

Cape Breton Cape Breton Island (Nova Scotia, Canada) | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Nova Scotia, Canada |

| Coordinates | 46°10′N 60°45′W |

| Area | 10,311 km2 (3,981 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 77th |

| Highest elevation | 535 m (1,755 ft) |

| Highest point | White Hill |

| Administration | |

Canada | |

| Province | Nova Scotia |

| Largest settlement | Cape Breton Regional Municipality (pop. 97,398[1]) |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Cape Bretoner[2] |

| Population | 132,010[3] (2016) |

| Pop. density | 12.7/km2 (32.9/sq mi) |

The 10,311 km2 (3,981 sq mi) island accounts for 18.7% of Nova Scotia's total area. Although the island is physically separated from the Nova Scotia peninsula by the Strait of Canso, the 1,385 m (4,544 ft) long rock-fill Canso Causeway connects it to mainland Nova Scotia. The island is east-northeast of the mainland with its northern and western coasts fronting on the Gulf of Saint Lawrence; its western coast also forms the eastern limits of the Northumberland Strait. The eastern and southern coasts front the Atlantic Ocean; its eastern coast also forms the western limits of the Cabot Strait. Its landmass slopes upward from south to north, culminating in the highlands of its northern cape. One of the world's larger salt water lakes, Bras d'Or ("Arm of Gold" in French), dominates the island's centre.

The island is divided into four of Nova Scotia's eighteen counties: Cape Breton, Inverness, Richmond, and Victoria. Their total population at the 2016 census numbered 132,010 Cape Bretoners; this is approximately 15% of the provincial population.[3] Cape Breton Island has experienced a decline in population of approximately 2.9% since the 2011 census. Approximately 75% of the island's population is in the Cape Breton Regional Municipality (CBRM) which includes all of Cape Breton County and is often referred to as Industrial Cape Breton, given the history of coal mining and steel manufacturing in this area, which was Nova Scotia's industrial heartland throughout the 20th century.

The island has five reserves of the Mi'kmaq Nation: Eskasoni, Membertou, Wagmatcook, Waycobah, and Potlotek/Chapel Island. Eskasoni is the largest in both population and land area.

Toponymy

Its name may derive from Capbreton near Bayonne, or more probably from Cape and the word Breton, the French demonym for Bretagne, the French historical region.[4] William Francis Ganong, however, rejects a French origin for the name and offers instead that the earliest form of the name appeared on Portuguese maps as "bertomes", and, he argues, "that word meant at the time the English and not the French Bretons, and referred to the region which John Cabot and his Bristol Englishmen discovered on the voyage of 1497...therefore our Cape Breton would mean 'Cape of the English'."[5]

History

Cape Breton Island's first residents were likely Archaic maritime natives, ancestors of the Mi'kmaq. These peoples and their progeny inhabited the island (known as Unama'ki) for several thousand years and continue to live there to this day. Their traditional lifestyle centred around hunting and fishing because of the unfavourable agricultural conditions of their maritime home. This ocean-centric lifestyle did, however, make them among the first indigenous peoples to discover European explorers and sailors fishing in the St Lawrence Estuary. John Cabot reportedly visited the island in 1497.[4] However, European histories and maps of the period are of too poor quality to be sure whether Cabot first visited Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island. This discovery is commemorated by Cape Breton's Cabot Trail, and by the Cabot's Landing Historic Site & Provincial Park, near the village of Dingwall.

The local Mi'kmaq peoples began trading with European fishermen when the fishermen began landing in their territories as early as the 1520s. In about 1521–22, the Portuguese under João Álvares Fagundes established a fishing colony on the island. As many as two hundred settlers lived in a village, the name of which is not known, located according to some historians at what is now Ingonish on the island's northeastern peninsula. These fishermen traded with the local population but did not maintain a permanent settlement. This Portuguese colony's fate is unknown, but it is mentioned as late as 1570.[6]

During the Anglo-French War of 1627 to 1629, under Charles I, the Kirkes took Quebec City; Sir James Stewart[4] of Killeith, Lord Ochiltree planted a colony on Unama'ki at Baleine, Nova Scotia; and Alexander's son, William Alexander, 1st Earl of Stirling, established the first incarnation of "New Scotland" at Port Royal. These claims, and larger European ideals of native conquest were the first time the island was incorporated as European territory, though it would be several decades later that treaties would actually be signed (no copies of these treaties exist).

These Scottish triumphs, which left Cape Sable as the only major French holding in North America, did not last.[7] Charles I's haste to make peace with France on the terms most beneficial to him meant the new North American gains would be bargained away in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1632),[8] which established which European power had claim over the territories, but did not in fact establish that Europeans had any claim to begin with.

The French quickly defeated the Scots at Baleine, and established the first European settlements on Île Royale: present day Englishtown (1629) and St. Peter's (1630). These settlements lasted only one generation, until Nicolas Denys left in 1659. The island did not have any European settlers for another fifty years before those communities along with Louisbourg were re-established in 1713, after which point European settlement was permanently established on the island.

Île Royale

.svg.png)

Known as "Île Royale" ("Royal Island") to the French, the island also saw active settlement by France. After the French ceded their claims to Newfoundland and the Acadian mainland to the British by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, the French relocated the population of Plaisance, Newfoundland, to Île Royale and the French garrison was established in the central eastern part at Sainte Anne. As the harbour at Sainte Anne experienced icing problems, it was decided to build a much larger fortification at Louisbourg to improve defences at the entrance to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and to defend France's fishing fleet on the Grand Banks.[9] The French also built the Louisbourg Lighthouse in 1734, the first lighthouse in Canada and one of the first in North America. In addition to Cape Breton Island, the French colony of Île Royale also included Île Saint-Jean, today called Prince Edward Island, and Les Îles-de-la-Madeleine.

French and Indian War

Louisbourg itself was one of the most important commercial and military centres in New France. Louisbourg was captured by New Englanders[4] with British naval assistance in 1745[10] and by British forces in 1758. The French population of Île Royale was deported to France after each siege. While French settlers returned to their homes in Île Royale after the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle was signed in 1748,[10] the fortress was demolished after the second siege. Île Royale remained formally part of New France until it was ceded to Great Britain by the Treaty of Paris in 1763. It was then merged with the adjacent, British colony of Nova Scotia (present day peninsular Nova Scotia and New Brunswick). Acadians who had been expelled from Nova Scotia and Île Royale were permitted to settle in Cape Breton beginning in 1764,[10] and established communities in north-western Cape Breton, near Cheticamp, and southern Cape Breton, on and near Isle Madame.

Some of the first British-sanctioned settlers on the island following the Seven Years' War were Irish, although upon settlement they merged with local French communities to form a culture rich in music and tradition. From 1763 to 1784, the island was administratively part of the colony of Nova Scotia[4] and was governed from Halifax.

The first permanently settled Scottish community on Cape Breton Island was Judique, settled in 1775 by Michael Mor MacDonald. He spent his first winter using his upside-down boat for shelter, which is reflected in the architecture of the village's Community Centre. He composed a song about the area called "O 's àlainn an t-àite", or "O, Fair is the Place."

American Revolution

.png)

During the American Revolution, on 1 November 1776, John Paul Jones – the father of the American Navy – set sail in command of Alfred to free hundreds of American prisoners working in the area's coal mines. Although winter conditions prevented the freeing of the prisoners, the mission did result in the capture of Mellish, a vessel carrying a vital supply of winter clothing intended for John Burgoyne's troops in Canada.

Major Timothy Hierlihy and his regiment on board HMS Hope worked in and protected from privateer attacks on the coal mines at Sydney Cape Breton.[14] Sydney Cape Breton provided a vital supply of coal for Halifax throughout the war. The British began developing the mining site at Sydney Mines in 1777. On 14 May 1778, Major Hierlihy arrived at Cape Breton. While there, Hierlihy reported that he "beat off many piratical attacks, killed some and took other prisoners."[15][16]

A few years into the war there was also a naval engagement between French ships and a British convoy off Sydney, Nova Scotia, near Spanish River (1781), Cape Breton.[17] French ships (fighting with the Americans) were re-coaling and defeated a British convoy. Six French sailors were killed and 17 British, with many more wounded.

Colony of Cape Breton

.svg.png)

In 1784, Britain split the colony of Nova Scotia into three separate colonies: New Brunswick, Cape Breton Island, and present-day peninsular Nova Scotia, in addition to the adjacent colonies of St. John's Island (renamed Prince Edward Island in 1798) and Newfoundland. The colony of Cape Breton Island had its capital at Sydney on its namesake harbour fronting on Spanish Bay and the Cabot Strait. Its first Lieutenant-Governor was Joseph Frederick Wallet DesBarres (1784–1787) and his successor was William Macarmick (1787).

A number of United Empire Loyalists emigrated to the Canadian colonies, including Cape Breton. David Mathews, the former Mayor of New York City during the American Revolution, emigrated with his family to Cape Breton in 1783. He succeeded Macarmick as head of the colony and served from 1795 to 1798.[18]

From 1799 to 1807, the military commandant was John Despard,[19] brother of Edward.[20]

An order forbidding the granting of land in Cape Breton, issued in 1763, was removed in 1784. The mineral rights to the island were given over to the Duke of York by an order-in-council. The British government had intended that the Crown take over the operation of the mines when Cape Breton was made a colony, but this was never done, probably because of the rehabilitation cost of the mines. The mines were in a neglected state, caused by careless operations dating back at least to the time of the final fall of Louisbourg in 1758.

Large-scale shipbuilding began in the 1790s, beginning with schooners for local trade moving in the 1820s to larger brigs and brigantines, mostly built for British shipowners. Shipbuilding peaked in the 1850s, marked in 1851 by the full-rigged ship Lord Clarendon, the largest wooden ship ever built in Cape Breton.

Merger with Nova Scotia

In 1820, the colony of Cape Breton Island was merged for the second time with Nova Scotia. This development is one of the factors which led to large-scale industrial development in the Sydney Coal Field of eastern Cape Breton County. By the late 19th century, as a result of the faster shipping, expanding fishery and industrialization of the island, exchanges of people between the island of Newfoundland and Cape Breton increased, beginning a cultural exchange that continues to this day.

The 1920s were some of the most violent times in Cape Breton. They were marked by several severe labour disputes. The famous murder of William Davis by strike breakers, and the seizing of the New Waterford power plant by striking miners led to a major union sentiment that persists to this day in some circles. William Davis Miners' Memorial Day is celebrated in coal mining towns to commemorate the deaths of miners at the hands of the coal companies.

20th century

The turn of the 20th century saw Cape Breton Island at the forefront of scientific achievement with the now-famous activities launched by inventors Alexander Graham Bell and Guglielmo Marconi.

Following his successful invention of the telephone and being relatively wealthy, Bell acquired land near Baddeck in 1885, largely due to surroundings reminiscent of his early years in Scotland. He established a summer estate complete with research laboratories, working with deaf people—including Helen Keller—and continued to invent. Baddeck would be the site of his experiments with hydrofoil technologies as well as the Aerial Experiment Association, financed by his wife, which saw the first powered flight in Canada when the AEA Silver Dart took off from the ice-covered waters of Bras d'Or Lake. Bell also built the forerunner to the iron lung and experimented with breeding sheep.

Marconi's contributions to Cape Breton Island were also quite significant, as he used the island's geography to his advantage in transmitting the first North American trans-Atlantic radio message from a station constructed at Table Head in Glace Bay to a receiving station at Poldhu in Cornwall, England. Marconi's pioneering work in Cape Breton marked the beginning of modern radio technology. Marconi's station at Marconi Towers, on the outskirts of Glace Bay, became the chief communication centre for the Royal Canadian Navy in World War I through to the early years of World War II.

Promotions for tourism beginning in the 1950s recognized the importance of the Scottish culture to the province, and the provincial government started encouraging the use of Gaelic once again. The establishment of funding for the Gaelic College of Celtic Arts and Crafts and formal Gaelic language courses in public schools are intended to address the near-loss of this culture to English assimilation.

In the 1960s, the Fortress of Louisbourg was partially reconstructed by Parks Canada. Since 2009, this National Historic Site of Canada has attracted an average of 90 000 visitors per year.[21]

Gaelic speakers

Gaelic speakers in Cape Breton, as elsewhere in Nova Scotia, furnished a large proportion of the local population from the eighteenth century on. They brought with them a common culture of poetry, traditional songs and tales, music and dance, and used this to develop distinctive local traditions.[22]

Most Gaelic settlement in Nova Scotia happened between 1770 and 1840, with probably over 50,000 Gaelic speakers emigrating from the Scottish Highlands and the Hebrides to Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. Such emigration was facilitated by changes in Gaelic society and the economy, with sharp increases in rents, confiscation of land and disruption of local customs and rights. In Nova Scotia, poetry and song in Gaelic flourished. George Emmerson argues that an "ancient and rich" tradition of storytelling, song, and Gaelic poetry emerged during the eighteenth century and was transplanted from the Highlands of Scotland to Nova Scotia, where the language similarly took root there.[23] The majority of those settling in Nova Scotia from the end of the eighteenth century through to middle of the next were from the Scottish Highlands, rather than the Lowlands, making the Highland tradition's impact more profound on the region.[24] Gaelic settlement in Cape Breton began in earnest in the early nineteenth century.[25]

The Gaelic language became dominant from Colchester County in the west of Nova Scotia into Cape Breton County in the east. It was reinforced in Cape Breton in the first half of the 19th century with an influx of Highland Scots numbering approximately 50,000 as a result of the Highland Clearances.[26][27]

Gaelic speakers, however, tended to be poor; they were largely illiterate and had little access to education. This situation still obtained in the early twentieth century. In 1921 Gaelic was approved as an optional subject in the curriculum of Nova Scotia, but few teachers could be found and children were discouraged from using the language in schools. By 1931 the number of Gaelic speakers in Nova Scotia had fallen to approximately 25,000, mostly in discrete pockets. In Cape Breton it was still a majority language, but the proportion was falling. Children were no longer being raised with Gaelic.[28]

From 1939 on, attempts were made to strengthen its position in the public school system in Nova Scotia, but funding, official commitment and the availability of teachers continued to be a problem. By the 1950s the number of speakers was less than 7,000. The advent of multiculturalism in Canada in the 1960s meant that new educational opportunities became available, with a gradual strengthening of the language at secondary and tertiary level. At present several schools in Cape Breton offer Gaelic Studies and Gaelic language programs, and the language is taught at University College of Cape Breton.[29]

The 2016 Canadian Census shows that there are only 40 reported speakers of Gaelic as a mother tongue in Cape Breton.[30] On the other hand, there are families and individuals who have recommenced intergenerational transmission. They include fluent speakers from Gaelic-speaking areas of Scotland and speakers who became fluent in Nova Scotia and who in some cases studied in Scotland. Other revitalization activities include adult education, community cultural events and publishing.[31]

Environment

Geography

The island measures 10,311 square kilometres (3,981 sq mi) in area, making it the 77th largest island in the world and Canada's 18th largest island. Cape Breton Island is composed mainly of rocky shores, rolling farmland, glacial valleys, barren headlands, mountains, woods and plateaus. Geological evidence suggests at least part of the island was joined with present-day Scotland and Norway, now separated by millions of years of plate tectonics.

Cape Breton Island's northern portion is dominated by the Cape Breton Highlands, commonly shortened to simply the "Highlands", which are an extension of the Appalachian mountain chain. The Highlands comprise the northern portions of Inverness and Victoria counties. In 1936, the federal government established the Cape Breton Highlands National Park covering 949 km2 (366 sq mi) across the northern third of the Highlands. The Cabot Trail scenic highway also encircles the plateau's coastal perimeter.

Cape Breton Island's hydrological features include the Bras d'Or Lake system, a salt-water fjord at the heart of the island, and freshwater features including Lake Ainslie, the Margaree River system, and the Mira River. Innumerable smaller rivers and streams drain into the Bras d'Or Lake estuary and on to the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Atlantic coasts.

Cape Breton Island is joined to the mainland by the Canso Causeway, which was completed in 1955, enabling direct road and rail traffic to and from the island, but requiring marine traffic to pass through the Canso Canal at the eastern end of the causeway.

Cape Breton Island is divided into four counties: Cape Breton, Inverness, Richmond, and Victoria.

The climate is one of mild, often pleasantly warm summers and cold winters, although the proximity to the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf Stream moderates the extreme winter cold found on the mainland, especially on the east side that faces the Atlantic. Precipitation is abundant year round, with annual totals up to 60 inches on the eastern side facing the Atlantic storms. Considerable snowfall occurs in winter, especially in the highlands.

Wildlife

Demographics

The island's residents can be grouped into five main cultures: Scottish, Mi'kmaq, Acadian, Irish, English, with respective languages Scottish Gaelic, Mi'kmaq, French, and English. English is now the primary language, including a locally distinctive Cape Breton accent, while Mi'kmaq, Scottish Gaelic and Acadian French are still spoken in some communities.

Later migrations of Black Loyalists, Italians, and Eastern Europeans mostly settled in the island's eastern part around the industrial Cape Breton region. Cape Breton Island's population has been in decline two decades with an increasing exodus in recent years due to economic conditions.

According to the Census of Canada, the population of Cape Breton [Economic region] in 2016 / 2011 / 2006 / 1996 was 132,010 / 135,974 / 142,298 / 158,260.

Religious groups

Statistics Canada in 2001 reported a "religion" total of 145,525 for Cape Breton, including 5,245 with "no religious affiliation."[32][33] Major categories included:

- Roman Catholic : 96,260 (includes Eastern Catholic, Polish National Catholic Church, Old Catholic)

- Protestant: 42,390

- Christian, not included elsewhere: 580

- Orthodox: 395

- Jewish: 250

- Muslim: 145

Economy

Much of the recent economic history of Cape Breton Island can be tied to the coal industry.

The island has two major coal deposits:

- the Sydney Coal Field in the southeastern part of the island along the Atlantic Ocean drove the Industrial Cape Breton economy throughout the 19th and 20th centuries—until after World War II, its industries were the largest private employers in Canada.

- the Inverness Coal Field in the western part of the island along the Gulf of St. Lawrence is significantly smaller but hosted several mines.

Sydney has traditionally been the main port, with facilities in a large, sheltered, natural harbour. It is the island's largest commercial centre and home to the Cape Breton Post daily newspaper, as well as one television station, CJCB-TV (CTV),[Note 1] and several radio stations. The Marine Atlantic terminal at North Sydney is the terminal for large ferries traveling to Channel-Port aux Basques and seasonally to Argentia, both on the island of Newfoundland.

Point Edward on the west side of Sydney Harbour is the location of Sydport, a former navy base (HMCS Protector) now converted to commercial use. The Canadian Coast Guard College is nearby at Westmount. Petroleum, bulk coal, and cruise ship facilities are also in Sydney Harbour.

Glace Bay, the second largest urban community in population, was the island's main coal mining centre until its last mine closed in the 1980s. Glace Bay was the hub of the Sydney & Louisburg Railway and a major fishing port. At one time, Glace Bay was known as the largest town in Nova Scotia, based on population.

Port Hawkesbury has risen to prominence since the completion of the Canso Causeway and Canso Canal created an artificial deep-water port, allowing extensive petrochemical, pulp and paper, and gypsum handling facilities to be established. The Strait of Canso is completely navigable to Seawaymax vessels, and Port Hawkesbury is open to the deepest-draught vessels on the world's oceans. Large marine vessels may also enter Bras d'Or Lake through the Great Bras d'Or channel, and small craft can use the Little Bras d'Or channel or St. Peters Canal. While commercial shipping no longer uses the St. Peters Canal, it remains an important waterway for recreational vessels.

The industrial Cape Breton area faced several challenges with the closure of the Cape Breton Development Corporation's (DEVCO) coal mines and the Sydney Steel Corporation's (SYSCO) steel mill. In recent years, the Island's residents have tried to diversify the area economy by investing in tourism developments, call centres, and small businesses, as well as manufacturing ventures in fields such as auto parts, pharmaceuticals, and window glazings.

While the Cape Breton Regional Municipality is in transition from an industrial to a service-based economy, the rest of Cape Breton Island outside the industrial area surrounding Sydney-Glace Bay has been more stable, with a mixture of fishing, forestry, small-scale agriculture, and tourism.

Tourism in particular has grown throughout the post-Second World War era, especially the growth in vehicle-based touring, which was furthered by the creation of the Cabot Trail scenic drive. The scenery of the island is rivalled in northeastern North America by only Newfoundland; and Cape Breton Island tourism marketing places a heavy emphasis on its Scottish Gaelic heritage through events such as the Celtic Colours Festival, held each October, as well as promotions through the Gaelic College of Celtic Arts and Crafts.

Whale-watching is a popular attraction for tourists. Whale-watching cruises are operated by vendors from Baddeck to Cheticamp. The most popular species of whale found in Cape Breton's waters is the Pilot whale.

The island's primary east-west road is Highway 105, the Trans-Canada Highway, although Trunk 4 is also heavily used. Highway 125 is an important arterial route around Sydney Harbour in the Cape Breton Regional Municipality. The Cabot Trail, circling the Cape Breton Highlands, and Trunk 19, along the island's western coast, are important secondary roads. The Cape Breton and Central Nova Scotia Railway maintains railway connections between the port of Sydney to the Canadian National Railway in Truro

The Cabot Trail is a scenic road circuit around and over the Cape Breton Highlands with spectacular coastal vistas; over 400,000 visitors drive the Cabot Trail each summer and fall. Coupled with the Fortress of Louisbourg, it has driven the growth of the tourism industry on the island in recent decades. The Condé Nast travel guide has rated Cape Breton Island as one of the world's best island destinations.

Traditional music

Cape Breton is well known for its traditional fiddle music, which was brought to North America by Scottish immigrants during the Highland Clearances. The traditional style has been well preserved in Cape Breton, and céilidhs have become a popular attraction for tourists. Inverness County in particular has a heavy concentration of musical activity, with regular performances in communities such as Mabou and Judique. Judique is recognized as 'Baile nam Fonn', (literally: Village of Tunes) or the 'Home of Celtic Music', featuring the Celtic Music Interpretive Centre. Performers who have received significant recognition outside of Cape Breton include Angus Chisholm, Buddy MacMaster, Joseph Cormier[36][37], first Cape Breton fiddler to record an album made available in Europe (1974)[38], Lee Cremo, Bruce Guthro, Natalie MacMaster, Ashley MacIsaac, The Rankin Family, Aselin Debison, Gordie Sampson, Dawn and Margie Beaton, also known as "The Beaton Sisters", and the Barra MacNeils. The Margaree's of Cape Breton also serve as a large contributor of fiddle music celebrated throughout the island. This traditional fiddle music of Cape Breton is studied by musicians around the world, where its global recognition continues to rise.

The Men of the Deeps are a male choral group of current and former miners from the industrial Cape Breton area.

Film and television

- My Bloody Valentine (1981) directed by George Mihalka

- The Bay Boy (1984) starring Kiefer Sutherland

- Squanto: A Warrior's Tale (1994) starring Adam Beach

- Margaret's Museum (1995) starring Helena Bonham Carter

- The Hanging Garden (1997) directed by Thom Fitzgerald

- Pit Pony (1997), TV movie and series adapted from the novel by Joyce Barkhouse

- New Waterford Girl (1999) directed by Allan Moyle

- Marion Bridge (2002) directed by Wiebke von Carolsfeld

- Take This Waltz (2011) starring Michelle Williams and Seth Rogen, filmed partially in Cape Breton

- The Book of Negroes (2015) starring Cuba Gooding Jr. adapted from the novel of the same name by Lawrence Hill

Notable people

Cape Breton artists who have been recognized with major national or international awards include actor Harold Russell of North Sydney, who won an Academy Award in 1946 for his portrayal of Homer Parrish in The Best Years of Our Lives, and Lynn Coady and Linden MacIntyre of Inverness County, who are both past winners of the Giller Prize for Canadian literature. The Rankin Family and Rita MacNeil have recorded multiple albums certified as Double Platinum by Music Canada.[39]

People from Cape Breton have also achieved a number of firsts in Canadian politics and governance. These include Mayann Francis of Whitney Pier, the first Black Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, Isaac Phills of Sydney, Nova Scotia, the first person of African descent to be awarded the Order of Canada,[40] and Elizabeth May of Margaree Harbour, the first member of the Green Party of Canada elected to the House of Commons of Canada.

Cape Breton Island is also home to YouTube weather forecaster Frankie MacDonald, who has over 200,000 subscribers. He accurately predicted an magnitude 7 earthquake in New Zealand in November 2016.

American artists like sculptor Richard Serra, composer Philip Glass and abstract painter John Beardman spent part of the year on Cape Breton Island.

Steve Arbuckle is a Canadian-born actor born in Cape Breton Island.

Director Ashley McKenzie's 2016 film Werewolf is set on the island and features local actors; McKenzie grew up on the island.[41]

Bruce Guthro; Lead singer and guitarist of the former Scottish Celtic band Runrig, which disbanded in 2018 after 46 years. Guthro resides in Hammonds Plains, Nova Scotia.

Dylan Guthro; musician. Son of Bruce Guthro.

Photo gallery

Cabot's Landing, Victoria County, commemorating the "first land seen" by explorer John Cabot in 1497

Cabot's Landing, Victoria County, commemorating the "first land seen" by explorer John Cabot in 1497

A bulk carrier in the Strait of Canso docked at the Martin Marietta Materials quarry at Cape Porcupine

A bulk carrier in the Strait of Canso docked at the Martin Marietta Materials quarry at Cape Porcupine

Smelt Brook on the northern shore

Smelt Brook on the northern shore Entering Cape Breton Island from Canso Causeway

Entering Cape Breton Island from Canso Causeway Seal Island Bridge in Victoria County, the 3rd-longest in Nova Scotia

Seal Island Bridge in Victoria County, the 3rd-longest in Nova Scotia Sydney Harbour with Point Edward, Westmount, and downtown Sydney visible

Sydney Harbour with Point Edward, Westmount, and downtown Sydney visible

See also

Notes

- CBIT-TV (CBC) existed from 1972 until 31 July 2012, when the CBC closed its over-the-air analog transmitters in small markets. It produced a local news broadcast until 1991, when local news shows were consolidated to Halifax. The CBC Nova Scotia television signal, which originates from Halifax, is now available only by cable or satellite providers.[35]

References

Citations

- Table from Statistics Canada – CBRM (Census Profile, 2011 Census)

- Table of demonyms in Canada Archived 30 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Table from Statistics Canada (Census Profile, 2011 Census)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Ganong, William Francis (1964). Crucial Maps in the Early Cartography and Place-nomenclature of the Atlantic Coast of Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 37.

- de Souza, Francisco; Tratado das Ilhas Novas, 1570

- Roger Sarty and Doug Knight. Saint John Fortifications: 1630–1956. New Brunswick Military Heritage Series. 2003. p. 18.

- Nichols, 2010. p. xix

- Canadian Military Heritage Archived 8 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine; vol.1, Chapter 6: Soldiers of the Atlantic Seaboard, p103. Government of Canada, 26 April 2004

- "The Acadians – Timeline". The Acadians. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2004. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- Samuel Weller Prenties. Narrative of a shipwreck on the island of Cape Breton, in a voyage from Quebec 1780

- Naval Chronicle. Vol. 11, p. 447

- Naval Chronicle, Vol. 14, p. 28

- C. J. MacGillivray. Timothy Hierlihy and his Times: The story of the Founder of Antigonish, Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia Historical Society., p.40

- C. J. MacGillivray. Timothy Hierlihy and his Times: The story of the Founder of Antigonish, N.S. Nova Scotia Historical Society., p.42

- Maj.-Gen. Eyre Massey to General Sir Henry Clinton. 13 June 1778

- Thomas B. Akins. (1895) History of Halifax. Dartmouth: Brook House Press.p. 82

- Morgan, R. J. (1979). "Mathews, David". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Morgan, R. J. (1987). "Despard, John". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. VI (1821–1835) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Despard, John; The Companion to British History, Routledge

- Krause, Eric R. (30 July 2014). "Fortress of Louisbourg Visitation Numbers". Krause House Info-Research Solutions. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- Kennedy, Michael (2001). "Gaelic Report" (PDF). Nova Scotia Museum. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- Emmerson, George (1976). The Scottish tradition in Canada. Reid, W. Stanford (William Stanford), 1913–1996. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart in association with the Multiculturalism Program, Dept. of the Secretary of State of Canada and the Pub. Centre, Supply and Services Canada. ISBN 0771074433. OCLC 2678091.

- Dunn, Charles (1968). Highland Settler: A Portrait of the Scottish Gael in Nova Scotia. University of Toronto Press. pp. 3–4.

- Kennedy, Michael (2001). "Gaelic Report" (PDF). Nova Scotia Museum. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- "Great Scots: The past comes to life at Highland Village Museum". The Chronicle Herald. 1 June 2014. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "History of Cape Breton Island". The Cabot Trail's Wilderness Resort on Cape Breton Island. 8 February 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Kennedy, Michael (2001). "Gaelic Report" (PDF). Nova Scotia Museum. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- Kennedy, Michael (2001). "Gaelic Report" (PDF). Nova Scotia Museum. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CD&Code1=1217&Geo2=PR&Code2=12&Data=Count&SearchText=Cape%20Breton&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&TABID=1&B1=All

- McEwan, Emily (2017). "Contrasting Gaelic Identities". Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- Table from Statistics Canada – Cape Breton & Richmond Counties (Nova Scotia Statistics Agency)

- Table from Statistics Canada – Victoria & Inverness Counties (Nova Scotia Statistics Agency)

- Woman wants Cape Breton flag designed by her daughter recognized – Football Archived 13 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Cape Breton Post (23 November 2009). Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- "Revocation of licences for the rebroadcasting stations CBIT Sydney and CBKST Saskatoon and licence amendment to remove analog transmitters for 23 English- and French-language television stations". Decisions, Notices and Orders. Ottawa: Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. 17 July 2012. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012.

- "JOE CORMIER"., article from "ACADIAN FIDDLE".

- "Joseph Cormier"., biography from "NATIONAL ENDOWMENT for the ARTS".

- "Joseph Cormier - Scottish Violin Music From Cape Breton Island". Rounder Records, USA. "Vinyl album, 1974".

- "Gold/Platinum". Music Canada. Archived from the original (Searchable database) on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- "The North Bay Nugget – July 7, 1967". Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- "Cape Breton film gets 'overwhelming' reaction at Berlin film festival". CBC News. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

Sources

Books and journals

- Akins, Thomas B. (1895). History of Halifax. Dartmouth: Brook House Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barlow, Maude; May, Elizabeth (2000). Frederick Street: Life and Death on Canada's Love Canal. Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-00-638529-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Thomas J. (1922). Place-names of the province of Nova Scotia. Halifax: Royal Print & Litho.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Caplan, Ronald (1 June 1976). "Sydney Harbour in World War 2". Cape Breton's Magazine. Wreck Cove, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia: Breton Books (13): 27–40. ISSN 0319-4639. Retrieved 6 January 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Doyle, Bill (2011). Cape Breton Facts and Folklore. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55109-867-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Michael (1987). Justice Denied: The Law versus Donald Marshall. Toronto: Totem Books. ISBN 978-0-00-217890-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howe, C. D. (1955). The Canada Year Book 1955: The Official Statistical Annual of the Resources, History, Institutions, and Social and Economic Conditions of the Dominion (PDF). Ottawa: Canada Year Book Section Information Services Division.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacDonald, Herb (2012). Cape Breton Railways: An Illustrated History. Sydney, Nova Scotia: Cape Breton University Press. ISBN 978-1-897009-67-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morgan, Robert J. (2008). Ronald Caplan (ed.). Rise Again!: the Story of Cape Breton Island - Book One. Wreck Cove, Nova Scotia: Breton Books. ISBN 978-1-895415-81-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Public Archives of Nova Scotia (1967). "Place-Names and Places of Nova Scotia/with an introd. by Charles Bruce Fergusson". Halifax. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarty, Roger F. (2012). War in the St. Lawerance: The Forgotten U-boat Battles on Canada's Shores. Toronto: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-670-06787-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stevens, H. H. (1932). The Canada Year Book 1932: The Official Statistical Annual of the Resources, History, Institutions, and Social and Economic Conditions of the Dominion (PDF). Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics General Statistics Branch.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tennyson, B. D. (2004). Cape Bretoniana: an annotated bibliography. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tennyson, Brian Douglas; Sarty, Roger F. (2000). Guardian of the Gulf: Sydney, Cape Breton, and the Atlantic wars. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-4492-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winters, Robert. H. (1967). Canada Year Book 1967: Official Statistical Annual of the Resources, History, Institutions, and Social and Economic Conditions of the Dominion (PDF). Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics Canada Year Book Division.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

News media

- CP Special (20 November 1967). "March through Sydney: 20,000 protest DOSCO closing". The Toronto Daily Star. Toronto. p. 5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grimes, William (7 August 2009). "Donald Marshall Jr., Symbol of Bias, Dies at 55". The New York Times. New York. p. A20. Retrieved 11 January 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lebel, Ronald (18 October 1967). "Premier calls for government aid to keep Dosco going four months". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. pp. 1, 2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Loring, Rex (30 June 1958). "The marvellous microwave network". Scan. Toronto: CBC News Digital Archives. Retrieved 11 January 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacDonald, Randy (20 June 2011). "Holy Angels graduation "bittersweet" as Sydney school sets to close". CTV Atlantic News. Halifax. Retrieved 16 May 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milton, Steve (9 May 1996). "New name needed for AHL import: Something from the animal kingdom is very much in vogue now". The Hamilton Spectator. Hamilton, Ontario. p. C1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Special to the Star (23 November 1967). "Nova Scotia will buy Dosco plant, operate it until at least April '69". Toronto Daily Star. p. 1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spectator Staff (5 October 1996). "7,006 fill the Dog House: A large walkup crowd was entertained to Fight Night in Steeltown as the Hamilton Bulldogs officially took to the ice last night". The Hamilton Spectator. Hamilton, Ontario. p. C1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Star Staff (23 November 1967). "Nova Scotia will buy Dosco plant, operate it until at least April '69". Toronto Daily Star (2 Star ed.). Toronto. p. 1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Other online sources

- "Demographic Information". Planning and Development Department. Sydney, Nova Scotia: Cape Breton Regional Municipality. 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012.

- Environment Canada (2012a). "Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000: Sydney, Nova Scotia". National Climate Data and Information Archive. Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Environment Canada (10 May 2012). "Hourly Data: Sydney, Nova Scotia". National Climate Data and Information Archive. Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "History". Cape Breton Screaming Eagles. Montreal: Quebec Major Junior Hockey League. 2012. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012.

- Statistics Canada (2012a). "Cape Breton – Sydney, Nova Scotia (Code 0913) and Cape Breton, Nova Scotia (Code 1217030) (table). Census Profile". 2011 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-XWE. Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Statistics Canada (2012b). "Map: Cape Breton – Sydney (Population Centre), Nova Scotia". 2011 Census. Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Deibel, James; Norda, Jacob (2012). "Historical Weather for the Last Twelve Months in Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada". WeatherSpark. San Francisco: Vector Magic, Inc. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- CB-VRSB Staff (2012). "Sydney Academy". CB-VRSB Schools. Sydney, Nova Scotia: Cape Breton-Victoria Regional School Board. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kernaghan, Lois (2012). "University College of Cape Breton". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Toronto: Institute Historica/Dominion Institute. Archived from the original on 19 May 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Revocation of licences for the rebroadcasting stations CBIT Sydney and CBKST Saskatoon and licence amendment to remove analog transmitters for 23 English- and French-language television stations". Decisions, Notices and Orders. Ottawa: Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. 17 July 2012. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012.

- Dulmage, Bill (July 2012). "Nova Scotia CBIT-TV (CBC-TV), Sydney, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation". Television Station History. Toronto: Canadian Communications Foundation. Retrieved 26 December 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Radio History: CJCB-AM, Sydney, Maritime Broadcasting Ltd". Toronto: Canadian Communications Foundation. 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- Dulmage, Bill (2012a). "Radio History: CBI-AM (Radio One), Sydney, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation". Toronto: Canadian Communications Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dulmage, Bill (2011). "Radio History: CBI-FM (Radio Two), Sydney, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation". Toronto: Canadian Communications Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cape Breton Island. |

- Cape Breton Island Official Travel Guide