History of Dhaka

Dacca or Dhaka is the capital and one of the oldest cities of Bangladesh. The history of Dhaka begins with the existence of urbanised settlements in the area that is now Dhaka dating from the 7th century CE. The city area was ruled by the Buddhist kingdom of Kamarupa before passing to the control of the Sena dynasty in the 9th century CE.[2] After the Sena dynasty, Dhaka was successively ruled by the Turkic and Afghan governors descending from the Delhi Sultanate before the arrival of the Mughals in 1608. After Mughals, British ruled the region for 200 years until the independence of India. In 1947, Dhaka became the capital of the East Bengal province under the Dominion of Pakistan. After the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, Dhaka became the capital of the new state.

Etymology

.jpg)

There are several myths on the origin of the name Dhaka. One is that the name came following the establishment of Dhakeshwari temple by Raja Ballal Sena in the 12th century and Dhakeswari is the name of a Goddess. While others say that Dhakeshwari stands the meaning of Goddess of Dhaka; so the temple must have been named after the region. Another myths says that the Dhak (a membranophone instrument) is used as part of the Durga Puja festival in this temple and hence the name Dhaka. Yet another one says it came from the plant named Dhak (Butea monosperma) which was widely found in that area.[3]

The more credible theory comes from the source of Rajatarangini written by a Kashmiri Brahman, Kalhana.[3] It says the region was originally known as Dhakka. The word Dhakka means watchtower. Bikrampur and Sonargaon—the earlier strongholds of Bengal rulers were situated nearby. So Dhaka was most likely used as the watchtower for the fortification purpose.[3]

Kamarupa kingdom

Kamarupa kingdom, also known as Pragjyotisa, existed between 350 and 1140 CE.[4] According to the chronicle of Yogini Tantra, the southern boundary of the kingdom stretched up to the junction of Brahmaputra River and Shitalakshya River which covered the Dhaka region.[5] Pala Empire was the last dynasty to rule the whole Kamarupa region. During their reign between the 8th century until the late 11th century, Vikrampur, a region 12 miles from Dhaka, was their capital. The Pala rulers were Buddhists, but majority of their subjects were Hindus.[6]

Sena kingdom

Sena dynasty's founder, Hemanta Sen, was part of the Pala dynasty until their empire began to weaken.[7] He usurped power and styled himself king in 1095 AD. Then largely Hindu community populated the lower Dhaka region. Still existent localities like Laksmibazar, Banglabazar, Sutrapur, Jaluanagar, Banianagar, Goalnagar, Tantibazar, Shankhari Bazaar, Sutarnagar, Kamarnagar, Patuatuli and Kumartuli are the examples of settlements of Hindu craftsmen and professionals in that era.[8] According to popular legend, Dhakeshwari Temple was built by Ballal Sena, the second Sena ruler.[9] Another tradition says, there were fifty two bazaars and fifty three streets and the region acquired the name of "Baunno Bazaar O Teppun Gulli".[10]:94

Sultanate Period

Upon arrival of Islam in this region, Turkish and Afghan rulers reigned the area from the early 14th century until the late 16th century. An Afghan fort (also known as Old Fort of Dhaka) was built at that time which was later converted to the present-form of Dhaka Central Jail in 1820 by the British.[11] A 17th-century historian, Mirza Nathan, described the fort in his book Baharistan-i-Ghaibi as "surrounded by mud walls and the largest and strongest in pre-Mughal era".[11]

In 1412, Shah Ali Baghdadi, a saint arrived in Delhi and then came to Dhaka where he became a disciple of Shah Bahar of the Chistia order.[12] His tomb is still at Mirpur on the outskirts of Dhaka.

Binat Bibi Mosque was built in 1454 at Narinda area of Dhaka during the reign of the Sultan of Bengal, Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah (r. 1435 – 1459).[13] It is the oldest brick structure that still exists in the city.[14]

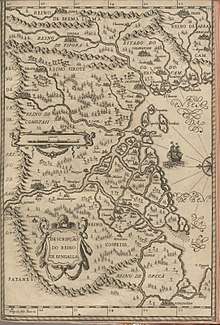

According to the inscription found near the present-day Central Jail area, the gate of Naswallagali Mosque was renoveated in 1459.[8][15] Around 1550 a Portuguese historian, João de Barros, first inserted Dhaka into the map in his book Décadas da Ásia (Decades of Asia).[8]

Mughal rule and rise as the capital of Bengal

Dhaka came into the domain of Mughal Empire during the reign of Emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605) after the Battle of Tukaroi.[16] Dhaka was referred as a Thana (a military outpost).[17] Dhaka was situated in Bhati region which hosted several rebel forces led by Bara-Bhuiyans from mid to late 16th century. After the leader of Bara-Bhuiyans, Musa Khan, was subdued by Mughal General Islam Khan Chisti in 1608, Dhaka again went directly under control of Mughals.

The newly appointed subahdar of Bengal Subah, Islam Khan transferred the capital from Rajmahal to Dhaka in 1610.[8] He also renamed Dhaka as Jahangirnagar (City of Jahangir) after the Emperor Jahangir. Due to its location right beside some main river routes, Dhaka was an important centre for business. The Muslin fabric was produced and traded in this area. He successfully crushed the regional revolts in Jessore, Bakla (present days Barisal) and Bhulua (present days Noakhali) and brought almost the entire province under the Mughal domain.[18]

As the next subahdar, Prince Shuja built Bara Katra between 1644 and 1646 in Dhaka to serve as his official residence. He also patronised building of Hussaini Dalan, a Shia shrine though he himself was a Sunni. In the late 1640s, for personal and political reasons, he moved the capital back to Rajmahal. Dhaka became a subordinate station.

Due to political turmoil, Emperor Aurangzeb sent Mir Jumla to deal with Prince Shuja.[19] He pursued Shuja up to Dhaka and reached the city on 9 May 1660. But Shuja had already fled to Arakan region. As Jumla was ordered to become the next subahdar of Bengal Subah, Dhaka was again made the capital of the region.[19] He was engaged in construction activities in Dhaka and its suburbs – two roads, two bridges and a network of forts. A fort at Tangi-Jamalpur guarded one of the roads connecting Dhaka with the northern districts which is now known as Mymensingh Road.[19] He built Mir Jumla Gate at the northern border to defend the city from the attacks of Magh pirates. Italian traveller Niccolao Manucci came to Dhaka in 1662–63.[20] According to him, Dhaka had a large number of inhabitants compare to the size of the city. Most of the houses were built of straw. There were only two kuthis – one of the English and the other of the Dutch. Ships were loaded with fine white cotton and silk fabrics. A large number of Christians and white and black Portuguese resided in Dhaka.[20]

Thomas Bowrey, a British merchant sailor, visited Dhaka in the 1670s. In his book, A Geographical Account of Countries Round the Bay of Bengal, he mentioned:[21]

The City of Dhaka is a very large, spacious one, but stands on low, marshy, swampy ground, and the water of that ground is very brackish, which is the only inconvenience. It has, however, some very fine conveniences that compensate, having a very fine and large river that runs close by the city walls, navigable by ships of 500 or 600 tonnes burden. The water of the river, being an arm of the Ganges, is extraordinarily good, but is some distance for fetching and carrying for some residents of the city, the city being not less than 40 English miles in circumference. It is an admirable city for its greatness, for its magnificent buildings, and the multitude of its inhabitants. A very great and potent, permanent, and paid army is based here, in a constant state of readiness. Also, many large, strong, and stately elephants, trained for battle, which are kept close to the palace.

Construction of Lalbagh Fort was commenced in 1678 by Prince Muhammad Azam during his 15-month-long governorship of Bengal, but before the work could complete, he was recalled by Emperor Aurangzeb.

The largest expansion of the city took place under the next Mughal subahdar Shaista Khan (1664–1688). The city then stretched for 12 miles in length and 8 miles in breadth and is believed to have had a population of nearly a million people.[22] The Chawk Mosque, Babubazar Mosque, Sat Gumbad Mosque, Choto Katra were originally built during this period. He also built tombs of Bibi Pari, Bibi Champa and Dara Begum.[8] A French traveller, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, arrived Dhaka on 13 January 1666 and met Shaista Khan.[10]:144 He referred Shaista Khan as "the uncle of King Aurangzeb and the cleverest man in all his kingdom".[10]:144

Prince Azim-ush-Shan became the subahdar of Bengal Subah in 1697. Due to conflict with Diwan Murshid Quli Khan,[23] he transferred the capital from Dhaka to Rajmahal and then to Patna in 1703.[24] Murshid Khan also shifted his office to Mauksusabad (later renamed it to Murshidabad).[25]

Economy

Under the Mughal Empire which had 25% of the world's GDP, Bengal Subah generated 50% of the empire's GDP and 12% of the world's GDP.[26] Bengal, the empire's wealthiest province,[26] was an affluent region now currently with a Bengali Muslim majority and Bengali Hindu minority. According to economic historian Indrajit Ray, it was globally prominent in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding.[27]

The capital Dhaka had an estimated 80,000 skilled textile weavers. It was an exporter of silk and cotton textiles, steel, saltpeter, and agricultural and industrial produce.[26]

Portuguese settlements

In Bengal region, the Portuguese made the principal trading centre in Hooghly.[28] Besides, they made small settlements in Dhaka in about 1580.[29]:88 Ralph Fitch, an English traveller, recorded in 1586 that Portuguese traders were involved in shipping rice, cotton and silk goods.[29] Tavernier mentioned about churches built in Dhaka by Portuguese Augustinian missionaries. In 1840, James Taylor, the civil surgeon of Dhaka, wrote that the oldest existing Portuguese structure today, Church of Our Lady of Rosary in Tejgaon, was built in 1599 by the missionaries.[30][31] But according to historian Ahmad Hasan Dani, it was built in 1677.[30] Joaquim Joseph A. Campos, an editor of Asiatic Society of Bengal, mentioned other Portuguese churches in Dhaka – Church of St. Nicholas of Tolentino, Church of the Holy Ghost and Church of our Lady Piety.[29]:247–250 The Portuguese officially established a mission in Dhaka in 1616.[30]

Sebastien Manrique, a Portuguese missionary and traveler, visited Dhaka in September 1640 and spent about 27 days around the area.[28] According to him, the city extended along the Buriganga river for over four and a half miles from Maneswar to Narinda and Fulbaria. Christian communities lived around these suburbs in the west, east, and north. He further mentioned, "a small but beautiful church with a convent" in Dhaka. In his words,

This is the chief city in Bengala and the seat of the principal Nababo or viceroy, appointed by the emperor, who bestowed this viceroyalty, on several occasions, on one of his sons. It stands in a wide and beautiful plain on the banks of the famous and here fructifying Ganges river, beside which the City stretches for over a league and a half.[28]

In his conquest of Chittagong from the Arakanese (1665–1666), Shaista Khan received 40 ships from the Portuguese for his naval fleet.[30] A section of the Portuguese came from Sandwip and Arakan and settled on the bank of Ichamati River (about 25 kilometres (16 mi) south of Dhaka) at the present-day Muktarpur–Mirkadim area in Munshiganj, which bears its historical name of Feringhi Bazar.[29]:89 They were mainly involved in the salt trade.[30]

In 1713, priest Anthony Barbier spent Christmas at a church in Narinda, a neighborhood in Dhaka.[30] In the 1780 map of English geographer James Rennell, the Portuguese settlers in Dhaka were within proximity of that church (present-day Narinda-Laxmibazar area).[30]

Nawab era

Around 1716–1717, Murshid Quli Khan became the Nazim (Governor) of Bengal and Orissa ruling the region from Murshidabad. The position of Naib Nazim (Deputy Governor) was created to administer the region of eastern Bengal from Dhaka, known as Dhaka Niabat.[25] They were directly appointed by the governor. The first Naib Nazim of Dhaka was Khan Muhammad Ali Khan.[32] The period 1716–1757, from the reign of Murshid Quli Khan to Sirajuddaula, is referred as the Nawabi Era.[33] The last governor Sirajuddaula lost control to the British in the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Since then the office of Naib Nazim of Dhaka was held by one favored by the Fort William Council.[33] It was shorn of revenue and administrative powers from 1765 to 1822, holding only the title and a small allowance from 1822 to 1843.[25] The last Naib Naim Ghaziuddin Haider, known as Pagla Nawab, died without leaving any heir in 1843 and the title of Naib Nazim became extinct.[34]:34

The Naib Nazims initially resided in Islam Khan's fort (now located in the premises of the Old Dhaka Central Jail). After the British took control of the fort, the Naib Nazims moved to the Bara Katra (Great Caravenserai Palace).[35] In 1766, the Nimtali Kuthi became the official residence of the Naib Nazims.[36] Besides the Nimtali Kuthi, two other notable constructions during the period were Chowk Bazaar, built by Naib Nazim Mirza Lutfullah in 1728 and the Armanitola Mosque in 1735.[25]

Armenian settlements

The Armenians settled in Dhaka in the early 18th century.[37] They established trade ties in jute and leather with Mughals and Nawabs.[38] The Armenian Church (Church of Holy Resurrection) built in 1781 in Armanitola area bears the evidence of their presence. Since the British started ruling Bengal in 1757, Armenians slowly moved out of this area. The Pogose School, the first private school in Dhaka, was founded in the 1830s by Nicholas Pogose, an Armenian merchant.[39] By 1868, five of the six European zamindars in Dhaka were Armenians – Nicholas Pogose, GC Paneati, J Stephan, JT Lucas and W Harney.[40] English educational and social reformer Mary Carpenter visited Dhaka in December 1875, hosted by the Pogose family.[41] The last surviving Armenian, Michael Joseph Martin (Mikel Housep Martirossian), also the last resident warden of the Armenian Church, left Dhaka by 2018.[42][39][43][44]

British East India Company rule (1793—1857)

The English formally established their factories in Dhaka in 1668.[10]:144 The English traders were already in the city as early as in 1666 when Tavernier visited.[10]:144 William Hedges, the first governor of East India Company in Bengal, arrived Dhaka on 25 October 1682 and met Shaista Khan.[10]:156 After the Battle of Buxar in 1765, per the Treaty of Allahabad, East India Company was appointed the imperial tax collector of the province Bengal-Bihar-Orissa by the Mughal emperor. The company was still a subject of the Mughal empire. But it took complete control in 1793 when Nizamat (Mughal appointed governorship) was abolished. The city then became known by its anglicised name, Dacca. Owing to the war, the city's population shrank dramatically in a short period of time.[45] Although an important city in the Bengal province, Dhaka remained smaller than Kolkata, which served as the capital of British India for a long period of time. Under British rule, many modern educational institutions, public works and townships were developed. A modern water supply system was introduced in 1874 and electricity supply in 1878.[46] The Dhaka Cantonment was established near the city, serving as a base for the soldiers of the British Indian Army. Dhaka served as a strategic link to the frontier of the northeastern states of Tripura and Assam.

Charles D'Oyly was the District Collector of Dhaka from 1808 to 1811. He made a good collection of painting folios of Dhaka in the book, Antiquities of Dacca.[47] These paintings exhibited much of the ruins of Dhaka from the Mughal era. Short historical accounts of all the paintings was appended. James Atkinson wrote these accounts, accompanied by engravings done by Landseer.

In 1835, Dhaka College was established as an English school by the then Civil Surgeon Dr. James Taylor.[48] It received the college status in 1841. Local Muslim and Hindu students as well as Armenians and Portuguese were among the first graduates.[48]

Horse-driven carriages were introduced in Dhaka as public transport in 1856.[49] The number of carriages increased from 60 in 1867 to 600 in 1889.[49]

Rise of Dhaka Nawab Estate

Under the Permanent Settlement of Bengal enactment by Charles Cornwallis in 1793, the Company government and the Bengali zamindars agreed to fix revenues to be raised from land.[50] As a result, Dhaka Nawab Estate grew to become the largest zamindari in Eastern Bengal. It was founded by Kashmir origin merchant Khwaja Hafizullah Kashmiri and his nephew Khwaja Alimullah.[51] A French trading centre is converted as the residence of the Dhaka Nawabs in 1830.[52] It was later constructed into a palace and named Ahsan Manzil. The estate paid Rs 320,964 as per agreement to the Company government in 1904.[51] In 1952 the Estate was abolished according to the East Bengal Estate Acquisition and Tenancy Act.[51]

British Raj rule (1858—1947)

Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857, British East India Company's ruling ended and the British Crown took direct control of the region in 1858. Dacca Municipality was established on 1 August 1864.[53] At that time the area of Dhaka was 20.72 square kilometres with a population of around 52,000.[54]

Buckland Bund was constructed under a scheme by the then City Commissioner Charles Thomas Buckland in 1864 to protect Dhaka from flooding and river erosion.[55]

In 1860, the first printing press Bangala Jantra was set up in Dhaka and also Dhaka's first periodical Kabita Kusumabali was founded in the same year.[56] Dhaka's first theatre group, Purbabanga Rangabhumi, was established in the 1870s.[56] Dhaka Prakash, the first Bengali language newspaper in Dhaka, was published on 7 March 1861.[57]

In 1885, the railway line between Dhaka and Narayanganj was built.[49] Mymensingh was connected to Dhaka in 1889.[15] Private cars were owned from the 1910s and the taxis and rickshaws were introduced in the 1930s.[49]

The earliest records of Dhaka being hit by tornados were on 7 April 1888 and 12 April 1902 which killed 118 and 88 respectively.[58]

On 16 March 1892, a professional balloonist, Jeanette Van Tassel, invited by Nawab Ahsanullah, made an attempt to fly from the southern bank of Buriganga River to reach the roof Ahsan Manzil lying across the river. A newspaper had reported that thousands of locals gathered around the palace on the occasion. But a sudden gush of wind carried Tassel off to the Ramna Garden in Shahbagh where she got critically injured falling on the ground. She died later in a hospital and was buried in Narinda Christian graveyard.[59][60]

The then Viceroy of India Lord Curzon visited Dhaka on 18-19 February 1904, hosted by the Nawab family. He laid the foundation stone of Curzon Hall.[61] In July 1905, he decided to take effect the Partition of Bengal and Dhaka became the capital of the new province, Eastern Bengal and Assam, on 16 October.[62] Joseph Bampfylde Fuller entered on his office in Dhaka as the first Lieutenant-Governor of the region.[63] The partition was revoked in 1911 and Dhaka became a district town on 1 April 1912.[62]

The 20th session of All India Muhammadan Educational Conference was held at Ishrat Manzil, in present-day Shahbag area in Dhaka during 27—30 December 1906. On the final day, the All-India Muslim League political party was formed, with the aim of the establishment of a separate Muslim-majority nation-state.[64]

Eden College was founded in 1880. Narendra Narayan Roy Choudhury, landlord of the Baldah Estate, built Baldha Garden in 1909. University of Dhaka was established in 1921.[15] Philip Hartog became the first vice-chancellor of the university. Ahsanullah School of Engineering (now Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology) was established in 1912 under a substantial grant and patronage from Dhaka Nawab Family.[65]

East Bengal's (later East Pakistan's) capital (1947—1971)

Following the Partition of India in August 1947, Dhaka became the capital of East Bengal under the Dominion of Pakistan. The city witnessed serious communal violence that left thousands of people dead. A large proportion of the city's Hindu population departed for India, while the city received hundreds of thousands of Muslim immigrants from the Indian states of West Bengal, Assam and Bihar. Population increased from 335,925 in 1951 to 556,712 in 1961 registering an increase of 65.7 percent.[66][67] As the centre of regional politics, Dhaka saw an increasing number of political strikes and incidents of violence. The proposal to adopt Urdu as the sole official language of Pakistan led to protest marches and strikes involving hundreds of thousands of people in Bengali Language Movement. The protests soon degenerated into widespread violence after police firing killed students who were demonstrating peacefully. Martial law was imposed throughout the city for a long period of time.

The arrest of the Bengali politician Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1968 would also spark intensive political protests and violence against the military regime of Ayub Khan. The 1970 Bhola cyclone devastated much of the region, killing numerous people. More than half the city of Dhaka was flooded and waterlogged, with millions of people marooned. The same year, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman won a landslide victory in general election. He was elected as the next president of Pakistan. However, the West Pakistan's military rulers and even the largest opposition party's (PPP) leader Zulfiker Ali Bhutto refused to hand over the presidency to East Pakistan leadership. The following year saw Sheikh Mujib hold a massive nationalist gathering on 7 March 1971 at the Race Course Ground that attracted an estimated one million people. Galvanising public anger against ethnic and regional discrimination and poor cyclone relief efforts from the central government, the gathering preceded near total consensus among East Pakistan population for independent movement. In response, on 25 March 1971 in the middle of the night, the Pakistan Army launched Operation Searchlight, which led to the arrests, torture and killing of hundreds of thousands of people – just in that night alone. As a result, on behalf of East Pakistan leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, a Bengali army Major named Ziaur Rahman (later General and President) declared Bangladesh's independence on 26 March 1971. This resulted in further mass genocide of approximately 3 million people. Citizens and intellectuals from Dhaka was the largest victim of this mass genocide. The fall of the city to the Indian Army on 16 December 1971 marked the creation of the independent state of Bangladesh. Dhaka became the capital of Bangladesh.

Several prominent architectural development took place in Dhaka during this period. Holy Family Hospital was built in March 1953.[62] New Market was established in Azimpur in 1954.[62] Dhaka College was moved to Dhanmondi in July 1956.[62] Kamalapur railway station was established in 1969.[68]

Post-independence of Bangladesh (1971—present)

| Historical population | |

|---|---|

| Year | Pop. |

| 1801 | 200,000 |

| 1840 | 51,636 |

| 1872 | 69,212 |

| 1881 | 79,076 |

| 1911 | 125,000 |

| 1941 | 239,000 |

| 1951 | 336,000 |

| 1961 | 556,000 |

| 1974 | 1,680,000 |

| 1981 | 3,440,000 |

| 1991 | 6,150,000 |

| 2013 | 14,399,000 |

Despite independence, political turmoil continued to plague the people of Dhaka. The Pakistan Army's operations had killed or displaced millions of people, and the new state struggled to cope with the humanitarian challenges. The year 1975 saw the killing of Sheikh Mujib and three military coups. The city would see the restoration of order under military rule, but political disorder would heighten in the mid-1980s with the pro-democracy movement led by the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party. Political and student strikes and protests routinely disrupted the lives of Dhaka's people. However, the post-independence period has also seen a massive growth of the population, attracting migrant workers from rural areas across Bangladesh. A real estate boom has followed the development of new settlements such as Gulshan, Banani and Motijheel. Dhaka hosted the inaugural summit of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (1985), the D8 group summit (1999) and three South Asian Games events (1985, 1993 and 2010).[69]

In 1982, the English spelling of the city was officially changed from Dacca to Dhaka.[70]

In 1983, City Corporation was created to govern Dhaka and its population reached 3,440,147 and it covered an area of 400 square kilometres.[54] The city was divided into 75 wards. Under new act in 1993 the first election was held in 1994 and Mohammad Hanif became the first elected Mayor of Dhaka.[71] In 2011, Dhaka City Corporation was split into two separate corporations – DCC North and DCC South[72] and in 2015 election Annisul Huq and Sayeed Khokon were elected as the mayors of the respective corporations.[73]

As of 2019, Dhaka has an estimated population of more than 18 million people, making it the largest city in Bangladesh and the 13th largest city in the world.[74]

References

- "Painting - De Fabeck, Frederick William Alexander - V&A Search the Collections". collections.vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- Dhaka City Corporation (5 September 2006). "Pre-Mughal History of Dhaka". Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- Mamoon, Muntassir (2010). Dhaka: Smiriti Bismiritir Nogori. Anannya. p. 94.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Kamarupa". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Allen, Basil Copleston (2009) [First published 1912]. Eastern Bengal District Gazetteers: Dacca. p. 18. ISBN 978-81-7268-194-4.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Pala Dynasty". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Sena Dynasty". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Dhaka". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Dhakeshwari Temple". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Bradley-Birt, Francis Bradley (1906). The Romance of an Eastern Capital. Theclassics Us. ISBN 9781230376257.

- "::: Star Campus". www.thedailystar.net. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Shah Ali Baghdadi %28R%29". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Binat Bibi Mosque". ArchNet Digital Library. Archived from the original on 1 March 2006. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- "From Jahangirnagar to Dhaka". www.thedailystar.net. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- Mamoon, Muntassir (2010). Dhaka: Smiriti Bismiritir Nogori. Anannya. p. 305. ISBN 978-9844121041.

- The History of India: The Hindú and Mahometan Periods By Mountstuart Elphinstone, Edward Byles Cowell, Published by J. Murray, Calcutta 1889, Public Domain

- Akbarnama

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Islam Khan Chisti". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Mir Jumla". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Manucci, Niccolao". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Steel, Tim (18 April 2015). "Dhaka, before the fall". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- "Dhaka Under the Mughals – Dhaka South City Corporation". Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- Diwans were separate positions for financial and revenue administration and they were directly appointed by the Emperor.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Azim-us-Shan". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Naib Nazim". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star (Opinion). 31 July 2015.

- Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. pp. 57, 90, 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Manrique, Sebastien". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Campos, Joaquim Joseph (1919). History of the Portuguese in Bengal. Asian Educational Services.

- "The Portuguese in Dhaka". The Daily Star. 22 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- Taylor, James (1840). A sketch of the topography & statistics of Dacca. Oxford University. Calcutta : G.H. Huttmann, Military Orphan Press.

- Mamoon, Muntassir (2010). Dhaka: Smiriti Bismiritir Nogori. Anannya. pp. 143–144.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Nawab". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Allen, Basil Copleston (1912). Dacca : Eastern Bengal District Gazetteers. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 9788172681944.

- "Soolteen Sahib of Dhaka". The Daily Star. 31 December 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Nimtali Palace". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Armenians, The". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- The Armenian Church: Legacy of a Bygone Era by theindependent Archived 6 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Shafiq Alam (27 February 2009). "Bangladesh's Last Armenian Prays For Unlikely Future". Armenian Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator Singapore.

- Clay, AL (1898). Leaves from a diary in East Bengal. London. pp. 104–105.

- "The Pogose School: An Armenian legacy in Old Dhaka". The Daily Star. 13 May 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Waqar A Khan (4 June 2018). "The Merchant-Prince Of East Bengal". The Daily Star. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- Alastair Lawson (10 January 2003). "The mission of Dhaka's last Armenian". BBC News. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- "The last of the Armenians". The Daily Star. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- Dhaka City Corporation (5 September 2006). "Dhaka Under the East India Company". Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- Dhaka City Corporation (5 September 2006). "History of Dhaka Under the British". Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Antiquities of Dacca". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Brief History of Dhaka College". Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- "From Elephants to Motor Cars". The Daily Star. 24 September 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Permanent Settlement, The". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Dhaka Nawab Estate". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Ahsan Manzil". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Don't split Dhaka, Khoka urges govt". UNBConnect. 12 November 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- Md Shahnawaz Khan Chandan (8 May 2015). "Reminiscing Dhaka's Legacy". The Daily Star.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Buckland Bund". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Purbabanga Rangabhumi and the beginning of theatre in Dhaka". The Daily Star. 6 January 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Dhaka Prakash". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Bangladesh Tornado Climatology". bangladeshtornadoes.org. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Bangladesh's First Balloonist". The Daily Star. 21 October 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Early History – Ladies of Skydiving". Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Dacca College". British Library. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Dani, Ahmad (1962), Dacca – A record of its changing fortunes, Mrs. Safiya S Dani, p. 119

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 830.

- "Establishment of All India Muslim League". Story Of Pakistan. 1 June 2003. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Khwaja Salimullah". World History. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- Census of Pakistan, bulletin no. 2, 1961, p. 18

- Dhaka City Corporation (5 September 2006). "History". Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- Ershad Ahmed (30 May 2008). "Dhaka". blogspot.com. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- "11th South Asian Games to start in January 2010". www.china.org.cn. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Abu Jar M Akkas (1 April 2018). "Place names and their spelling in English". New Age. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Mayor Hanif's death anniversary today". The Daily Star. 28 November 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Hasan Jahid Tusher (18 October 2011). "Dhaka set to split into two". The Daily Star. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- "3 new mayors renew pledges to make cities livable". The News Today. 7 May 2015.

- "Demographia World Urban Areas, 14th Annual Edition" (PDF). April 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2018.