Education in Bangladesh

Education in Bangladesh is overseen by the Bangladesh's Ministry of Education. Ministry of Primary and Mass Education are responsible for implementing policy for primary education and state-funded schools at a local level. In Bangladesh, all citizens must undertake twelve years of compulsory education which consists of eight years at primary school level and four years at high school level. Primary and secondary education is financed by the state and free of charge in public schools.

| |

| Ministry of Education Ministry of Primary and Mass Education | |

|---|---|

| Minister for Education Minister for Primary and Mass Education | Dipu Moni Mostafizur Rahman (politician) |

| National education budget (2015) | |

| Budget | US$2.185 billion (172.951 billion Taka)[1] |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | Bengali, English |

| System type | National |

| Established Compulsory Education | 4 November 1972 |

| Literacy (2017[2]) | |

| Total | 72.89% |

| Male | 75.69% |

| Female | 70.09% |

| Enrollment | |

| Total | 23,907,151 |

| Primary | 16,230,000 |

| Secondary | 7,400,000 |

| Post secondary | 277,151 |

| Attainment | |

| Secondary diploma | 335,454 |

| Post-secondary diploma | 86,948 |

| "Bangladesh Education Stats". NationMaster. Retrieved 12 September 2016. "Statistical Pocket Book-2006" (PDF). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2016. | |

Bangladesh conforms fully to the UN's Education For All (EFA) objectives[3] and the Millennium Development Goals (MDG)[4] as well as other education-related international declarations. Article 17 of the Bangladesh Constitution provides that all children receive free and compulsory education.[5]

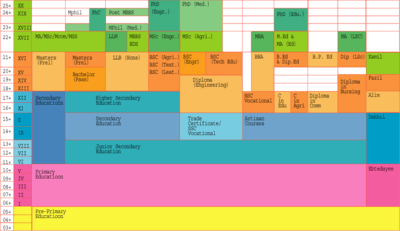

Education system

The main education system is divided into three levels:

- Primary Level (Class 1–8)[6]

- Secondary Level (9-12) There is no middle school system in Bangladesh.[7]

- Tertiary Level

At all levels of schooling, students can choose to receive their education in English or Bangla. Private schools tend to make use of English-based study media while government-sponsored schools use Bangla.

Cadet Colleges are important in the education system of Bangladesh. A cadet college is a room and board collegiate administered by the Bangladesh Military. Discipline is compulsory at all cadet colleges. Faujdarhat Cadet College is the first cadet college in Bangladesh, established in 1958 over an area of 185 acres (0.75 km2) at Faujdarhat in the district of Chittagong. At present there are 12 cadet colleges in Bangladesh, including 3 cadet colleges for girls.

As of September 2019, tertiary education in Bangladesh takes place at 44 government, 101 private and 3 international universities. Students can choose to further their studies in Chartered Accountancy, engineering, technology, agriculture and medicine at a variety of universities and colleges.

Table: Number of Primary Education Institution, Teacher and Student, 2018

| School type | No. of School | Total Teachers | Total Students | ||||

| Total | Female | % of Female | Total | Girls | % of Girls | ||

| Govt. Primary School | 38033 | 222652 | 144434 | 64.9 | 10188129 | 5252022 | 51.6 |

| New Nationalized PS | 25008 | 96460 | 47396 | 49.1 | 4483785 | 2278239 | 50.8 |

| Total government school | 63041 | 319112 | 191830 | 60.11 | 14671914 | 7530261 | 51.32 |

| Regd. NGPS | 193 | 771 | 464 | 60.2 | 38282 | 19611 | 51.2 |

| Non-regd. NGPS | 1744 | 6649 | 4716 | 70.9 | 256268 | 127112 | 49.6 |

| School for Autistic | 33 | 282 | 246 | 89.2 | 10652 | 5250 | 49.3 |

| Ebtadaee Madrasah | 2673 | 11673 | 2300 | 19.7 | 372277 | 181341 | 48.7 |

| Kindergarten | 16170 | 93799 | 54813 | 58.4 | 1988365 | 914016 | 46.0 |

| NGO School | 2512 | 5454 | 3764 | 69.0 | 210170 | 107898 | 51.3 |

| Community School | 120 | 405 | 322 | 79.5 | 16747 | 8679 | 51.8 |

| Attached to High Madrasah | 5526 | 19764 | 2812 | 14.2 | 871047 | 427341 | 49.1 |

| Primary Sections of High School | 1511 | 8301 | 4450 | 53.6 | 572751 | 295659 | 51.6 |

| BRAC | 7779 | 7798 | 7277 | 93.3 | 324438 | 185873 | 57.3 |

| ROSC School | 3818 | 3591 | 2867 | 79.8 | 106884 | 53751 | 50.3 |

| Sishu Kollyan Primary School | 133 | 410 | 277 | 67.6 | 15665 | 8284 | 52.9 |

| Other Schools | 3262 | 4875 | 2967 | 60.9 | 97519 | 48808 | 50.0 |

| Grand Total: | 108515 | 482884 | 279105 | 57.8 | 19552979 | 9913884 | 50.7 |

| Non English Medium School | 108515 |

| English Medium School | 196 |

Primary education The overall responsibility of management of primary education lies with the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MOPME), set up as a Ministry in 1992. While MOPME is involved in formulation of policies, the responsibility of implementation rests with the Directorate of Primary Education (DPE) headed by a Director General. The Directorate of Primary Education (DPE) and its subordinate offices in the district and upazila are solely responsible for management and supervision of primary education. Their responsibilities include recruitment, posting, and transfer of teachers and other staff; arranging in-service training of teachers; distribution of free textbooks; and supervision of schools. The responsibility of school construction, repair and supply of school furniture lies with the DPE executed through the Local Government Engineering Department (LGED). The National Curriculum and Textbook Board (NCTB) is responsible for the development of curriculum and production of textbooks. While the Ministry of Education (MOE) is responsible for formulation of policies, the Directorate of Secondary and Higher Education (DSHE) under the Ministry of Education is responsible for implementing the same at secondary and higher education levels. The NCTB is responsible for developing curriculum and publishing standard textbooks.

The Directorate of Primary Education (DPE) are responsible for conducting the two public examinations:

- Primary Education Certificate (PEC) (5 grade)

- Junior School Certificate (JSC) (8th grade)

Secondary education

The secondary level of education is controlled by the eight General Education boards:

- Barisal Education Board for Barisal Division

- Chittagong Education Board for Chittagong Division

- Comilla Education Board for Comilla Division

- Dhaka Education Board for Dhaka Division

- Dinajpur Education Board for Rangpur Division

- Jessore Education Board for Khulna Division

- Mymensingh Education Board for Mymensingh Division

- Rajshahi Education Board for Rajshahi Division

- Sylhet Education Board for Sylhet Division

The boards' headquarters are located in Barishal, Comilla Chittagong, Dhaka, Dinajpur Jessore, Mymensingh, Rajshahi and Sylhet.

Eight region-based Boards of Intermediate and Secondary Education (BISE) are responsible for conducting the two public examinations:

- Secondary School Certificate (SSC) (10th grade)

- Higher Secondary School Certificate (HSC) (12th grade)

At the school level, in the case of non-government secondary schools, School Management Committees (SMC), and at the intermediate college level, in the case of non-government colleges, Governing Bodies (GB), formed as per government directives, are responsible for mobilizing resources, approving budgets, controlling expenditures, and appointing and disciplining staff. While teachers of non-government secondary schools are recruited by concerned SMCs observing relevant government rules, teachers of government secondary schools are recruited centrally by the DSHE through a competitive examination.

In government secondary schools, there is not an SMC. The headmaster is solely responsible for running the school and is supervised by the deputy director of the respective zone. Parent Teachers Associations (PTAs), however, exist to ensure a better teaching and learning environment.

Tertiary education

%2C_Islamic_University_of_Technology.jpg)

At the tertiary level, universities are regulated by the University Grants Commission. The colleges providing tertiary education are under the National University. Each of the medical colleges is affiliated with a public university. Universities in Bangladesh are autonomous bodies administered by statutory bodies such as Syndicate, Senate, Academic Council, etc. in accordance with provisions laid down in their respective acts.[8][9]

Technical and vocational education

The Technical and Vocational Education System provides courses related to various applied and practical areas of science, technology and engineering, or focuses on a specific specialized area. Course duration ranges from one month to four years. The Technical Education Board controls technical and vocational training in the secondary level.

The Directorate of Technical Education (DTE) is responsible for the planning, development, and implementation of technical and vocational education in the country. Curriculum is implemented by BTEB. In the Technical Education System, after obtaining a Diploma-in-Engineering degree (four-year curriculum) from the institutes listed below, students can further pursue their educational career by obtaining a bachelor's degree from Engineering & Technology Universities. It normally it takes an additional two and a half to three years of coursework to obtain a bachelor's degree, although some students take more than three years to do so. They can then enroll in post-graduate studies. Students can also study CA (Chartered Accounting) after passing HSC or bachelor's degree and subject to fulfilling the entry criteria of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Bangladesh (ICAB).

- BCMC College of Engineering & Technology - ISO certified & the largest private engineering college in Bangladesh, situated in Jessore.

- Graphic Arts Institute - the only Government Printing & Graphic Design Institute in Bangladesh

- Comilla Polytechnic Institute- It's founded in 1962. It is one of the largest and well-reputed government polytechnic institute.

- Barisal Polytechnic Institute – one of the largest polytechnic Institutes in Bangladesh

- Patuakhali Polytechnic Institute - It is one of the largest Polytechnic Institutes in Bangladesh

- Bogra Polytechnic Institute – It is one of the largest Polytechnic institutes in Bangladesh

- Chittagong Polytechnic Institute – provides theoretical and practical education of basic Engineering and technology

- Jessore Polytechnic Institute

- Dhaka Polytechnic Institute – a government technical institute in Dhaka

- Feni Polytechnic Institute – created on 29 February 1964, the institute has around 2,000 students

- Khulna Polytechnic Institute – a government technical institute in Khulna

- Kushtia Polytechnic Institute – The largest polytechnic institute in Bangladesh

- Mymensingh Polytechnic Institute – established in 1963 by the Ford Foundation

- Rajshahi Polytechnic Institute – a government technical institute in Rajshahi.

- Sylhet Polytechnic Institute – a state-supported technical academic institute, it was established in 1955 by the Pakistani Government

- Mangrove Institute of Science and Technology – a non-government technical institute in Khulna

Alternative education system

English language schools

English-medium schools are mainly private schools where all the courses are taught in English except one Bengali Language subject at ordinary level (O Level). These schools in Bangladesh follow the General Certificate of Education (GCE) syllabus where students are prepared for taking their Ordinary Level (O Level) and Advanced Level (A Level) examinations. The General Certificate of Education system is one of the most internationally recognized qualifications, based in the United Kingdom. The Ordinary and Advanced Level examinations are English equivalent to the Secondary School Certificate (SSC) and Higher Secondary School Certificate (HSC) examinations respectively. Most students sit for these exams from the registered schools in Bangladesh who follow the GCE syllabus. Those who do not attend a school that follows the GCE syllabus may also sit for their Ordinary and Advanced Level examinations from the British Council. These examinations are conducted under the supervision of the British Council in Bangladesh. The GCE examination conducted by the British Council takes place twice a year. Currently there are two boards operating from Bangladesh for Ordinary and Advanced Level Examinations, which are Edexcel and University of Cambridge International Examinations. Bangladesh has recently opened English version schools translating board textbooks in English. In recent years national language policy has given top priority to English language education in Bangladesh [10]

Madrasah education

The Madrasah Education System focuses on religious education, teaching all the basics of education in a religious environment. Religious studies are taught in Arabic and the students in some areas also serve the local area masjids. Students also have to complete all the courses from the General Education System. Many privately licensed Madrasas take in homeless children and provide them with food, shelter and education, e.g. Jamia Tawakkulia Renga Madrasah in Sylhet. In the Madrasah Education System there are two systems:

One, called the "Quomi" Madrasah system is privately owned and funded[11] and is run according to the Deobandi system of Islamic education, which rejects the rational sciences.[12]

The other, called the "Alia" madrasah system, is privately owned but subsidised by the government (the government spends 11.5% of its education budget on alia madrasahs, paying 80% of teacher and administrator salaries).[11] Quomi madrasahs account for 1.9% of total primary enrollment and 2.2% of secondary enrollment; aliyah madrasahs account for 8.4% of primary and 19% of secondary enrollment.[13] The alia system is like the general education system, except that Arabic is taught in addition to general education. The Madrasah Education Board covers religious education in government-registered Madrasahs in the secondary level. After passing "Alim", a student can enroll for 3 additional years to obtain a "Fazil" level. Students can go for further general education and earn a university degree. After passing successfully, they can further enroll for another 2 years to obtain a "Kamil" level degree.

The following table provides a statistical comparison of the "Quomi" and "Alia" madrasah systems.[14]

| Profile of madrassa education in Bangladesh | |

|---|---|

| Number of private (Quomi) madrassas | 13,902 |

| Number of government-funded (Alia) madrassa | 6,906 |

| Number of teachers in Quomi madrassas | 130,000 |

| Number of teachers in Alia madrassas | 100,732 |

| Number of students in Quomi madrassas | 1,462,500 |

| Number of students in Alia madrassas | 1,878,300 |

| Total number of madrassas (Quomi + Alia) | 13,406 |

| Total number of teachers (Quomi + Alia) | 230,732 |

| Total number of students (Quomi + Alia) | 3,340,800 |

Refugee education

As of 2020, approximately one-third of refugee Rohingya children were able to access primary education, primarily through temporary centers run by international organizations. UNICEF runs approximately 1,600 learning centers across the country, educating around 145,000 children.[15] Beginning in April 2020, UNICEF and the Government of Bangladesh will enroll 10,000 Rohingya children in schools where they will be taught the Myanmar school curriculum.[15]

Grading system in Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, grades equal or above 33% (or one third) is considered as a passing grade. Although by no means it is considered as a good grade. Since the education system of Bangladesh is completely controlled by the government up to higher secondary level (or grade 12), the grading system up to this point is more or less the same. For each subject, grades are converted in to grade points (GP) and are summed up and dived by the total number of subjects and thus is called Grade Point Average (GPA). The highest achievable GPA is 5.0. There is also a term called Letter Grade (LG) that indicates a range of GPA for total result or a single GP for a single subject. The grading system is shown below.

| Class interval | Grade Point | Letter Grade |

|---|---|---|

| 100-80 | 5 | A+ |

| 79 -70 | 4 | A |

| 69 - 60 | 3.5 | A- |

| 59 - 50 | 3 | B |

| 49 -40 | 2 | C |

| 39 - 33 | 1 | D |

| 32 - 0 | 0 | F |

However, in Secondary and Higher Secondary Level, a 4th subject or optional subject system is introduced. Although failing in the 4th subject will not be judged as a failure for the whole, Doing good in it can contribute to gain additional grade points. The additional grade points received is simply (GP in 4th subject) - 2. While counting GPA the algorithm can be simply written as

Here, TGP is the total Grade EPoints gained in subjects other than optional. OGP is the additional GP gained in 4th subject. And N is the number of total subjects of course without optional.

Note that GPA cannot be above 5. and Additional GP gained from the optional subject will not be counted if the GP of the subject is less than or equal to 2. Gaining a GPA of 5.0 or A+ is naturally considered as a good result. However, since a student can gain grade far above the required 80% to receive a GPA of 5.0, the actual grades received in each subject is also included in the official mark sheets given by the education board for PSC, SSC and HSC exams. There is also an unofficial term called Golden A+ which means receiving A+ in all subjects, since a student can receive a perfect GPA also without gaining more than 80% marks in all subjects thanks to the 4th subject system.

Non-formal education

There exists a substantial number of NGO-run non-formal schools, catering mainly to the drop-outs of the government and non-government primary schools. Very few NGOs, however, impart education for the full five-year primary education cycle. Because of this, on completion of their two-to-three-year non-formal primary education in NGO-run schools, students normally re-enter into government/non-government primary schools at higher classes.

There are Non-Governmental Schools (NGO) and Non-Formal Education Centers (NFE) and many of these are funded by the government. The largest NFE program is the much reputed BRAC program. However, not all NFE graduates continue on to secondary school.

NGO-run schools differ from other non-government private schools. While the private schools operate like private enterprises often guided by commercial interests, NGO schools operate mainly in areas not served either by the government or private schools, essentially to meet the educational needs of vulnerable groups in the society. They usually follow an informal approach to suit the special needs of children from these vulnerable groups. But nowadays, some NGO schools are operating into places where there are both private and government schools.

Similarly, in NGO-run schools there does not exist any SMC. The style of management differs depending upon differences in policies pursued by different NGOs. Some are centrally managed within a highly bureaucratic set-up, while others enjoy considerable autonomy.

Different NGOs pursue different policies regarding recruitment of teachers. Some prepare a panel of prospective teachers on the basis of a rigorous test and recruit teachers from this panel. Other NGOs recruit teachers rather informally from locally available interested persons.

Current Issues

Current government projects to promote the education of children in Bangladesh include compulsory primary education for all, free education for girls up to grade 10, stipends for female students, a nationwide integrated education system and a food-for-education literacy movement. A large section of the country's national budget is set aside to help put these programs into action and to promote education and make it more accessible. Recent years have seen these efforts pay off and the Bangladesh education system is strides ahead of what it was only a few years ago. Now even national curriculum books from class 5 to class 12 are distributed freely among all students and schools.

The educational system of Bangladesh faces several problems. In the past, Bangladesh education was primarily a British modelled upper class affair with all courses given in English and very little being done for the common people. The Bangladesh education board has taken steps to leave such practices in the past and is looking forward to education as a way to provide a poverty-stricken nation with a brighter future. As Bangladesh is an overpopulated country, there is a huge demand to turn its population into labour, which is why proper education is needed and proper help from government in the educational sectors of Bangladesh is crucial.

Education expenditure as percentage of GDP

Public expenditure on education lies on the fringes of 2 percent of GDP with a minimum of 0.94 percent in 1980 and a maximum of 2.2 percent in 2007.[16]

Qualitative dimension

The Education system lacks a sound Human Resource Development and deployment system[17] and this has demoralised the primary education sector personnel, including teachers, and contributes to poor performance. Poverty is a big threat to primary education. In Bangladesh, the population is very high. The number of seats available in colleges is less than the number of students who want to enroll, and the number of seats available in universities is also less than the number of students who passed higher secondary level and want to join in a university. Besides, the cost of education is increasing day by day, as a result many students are unable to afford it.

One study found a 15.5% primary school teacher absence rate.[18]

Gender disparity

In Bangladesh, gender discrimination in education occurs amongst the rural households but is non-existent amongst rich households.[19][20] There is great difference in the success rates of boys, as compared to girls in Bangladesh. However, in recent years some progress has been made in trying to fix this problem.[21]

School attendance

The low performance in primary education is also matter of concern. School drop-out rates and grade repetition rates are high.[22] Poor school attendance and low contact time in school are factors contributing to low level of learning achievement.

Religion and education

Madrasah education in Bangladesh is heavily influenced by religion.[23]

Literacy rate

Bangladesh has one of the lowest literacy rates in Asia, estimated at 66.5% for males and 63.1% for females in 2014. Recently the literacy rate of Bangladesh has improved as it stands at 71% as of 2015 due to the modernization of schools and education funds.[24]

See also

References

- Bin Habib, Wasim and Adhikary, Tuhin Shubhra (31 May 2016). Education budget in Bangladesh too inadequate. asianews.network.

- "Bangladesh education". UNESCO.

- Bangladesh: Education for All 2015 National Review. Ministry of Primary and Mass Education, Government of Bangladesh. unesco.org.

- Millennium Development Goals: Bangladesh Progress Report 2015. General Economics Division (GED), Bangladesh Planning Commission. plancomm.gov.bd.

- "The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh: Article 17 (Free and compulsory education)". Legislative and Parliamentary Affairs Division, Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- "Primary education now up to class VIII". The Daily Star. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "Primary education up to class VIII, secondary XII". The Daily Star. 25 August 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "Private University". Banglapedia. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- "University Grants Commission". Banglapedia. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- https://rdcu.be/bFJXM

- Ahmad, Mumtaz (2007). "Islam, state, and society in Bangladesh". In Esposito, John; Voll, John; Bakar, Osman (eds.). Asian Islam in the 21st Century. Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-804421-5.

- Tan, Charlene, ed. (2014). Reforms in Islamic Education: International Perspectives. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-4411-0134-1.

- Alam, Mahmadul; A.T.M Shaifullah Mehedi; Nehraz Mahmud (2013). "Religious education in Bangladesh". In Davis, Derek; Miroshnikova, Elena (eds.). The Routledge International Handbook of Religious Education. New York: Routledge. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-136-25641-7.

- Ahmad, Mumtaz (2004). "Madrassa Education in Pakistan and Bangladesh" (PDF). In Limaye, Satu P.; Wirsing, Robert C.; Malik, Mohan (eds.). Religious radicalism and security in South Asia. Honolulu: Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-234-28935-5.

- Aziz, Saba; Mahmud, Faisal (30 January 2020). "'Great news': Bangladesh allows education for Rohingya children". Al Jazeera English.

- Education Spending, Bangladesh, at theglobaleconomy.com Accessed 26 April 2017

- Sedere, Upali M. (2000). "Institutional Capacity Building Through Human Resource Development". Directorate of Primary Education/PEDPQI Project of NORAD, Bangladesh.

- "Roll Call: Teacher Absence in Bangladesh" (PDF). Site resources.world bank.org. 2004. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Huq, Molla; Rahman, Pk Md. Motiur (May 2008). "Gender Disparities in Secondary Education in Bangladesh" (PDF). International Education Studies. 1 (2). Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- Abu S. SHONCHOY* and Mehnaz RABBANI: The Bangladesh Gender Gap in Education: Biased Intra-household Educational Expenditures, at ide.go.jp Archived 23 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 26 April 2017

- Niels-Hugo Blunch, Maitreyi Bordia Das: Changing norms about gender inequality in education: Evidence from Bangladesh Accessed 1 May 2017

- "Country Profiles: Bangladesh". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "The Impact of Islamic Schools in Bangladeshi Society: The Case of Madrassa". alochonaa.com. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- "Bangladesh's literacy rate rises to 70 percent, education minister says". bdnews24. 16 June 2015.

Further reading

- Rosser, Yvette Claire (2004). Indoctrinating Minds: Politics of Education in Bangladesh. New Delhi: Rupa & Co. ISBN 8129104318.

- Rosser, Yvette Claire (2003). Curriculum as Destiny: Forging National Identity in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh (PDF) (Dissertation). University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- Sedere, Upali M. (2000). "Institutional Capacity Building Through Human Resource Development". Directorate of Primary Education/PEDPQI Project of NORAD, Bangladesh.

- Sedere, Upali M. (1996). "General Education Project (CR2118BD) Report". World Bank.

- Literacy In Bangladesh

- Information Literacy: Bangladesh perspective

- Information Literacy: A challenge for Bangladesh

- Female Secondary School Assistance Project: Bangladesh

- Literacy and Adult Education

- The Girls' Stipend Program in Bangladesh

- Country Report 2006 Bangladesh

- Bangladesh Education Sector Overview

- UNESCO Information and Monitoring Sheet

- UNESCO Survey

- UNICEF Statistics

- Bangladesh, pre-primary education and the school learning improvement plan: promising EFA practices in the Asia-Pacific region; case study

- Education for All 2015 National Review

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Education in Bangladesh. |