Health in Indonesia

Health in Indonesia is affected by air quality, disease, poverty and smoking.

29% of the population of Indonesia are under 15 years old, and only 5% are over 65. Life expectancy at birth is 70.8 years. It has been suggested that over a third of the children under 5 have stunted growth. More than 28 million live below the poverty line of US$17 a month and about half the population have incomes not much above it. The rate of smoking is the highest in the world - 76%[1] and about 400,000 die each year from smoking related illnesses.[2]

Life expectancy

| Period | Life expectancy in Years |

Period | Life expectancy in Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–1955 | 43.5 | 1985–1990 | 62.4 |

| 1955–1960 | 47.0 | 1990–1995 | 64.2 |

| 1960–1965 | 50.2 | 1995–2000 | 65.8 |

| 1965–1970 | 53.1 | 2000–2005 | 66.7 |

| 1970–1975 | 55.9 | 2005–2010 | 67.7 |

| 1975–1980 | 58.5 | 2010–2015 | 68.6 |

| 1980–1985 | 60.7 |

Source: United Nations[3]

Water quality

Unsafe drinking water is a major cause of diarrhoea, which is a major killer of young children in Indonesia.[4] According to UNICEF diarrhoea caused by untreated drinking water contributed to the death of 31% of children between the age of 1 month to a year, and 25% of children between a year to 4 years old.[5]

Disease

HIV/AIDS has posed a major public health threat since the early 1990s.[4] In 2003 Indonesia ranked third among ASEAN nations in Southeast Asia, after Myanmar and Thailand, with a 0.1 percent adult prevalence rate, 130,000 HIV/AIDS cases, and 2,400 deaths.[4] In Jakarta it is estimated that 17 percent of prostitutes have contracted HIV/AIDS; in some parts of Papua, it is thought that the rate of infection among village women who are not prostitutes may be as high as 26 percent.[4]

Three other health hazards facing Indonesia in 2004 were dengue fever, dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) and avian influenza.[4] All 30 provincial-level units were affected by dengue fever and DHF, according to the WHO. The outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (A/H5N1) in chickens and ducks in Indonesia was said to pose a significant threat to human health.[4]

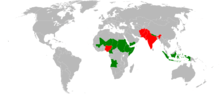

By 2010, there were three malaria regions in Indonesia: Nusa Tenggara Barat with 20 cases per 1,000 citizens, Nusa Tenggara Timur with 20-50, and Maluku and Papua with more than 50 cases per thousand. The medium endemicity in Sumatra, Kalimantan and Sulawesi, whereas low endemicity is in Java and Bali which almost 100 percent of malaria cases have been confirmed clear.[6] At 1990 malaria average incidence was 4.96 per 1,000 and declined to 1.96 per 1000 at 2010. The government is targeting to rid the country of malaria by 2030 and elimination means to achieve less than 1 incidence per 1,000 people.[7]

Diabetes is increasing at a rate of about 6% a year.[8]

Air quality

1997 Southeast Asian haze, 2006 Southeast Asian haze, 2013 Southeast Asian haze and 2015 Southeast Asian haze - In all countries affected by the smoke haze, an increase of acute health outcomes was observed. Health effects including emergency room visits due to respiratory symptoms such as asthma, upper respiratory infection, decreased lung function as well as eye and skin irritation, were caused mainly by this particulate matter.

Vaccination

Indonesia has routine vaccination to children below age 5 years as World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations including vaccination of Hepatitis B which has high prevalency in Indonesia. All of the vaccines used in National Immunization Program provided by Bio Farma, local vaccine manufacturer.[9]

In June 2011, the third phase test of dengue vaccine involving 800 humans with ages of 2 and 14 years old have been held in 5 community health centre around Jakarta and will be conducted also in Bandung, West Java and Denpasar, Bali with 800 and 400 participants, respectively. The first test was performed on a limited number of soldiers and the second phase was conducted on a small number of children and if within the next 5 years the vaccine is found to be safe for humans, government will apply the dengue vaccine to public.[10]

Maternal and child health care

The 2010 maternal mortality rate per 100,000 births for Indonesia is 240. This is compared with 228.6 in 2008 and 252.9 in 1990. The under 5 mortality rate, per 1,000 births is 41 and the neonatal mortality as a percentage of under 5's mortality is 49. In Indonesia the number of midwives per 1,000 live births is unavailable and the lifetime risk of death for pregnant women is 1 in 190.[11]

The 2012 maternal mortality rate per 100,000 live births is 359 deaths, a significant increased from 2010 data with 220 deaths and far from the MDGs goal of 102 deaths by the end of 2015. The main cause of deaths are severe post-natal bleeding due to lack of pregnancy regular control, although National Family Planning Coordination Board and the Central Statistics Agency data showed improvement from 93 percent of women received prenatal care in 2007 increased to 96 percent in 2012.[12]

See also

References

- Ballas, Dimitris; Dorling, Danny; Hennig, Benjamin (2017). The Human Atlas of Europe. Bristol: Policy Press. p. 77. ISBN 9781447313540.

- Britnell, Mark (2015). In Search of the Perfect Health System. London: Palgrave. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-137-49661-4.

- "World Population Prospects - Population Division - United Nations". Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- Indonesia country profile. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (December 2004). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "IssueBriefs: Water, sanitation & hygiene" (PDF). UNICEF Indonesia. October 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- Leksono, Ageng Wibowo (23 April 2011). "Malignant malaria still haunts Indonesia". Antara. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- "Govt to rid RI of malaria by 2030". The Jakarta Post. 26 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011.

- Britnell, Mark (2015). In Search of the Perfect Health System. London: Palgrave. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-137-49661-4.

- "Negara Menjamin Ketersediaan dan Keamanan Vaksin Untuk ORI dan Imunisasi Rutin". Biro Komunikasi dan Pelayanan Masyarakat, Kementerian Kesehatan RI. 13 January 2018.

- Aditya, Andreas D. (8 June 2011). "Jakarta begins testing new dengue vaccine". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011.

- "The State Of The World's Midwifery". United Nations Population Fund. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Gokkon, Basten (29 January 2014). "Indonesia Still Haunted by High Number of Maternal and Post-Natal Deaths". Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014.

External links

- The State of the World's Midwifery - Indonesia Country Profile