Health in Bangladesh

Health levels remain relatively low in Bangladesh, although they have improved recently as poverty (31% at 2010[1]) levels have decreased.

Health infrastructure

To ensure equitable healthcare for every resident in Bangladesh, an extensive network of health services has been established. Infrastructure of healthcare facilities can be divided into three levels: medical universities, medical college hospitals, and specialty hospitals exist at the tertiary level. District hospitals, maternal and child welfare centers are considered to be on the secondary level. Upazila (subdistrict) health complexes, union health & family welfare centers, community clinics (lowest-level healthcare facilities) are the primary level healthcare providers. Various NGOs (non-government organizations) and private institutions also contribute to this intricate network .[2][3]

The total expenditure on healthcare as a percentage of Bangladesh's GDP was 2.37% in 2016.[4]

In the parliamentary budget of 2017-18, only the budget has been set for the health sector is 16 thousand 203 crore 36 lakhs Bangladeshi taka.[5]

There are 3 hospital beds per 10,000 people.[6] The general government expenditure on healthcare as a percentage of total government expenditure was 7.9% as of 2009 and the citizens pay most of their health care bills as the out-of-pocket expenditure as a percentage of private expenditure on health is 96.5%.[4] The doctor to population ratio is 1:2,000[7] and the nurse to population ratio is 1:5,000[7]

Hospitals

Medical schools

Health status

Demographics

Health indicators

- CDR – 5.35 /1000

- Maternal mortality ratio – 176 /100000

- IMR – 31 /1000 live births

- Under 5 MR – 38 /1000 live births

- Total Fertility Rate – 2.1

- Life expectancy at birth – 71 (m) and 73 (f)

- Fully immunized children – 52%

Health problems in Bangladesh

Due to huge number of population, Bangladesh faces double burden of diseases: Non-Communicable diseases: Diabetes, Cardiovascular diseases, Hypertension, Stroke, Chronic respiratory diseases, Cancer and Communicable diseases: Tuberculosis, HIV, Tetanus, Malaria, Measles, Rubella, leprosy and so on.[11]

The health problems of Bangladesh include communicable and non-communicable disease, malnutrition, environmental sanitation problems, and others.

Communicable disease

From historical aspect, it is known that Communicable diseases formed major bulk of total diseases in developing and tropical countries such as Bangladesh. By 2015 via Millennium development Goals, where communicable diseases were targeted, Bangladesh attained almost significant control on communicable diseases.[11] An expanded immunization programme against nine major diseases (TB, Tetanus, Diphtheria, Whooping cough, Polio, Hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenza type B, Measles, Rubella) was undertaken for implementation.

Tuberculosis

Background: Tuberculosis is one of the most dangerous chronic infectious diseases in Bangladesh. It is the major public health problem in of this country. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is commonly responsible organism of Tuberculosis. Its airborne disease spreads through the coughing of infected person. This disease is more prone to slum dwellers living in unhygienic condition. Tuberculosis mainly infects the lungs (Pulmonary Tuberculosis) with the symptoms of persistence cough, evening fever with sweating, chest pain, weakness, weight loss, hemoptysis etc. But it can also infect the other parts of the body (Extra Pulmonary Tuberculosis) like brain, kidneys and bones as well. In most of the cases patients infected with Tuberculosis have other concomitant infection. HIV is more common to them.[12]

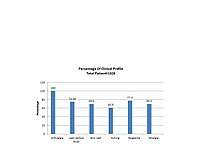

Present TB status of Bangladesh: According to WHO, 'Global TB Report 2017' total population was 165 million, Bangladesh is one of the world's 30 high TB burden country and near about 59170 people died due to Tuberculosis .Total estimated number of TB patient was 364000, among them male patient was recorded 236000 and female patient was 128000. In 2017 total case was notified 244201. Total new and relapse case was 242639. People are mainly suffering from pulmonary TB; it was 81% (197800 patients) of notified cases.[12]Still now, HIV is considered as the most deadly infectious disease all over the world. It suppresses the immune system of the body. So any kind of infection can be incubated into the body, HIV infected person can be easily infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

TB with HIV patient: Still now, HIV is considered as the most deadly infectious disease all over the world. It suppresses the immune system of the body. So any kind of infection can be incubated into the body, HIV infected person can be easily infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, it is HIV-TB co infection. In 2017, estimated number of the patient with HIV positive status tuberculosis was 540. Patient with HIV positive status (New and Relapse case) notified was 89, out of 540 HIV positive patients. Among 89 patient 84 patients took anti-retroviral therapy.

Drug Resistance: When micro-organism of TB causes resistance to Isoniazid or/and Rifampicin the most effective drugs of TB. If the organism causes resistance against both of 2 drugs then it is called Multi Drug resistance TB (MDR-TB). In 2017 estimated number of MDR was 8400, among them 5800 cases was notified and 944 patients were confirmed by laboratory test and 920 patients started immediate treatment. If any patient develops resistance against Isoniazid/ Rifampicin and one of the 2nd line antibiotic Fluoroquinolones (i.e, amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin), it’s called Extreme Drug Resistance tuberculosis (XDR-TB). In 2017, 6 patients were confirmed XDR-TB by laboratory diagnosis and all of them started treatment instantly. As 31 December 2017, countrywide a total 6420 MDR-TB patients were enrolled for treatment including 920. Among 920 patients, 425 patients were in 24 month regimen and 495 patients were 9 months regimen[13][12]

Bangladesh Combats with TB: Under Mycrobacterial Disease Control (MBDC) Unit of the Director-General Health Service (DGHS), National Tuberculosis Control Program (NTP) is working with a goal to eliminate Tuberculosis from Bangladesh. The NTP adopted DOTS (Directly Observed treatment Short Course) strategy during fourth Population and health Plan (1992-1998) and implemented it in field level in November 1993. This strategy reduced TB case significantly. The program achieved 70% new smear positive case reduction in 2006 and treated 85% of them since 2003. This program has successfully treated 95% of bacteriologically confirmed new pulmonary cases registered in 2016.

| Indicator | Milestone | Targets | ||

| SDG | End TB | |||

| Year | 2020 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 |

| Reduction of deaths due to tuberculosis ( Projected 2015 baselines (72450) in absolute number | 47092 | 18112 | 7245 | 3622 |

Table-1: Bangladesh Indicator in Line with End TB Strategy

In 2015 the TB case was noted 225/ per 100000 patient and Government of Bangladesh has taken the target of reduction of TB New cases 10/ per 100000 patients by 2035 that will be around 1650 cases.[13]

Non-communicable diseases of Bangladesh

However, recent statistics shows that non-communicable disease burden has increased to 61% of the total disease burden due to epidemiological transition. According to National NCD Risk Factor Survey in 2010, 99% of the survey population revealed at least one NCD risk factor and ~29% showed >3 risk factors .Social transition, rapid urbanization and unhealthy dietary habit are the major stimulating reasons behind high prevalence of non-communicable diseases in Bangladesh remarkably in under-privileged communities such as rural inhabitants, urban slum dwellers.[11][14][11][15]

Diabetes

Diabetes, one of four priority non-communicable diseases targeted by world leaders has become a major health problem globally (415 million adults with diabetes in 2015 and by 2040 that number will increase to 642 million). More than two third of diabetic adults (75%) are from low and middle income countries due to demographic changes, cultural transition and population ageing. Among dominant identified risk factor of burden of diseases in South Asian countries, diabetes is placed in seventh position. Bangladesh is placed in top tenth position (7.1 million) among countries with highest number of diabetes adults in the world. Therefore, co-jointly with India and Sri Lanka, Bangladesh constitutes 99.0% of the adult with high blood sugar in the South Asian region. Previous studies show that prevalence of diabetes is increasing significantly in the rural population of Bangladesh. It is also observed that females have higher prevalence of diabetes than male both in rural and urban areas. Lacks of self-care, unhealthy dietary habit, and poor employment rate are the considerable factors behind that higher prevalence of diabetes among females. However, compared to Western nations, the pattern of diabetes begins with the onset at a younger age, and the major diabetic population is non-obese. Such clinical differences, limited access to health care, increase life expectancy, ongoing urbanization and poor awareness among population increase the prevalence and risk of diabetes in Bangladesh [16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

Eye disease related to diabetes (diabetic retinopathy)

The prevalence of Diabetic retinopathy in Bangladesh is about one third of the total diabetic population (nearly 1.85 million) .These recent estimates are higher like western Countries and similar to Asian Malays living in Singapore. Sharp economic transition, urbanization, technology based modern life style, tight diabetes control guidelines and unwillingness to receive health care are thought to be the risk factors of diabetic retinopathy in Bangladesh.Unfortunately to attain that emerging health problem, the current capacity in the country to diagnose and treat diabetic retinopathy is very limited to a few centers. Till this year (2016), as per record of National Eye Care under HPNSDP (Health Population Nutrition Sector Development Program), 10,000 people with Diabetic Retinopathy have received services from Secondary and tertiary Hospitals where the screening programs have been established.[26][27][28]

Environmental sanitation

The most difficult problem to tackle in this country is perhaps the environmental sanitation problem which is multi-faceted and multi-factorial. The twin problems of environmental sanitation are lack of safe drinking water in many areas of the country and preventive methods of excreta disposal.

- Indiscriminate defecation resulting in filth and water born disease like diarrhea, dysentery, enteric fever, hepatitis, hook worm infestations.

- Poor rural housing with no arrangement for proper ventilation, lighting etc.

- Poor sanitation of public eating and market places.

- Inadequate drainage, disposal of refuse and animal waste.

- Absence of adequate MCH care services.

- Absence and/ or adequate health education to the rural areas.

- Absence and/or inadequate communications and transport facilities for workers of the public health.

Malnutrition

Bangladesh suffers from some of the most severe malnutrition problems. The present per capita intake is only 1850 kilo calorie which is by any standard, much below required need. Malnutrition results from the convergence of poverty, inequitable food distribution, disease, illiteracy, rapid population growth and environmental risks, compounded by cultural and social inequities. Severe undernutrition exists mainly among families of landless agricultural labourers and farmers with small holding.

Specific nutritional problems in the country are—

- Protein–energy malnutrition (PEM): The chief cause of it is insufficient food intake.

- Nutritional anaemia: The most frequent cause is iron deficiency and less frequently follate and vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Xerophthalmia: The chief cause is nutritional

deficiency of Vit-A.

- Iodine Deficiency Disorders: Goiter and other iodine deficiency disorders.

- Others: Lathyrism, endemic fluorosis etc.

Child malnutrition in Bangladesh is amongst the highest in the world. Two-thirds of the children under the age of five are under-nourished and about 60% of children under age six, are stunted.[29] As of 1985, more than 45 percent of rural families and 76 percent of urban families were below the acceptable caloric intake level.[30] Malnutrition is passed on through generations as malnourished mothers give birth to malnourished children. About one-third of babies in Bangladesh are born with low birth weight, increasing infant mortality rate, and an increased risk of diabetes and heart ailments in adulthood.[31] One neonate dies in Bangladesh every three to four minutes; 120 000 neonates die every year.[32]

The World Bank estimates that Bangladesh is ranked 1st in the world of the number of children suffering from malnutrition.[33][32] In Bangladesh, 26% of the population are undernourished[34] and 46% of the children suffers from moderate to severe underweight problem.[35] 43% of children under 5 years old are stunted. One in five preschool age children are vitamin A deficient and one in two are anaemic.[36] Women also suffer most from malnutrition. To provide their family with food they pass on quality food which are essential for their nutrition.[37]

Causes of malnutrition

Most terrain of Bangladesh is low-lying and is prone to flooding. A large population of the country lives in areas that are at risk of experiencing extreme annual flooding that brings large destruction to the crops.[38] Every year, 20% to 30% of Bangladesh is flooded.[39] Floods threaten food security and their effects on agricultural production cause food shortage.[40]

The health and sanitation environment also affects malnutrition. Inadequacies in water supply, hygiene and sanitation have direct impacts on infectious diseases, such as malaria, parasitic diseases, and schistosomiasis. People are exposed to both water scarcity and poor water quality. Groundwater is often found to contain high arsenic concentration.[41] Sanitation coverage in rural areas was only 35% in 1995.[42]

Almost one in three people in Bangladesh defecates in the open among the poorest families. Only 32% of the latrines in rural areas attain the international standards for a sanitary latrine. People are exposed to feces in their environment daily.[43] The immune system falls and the disease processes exacerbate loss of nutrients, which worsens malnutrition.[44] The diseases also contribute through the loss of appetite, lowered absorption of vitamins and nutrients, and loss of nutrients through diarrhoea or vomiting.[45]

Unemployment and job problems also lead to malnutrition in Bangladesh. In 2010, the unemployment rate was 5.1%.[46] People do not have working facilities all year round and they are unable to afford the minimum cost of a nutritious diet due to the unsteady income.[47]

Effects of malnutrition in Bangladesh

Health effects

Undernourished mothers often give birth to infants who will have difficulty with development, pertaining to health problems such as wasting, stunting, underweight, anaemia, night blindness and iodine deficiency.[33] As a result, Bangladesh has a high child mortality rate and is ranked 57 in the under-5 mortality rank.[48]

Economic effects

As 40% of the population in Bangladesh are children,[49] malnutrition and its health effects among children can potentially lead to a lower educational attainment rate. Only 50% of an age group of children in Bangladesh managed to enroll into secondary school education.[48] This would result in a low-skilled and low productivity workforce which would affect the economic growth rate of Bangladesh with only 3% GDP growth in 2009.[48]

Efforts to combat malnutrition

Many programmes and efforts have been implemented to solve the problem of malnutrition in Bangladesh. UNICEF together with the government of Bangladesh and many other NGOs such as Helen Keller International, focus on improving the nutritional access of the population throughout their life-cycle from infants to the child-bearing mother.[33] The impacts of the intervention are significant. Night blindness has reduced from 3.76% to 0.04% and iodine deficiency among school-aged children has decreased from 42.5% to 33.8%.[33]

Maternal and child health status in Bangladesh

Maternal and child health is an important issue in a country like Bangladesh.[50] Bangladesh is one of the developing countries who signed onto achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In the new target of SDGs the issue of maternal and child health is fitting under goal number three. Over the last two decades, national health policy and strategies progressed with significant achievements. Still now Bangladesh is aiming to reduce maternal and child mortality through its renovation process.[51]

Maternal health

The MDG Goal five target was to reduce the maternal mortality rate (MMR) from 574 to 143 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2015 in Bangladesh. There has been a significant downfall in the MMR rates; however, the trajectory is not enough to meet the targets.[50]

The maternal mortality rate (MMR) per 100,000 live births was estimated at 385 globally and 563 in Bangladesh in 1990. In 2015, MMR was 176 per 100,00 live births in Bangladesh and 216 globally. However, the number of deaths of women while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of the pregnancy in Bangladesh were 21,000 in 1990 which reduced dramatically and reached at 5,500 in 2015.[52]

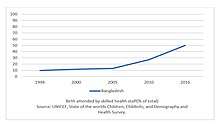

The reduction in maternal mortality is attributed to multiple factors. The factors like improved assess and utilization of health facilities, improvements in female education and per capita income helped to achieve the goal. Fertility reduction have also contributed to reduce MMR by lowering the number of high risk, high parity births. However, the antenatal care (ANC) coverage has been increased between 1990 to 2014. The proportion of women receiving at least one antenatal visit rose from 28% in 1990 to 64% in 2014 from a medically trained provider.[53]

In 2014, the population of women aged 15-49 who received postnatal care within 2 days after giving birth was 36%, antenatal coverage for at least four visits was 31%, proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel was 42%, caesarean section was 23%, proportion of women age 20-24 years old who gave birth before 18 years was 36%, number of women age 15-49 years with a live birth delivery in a health facility was 37% and births who had their first postnatal check-up within the first two days after birth was 31% in Bangladesh.[54]

The major causes of Maternal Mortality are - postpartum haemorrhage (31%), Eclampsia /pre-eclampsia (20%), delayed & obstructed labour (7%), Abortion (1%), other direct cause (5%) and indirect cause (35%).[55] In Bangladesh prevalence of undernourishment among adolescent girls and pregnant women is very high, and one-third of such women have low BMI and anemia. In urban area, anemia and Vitamin A deficiency was found to be prevalent among most of the pregnant mothers.[56]

Child health

To achieve the MDG-4 target, Bangladesh has experienced a significant reduction of child mortality over the past decades. But under 5 mortality must be reduced to achieve the SDG Goal three target. Neonatal mortality is a puissant part of overall child mortality. Neonatal mortality rate of Bangladesh fell gradually from 1990 to 2015.[50] In 1990, per 1000 live births under five mortality rate and infant mortality rate was 93 and 64 globally but in Bangladesh it was higher than the global average. In 2017, global under five mortality rate and infant mortality rate was 39 and 29 per 1000 live births respectively and in Bangladesh this rate was lower than the world average.[57]

| Childhood Mortality Trends in Bangladesh (Deaths per 1000 live births)[57] | |||||||

| Category | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 |

| Under-5 mortality rate | 143.80 | 114.00 | 87.40 | 66.20 | 49.20 | 36.40 | 32.40 |

| Infant mortality rate | 97.70 | 80.90 | 64.00 | 50.40 | 38.90 | 29.80 | 26.90 |

| Neonatal mortality rate | 64.10 | 52.30 | 42.40 | 34.90 | 27.40 | 20.70 | 18.40 |

In 1990, the number of under-5 deaths, infant deaths, and neonatal deaths were 532193.00, 368085.00 and 240316.00 and in 2017 the number reduced and reached at 99608.00, 82240.00 and 56341.00 respectively.[57] The major causes of under-5 child mortality were preterm birth 18%, intrapartum 13.8%, pneumonia 13.5%, sepsis 11%, congenital 9.1%, injury 7.9%, diarrhoea 7.1%, measles 1.9% and other 15.9%.[58]

A study on risk factors of infant mortality, using data from the 2014 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, showed that the risk of mortality in Bangladesh is 1.5 times higher for smaller babies. Infant mortality in Bangladesh is also lower for the urban population as well as for higher economic classes (which have greater access to health services).[59]

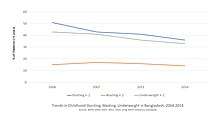

In Bangladesh, just over half of all children were anemic in 2011. A number of interventions have taken to address this issue, including the distribution of iron supplements and deworming tablets every 6 months till 5 years of age. However, children age 6-59 months receive Vitamin-A capsules twice a year. Between 2004 and 2014 the prevalence of children who are stunted, and underweight declined 29% and 23% respectively. But the prevalence of wasting showed very little change during this period.[53]

Maternal and child health care delivery system

In the health system of Bangladesh, maternal and Child Health (MCH) services have been given highest priority. At the society level, MCH services are provided by the Family Welfare Assistants and Health Assistants. A Family Welfare Visitor (FWV) along with a Sub‑Assistant Community Medical Officer or Medical Assistants are responsible for providing the services, at the union level. At Upazila level, Medical officer provides MCH services in Upazila Health Complex. The activities of the Maternal and Child Health unit along with other maternal health care services are overseen by Upazila Health and Family Planning Officer in the Upazila Health Complex. The district hospitals provide maternal services through an outpatient consultation center and a labor ward.[56] However, to provide MCH services private sector is playing supplementary and often competitive role in health sector with public one. NGOs also have a significant role providing primary, reproductive and family planning services.[51]

| Level of care and type of health facility in Bangladesh[56] | ||

| Level of Care | Administrative Unit | Facility |

| Tertiary level | Division or Capital | Teaching Hospital/Institute |

| Secondary level | District | District Hospital |

| Primary level | Upazila

Union Ward |

Upazila Health Complex

Union Health and Family Welfare Centres Community Clinic |

| Source: DGHS, 2010[23] DGHS: Directorate General of Health Services | ||

Development of maternal and child health policy

In following decades, Bangladesh government’s policy concentrated on reduction of population growth; policy perceived that a consistent maternal and child health based family planning programme would help to achieve development goals. The Health and Population Sector Strategy (HPSS) was developed in 1997. The following seven strategies were included in the HPSP (MOHFW, 1998): 1) Focus on Emergency Obstetric Care for reducing maternal mortality, 2) Provision of Essential Obstetric Care/Basic maternity care services for promotion of “good practices” including early detection and appropriate referral of complications 3) Addressing the needs of women through a woman friendly hospital initiative 4) Communication for behaver change and development 5) Involvement of professional bodies 6) Stakeholder participation 7) Promotion of innovation. This policy document is theoretical framework of what is necessary and expected for improvement of maternal health situation in national level and It includes maternal services such as emergency obstetric care, antenatal care, skilled attendance, postnatal care, neonatal care and family planning.[51]

Occupational health

Occupational health deals with all aspects of health and safety in the workplace and has a strong focus on primary prevention of hazards.[60]

Health problems of female workers in RMG sector

Bangladesh has emerged as a key player in RMG (Ready Made Garment) sector since 1978. Textiles and clothing account for about 85% of total export earnings of Bangladesh.[61] Before the starting of RMG sector, woman’s participation in the formal economy has been low compared to man but in late 1980s after orienting this sector, the scenario has dramatically changed and now 80 percent of the total employment in RMG sector is occupied by female worker. But the health of this ‘women-driven sector’ is neglected.

Common health issues

A recent survey-based research study provided a much-needed snapshot data on self-reported chronic health conditions among female garment workers. The following health conditions were reported to be the most prevalent among this population: dysuria; joint pain; hypertension; vision problems; insomnia; asthma; anxiety; gout; diabetes;and heart attack. The fact that a health condition like dysuria (painful or difficult urination) is so highly prevalent among young female garment workers is not surprising.Urinary tract infection, vaginitis, urinary retention, sexually transmitted conditions are related to dysuria. Moreover, also asthma has been reported to be high among garment and textile workers previously (in other countries as well). It is quite likely that a high proportion of garment workers actually develop asthma while working in factories.[62]

Reproductive health problem of workers

Bangladesh has made significant progress in reducing maternal mortality. However, the work environment of RMG has the potential to create health problems, particularly for vulnerable groups such as pregnant women. This paper explores perceptions of health problems during pregnancy of factory workers, in this important industry in Bangladesh. Female workers reported that participation in paid work created an opportunity for them to earn money but pregnancy and the nature of the job, including being pressured to meet the production quota, pressure to leave the job because of their pregnancy and withholding of maternity benefits, cause stress, anxiety and may contribute to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. This was confirmed by factory doctors who suggested that developing hypertensive disorders during pregnancy was influenced by the nature of work and stress. The employers seemed focused on profit and meeting quotas and the health of pregnant workers appeared to be a lower priority. The women reported that they do not visit the factory doctor for an ante-natal check-up when they first suspect that they are pregnant because they feel they need to hide their pregnancy from their supervisors. For example, they needs to meet a production quota of one hundred pieces per hour. If they lag behind the quota due to their pregnancy, their supervisors will encourage them to leave the job. They will also not be assigned to do overtime to earn extra money. They only go to the factory clinic for a check-up during pregnancy when their pregnancy becomes visible. They also do not go to the private clinics because of the cost.[63]

Healthcare for the workers

- BGMEA (Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association) recognizes the fundamental rights of the workers, particularly access to healthcare facilities. On this spirit BGMEA runs 12 Health Centers for the garment workers and their families, provide pre – medical services and medicines at free of cost. •

Training session of female workers in garment sector

Training session of female workers in garment sector - Besides, it run awareness program on HIV/ AIDS, tuberculosis, reproductive health and the use of contraceptive devices.

- In addition to this, BGMEA runs a full-fledged hospital for workers in Chittagong.

- Another hospital for workers is under construction at Mirpur in Dhaka. [64]

- Lastly,every garment factory must have to ensure to place a health clinic with full time doctor and nurse/medical assistance with following facilities and give proper training about health and sanitation specially to pregnant workers to minimize the health issues.

Doctor's room:

- Sickness Analysis

- Medical Issue Register

- Treatment Register

- Medicine Stock Register

- First Aid Training register

- Accident / injury Register

- Maternity Follow up file

- Medical Consolation Graph

- Maintain first aid kit[65]

Neglected tropical diseases of Bangladesh

There is a huge burden of the Neglected Tropical diseases (NTDs) in Bangladesh, particularly for Kala-azar; Lymphatic Filariasis, Dengue and Chikungunya.

Chikungunya

Chikungunya is one of the neglected tropical diseases of Bangladesh. It is a viral disease which is transmitted to humans by infected mosquitoes – including Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus,which is present in Bangladesh.[66] It is an RNA virus that belongs to the alphavirus genus of the family Togaviridae. It was first described during an outbreak in southern Tanzania in 1952.[67]Since then, CHIKV has been reported to cause several large-scale outbreaks in Africa, India, Southeast Asia, Western Pacific and Americas.[68] In the South-East Asia region, Chikungunya virus is maintained in the human population by a human-mosquito-human transmission cycle that differs from the sylvatic transmission cycle on the African continent.[69]

Transmission

Chikungunya is a vector-borne disease transmitted to humans by the bites of infected female mosquitoes which breed in clean water collections in containers, tanks, disposables, junk material in domestic and peri-domestic situations besides natural habitats like tree holes, plantations etc. These mosquitoes can be found biting throughout daylight hours, though there may be peaks of activity in the early morning and late afternoon. A high vector density is seen in the post monsoon season that enhances the transmission.[69]

Signs and symptoms

It causes fever and severe joint pain. Other symptoms include muscle pain, headache, nausea, fatigue and rash. Joint pain is often debilitating and can vary in duration. Chikungunya is rarely fatal. Symptoms are generally self-limiting and last for 2–3 days. The disease shares some clinical signs with dengue and zika, and can be misdiagnosed in areas where they are common.[68]

Here is the Clinical features of Chikungunya virus infections compared with dengue virus infections.[69]

| Findings | Chikungunya | Dengue |

| Fever (>39°C) | +++ | ++ |

| Arthralgia | +++ | +/- |

| Arthritis | + | - |

| Headache | ++ | ++ |

| Rash | ++ | + |

| Myalgia | + | ++ |

| Hemorrhage | +/- | ++ |

| Shock | - | + |

Diagnosis

Several methods can be used for diagnosis. Serological tests, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), may confirm the presence of IgM and IgG anti-chikungunya antibodies. IgM antibody levels are highest 3 to 5 weeks after the onset of illness and persist for about 2 months. Samples collected during the first week after the onset of symptoms should be tested by both serological and virological methods (RT-PCR).[67]

Treatment

There is no vaccine to prevent or anti-viral drugs to treat Chikungunya virus. Treatment is directed primarily at relieving the symptoms, including the joint pain using anti-pyretics, optimal analgesics and fluids.[67]

Outbreaks in Bangladesh:

In Bangladesh, the first recognized outbreak of Chikungunya was reported in 2008 in two villages in the northwest part of the country adjacent to Indian border.[70] Two small-scale outbreaks were documented in rural communities in 2011[70] and 2012.[71]

A massive outbreak of Chikungunya occurred in Bangladesh during the period of April-September, 2017 and over two million people at Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh were at risk of getting infected by the virus.[72] A recent research study (1326 cases) was conducted (between July 24 and August 5, 2017) to investigate the clinical profiles, economic burden, and quality of life of Chikungunya affected individuals.[68] Severe arthropathy is the most consistent clinical feature of chikungunya infection. In this study, all patients experienced Arthalgia(100%); Pain before fever (74.66%); Skin Rash(69.6%); Itching (60.9%); Headache (77.3%) and Myalgia (69.3%) (Figure-2).

Also,t he severity of certain clinical manifestations of Chikungunya might depend on several factors including age, gender, immune status, genetic predisposition and co-morbid conditions.[73] Children (<15 years) tended to have a higher proportion of oligo-arthralgia and skin rash; while morning stiffness, severity, and duration of pain were proportionally lower among children as compared to other age groups. Joint swelling was most commonly noted in elderly patients (60+ years), while the severity of pain was highest among adults (30–59 years).[68]Chikungunya infection caused significant loss of productivity due to absenteeism from job, household work and school.

Prevention and control

Prevention is entirely dependent upon taking steps to avoid mosquito bites and elimination of mosquito breeding sites.[74]

To avoid mosquito bites

Wear full sleeve clothes and long dresses to cover the limbs. Use mosquito coils, repellents and electric vapour mats during the daytime.Use mosquito nets – to protect babies, old people and others, who may rest during the day. The effectiveness of such nets can be improved by treating them with permethrin (pyrethroid insecticide). Mosquitoes become infected when they bite people who are sick with Chikungunya. Mosquito nets and mosquito coils will effectively prevent mosquitoes from biting sick people.

To prevent mosquito breeding

The Aedes mosquitoes that transmit Chikungunya breed in a wide variety of man-made containers which are common around human dwellings. These containers collect rainwater, and include discarded tires, flowerpots, old oil drums, animal water troughs, water storage vessels, and plastic food containers. These breeding sites can be eliminated by Draining water from coolers, tanks, barrels, drums and buckets, etc. Emptying coolers when not in use. Removing from the house all objects, e.g. plant saucers, etc. which have water collected in them.

Chikungunya epidemics, with the high attack rate of CHIKV, affect a large number of people in a short period of time associated with early rain fall (early monsoon) and this is also consistently seen in Bangladesh outbreak 2017. Pain, the most frequent clinical manifestation of Chikungunya, is difficult to control, compromising the quality of life, intense psychosocial and economic repercussions, causing a serious public health problem that requires a targeted approach.[75] General physicians, Infectious disease specialists, Rheumatologist and other specialist, nurses, pain specialists, physiotherapists, social workers, and healthcare managers are required to overcome these challenges so that an explosive increase in CHIKV cases can be mitigated.

See also

References

- Shah, Jahangir (18 April 2011). দারিদ্র্য কমেছে, আয় বেড়েছে [Reduced poverty, increased income]. Prothom Alo (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- "Health Bulletin 2015". Management Information System, Directorate General of Health Services, Mohakhali, Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh. December 2015.

- Nargis, M. "Scaling-up Innovations, Community Clinic in Bangladesh". Additional Secretary & Project Director, Revitalization of Community Health Care Initiatives in Bangladesh (RCHCIB), MoHFW.

- "World Bank Data". World Bank. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- বরাদ্দ বেড়েছে স্বাস্থ্য খাতে [The allocation has increased in the health sector]. Jugantor (in Bengali). Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "Hospital Beds (Per 10,000 Population), 2005–2011". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- Syed Masud Ahmed; Md Awlad Hossain; Ahmed Mushtaque Raja Chowdhury & Abbas Uddin Bhuiya (2011), "The health workforce crisis in Bangladesh: shortage, inappropriate skill-mix and inequitable distribution", Human Resources for Health, 9 (3): 3, doi:10.1186/1478-4491-9-3, PMC 3037300, PMID 21255446

- National Institute of Population Research and Training Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Dhaka, Bangladesh. "Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014" (PDF). dhsprogram.com. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- "Country Profile". World Bank. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- "Indicators". World Bank. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- Hossain, Shah Monir. Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) in Bangladesh, An overview. Former Director General of Health Services Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Senior Consultant, PPC, MOHFW Senior Advisor, Eminence. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- "Country profiles: For 30 high TB burden countries" (PDF). Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Tuberculosis Control In Bangladesh, Annual Report 2018, Page (1,2,6)" (PDF). Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "21. Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) in Bangladesh". icddr,b. Evidence to Policy Series Brief No.2. May 2010.

- Omran, AR (9 November 2005). ". The Epidemiologic Transition: A Theory of the Epidemiology of Population Change". The Milbank Quarterly. 83 (4): 731–757. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00398.x. PMC 2690264. PMID 16279965.

- 13. Global report on diabetes, 1. Diabetes Mellitus – epidemiology. 2. Diabetes Mellitus – prevention and control. 3. Diabetes, Gestational. 4. Chronic Disease. 5. Public Health. I. World Health Organization. 2016. ISBN 978-92-4-156525-7.

- IDF Diabetes Atlas. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation.

- Hussain, A (2007). "Type 2 diabetes and impaired fasting blood glucose in rural Bangladesh: a population based study". European Journal of Public Health. 17 (3): 291–6. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckl235. PMID 17008328.

- Rahim, AM (June 2002). Diabetes in Bangladesh: Prevalence and determinant (Master of Philosophy in International Community Health). University of Oslo.

- Lim, SS (December 2012). "A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 380(9859):2224–60. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. PMC 4156511. PMID 23245609.

- Rahim, MA (August 2007). "Rising prevalence of type 2 diabetes in rural Bangladesh: A population based study". Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 77 (2): 300–5. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2006.11.010. PMID 17187890.

- Hussain, A (July 2005). "Type 2 diabetes in rural and urban population: diverse prevalence and associated risk factors in Bangladesh". Diabet. Med.: 22(7):931–6.

- Sayeed, MA (2003). "Diabetes and impaired fasting glycemia in a rural population of Bangladesh". Diabetes Care. 26 (4): 1034–9. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.4.1034. PMID 12663569.

- Sayeed, MA (1997). "Effect of socioeconomic risk factors on the difference in prevalence of diabetes between rural and urban population of Bangladesh". Diabetes Care. 20: 551-5. (4): 551–555. doi:10.2337/diacare.20.4.551. PMID 9096979.

- Sayeed, MA (1997). "Prevalence of diabetes in a suburban population of Bangladesh". Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 34: 149-55.

- Nag, KD (October–December 2015). "Diabetic retinopathy at presentation to screening service in Bangladesh". Bangladesh Ophthalmic Journal. 01 (4): 26–29.

- Wong, TY (March 2006). "Diabetic retinopathy in a multi-ethnic cohort in the United States". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 141 (3): 446–455. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.063. PMC 2246042. PMID 16490489.

- Wong, TY (November 2008). "Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy: the Singapore Malay Eye Study". Ophthalmology. 115 (11): 1869–75. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.05.014. PMID 18584872.

- "Bangladesh Healthcare Crisis". BBC News. 28 February 2000. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- Heitzman, James; Worden, Robert, eds. (1989). "Health". Bangladesh: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 90.

- "Fighting Malnutrition in Bangladesh". World Bank in Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- "Children and women suffer severe malnutrition". IRIN. 19 November 2008. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- "Child and Maternal Nutrition in Bangladesh" (PDF). UNICEF.

- "The state of food insecurity in the food 2011" (PDF). FAO.

- "The State of the World's Children 2011" (PDF). UNICEF.

- "High Malnutrition in Bangladesh prevents children from becoming "Tigers"". Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014.

- Rizvi, Najma (22 March 2013). "Enduring misery". D+C Development and Cooperation. Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development.

- "Rural poverty in Bangladesh". Rural Poverty Portal. International Fund for Agricultural Development.

- "Bangladesh: Priorities for Agriculture and Rural Development". World Bank. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008.

- "Poverty Profile People's Republic of Bangladesh Executive Summary" (PDF). Japan International Cooperation Agency. October 2007.

- "Bangladesh's Water Crisis". Water.org.

- Hadi, Abdullaheil (September 2000). "A participatory approach to sanitation: experience of Bangladeshi NGOs" (PDF). Health Policy and Planning. 15 (3): 332–337. doi:10.1093/heapol/15.3.332. PMID 11012409. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2012.

- "Rural Sanitation, Hygiene and Water Supply" (PDF). UNICEF.

- "C. Nutrition and Infectious Disease Control". Supplement to SCN News No. 7 (Mid-1991). United Nations. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011.

- "Underlying Causes of Malnutrition". Mother and Child Nutrition. The Mother and Child Health and Education Trust.

- Islam, S. M. Raisul. "Unemployment Problem in Bangladesh". academia.edu.

- "Nutrition Program". Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- "Bangladesh – Statistics". UNICEF.

- "Bangladesh, Effects of the Financial Crisis on Vulnerable Households" (PDF). WFP.

- Rajia, Sultana; Sabiruzzaman, Md.; Islam, Md. Kamrul; Hossain, Md. Golam; Lestrel, Pete E. (15 March 2019). Uthman, Olalekan (ed.). "Trends and future of maternal and child health in Bangladesh". PLOS ONE. 14 (3): e0211875. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1411875R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0211875. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6420003. PMID 30875380.

- Khan, Nur Newaz (28 November 2017). "Maternal and child health in Bangladesh: a critical look at the policy and the sustainable development goals". Asian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 3 (3): 298–304. doi:10.3329/ajmbr.v3i3.34517. ISSN 2412-5571.

- "WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2015". Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Success Factors for Women's and Children's Health, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Bangladesh. Page(12,14)" (PDF). Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "UNICEF, Bangladesh, Maternal and Newborn Health". Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Maternal mortality affects development of a country". The Daily Star. 2 October 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Mahmudur Rahman, A. H. M. (2018). "A review on child and maternal health status of bangladesh". CHRISMED Journal of Health and Research. 5 (1): 1. doi:10.4103/cjhr.cjhr_65_17. ISSN 2348-3334.

- "UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation, Bangladesh". Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "UNICEF, Under five mortality, Cause of death". Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Vijay, Jyoti; Patel, Kamalesh Kumar (24 July 2019). "Risk factors of infant mortality in Bangladesh". Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health. doi:10.1016/j.cegh.2019.07.003. ISSN 2213-3984.

- "Occupational health". WHO.

- "Compliance System of Apparel/Garment Industry In Bangladesh". Textile Learner.

- "Health issues of RMG workers need attention". The Daily Star. 3 April 2019.

- Akhter, Sadika; Rutherford, Shannon; Chu, Cordia (2017). "What makes pregnant workers sick: why, when, where and how? An exploratory study in the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh". Reproductive Health. 14 (1). doi:10.1186/s12978-017-0396-0.

- "BGMEA'S Activities". Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association.

- "Buyer Compliance Checklist in Apparel Industry". Apparel Costing.

- "WHO | Chikungunya". WHO. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- "World Health Organization, Chikungunya: a mosquito-borne disease". SEARO. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Raheem, Enayetur; Mosabbir, Abdullah Al; Aziz, KM Sultanul; Hossain, Md Akram; Asna, Shah Md Zahurul Haque; Dipta, Tashmim Farhana; Khan, Zohora Jameela; Khaleque, Md Abdul; Arafat, S. M. Yasir (6 June 2018). "Chikungunya outbreak (2017) in Bangladesh: Clinical profile, economic impact and quality of life during the acute phase of the disease". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 12 (6): e0006561. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006561. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 6025877. PMID 29874242.

- "National Guideline on Clinical Management of Chikungunya Fever" (PDF).

- Khatun, Selina; Chakraborty, Apurba; Rahman, Mahmudur; Nasreen Banu, Nuzhat; Rahman, Mohammad Mostafizur; Hasan, S. M. Murshid; Luby, Stephen P.; Gurley, Emily S. (2015). "An Outbreak of Chikungunya in Rural Bangladesh, 2011". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 9 (7): e0003907. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003907. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 4498910. PMID 26161995.

- Salje, Henrik; Lessler, Justin; Paul, Kishor Kumar; Azman, Andrew S.; Rahman, M. Waliur; Rahman, Mahmudur; Cummings, Derek; Gurley, Emily S.; Cauchemez, Simon (22 November 2016). "How social structures, space, and behaviors shape the spread of infectious diseases using chikungunya as a case study". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (47): 13420–13425. doi:10.1073/pnas.1611391113. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 5127331. PMID 27821727.

- Hosen, Mohammad Jakir; Vanakker, Olivier M.; Ullah, Mohammad Ohid; Khan, Fahim; Mourosi, Jarin Taslem; Anwar, Saeed (15 May 2019). "Chikungunya Outbreak in Bangladesh (2017): Clinical and hematological findings". bioRxiv: 639872. doi:10.1101/639872.

- Teng, Terk-Shin; Kam, Yiu-Wing; Lee, Bernett; Hapuarachchi, Hapuarachchige Chanditha; Wimal, Abeyewickreme; Ng, Lee-Ching; Ng, Lisa F. P. (15 June 2015). "A Systematic Meta-analysis of Immune Signatures in Patients With Acute Chikungunya Virus Infection". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 211 (12): 1925–1935. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv049. ISSN 1537-6613. PMC 4442625. PMID 25635123.

- "World Health Organization, Chikungunya". SEARO. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- "Chikungunya". ResearchGate. Retrieved 18 September 2019.