Next-Generation Transit Survey

| |||||

| |||||

The Next-Generation Transit Survey (NGTS) is a ground-based robotic search for exoplanets. The facility is located at Paranal Observatory in the Atacama desert in northern Chile, about 2 km from ESO's Very Large Telescope and 0.5 km from the VISTA Survey Telescope. Science operations began in early 2015.[1] The astronomical survey is managed by a consortium of seven European universities and other academic institutions from Chile, Germany, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.[2] Prototypes of the array were tested in 2009 and 2010 on La Palma, and from 2012 to 2014 at Geneva Observatory.[2]

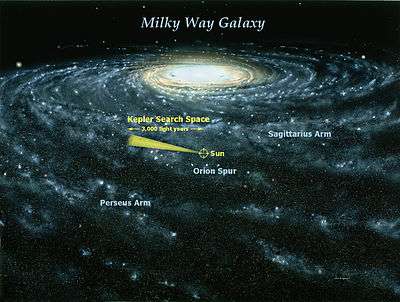

The aim of NGTS is to discover super-Earths and exo-Neptunes transiting relatively bright and nearby stars with an apparent magnitude of up to 13. The survey uses transit photometry, which precisely measures the dimming of a star to detect the presence of a planet when it crosses in front of it. NGTS consists of an array of twelve commercial 0.2-metre telescopes (f/2.8), each equipped with a red-sensitive CCD camera operating in the visible and near-infrared at 600–900 nm. The array covers an instantaneous field of view of 96 square degrees (8 deg2 per telescope) or around 0.23% of the entire sky.[3] NGTS builds heavily on experience with SuperWASP, using more sensitive detectors, refined software, and larger optics, though having a much smaller field of view.[4] Compared to the Kepler spacecraft with its original Kepler field of 115 square degrees, the sky area covered by NGTS will be sixteen times larger, because the survey intends to scan four different fields every year over a period of four years. As a result, the sky coverage will be comparable to that of Kepler's K2 phase.[3]

NGTS is designed to fill the current gap between Earth-sized planets and gas giants. Although other ground-based surveys could only detect larger, Jupiter-sized exoplanets, Kepler's Earth-sized planets are often too far away or orbit stars too dim to allow for doppler spectroscopy—a different detection method to determine the planet's mass by the wobble of its host star. NGTS's wider field of view enables it to detect a larger number of more-massive planets around brighter stars. With a detailed follow-up characterization by larger instruments such as HARPS, ESPRESSO and VLT-SPHERE, it will be possible to measure the mass of a large number of targets using this wobble method. This makes it possible to determine the exoplanet's density, and hence whether it is gaseous or rocky.[5][6]

On 31 October 2017, the discovery of NGTS-1b, a confirmed hot Jupiter-sized extrasolar planet orbiting NGTS-1, an M-dwarf star, about half the mass and radius of the Sun, every 2.65 days, was reported by the survey team.[7][8][9] Daniel Bayliss, of the University of Warwick, and lead author of the study describing the discovery of NGTS-1b, stated, "The discovery of NGTS-1b was a complete surprise to us—such massive planets were not thought to exist around such small stars – importantly, our challenge now is to find out how common these types of planets are in the Galaxy, and with the new Next-Generation Transit Survey facility we are well-placed to do just that."[9]

Science mission

Ground-based surveys for extrasolar planets such as WASP and the HATNet Project have discovered many large exoplanets, mainly Saturn- and Jupiter-sized gas giants. Space-based missions such as CoRoT and the Kepler survey have extended the results to smaller objects, including rocky super-Earth- and Neptune-sized exoplanets.[3] Orbiting space missions have a higher accuracy of stellar brightness measurement than is possible via ground-based measurements, but they have probed a relatively small region of sky. Unfortunately, most of the smaller candidates orbit stars that are too faint for confirmation by radial-velocity measurements. The masses of these smaller candidate planets are hence either unknown or poorly constrained, such that their bulk composition cannot be estimated.[3]

By focusing on super-Earth- to Neptune-sized targets orbiting cool, small, but bright stars of K and early-M spectral type, over an area considerably larger than that covered by space missions, NGTS is intended to provide prime targets for further scrutiny by telescopes such as the Very Large Telescope (VLT), European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT), and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Such targets are more readily characterized in terms of their atmospheric composition, planetary structure, and evolution than smaller targets orbiting larger stars.[2]

In follow-up observations by larger telescopes, powerful means will be available to probe the atmospheric composition of exoplanets discovered by NGTS. For example, during secondary eclipse, when the star occults the planet, a comparison between the in-transit and out-of-transit flux allows computation of a difference spectrum representing the thermal emission of the planet.[10] Calculation of the transmission spectrum of the planet's atmosphere can be obtained by measuring the small spectral changes in the spectrum of the star that arise during the planet's transit. This technique requires an extremely high signal-to-noise ratio, and has thus far been successfully applied to only a few planets orbiting small, nearby, relatively bright stars, such as HD 189733 b and GJ 1214 b. NGTS is intended to greatly increase the number of planets that area analyzable using such techniques.[10] Simulations of expected NGTS performance reveal the potential of discovering approximately 231 Neptune- and 39 super-Earth-sized planets amenable to detailed spectrographic analysis by the VLT, compared to only 21 Neptune- and 1 super-Earth-sized planets from the Kepler data.[3]

Instrument

Development

The scientific goals of the NGTS require being able to detect transits with a precision of 1 mmag at 13th magnitude. Although at ground level this level of accuracy was routinely achievable in narrow-field observations of individual objects, it was unprecedented for a wide-field survey.[3] To achieve this goal, the designers of the NGTS instruments drew upon an extensive hardware and software heritage from the WASP project, in addition to developing many refinements in prototype systems operating on La Palma during 2009 and 2010, and at the Geneva Observatory from 2012 to 2014.[5]

Telescope array

NGTS employs an automated array of twelve 20-centimeter f/2.8 telescopes on independent equatorial mounts and operating at orange to near-infrared wavelengths (600–900 nm). It is located at the European Southern Observatory's Paranal Observatory in Chile, a location noted for low water-vapor and excellent photometric conditions.

Combined search

The NGTS telescope project cooperates closely with ESO's large telescopes. ESO facilities available for follow-up studies include the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) at La Silla Observatory; ESPRESSO for radial-velocity measurements at the VLT; SPHERE, an adaptive optics system and coronagraphic facility at the VLT that directly images extrasolar planets;[11] and a variety of other VLT and planned E-ELT instruments for atmospheric characterization.[3]

Partnership

Although located at Paranal Observatory, NGTS is not in fact operated by ESO, but by a consortium of seven academic institutions from Chile, Germany, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom:[2]

See also

Other exoplanet search projects

- HATNet Project (HAT)

- Miniature Exoplanet Radial Velocity Array (MINERVA)

- Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope (KELT)

- Trans-Atlantic Exoplanet Survey (TrES)

- XO Telescope

References

- ↑ "New Exoplanet-hunting Telescopes on Paranal". European Southern Observatory. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "About NGTS". Next Generation Transit Survey. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wheatley, P. J.; Pollacco, D. L.; Queloz, D.; Rauer, H.; Watson, C. A.; West, R. G.; Chazelas, B.; Louden, T. M.; Walker, S.; Bannister, N.; Bento, J.; Burleigh, M.; Cabrera, J.; Eigmüller, P.; Erikson, A.; Genolet, L.; Goad, M.; Grange, A.; Jordán, A. S.; Lawrie, K.; McCormac, J.; Neveu, M. (2013). "The Next Generation Transit Survey (NGTS)" (PDF). EPJ Web of Conferences. 47: 13002. arXiv:1302.6592. Bibcode:2013EPJWC..4713002W. doi:10.1051/epjconf/20134713002.

- ↑ "Searching for Super-Earths" (PDF). Queen's University. 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- 1 2 McCormac, J.; Pollacco, D.; The NGTS Consortium. "The Next Generation Transit Survey Prototyping Phase" (PDF). Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ Daniel Clery (14 January 2015). "New exoplanet hunter opens its eyes to search for super-Earths". Science.

- ↑ Bayliss, Daniel; Gillen, Edward; Eigmuller, Philipp; McCormac, James; Alexander, Richard D; Armstrong, David J; Booth, Rachel S; Bouchy, Francois; Burleigh, Matthew R; Cabrera, Juan; Casewell, Sarah L; Chaushev, Alexander; Chazelas, Bruno; Csizmadia, Szilard; Erikson, Anders; Faedi, Francesca; Foxell, Emma; Gansicke, Boris T; Goad, Michael R; Grange, Andrew; Gunther, Maximilian N; Hodgkin, Simon T; Jackman, James; Jenkins, James S; Lambert, Gregory; Louden, Tom; Metrailler, Lionel; Moyano, Maximiliano; Pollacco, Don; et al. (2017). "NGTS-1b: A hot Jupiter transiting an M-dwarf". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 475 (4): 4467. arXiv:1710.11099. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx2778.

- ↑ Lewin, Sarah (31 October 2017). "Monster Planet, Tiny Star: Record-Breaking Duo Puzzles Astronomers". Space.com. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- 1 2 Staff (31 October 2017). "'Monster' planet discovery challenges formation theory". Phys.org. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- 1 2 "NGTS Science Programme". Next Generation Transit Survey. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ "SPHERE - Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch". European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

External links

- The Next Generation Transit Survey Becomes Operational at Paranal, ESO archive, The Messenger 165 – September 2016

_at_Paranal_(1502d).jpg)

_at_Paranal_(1502f).jpg)

_at_Paranal_(1502c).jpg)

_at_Paranal_(1502b).jpg)