Acting president of the United States

An acting president of the United States is an individual who legitimately exercises the powers and duties of the president of the United States even though that person does not hold the office in their own right. There is an established order in which officials of the United States federal government may be called upon to take on presidential responsibilities if the incumbent president becomes incapacitated, dies, resigns, is removed from office (by impeachment by the House of Representatives and subsequent conviction by the Senate) during their four-year term of office; or if a president-elect has not been chosen before Inauguration Day or has failed to qualify by that date.

Presidential succession is referred to multiple times in the U.S. Constitution – Article II, Section 1, Clause 6, as well as the Twentieth Amendment and Twenty-fifth Amendment. The vice president is the only officeholder named in the Constitution as a presidential successor. The Article II succession clause authorizes Congress to designate which federal officeholders would accede to the presidency in the event that the vice president were unable to do so, a situation which has never occurred. The current Presidential Succession Act was adopted in 1947 and last revised in 2006. The order of succession is as follows: the vice president, the speaker of the House of Representatives, the president pro tempore of the Senate, and then the eligible heads of the federal executive departments who form the president's Cabinet, beginning with the secretary of state.

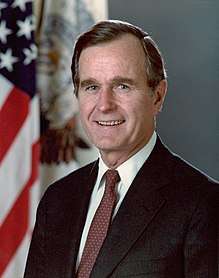

If the president dies, resigns or is removed from office, the vice president automatically becomes president. Likewise, were a president-elect to die during the transition period, or decline to serve, the vice president-elect would become president on Inauguration Day. A vice president can also become the acting president if the president becomes incapacitated. However, should the presidency and vice presidency both become vacant, the statutory successor called upon would not become president, but would only be acting as president. To date, two vice presidents—George H. W. Bush (once) and Dick Cheney (twice)—have been acting president. No one lower in the line of succession has yet been called upon to act as president.

Constitutional provisions

Regarding eligibility

The qualifications for acting president are the same as those for the office of president. Article II, Section 1, Clause 5 prescribes three eligibility requirements for the presidency. At the time of taking office, one must be a natural-born citizen of the United States, at least thirty-five years old, and a resident of the United States for at least fourteen years.[1]

A person who meets these requirements may still be constitutionally disqualified from the presidency under any of the following conditions:

- Article I, Section 3, Clause 7, gives the U.S. Senate the option of disqualifying individuals convicted in impeachment cases from holding federal office in the future.[2]

- Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits any person who swore an oath to support the Constitution, and later rebelled against the United States, from becoming president. However, this disqualification can be lifted by a two-thirds vote of each house of Congress.[3]

- The Twenty-second Amendment prohibits anyone from being elected to the presidency more than twice (or once, if the person serves as president or acting president for more than two years of a presidential term to which someone else was originally elected).[4][5]

Regarding succession

Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 makes the vice president first in the line of succession. It also empowers Congress to provide by law who would act as president in the case where neither the president nor the vice president were able to serve.[6]

Two constitutional amendments elaborate on the subject of presidential succession and fill gaps exposed over time in the original provision:

- Section 3 of the Twentieth Amendment declares that if the president-elect dies before his term begins, the vice president-elect becomes president on Inauguration Day and serves for the full term to which the president-elect was elected, and also that, if on Inauguration Day, a president has not been chosen or the president-elect does not qualify for the presidency, the vice president-elect acts as president until a president is chosen or the president-elect qualifies. It also authorizes Congress to provide for instances in which neither a president-elect nor a vice president-elect have qualified.[7] Acting on this authority, Congress incorporated "failure to qualify" as a possible condition for presidential succession into the Presidential Succession Act of 1947.[8]

- Sections 3 and 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment provide for situations in which the president is temporarily or indefinitely unable to discharge the powers and duties of the office.[9]

History

Before the Twenty-fifth Amendment

On April 4, 1841, only one month after his inauguration, William Henry Harrison died. He was the first U.S. president to die in office.[10] Afterward, a constitutional crisis ensued over the Constitution's ambiguous presidential succession provision (Article II, Section 1, Clause 6).[11]

Shortly after Harrison's death, his Cabinet met and decided that John Tyler, Harrison's vice president, would assume the responsibilities of the presidency under the title "Vice-President acting President".[12] Instead of accepting this proposed title, however, Tyler asserted that the Constitution gave him full and unqualified powers of the presidency and had himself sworn in as president; this set a critical precedent for the orderly transfer of power following a president's death.[13] Nonetheless, several members of Congress, such as representative and former president John Quincy Adams, felt that Tyler should be a caretaker under the title of "acting president", or remain vice president in name.[14] Senator Henry Clay saw Tyler as the "vice-president" and his presidency as a mere "regency".[15]

Throughout Tyler remained resolute in his claim to the title of President and in his determination to exercise the full powers of the presidency. The precedent he set in 1841 was followed subsequently on seven occasions when an incumbent president died prior to being enshrined in the Constitution through section 1 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment.[11]

Though the precedent regarding presidential succession due to the president's death was set, questions concerning presidential "inability" remained unanswered. What constituted an inability? Who determined the existence of an inability? Did a vice president become president for the rest of the presidential term in the case of an inability, or was the vice president merely "acting as president"? Due to this lack of clarity, later vice presidents were hesitant to assert any role in cases of presidential inability.[16]

On two occasions, in particular, the operations of the executive branch were hampered due to the fact that there was no constitutional basis for declaring that the president was unable to function:

- For 80 days in 1881, between the shooting of James Garfield in July and his death in September.[17] Congressional leaders urged Vice President Chester Arthur to step-up and exercise presidential authority while the president was disabled, but he declined, fearful of being labeled a usurper. Aware that he was in a delicate position and that his every action was placed under scrutiny, he remained secluded in his New York City home for most of the summer.[18]

- October 1919 – March 1921, when Woodrow Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke. Nearly blind and partially paralyzed, he spent the final 17 months of his presidency sequestered in the White House.[19] Vice President Thomas Marshall, the cabinet, and the nation were kept in the dark over the severity of the president's illness for several months. Marshall was pointedly afraid to ask about Wilson's health, or to preside over cabinet meetings, fearful that he would be accused of "longing for his place."[20]

Since the Twenty-fifth Amendment

Proposed by the 89th Congress and subsequently ratified by the states in 1967, the Twenty-fifth Amendment also established formal procedures for addressing instances of presidential disability and succession.[21] Its Section 3, which allows the president to voluntarily transfer his authority to the vice president, has been invoked on three occasions by two presidents. (Section 4, which addresses the case of an incapacitated president who is unable or unwilling to issue voluntary declaration, has not been activated since the amendment came into force.)[17][22]

| Name | Party | Date (time) and reason | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

George H. W. Bush | Republican | July 13, 1985 (11:28 am – 7:22 pm): Vice President George H. W. Bush was acting president while President Ronald Reagan underwent colon cancer surgery under anesthesia.[23][24] | |

|

Dick Cheney | Republican | June 29, 2002 (7:09 am – 9:24 am): Vice President Dick Cheney was acting president while President George W. Bush underwent a colonoscopy under sedation.[25] | |

| July 21, 2007 (7:16 am – 9:21 am): Vice President Dick Cheney was acting president while President George W. Bush underwent a colonoscopy under sedation.[26] | ||||

See also

References

- "Article II. The Executive Branch, Annenberg Classroom". The Interactive Constitution. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The National Constitution Center. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Article I". US Legal System. USLegal. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Moreno, Paul. "Articles on Amendment XIV: Disqualification for Rebellion". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Peabody, Bruce G.; Gant, Scott E. (February 1999). "The Twice and Future President: Constitutional Interstices and the Twenty-Second Amendment". Minnesota Law Review. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Law School. 83 (3): 565–635. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- Albert, Richard (Winter 2005). "The Evolving Vice Presidency". Temple Law Review. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University of the Commonwealth System of Higher Education. 78 (4): 812–893.

- Feerick, John. "Essays on Article II: Presidential Succession". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- Larson, Edward J.; Shesol, Jeff. "The Twentieth Amendment". The Interactive Constitution. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The National Constitution Center. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- "The Continuity of the Presidency: The Second Report of the Continuity of Government Commission" (PDF). Preserving Our Institutions. Washington, D.C.: Continuity of Government Commission. June 2009. p. 31. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 23, 2012 – via WebCite.

- Kalt, Brian C.; Pozen, David. "The Twenty-fifth Amendment". The Interactive Constitution. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The National Constitution Center. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- Freehling, William. "William Harrison: Life In Brief". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center, University of Virginia. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "A controversial President who established presidential succession". Constitution Daily. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: National Constitution Center. March 29, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Dinnerstein, Leonard (October 1962). "The Accession of John Tyler to the Presidency". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 70 (4): 447. JSTOR 4246893.

- Freehling, William. "John Tyler: Life In Brief". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center, University of Virginia. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Chitwood, Oliver Perry (1964) [Orig. 1939, Appleton-Century]. John Tyler, Champion of the Old South. Russell & Russell. pp. 203–207. OCLC 424864.

- Seager, Robert, II (1963). And Tyler Too: A Biography of John and Julia Gardiner Tyler. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 142, 151. OCLC 424866.

- Feerick, John. "Essays on Amendment XXV: Presidential Succession". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- Feerick, John D. (2011). "Presidential Succession and Inability: Before and After the Twenty-Fifth Amendment". Fordham Law Review. 79 (3): 928–932. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- Feerick, John D.; Freund, Paul A. (1965). From Failing Hands: the Story of Presidential Succession. New York City: Fordham University Press. pp. 118–127. LCCN 65-14917.

- Amber, Saladin. "Woodrow Wilson: Life After The Presidency". Charllotesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- "Thomas R. Marshall, 28th Vice President (1913–1921)". Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress 1774 – Present. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- "Presidential Succession". US Law. Mountain View, California: Justia. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Neale, Thomas H. (November 5, 2018). Presidential Disability Under the Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Constitutional Provisions and Perspectives for Congress (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- Boyd, Gerald M. (July 14, 1985). "Reagan Transfers Power to Bush for 8-Hour Period of 'Incapacity'". The New York Times. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Maugh II, Thomas H. (July 27, 1985). "Reagan's Surgery for Colon Cancer Breaks a Taboo, Brings a Floodtide of Calls". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- O'Donnell, Norah (June 29, 2002). "President George W. Bush's Historic Transfer of Power". News report, NBC Nightly News. New York, New York: NBC Universal. Retrieved December 15, 2018 – via NBCLearn.

- Pelofsky, Jeremy (July 23, 2007). "No cancer found after Bush colon exam". Reuters. Retrieved July 20, 2018.