Psyche (spacecraft)

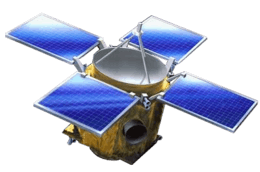

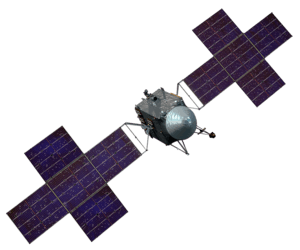

Artist's rendering of the Psyche spacecraft | |||||||||||

| Names | Discovery 14 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission type | Asteroid orbiter | ||||||||||

| Operator | NASA · ASU | ||||||||||

| Website |

NASA: www ASU: psyche | ||||||||||

| Mission duration |

Cruise: 3.5 years Science: 21 months in orbit (2026–2027) | ||||||||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||||||||

| Bus | SSL 1300[1] | ||||||||||

| Manufacturer | SSL[2] | ||||||||||

| Launch mass | 2,608 kg (5,750 lb)[3] | ||||||||||

| Start of mission | |||||||||||

| Launch date | mid-2022 | ||||||||||

| Launch site | Kennedy Space Center | ||||||||||

| 16 Psyche orbiter | |||||||||||

| Orbital insertion | 2026 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

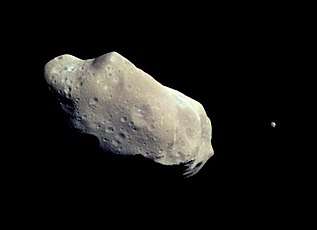

Psyche is a planned orbiter mission that will explore the origin of planetary cores by studying the metallic asteroid 16 Psyche.[4] Lindy Elkins-Tanton of Arizona State University is the Principal Investigator who proposed this mission for NASA's Discovery Program. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) will manage the project.

16 Psyche is the heaviest known M-type asteroid, and is thought to be the exposed iron core of a protoplanet.[5] This asteroid may be the remnant of a violent collision with another object that stripped off the outer crust. Radar observations of the asteroid from Earth indicate an iron–nickel composition.[6] On January 4, 2017, the Psyche mission was chosen along with the Lucy mission as NASA's next Discovery-class missions.[7]

History

Psyche was submitted as part of a call for proposals for NASA's Discovery Program that closed in February 2015. It was shortlisted on September 30, 2015, as one of five finalists and awarded $3 million for further concept development.[4][8] One aspect of selection was enduring the "site visit" in which about 30 NASA personnel come and interview, inspect, and question the proposers and their plan.[9]

On January 4, 2017, it was selected along with Lucy as one of two winners of this round of Discovery mission selection, with launch set for 2023 as the 14th Discovery mission.[10] In May 2017 the launch date was moved up to target a more efficient trajectory, launching in 2022 and arriving in 2026 with a Mars gravity assist in 2023.[11]

Mission overview

The Psyche spacecraft will use solar electric propulsion,[2][12] and the scientific payload will be an imager, a magnetometer, and a gamma-ray spectrometer.[12][13]

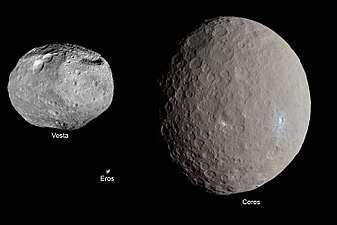

Data shows asteroid 16 Psyche to have a diameter of about 252 km (157 mi).[14] Scientists think that 16 Psyche could be the exposed core of an early planet that could have been as large as Mars and lost its surface in a series of violent collisions.[10]

The mission will launch in 2022 and arrive in four years to perform 21 months of science.[1][4][15][11] The spacecraft will be built by NASA JPL in collaboration with SSL (formerly Space Systems/Loral) and Arizona State University.[16]

Science goals and objectives

.png)

Differentiation was a fundamental process in shaping many asteroids and all terrestrial planets, and direct exploration of a core could greatly enhance understanding of this process. The Psyche mission will characterize 16 Psyche's geology, shape, elemental composition, magnetic field, and mass distribution. It is expected that this mission will increase the understanding of planetary formation and interiors.

Specifically, the science goals for the mission are:

- Understand a previously unexplored building block of planet formation: iron cores.

- Look inside terrestrial planets, including Earth, by directly examining the interior of a differentiated body, which otherwise could not be seen.

- Explore a new type of world, made of metal.

The science objectives are:

- Determine whether 16 Psyche is a core, or if it is unmelted material.

- Determine the relative ages of regions of 16 Psyche's surface.

- Determine whether small metal bodies incorporate the same light elements as are expected in the Earth's high-pressure core.

- Determine whether 16 Psyche was formed under conditions more oxidizing or more reducing than Earth's core.

- Characterize 16 Psyche's topography.

The science questions this mission will address are:[5]

- Is 16 Psyche the stripped core of a differentiated planetesimal, or was it formed as an iron-rich body? What were the building blocks of planets? Did planetesimals that formed close to the Sun have very different bulk compositions?

- If 16 Psyche was stripped of its mantle, when and how did that occur?

- If 16 Psyche was once molten, did it solidify from the inside out, or the outside in?

- Did 16 Psyche produce a magnetic dynamo as it cooled?

- What are the major alloy elements that coexist in the iron metal of the core?

- What are the key characteristics of the geologic surface and global topography? Does 16 Psyche look radically different from known stony and icy bodies?

- How do craters on a metal body differ from those in rock or ice?

Orbit regime

The Psyche spacecraft would orbit 16 Psyche at decreasing altitudes.[1] Its first regime, Orbit A, will see the spacecraft enter a 700 km (430 mi) orbit for magnetic field characterization and preliminary mapping for a duration of 56 days. It will then descend to Orbit B, set at 290 km (180 mi) altitude for 76 days, for topography and magnetic field characterization. It will then descend to Orbit C, at 170 km (110 mi) altitude for 100 days to perform gravity investigations and continue magnetic field observations. Finally, the orbiter will enter Orbit D, set at 85 km (53 mi) to determine the chemical composition of the surface using its gamma-ray and neutron spectrometers. It will also acquire continued imaging, gravity, and magnetic field mapping. The mission is planned to orbit the asteroid for at least 21 months.[1]

Science payload

Psyche will fly a payload of 30 kg (66 lb),[3] consisting on four scientific instruments.[9]

- The Multispectral Imager will provide high-resolution images using filters to discriminate between metallic and silicate constituents.

- The Gamma-ray and Neutron Spectrometer will analyze and map the asteroid's elemental composition.

- The Magnetometer will measure and map the remnant magnetic field of the asteroid.

- The X-band Gravity Science Investigation will use the X-band (microwave) radio telecommunications system to measure the asteroid's gravity field and deduce its interior structure.

The spacecraft will also test an experimental laser communication technology called Deep Space Optical Communications.[18] It is hoped that the device will be able to increase spacecraft communications performance and efficiency by 10 to 100 times over conventional means.[18][19] The laser beams from the spacecraft will be received by a ground telescope at Palomar Observatory in California.[20]

Propulsion

| SPT-140 | Parameter/units[21][22] |

|---|---|

| Type | Hall-effect thruster |

| Power | Max: 4.5 kW Min: 900 W At 16 Psyche: ≤ 1 kW |

| Specific impulse (Isp) | 1800 s |

| Total impulse | 8.2 MN·s |

| Thrust | 280 mN [22] |

| Thruster mass | 8.5 kg |

| Propellant mass | ≈ 425 kg of xenon[22] |

This mission will use the model SPT-140 engine, a Hall-effect thruster utilizing solar electric propulsion, where electricity generated from solar panels is transmitted to an electric, rather than chemically powered, rocket engine.[2][23][24] The thruster is nominally rated at 4.5 kW operating power,[25] but it will also operate for long durations at about 900 watts.[23]

The SPT-140 (SPT stands for Stationary Plasma Thruster) is a production line commercial propulsion system[3] that was invented in Russia by OKB Fakel and developed by NASA's Glenn Research Center, Space Systems Loral, and Pratt & Whitney since the late 1980s.[26][27] The SPT-140 thruster was first tested in US as a 3.5 kW unit in 2002 as part of the Air Force Integrated High Payoff Rocket Propulsion Technology program.[25][3] Using solar electric thrusters will allow the spacecraft to arrive at 16 Psyche (at 3.3 astronomical units) much faster and consume 10% the fuel than it could using conventional chemical propulsion.

Electricity will be generated by bilateral solar panels in an x-shaped configuration.[28]

See also

- DAVINCI, a proposed atmospheric probe to Venus

- Iron meteorite

- Near-Earth Object Camera (NEOcam), a proposed space telescope

- VERITAS, a proposed Venus orbiter

References

- 1 2 3 4 Oh, David Y.; Collins, Steve; Goebel, Dan; Hart, Bill; Lantoine, Gregory; Snyder, Steve; Whiffen, Greg; Elkins-Tanton, Linda; Lord, Peter; Pirkl, Zack; Rotlisburger, Lee (2017). Development of the Psyche Mission for NASA’s Discovery Program (PDF). 35th International Electric Propulsion Conference. October 8–12, 2017. Atlanta, Georgia. IEPC-2017-153.

- 1 2 3 4 Agle, D. C.; Russell, Jimi; Cantillo, Laurie; Brown, Dwayne (September 28, 2017). "NASA Glenn Tests Thruster Bound for Metal World". NASA. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Lord, Peter W.; van Ommering, Gerrit (2015). Evolved Commercial Solar Electric Propulsion: A Foundation for Major Space Exploration Missions (PDF). 31st Space Symposium, Technical Track. April 13–14, 2015. Colorado Springs, Colorado.

- 1 2 3 Chang, Kenneth (January 6, 2017). "A Metal Ball the Size of Massachusetts That NASA Wants to Explore". The New York Times. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- 1 2 Elkins-Tanton, L. T.; et al. (2014). Journey to a Metal World: Concept for a Discovery Mission to Psyche (PDF). 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. March 17–21, 2014. The Woodlands, Texas. 1253. Bibcode:2014LPI....45.1253E. LPI Contribution No. 1777.

- ↑ Shepard, Michael K.; et al. (January 2017). "Radar observations and shape model of asteroid 16 Psyche". Icarus. 281: 388–403. Bibcode:2017Icar..281..388S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.08.011.

- ↑ Grush, Loren (January 4, 2017). "In the 2020s NASA will launch spacecraft to study Jupiter's asteroids, and another made of metal". The Verge. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ Brown, Dwayne C.; Cantillo, Laurie (September 30, 2015). "NASA Selects Investigations for Future Key Planetary Mission". NASA. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- 1 2 Valentine, Karin (December 20, 2016). "Journey to a metal world". ASU Now. Arizona State University.

- 1 2 Brown, Dwayne C.; Cantillo, Laurie (January 4, 2017). "NASA Selects Two Missions to Explore the Early Solar System". NASA. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- 1 2 Agle, D. C.; Valentine, Karin; Cantillo, Laurie; Brown, Dwayne (May 24, 2017). "NASA Moves Up Launch of Psyche Mission to a Metal Asteroid". NASA. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- 1 2 Kane, Van (February 19, 2014). "Mission to a Metallic World: A Discovery Proposal to Fly to the Asteroid Psyche". The Planetary Society. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ↑ Wampler, Stephen (November 4, 2015). "Lab-Johns Hopkins team tapped to work on possible NASA effort to explore asteroid". Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ↑ "16 Psyche". JPL Small-Body Database. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ↑ Hand, Eric (September 30, 2015). "Venus and a bizarre metal asteroid are leading destinations for low-cost NASA missions". Science. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ↑ Lewis, Wendy (October 26, 2015). "SSL is JPL Industrial Partner for NASA Asteroid Exploration Mission Opportunity". SSL. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (January 31, 2016). "Hunt for Antarctica's 'lost meteorites'". BBC News. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- 1 2 David, Leonard (October 18, 2017). "Deep Space Communications via Faraway Photons". NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ↑ Greicius, Tony (September 14, 2017). "Psyche Overview". NASA. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ↑ Hall, Loura, ed. (October 18, 2017). ""Lighten Up" – Deep Space Communications via Faraway Photons". NASA.

- ↑ Myers, Roger. "Solar Electric Propulsion: Introduction, Applications and Status" (PDF). Aerojet Rocketdyne.

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Ian K.; Kay, Ewan; Lee, Ty; Bae, Ryan; Feher, Negar (2017). New Avenues for Research and Development of Electric Propulsion Thrusters at SSL (PDF). 35th International Electric Propulsion Conference. October 8–12, 2017. Atlanta, Georgia. IEPC-2017-400.

- 1 2 Cole, Michael (October 9, 2017). "NASA Glenn tests solar electric propulsion thruster for journey to metal world". Spaceflight Insider.

- ↑ DeFelice, David (August 18, 2015). "NASA – Ion Propulsion". NASA. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- 1 2 "T-140". University of Michigan Plasmadynamics & Electric Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Native Electric Propulsion Engines Today" (in Russian). Novosti Kosmonavtiki. 1999. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011.

- ↑ Delgado, Jorge J.; Corey, Ronald L.; Murashko, Vjacheslav M.; Koryakin, Alexander I.; Pridanikov, Sergei Y. (2014). Qualification of the SPT-140 for use on Western Spacecraft. 50th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference. July 28–30, 2014. Cleveland, Ohio. doi:10.2514/6.2014-3606. AIAA 2014–3606.

- ↑ Agle, D. C.; Valentine, Karin; Cantillo, Laurie; Brown, Dwayne C. (May 24, 2017). "NASA Moves Up Launch of Psyche Mission to a Metal Asteroid". NASA.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Psyche (spacecraft). |

- Mission website at NASA.gov

- Mission website by Arizona State University