Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope

Rendered model of the WFIRST spacecraft, July 2018 | |

| Names | Joint Dark Energy Mission |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Infrared Space observatory |

| Operator | NASA / JPL / GSFC |

| Website |

wfirst |

| Mission duration | 5 years (planned)[1] |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Launch mass | 4,166 kg (9,184 lb)[2] |

| Dry mass | 4,059 kg (8,949 lb)[2] |

| Payload mass | 2,191 kg (4,830 lb)[2] |

| Power | 2500 watts |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | Mid-2020s |

| Rocket | Delta IV Heavy (proposed)[2] |

| Contractor | United Launch Alliance (proposed) |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Sun–Earth L2 |

| Regime | Halo orbit |

| Periapsis | 188,420 km (117,080 mi) |

| Apoapsis | 806,756 km (501,295 mi) |

| Main telescope | |

| Type | Three-mirror anastigmat |

| Diameter | 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in) |

| Wavelengths | Near-infrared, visible light |

| Transponders | |

| Band |

S band (TT&C support) Ka band (data acquisition) |

| Bandwidth |

Few kbit/s duplex (S band) 290 Mbit/s (Ka band) |

| Instruments | |

|

Coronagraph Instrument Wide Field Instrument | |

The Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) is a NASA infrared space observatory currently under development. WFIRST was recommended in 2010 by United States National Research Council Decadal Survey committee as the top priority for the next decade of astronomy. On February 17, 2016, WFIRST was approved for development and launch.[3]

WFIRST is based on an existing 2.4 m wide field-of-view telescope and will carry two scientific instruments. The Wide-Field Instrument is a 288-megapixel multi-band near-infrared camera, providing a sharpness of images comparable to that achieved by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) over a 0.28 square degree field of view, 100 times larger than that of the HST. The Coronagraphic Instrument is a high-contrast, small field-of-view camera and spectrometer covering visible and near-infrared wavelengths using novel starlight-suppression technology.

The design of WFIRST is based on one of the proposed designs for the Joint Dark Energy Mission between NASA and DOE. WFIRST adds some extra capabilities to the original JDEM proposal, including a search for extra-solar planets using gravitational microlensing.[4] In its present incarnation (2015),[5] a large fraction of its primary mission will be focused on probing the expansion history of the Universe and the growth of cosmic structure with multiple methods in overlapping redshift ranges, with the goal of precisely measuring the effects of dark energy,[6] the consistency of general relativity, and the curvature of spacetime.

On February 12, 2018, development on the WFIRST mission was proposed to be terminated in the President's FY19 budget request, due to a reduction in the overall NASA astrophysics budget and higher priorities elsewhere in the agency.[7][8][9] In March 2018 Congress approved funding to continue making progress on WFIRST until at least September 30, 2018,[10] in a bill stating that Congress "rejects the cancellation of scientific priorities recommended by the National Academy of Sciences decadal survey process".[11] In testimony before Congress in July 2018, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine proposed slowing down the development of WFIRST in order to accommodate a cost increase in the James Webb Space Telescope, which would result in decreased funding for WFIRST in 2020/2021.[12]

Overview

The original design of WFIRST (Design Reference Mission 1), studied in 2011–2012, featured a 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) diameter unobstructed three-mirror anastigmat telescope.[13] It contained a single instrument, a visible to near-infrared imager/slitless prism spectrometer. In 2012, another possibility emerged: NASA could use a second-hand National Reconnaissance Office telescope made by Harris Corporation to accomplish a mission like the one planned for WFIRST. NRO offered to donate two telescopes, the same size as the Hubble Space Telescope but with a shorter focal length and hence a wider field of view.[14] This provided important political momentum to the project, even though the telescope represents only a modest fraction of the cost of the mission and the boundary conditions from the NRO design may push the total cost over that of a fresh design. This mission concept, called WFIRST-AFTA (Astrophysics Focused Telescope Assets), was matured by a scientific and technical team;[15] this mission is now the only present NASA plan for the use of the NRO telescopes.[16] The WFIRST baseline design includes a coronagraph to enable the direct imaging of exoplanets.[17]

WFIRST has had a number of different implementations studied (including the Joint Dark Energy Mission-Omega configuration, an Interim Design Reference Mission featuring a 1.3m telescope,[18] Design Reference Mission 1[19] with a 1.3m telescope, Design Reference Mission 2,[20] with a 1.1m telescope, and several iterations of the AFTA 2.4m configuration). In the most recent report,[5] WFIRST was considered for both geosynchronous and L2 orbits. Appendix C documents the disadvantage of L2 vs. geosynchronous in the data rate and propellant, but the advantages for improved observing constraints, better thermal stability, and more benign radiation environment at L2. Some science cases (such as exoplanet microlensing parallax) are improved at L2, and the possibility of robotic servicing at either of the locations requires further study.

The project is led by a team at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. The Project Scientist for WFIRST from its inception until his death in 2017 was Neil Gehrels, who was succeeded by Jeffrey Kruk; the Project Manager is Kevin Grady; the Program Scientist is Dominic Benford; the Program Executive is John Gagosian; the Formulation Science Working Group is chaired by Gehrels with Deputy Chairs David Spergel and Jeremy Kasdin.[21]

Science objectives

The science objectives of WFIRST aim to address cutting-edge questions in cosmology and exoplanet research, including:

- Answering basic questions about dark energy, complementary to the ESA EUCLID mission, and including: Is cosmic acceleration caused by a new energy component or by the breakdown of general relativity on cosmological scales? If the cause is a new energy component, is its energy density constant in space and time, or has it evolved over the history of the universe? WFIRST will use three independent techniques to probe dark energy: baryon acoustic oscillations, observations of distant supernovae, weak gravitational lensing.

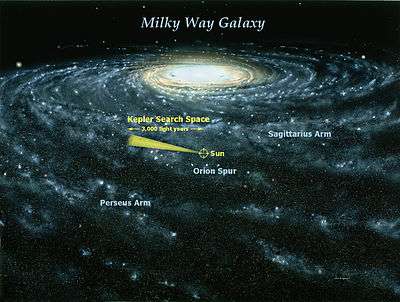

- Completing a census of exoplanets to help answer new questions about the potential for life in the universe: How common are solar systems like our own? What kinds of planets exist in the cold, outer regions of planetary systems? – What determines the habitability of Earth-like worlds? This census makes use of a technique that can find exoplanets down to a mass only a few times that of the Moon: gravitational microlensing.

- Establishing a guest investigator mode, enabling survey investigations to answer diverse questions about our galaxy and the universe.

- Providing a coronagraph for exoplanet direct imaging that will provide the first direct images and spectra of planets around our nearest neighbors similar to our own giant planets.

WFIRST will have two instruments. The Wide-Field Instrument (WFI) is a 288-megapixel camera with a 0.28 square degree field of view providing multi-band near-infrared (0.7 to 2.0 micrometers) imaging using a HgCdTe focal-plane array with a pixel size of 110 milliarcseconds. The detector array will be composed of H4RG-10 detectors provided by Teledyne[22]. It includes a grism for wide-field slitless spectroscopy and an integral field spectrograph for small-field spectroscopy. The second instrument is a high contrast coronagraph covering shorter wavelengths (0.4 to 1.0 micrometers) using novel starlight-suppression technology. It is intended to achieve a part-per-billion suppression of starlight to enable the detection of planets only 0.1 arcseconds away from their host stars.

Funding history and status

In fiscal year 2014, Congress provided $56 million for WFIRST, and in 2015 Congress provided $50 million.[23] The fiscal year 2016 spending bill provided $90 million for WFIRST, far above NASA's request of $14 million, allowing the mission to enter the "formulation phase" in February 2016.[23] On February 18, 2016, NASA announced that WFIRST had formally become a project (as opposed to a study), meaning that the agency intends to carry out the mission as baselined;[3] at that time, the "AFTA" portion of the name was dropped as only that approach is being pursued. WFIRST is on a plan for a mid-2020s launch. The total cost of WFIRST is expected at more than $2 billion;[24] NASA's 2015 budget estimate was around $2.0 billion in 2010 dollars, which corresponds to around $2.7 billion in real year (inflation-adjusted) dollars.[25] In April 2017, NASA commissioned an independent review of the project to ensure that the mission scope and cost were understood and aligned. [26] The review acknowledged that WFIRST offers "groundbreaking and unprecedented survey capabilities for dark energy, exoplanet, and general astrophysics", but directed the mission to "reduce cost and complexity sufficient to have a cost estimate consistent with the $3.2B cost target set at the beginning of Phase A." [27] NASA announced the reductions taken in response to this recommendation, and that WFIRST would proceed to its mission design review in February 2018 and begin Phase B by April 2018. [28] NASA confirmed that the changes made to the project had reduced its estimated life cycle cost to $3.2B and that the Phase B decision was on track for completion on April 11, 2018. [29]

The Trump administration's proposed FY2019 budget would terminate WFIRST, citing higher priorities within NASA and the increasing cost of this telescope.[7] The proposed cancellation of the project was met with criticism by professional astronomers, who noted that the American astronomical community had rated WFIRST the highest-priority space mission for the 2020s in the 2010 Decadal Survey.[8][9] The American Astronomical Society expressed "grave concern" about the proposed cancellation, and noted that the estimated lifecycle cost for WFIRST had not changed over the previous two years.[30] However, on March 22-23, Congress approved a FY18 WFIRST budget in excess of the administration's budget request for that year and stated that Congress "rejects the cancellation of scientific priorities recommended by the National Academy of Sciences decadal survey process", and further directed NASA to develop new estimates of WFIRST’s total and annual development costs.[29][10] Later, the President announced he had signed the bill March 23.[31]

Partnership

Space agencies from four nations and regions, namely CNES, DLR, ESA, and JAXA are currently in discussion with NASA to provide various components and support for WFIRST.[32][33] NASA has expressed interest in ESA contributions to the spacecraft, coronagraph and ground station support.[34] For the coronagraph instrument, contributions from Europe and Japan are being discussed.[34] A contribution from Germany's Max Planck Institute for Astronomy is under consideration, namely the filter wheels for the star-blocking mask inside the coronagraph.[35] The Japanese space agency JAXA is proposing to add an polarization module for the coronagraph, plus a polarization compensator. An accurate polarimetry capability on WFIRST may strengthen the science case for exoplanets and planetary disks, which shows polarization.[36][37] In addition to these potential partnerships, Australia has offered ground station contributions for the mission.[38]

In May 2018, NASA awarded a multi-year contract to Ball Aerospace to provide key components for the Wide Field Instrument on WFIRST.[39]

See also

References

- ↑ "WFIRST Observatory". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. 25 April 2014. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- 1 2 3 4 "WFIRST-AFTA Science Definition Team Final Report" (PDF). NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. 13 February 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- 1 2 "NASA Introduces New, Wider Set of Eyes on the Universe" (Press release). 2016-02-18. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ National Research Council (2010). New Worlds, New Horizons in Astronomy and Astrophysics. Washington, D.C.: National Research Council. ISBN 0-309-15802-8. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- 1 2 "WFIRST Science Definition Team 2015 Report" (PDF). 2015-03-10. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ↑ WFIRST Wide-Field Infrared Telescope Home Page, http://wfirst.gsfc.nasa.gov/about/

- 1 2 "FY 2019 budget estimates" (PDF). 2018-02-12. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- 1 2 Cofield, Calla (13 February 2018). "What Would it Mean for Astronomers if the WFIRST Space Telescope is Killed?". Space.com. Retrieved 2018-02-13.

- 1 2 Overbye, Dennis (19 February 2018). "Astronomers' Dark Energy Hopes Fade to Gray". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- 1 2 "Planetary science wins big in NASA's new spending plan". Jeffrey Brainard. Science AAAS. 23 March 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (2 April 2018). "Federal appropriations process is so extended that it's confusing what year we're in". Space News. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (2018-07-25). "NASA weighs delaying WFIRST to fund JWST overrun". Space News. Retrieved 2018-07-25.

- ↑ WFIRST Science Definition Team Final Report, 2012-08-15, arXiv:1208.4012, Bibcode:2012arXiv1208.4012G

- ↑ "Ex-Spy Telescope May Become a Space Investigator - NYTimes.com". 2012-06-04. Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- ↑ WFIRST-AFTA SDT Final Report, revision 1 (PDF), 2013-05-23, retrieved 2013-09-10

- ↑ Dan Leone (2013-06-04). "Only NASA Astrophysics Remains in Running for Donated NRO Telescope — For Now; SpaceNews article". Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ↑ NASA (2014-04-30). "WFIRST Science Definition Team Interim Report" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-08-28.

- ↑ Green & Schechter (2011-07-11). "WFIRST IDRM" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ↑ "WFIRST DRM1" (PDF). 2012-05-17. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ↑ Green & Schechter (2012-08-15). "WFIRST DRM2". arXiv:1208.4012. Bibcode:2012arXiv1208.4012G.

- ↑ Sullivan, John (2016-02-18). "Princeton professors to lead NASA science team probing universe and planets" (Press release). Princeton. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ Rauscher, Bernard. "Introduction to WFIRST H4RG-10 Detector Arrays" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-09-07.

- 1 2 Foust, Jeff (7 January 2016). "NASA's Next Major Space Telescope Project Officially Starts in February". Space.com. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ Daniel Clery (2016-02-19). "NASA moves ahead with its next space telescope". Science Magazine. Retrieved 2016-02-20.

- ↑ "NASA Astrophysics: Progress toward New Worlds, New Horizons, page 44" (PDF). NRC. 2015-10-08. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ↑ "NASA Taking a Fresh Look at Next Generation Space Telescope Plans". 2017-04-17. Retrieved 2017-10-19.

- ↑ "NASA Receives Findings from WFIRST Independent Review Team". 2017-10-19. Retrieved 2017-10-19.

- ↑ Jeff Foust (2018-01-09). "NASA plans to have WFIRST reviews complete by April". Space News. Retrieved 2018-01-11.

- 1 2 Jeff Foust (2018-03-28). "WFIRST work continues despite budget and schedule uncertainty". Space News. Retrieved 2018-04-03.

- ↑ Joel Parriott (2018-02-14). "American Astronomical Society Leaders Concerned with Proposed Cancellation of WFIRST". AAS. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- ↑ "President Signs FY 2018 Omnibus with $3 Billion NIH Increase, Boost for Other Health Programs". Tannaz Rasouli et al. AAMC. 23 March 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "2017.12.6 すばる小委員会 議事録" (PDF) (in Japanese). Subaru Telescope. 6 December 2017. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (January 9, 2018). "NASA plans to have WFIRST reviews complete by April". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- 1 2 Benford, Dominic (1 March 2016). "WFIRST Programmatic Overview" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- ↑ Zhao, Feng; Grady, Trauger (29 July 2018). "WFIRST Coronagraph Instrument (CGI) Status" (PDF). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- ↑ Yamada, Toru (10 January 2017). "WFIRST" (PDF). Subaru Telescope. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- ↑ Sumi, Takahiro; Yamada, Toru; Tamura, Motohide; Takada, Masahiro (5 January 2017). "WFIRST(Wide Field Infra Red Survey Telescope)" (in Japanese). JAXA. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- ↑ Gehrels, Neil; Grady, Kevin (21 July 2016). "WFIRST STATUS" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- ↑ Brown, Katherine (2018-05-23). "NASA Awards Contract for Space Telescope Mission". NASA. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope. |

- WFIRST page at Goddard Space Flight Center site

- WFIRST Science Data Center page at the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center (IPAC)

- "Astro2010 Report Release Presentation".

- $1.6 Billion Telescope Would Search Alien Planets and Probe Dark Energy — Space.com

- The WFIRST/AFTA astrophysics mission: bigger and better for exoplanets, Tom Greene

- NASA/ Goddard – WFIRST: Uncovering the Mysteries of the Universe on YouTube (min. 1:25) May 30, 2014

- WFIRST-AFTA: Coronograph Technology Development on YouTube (min. 4:20) Mar 16, 2015

- WFIRST: The Best of Both Worlds on YouTube (min. 3:14) Feb 18, 2016