Desomorphine

Desomorphine[note 1] is a semi-synthetic opioid commercialized by Roche, with powerful, fast-acting effects, such as sedation and analgesia.[3][4][5][6] It was first discovered and patented by a German team working for Knoll in 1920[7] but wasn't generally recognized. It was later synthesized in 1932 by Lyndon Frederick Small. Small also successfully patented it in 1934 in the United States.[8] Desomorphine was used in Switzerland under the brand name Permonid[9] and was described as having a fast onset and a short duration of action, with relatively little nausea compared to equivalent doses of morphine. Dose-by-dose it is eight to ten times more potent than morphine.[10]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Permonid |

| Other names | Desomorphine, krokodil, dihydrodesoxymorphine, Permonid |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.406 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H21NO2 |

| Molar mass | 271.360 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

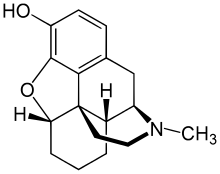

Desomorphine is a morphine analogue where the 6-hydroxyl group and the 7,8 double bond have been reduced.[8] The traditional synthesis of desomorphine starts from α-chlorocodide, which is itself obtained by treating thionyl chloride with codeine or prescription opioid pain medicines such as OxyContin and Vicodin. By catalytic reduction, α-chlorocodide gives dihydrodesoxycodeine, which yields desomorphine on demethylation.[11][12]

Uses

Medical

Desomorphine was previously used in Switzerland and Russia for the treatment of severe pain; although for many years up to 1981, when its use was terminated, it was being used to treat a single person in Bern, Switzerland with a rare illness.[13] While desomorphine was found to be faster acting and more effective than morphine for the rapid relief of severe pain, its shorter duration of action and the relatively more severe respiratory depression produced at equianalgesic doses, as well as a high incidence of other side effects such as hypotension and urinary retention, were felt to outweigh any potential advantages.[14][15]

Recreational

Desomorphine abuse in Russia attracted international attention in 2010 due to an increase in clandestine production, presumably due to its relatively simple synthesis from codeine available over the counter. Abuse of homemade desomorphine was first reported in Siberia in 2003 when Russia started a major crackdown on heroin production and trafficking, but has since spread throughout Russia and the neighboring former Soviet republics.[13]

The drug can be made from codeine and iodine derived from over-the-counter medications and red phosphorus from match strikers,[16] in a process similar to the manufacturing of methamphetamine from pseudoephedrine. Like methamphetamine, desomorphine made this way is often contaminated with various agents. The street name in Russia for homemade desomorphine is krokodil (Russian: крокодил, crocodile), possibly related to the chemical name of the precursor α-chlorocodide, or the resemblance of the skin damage caused by the drug to a crocodile's leather.[13] Due to difficulties in procuring heroin, combined with easy and cheap access to over-the-counter pharmacy products containing codeine in Russia, use of krokodil increased until 2012.[17] In 2012 the Russian federal government introduced new restrictions for the sale of codeine-containing medications. This policy change likely diminished, but did not extinguish krokodil use in Russia.[18] It has been estimated that around 100,000 people use krokodil in Russia and around 20,000 in Ukraine.[17] One death in Poland in December 2011 was also believed to have been caused by krokodil use, and its use has been confirmed among Russian expatriate communities in a number of other European countries.[19] In 2013 two cases of Krokodil use were reported in the United States.[20] A single case of desomorphine use was reported in Spain in 2014, with the drug consumed orally rather than by injection.[21] In 2019, there was a case of desomorphine abuse in the UK with a 41-year-old shoplifter and drug addict becoming victim to severe skin damage as a result of abusing 'krokodil'.[22]

Adverse effects

Toxicity

Toxicity of desomorphine

Animal studies comparing pure desomorphine to morphine showed it to have increased toxicity, more potent relief of pain, higher levels of sedation, decreased respiration, and increased digestive activity.[23]

Toxicity of "krokodil"

Illicitly produced desomorphine is typically far from pure and often contains large amounts of toxic substances and contaminants as a result of being "cooked" and used without any significant effort to remove the byproducts and leftovers from synthesis. Injecting any such mixture can cause serious damage to the skin, blood vessels, bone and muscles, sometimes requiring limb amputation in long-term users.[10]

Causes of this damage are from iodine, phosphorus and other toxic substances that are present after synthesis. Addicts often use readily available but relatively toxic and impure solvents such as battery acid, gasoline or paint thinner during the reaction scheme, without adequately removing them afterwards before injection. Strong acids and bases such as hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide are also employed without measuring pH of the final solution and analysis of leftover solutions of "krokodil" in used syringes showed the pH was typically less than 3 (i.e. as acidic as lemon juice). Failure to remove insoluble fillers and binding aids from the codeine tablets used as starting material, as well as co-administration with pharmaceuticals such as tropicamide and tianeptine, are also cited as possible contributors to the high toxicity observed in users.

The frequent occurrence of tissue damage and infection among illicit users are what gained the drug its nickname of the flesh-eating drug, or the zombie drug as homemade versions made under inadequate conditions contain multiple impurities and toxic substances that lead to severe tissue damage and subsequent infection as a direct consequence of use. Gangrene, phlebitis, thrombosis (blood clots), pneumonia, meningitis, septicaemia (blood infection), osteomyelitis (bone infection), liver and kidney damage, brain damage, and HIV/AIDS are common serious adverse health effects observed among users of krokodil.[17] Sometimes, the user will miss the vein when injecting the desomorphine, creating an abscess and causing death of the flesh surrounding the entry-point.[10]

Reinforcement disorders

Early medical trials of humans taking desomorphine have resulted in the finding that, like morphine and most other analgesics of the morphine type, small amounts are highly addictive and tolerance to the drug develops quickly. However, though tolerance to respiratory depression with repeated doses was observed in rats, early clinical trials failed to show any tolerance to these same effects with repeated doses in humans.[23]

Chemistry

Desomorphine has a molecular weight of 271.35 g/mol and three salts are known: hydrobromide (as in the original Permonid brand; free-base conversion ratio 0.770), hydrochloride (0.881) and sulfate (0.802).[24] Its freebase form is slightly soluble in water (1.425 g/L at 25 °C), although its salts are very water-soluble; its freebase form is also very soluble in most polar organic solvents (like acetone, ethanol and ethyl acetate).[10] Its melting point is 189 °C.[10] It has a pKa of 9.69.[10] Desomorphine comes in four isoforms, A, B, C, and D[25] and the latter two appear to be the more researched and used.

Krokodil is made from codeine mixed with other substances. The codeine is retrieved from over-the-counter medicine and is then mixed with ethanol, gasoline, red phosphorus, iodine, hydrochloric acid and paint thinner.[10][26] Toxic nitrogen oxide fumes emerge from the drug when heated.[27]

History

Desomorphine was first synthesised in the U.S. in 1932 and patented on 13 November 1934.[13] In Russia, desomorphine was declared an illegal narcotic analgesic in 1998. However, while codeine-containing drugs generally have been prescription products in Europe, in Russia they were sold freely over-the-counter until June 2012.[28] The number of users in Russia was estimated to have reached around one million at the peak of the drug's popularity.[29]

Society and culture

Legal status

In the US, desomorphine is a Schedule 1 controlled substance, indicating that the United States FDA has determined that there are no legal medicinal uses for desomorphine in the U.S. It has maintained this status as a controlled substance in the United States since 1936.[23] The drug is a Narcotic in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act 1970 of the United States as drug number (ACSCN) 9055. It is therefore subject to annual aggregate manufacturing quotas in the United States, and in 2014 the quota for desomorphine was 5 grams.[30] It is produced as a hydrochloride (free base conversion ratio 0.85) and sulphate (0.80).[31]

North American media

The media in the U.S. and Canada have brought awareness to desomorphine. There have been incidents reported where desomorphine had supposedly been present within either country,[32] but no incidents have been confirmed by any drug-testing or analytical results, and desomorphine use in North America is still considered unconfirmed.[33][34]

Notes

References

- Shuster, Simon (5 December 2013). "The World's Deadliest Drug: Inside a Krokodil Cookhouse". Time.

- Christensen, Jen (18 October 2013). "Flesh-eating 'zombie' drug 'kills you from the inside out'". CNN.

- Casy AF, Parfitt RT (1986). Opioid analgesics: chemistry and receptors. New York: Plenum Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-306-42130-3.

- Bognar R, Makleit S (June 1958). "Neue Methode für die Vorbereitung von dihydro-6-desoxymorphine" [New method for the preparation of dihydro-6-desoxymorphine]. Arzneimittel-Forschung (in German). 8 (6): 323–5. PMID 13546093.

- Janssen PA (April 1962). "A Review of the Chemical Features Associated with Strong Morphine-Like Activity". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 34 (4): 260–8. doi:10.1093/bja/34.4.260. PMID 14451235.

- Sargent LJ, May EL (November 1970). "Agonists--antagonists derived from desomorphine and metopon". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (6): 1061–3. doi:10.1021/jm00300a009. PMID 4098039.

- DE Patent 414598C 'Verfahren zur Herstellung von Dihydrodesoxymorphin und Dihydrodesoxycodein'

- US patent 1980972, Lyndon Frederick Small, "Morphine Derivative and Processes", published 1934-19-07, issued 1934-13-11

- "Krokodil". New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- Katselou M, Papoutsis I, Nikolaou P, Spiliopoulou C, Athanaselis S (May 2014). "A "krokodil" emerges from the murky waters of addiction. Abuse trends of an old drug". Life Sciences. 102 (2): 81–7. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2014.03.008. PMID 24650492.

- Mosettig E, Cohen FL, Small LF (1932). "Desoxycodeine Studies. III. The Constitution of the So-Called α-Dihydrodesoxycodeine: Bis-Dihydrodesoxycodeine". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 54 (2): 793–801. doi:10.1021/ja01341a051.

- Eddy NB, Howes HA (1935). "Studies of Morphine, Codeine and their Derivatives X. Desoxymorphine-C, Desoxycodeine-C and their Hydrogenated Derivatives". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 55 (3): 257–67.

- Gahr M, Freudenmann RW, Hiemke C, Gunst IM, Connemann BJ, Schönfeldt-Lecuona C (2012). "Desomorphine goes "crocodile"". Journal of Addictive Diseases. 31 (4): 407–12. doi:10.1080/10550887.2012.735570. PMID 23244560.

- Eddy NB, Halbach H, Braenden OJ (1957). "Synthetic Substances with Morphine-like Effect: Clinical Experience: Potency, Side-Effects, Addiction Liability". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. Monographs on Individual Drugs: Desomorphine. 17 (4–5): 569–863. PMC 2537678. PMID 13511135.

- Matiuk DM. Krokodil: A Monstrous Drug with Deadly Consequences. Journal of Addictive Disorders 2014; 1-14. Retrieved 17 April 2017 from Breining Institute at http://www.breining.edu

- Savchuk SA, Barsegyan SS, Barsegyan IB, Kolesov GM (2011). "Chromatographic study of expert and biological samples containing desomorphine". Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 63 (4): 361–70. doi:10.1134/S1061934808040096.

- Grund JP, Latypov A, Harris M (July 2013). "Breaking worse: the emergence of krokodil and excessive injuries among people who inject drugs in Eurasia". The International Journal on Drug Policy. 24 (4): 265–74. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.04.007. PMID 23726898.

- Zheluk A, Quinn C, Meylakhs P (September 2014). "Internet search and krokodil in the Russian Federation: an infoveillance study". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 16 (9): e212. doi:10.2196/jmir.3203. PMC 4180331. PMID 25236385.

- Skowronek R, Celiński R, Chowaniec C (April 2012). ""Crocodile"--new dangerous designer drug of abuse from the East". Clinical Toxicology. 50 (4): 269. doi:10.3109/15563650.2012.660574. PMID 22385107.

- https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/09/26/heroin-krokodil-flesh-rotting-arrives-us-arizona/2879817/

- Baquero Escribano A, Beltrán Negre MT, Calvo Orenga G, Carratalá Monfort S, Arnau Peiró F, Meca Zapatero S, Haro Cortés G (June 2016). "Orally ingestion of krokodil in Spain: report of a case". Adicciones. 28 (4): 242–245. doi:10.20882/adicciones.828. PMID 27391849.

- Gogarty, Conor (5 February 2019). "'Horrific' health problems of 'flesh-eating zombie drug' user". gloucestershirelive. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- "DESOMORPHINE (Dihydrodesoxymorphine; dihydrodesoxymorphine-D; Street Name: Krokodil, Crocodil" (PDF). Drug Enforcement Administration. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- "Permonid". PubChem Compound. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- Ganellin C, Triggle DJ (21 November 1996). Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents. ISBN 9780412466304.

- Alves EA, Grund JP, Afonso CM, Netto AD, Carvalho F, Dinis-Oliveira RJ (April 2015). "The harmful chemistry behind krokodil (desomorphine) synthesis and mechanisms of toxicity". Forensic Science International. 249: 207–13. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.02.001. PMID 25710781.

- "Desomorphine". Specialized Information Services. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Берсенева А. (23 June 2011). "Без рецепта не обезболят". Gazeta.ru. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- "Krokodil". New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- "DEA Diversion Control Division".

- "DEA Diversion Control Division".

- Haskin A, Kim N, Aguh C (March 2016). "A new drug with a nasty bite: A case of krokodil-induced skin necrosis in an intravenous drug user". JAAD Case Reports. 2 (2): 174–6. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.02.007. PMC 4864092. PMID 27222881.

- No Confirmed Reports of Desomorphine ( "Krokodil" / "Crocodile" ) in Canada (PDF). Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. 21 November 2013. ISBN 978-1-77178-052-0.

- Mullins ME, Schwarz ES (July 2014). "'Krokodil' in the United States is an urban legend and not a medical fact". The American Journal of Medicine. 127 (7): e25. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.040. PMID 24970607.

External links