List of nearest exoplanets

There are 3,851 known exoplanets, or planets outside our solar system that orbit a star, as of October 1, 2018; only a small fraction of these are located in the vicinity of the Solar System.[2] Within 10 parsecs (32.6 light-years), there are 56 exoplanets listed as confirmed by the NASA Exoplanet Archive.[a][3] Among the over 400 known stars within 10 parsecs,[b][4] 26 have been confirmed to have planetary systems; 51 stars in this range are visible to the naked eye,[c][5] eight of which have planetary systems.

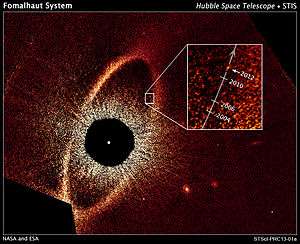

The first report of an exoplanet within this range was in 1998 for a planet orbiting around Gliese 876 (15.3 light-years (ly) away), and the latest as of 2017 is one around Ross 128 (11 ly). The closest exoplanet found is Proxima Centauri b, which was confirmed in 2016 to orbit Proxima Centauri, the closest star to our Solar System (4.25 ly). HD 219134 (21.6 ly) has six exoplanets, the highest number discovered for any star within this range. A planet around Fomalhaut (25 ly) was, in 2008, the first planet to be directly imaged.[6]

Most known nearby exoplanets orbit close to their star and have highly eccentric orbits. A majority are significantly larger than Earth, but a few have similar masses, including two planets (around YZ Ceti, 12 ly) which may be less massive than Earth. Several confirmed exoplanets are hypothesized to be potentially habitable, with Proxima Centauri b and three around Gliese 667 C (23.6 ly) considered the most likely candidates.[7] The International Astronomical Union took a public survey in 2015 about renaming some known extrasolar bodies, including the planets around Epsilon Eridani (10.5 ly) and Fomalhaut.[d][8]

Exoplanets within 10 parsecs

| ° | Mercury, Earth and Jupiter (for comparison purposes) |

| # | Confirmed multiplanetary systems |

| ↑ | Exoplanets believed to be potentially habitable[7] |

| Host star system | Companion exoplanet (in order from star) | Notes and additional planetary observations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Distance (ly) |

Apparent magnitude (V) |

Mass (M☉) |

Label [e] |

Mass (M⊕)[f] |

Radius (R⊕) |

Semi-major axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity |

Inclination (°) |

Discovery year | |

| Sun° | 0 | −26.7 | 1 | Mercury | 0.055 | 0.3829 | 0.387 | 88.0 | 0.205 | — | — | — |

| Earth | 1 | 1 | 1 | 365.3 | 0.0167 | — | — | |||||

| Jupiter | 317.8 | 10.973 | 5.20 | 4,333 | 0.0488 | — | — | |||||

| Proxima Centauri | 4.2441 | 11.13 | 0.123 | b↑ | >1.3 | ~1.1 | 0.0485 | 11.2 | <0.35 | — | 2016 | [9][7] |

| Epsilon Eridani | 10.446 | 3.73 | 0.83 | AEgir | 500 | — | 3.39 | 2,500 | 0.70 | 30 | 2000 | 1 candidate and a disc[10][11] |

| Ross 128 | 11.007 | 11.1 | 0.168 | b↑ | >1.4 | ~1.2 | 0.0496 | 9.87 | 0.12 | — | 2017 | [12] |

| Tau Ceti# | 11.753 | 3.50 | 0.78 | g | >1.7 | — | 0.133 | 20.0 | 0.06 | — | 2017 | 2 retracted and 1 candidate [13][14][7][15][16][17] |

| h | >1.8 | — | 0.243 | 49.4 | 0.23 | — | 2017 | |||||

| e↑ | >3.9 | ~1.6 | 0.538 | 163 | 0.18 | — | 2017 | |||||

| f | >3.9 | — | 1.33 | 640 | 0.16 | — | 2017 | |||||

| YZ Ceti# | 12.108 | 12.1 | 0.130 | b | >0.75 | — | 0.0156 | 1.97 | 0.0 | — | 2017 | 1 candidate [18][19] |

| c | >0.98 | — | 0.0209 | 3.06 | 0.04 | — | 2017 | |||||

| d | >1.1 | — | 0.0276 | 4.66 | 0.13 | — | 2017 | |||||

| Luyten's Star# | 12.199 | 11.94 | 0.29 | c | >1.2 | — | 0.0365 | 4.72 | 0.17 | — | 2017 | [7][20] |

| b↑ | >2.9 | ~1.4 | 0.091 | 18.6 | 0.10 | — | 2017 | |||||

| Kapteyn's Star | 12.829 | 8.8 | 0.28 | c | >7 | — | 0.311 | 122 | 0.23 | — | 2014 | 1 candidate[21][22] |

| Wolf 1061# | 14.046 | 10.1 | 0.25 | b | >1.9 | — | 0.0375 | 4.89 | 0.15 | — | 2015 | [7][23] |

| c↑ | >3.4 | ~1.5 | 0.0890 | 17.9 | 0.11 | — | 2015 | |||||

| d | >8 | — | 0.470 | 217 | 0.55 | — | 2015 | |||||

| Gliese 674 | 14.839 | 9.38 | 0.35 | b | >11 | 12.4 | 0.039 | 4.69 | 0.20 | — | 2007 | [24][25] |

| Gliese 687 | 14.840 | 9.15 | 0.41 | b | >18 | — | 0.164 | 38.1 | 0.04 | — | 2014 | [26] |

| Gliese 876# | 15.250 | 10.2 | 0.33 | d | 6.8 | — | 0.0208 | 1.94 | 0.21 | 59 | 2005 | 2 candidates [27][28][29] |

| c | 230 | — | 0.130 | 30.1 | 0.256 | 59 | 2000 | |||||

| b | 720 | — | 0.208 | 61.1 | 0.032 | 59 | 1998 | |||||

| e | 15 | — | 0.334 | 124 | 0.055 | 59 | 2010 | |||||

| Gliese 832# | 16.194 | 8.67 | 0.45 | c↑ | >5.4 | ~1.7 | 0.163 | 35.7 | 0.18 | — | 2014 | [7][30] |

| b | >220 | — | 3.56 | 3,700 | 0.08 | — | 2008 | |||||

| 40 Eridani A | 16.386 | 4.4 | 0.84 | Ab | >8.5 | — | 0.224 | 42.4 | 0.04 | — | 2018 | [31] |

| LHS 1723# | 17.533 | 12.2 | 0.164 | b↑ | >2.0 | ~1.3 | 0.0328 | 5.36 | 0.2 | — | 2017 | [32] |

| c | >2.3 | — | 0.126 | 40.5 | 0.2 | — | 2017 | |||||

| Gliese 752 A | 19.286 | 9.13 | 0.46 | Ab | >12.2 | — | 0.336 | 106 | 0.16 | — | 2018 | [33] |

| 82 G. Eridani# | 19.582 | 4.26 | 0.85 | b | >2.7 | — | 0.121 | 18.3 | ~0 | 90 | 2011 | 2 candidates and a disc [34][35][36] |

| c | >2.4 | — | 0.204 | 40.1 | ~0 | 90 | 2011 | |||||

| d | >4.8 | — | 0.350 | 90 | ~0 | 90 | 2011 | |||||

| e | >4.8 | — | 0.509 | 147 | 0.29 | — | 2017 | |||||

| Gliese 581# | 20.545 | 10.5 | 0.31 | e | >1.7 | — | 0.0282 | 3.15 | 0.0 | — | 2009 | 3 candidates and a disc [37][38][39][40] |

| b | >16 | — | 0.0406 | 5.37 | 0.0 | — | 2005 | |||||

| c | >5.5 | — | 0.072 | 12.9 | 0.0 | — | 2007 | |||||

| Gliese 625 | 21.114 | 10.2 | 0.30 | b | >2.8 | — | 0.0784 | 14.6 | ~0.1 | — | 2017 | [41] |

| HD 219134# | 21.306 | 5.57 | 0.78 | b | 4.7 | 1.60 | 0.0388 | 3.09 | ~0 | 85 | 2015 | 1 candidate [42][43] |

| c | 4.4 | 1.51 | 0.065 | 6.77 | 0.062 | 87 | 2015 | |||||

| f | >7.3 | >1.31 | 0.146 | 22.7 | 0.15 | — | 2015 | |||||

| d | >16 | >1.61 | 0.235 | 46.9 | 0.138 | — | 2015 | |||||

| g | >11 | — | 0.375 | 94 | ~0 | — | 2015 | |||||

| h | >110 | — | 3.11 | 2,200 | 0.06 | — | 2015 | |||||

| Gliese 667# | 23.632 | 10.2 | 0.33 | Cb | >5.6 | — | 0.051 | 7.20 | ~0.1 | — | 2009 | 2 candidates [44][7][45][46] |

| Cc↑ | >3.8 | ~1.5 | 0.125 | 28.1 | 0.02 | — | 2011 | |||||

| Cf↑ | >2.7 | ~1.4 | 0.156 | 39 | 0.03 | — | 2013 | |||||

| Ce↑ | >2.7 | ~1.4 | 0.213 | 62 | 0.02 | — | 2013 | |||||

| Cg | >4.6 | — | 0.549 | 260 | 0.08 | — | 2013 | |||||

| Fomalhaut | 25.126 | 1.16 | 1.92 | Dagon | ~800 | 13.5 | 160 | 560,000 | ~0.9 | 55 | 2008 | multiple discs[47][48] |

| 61 Virginis# | 27.741 | 4.74 | 0.95 | b | >5.1 | — | 0.0502 | 4.22 | ~0.1 | — | 2009 | a debris disc [49] |

| c | >18 | — | 0.218 | 38.0 | 0.14 | — | 2009 | |||||

| d | >23 | — | 0.476 | 123 | 0.35 | — | 2009 | |||||

| HD 192310# | 28.699 | 6.13 | 0.78 | b | >17 | — | 0.32 | 75 | 0.13 | 90 | 2010 | [50] |

| c | >24 | — | 1.18 | 530 | ~0.3 | 90 | 2011 | |||||

| Gliese 849 | 28.711 | 10.4 | 0.49 | b | >310 | — | 2.35 | 1,880 | 0.04 | — | 2006 | 1 candidate[51][52] |

| Gliese 433 | 29.572 | 9.79 | 0.48 | b | >5.8 | — | 0.060 | 7.37 | 0.08 | — | 2009 | 1 candidate[53][54] |

| HD 102365 | 30.374 | 4.89 | 0.85 | b | >16 | — | 0.46 | 122 | 0.34 | — | 2010 | [55] |

| Gliese 176 | 30.879 | 10.1 | 0.45 | b | >9 | — | 0.066 | 8.78 | ~0 | — | 2007 | 1 candidate[56][57] |

Excluded objects

Unlike for bodies within our Solar System, there is no clearly established method for officially recognizing an exoplanet. According to the International Astronomical Union, an exoplanet should be considered confirmed if it has not been disputed for five years after its discovery.[58] There have been examples where the existence of exoplanets has been proposed, but even after follow-up studies their existence is still considered doubtful by some astronomers. Such cases include: Alpha Centauri (4.36 ly, two in 2012[59] and 2013[60]), Lalande 21185 (8.31 ly, in 2017[61]), Groombridge 34 (11.7 ly, two in 2014[62] and 2017[63]), Epsilon Indi (11.8 ly, in 2018[64]), LHS 288 (15.6 ly, in 2007[65]), 40 Eridani (16.3 ly, in 2018[66]), Gliese 682 (16.6 ly, two in 2014[7][67][68]), and Gliese 229 (18.8 ly, in 2014[69]). There are also some instances where proposed exoplanets were later disproved by subsequent studies, such as candidates around Teegarden's star (12.6 ly),[70] Van Maanen 2 (13.9 ly),[71] Groombridge 1618 (15.9 ly),[72] and VB 10 (18.7 ly).[73]

The Working Group on Extrasolar Planets of the International Astronomical Union adopted in 2003 a working definition on the upper limit for what constitutes a planet: not being massive enough to sustain thermonuclear fusion of deuterium. Some studies have calculated this to be somewhere around 13 times the mass of Jupiter, and therefore objects more massive than this are usually classified as brown dwarfs.[74] Some proposed candidate exoplanets were later shown to be massive enough to fall above the threshold, and are likely brown dwarfs, as was the case for: SCR 1845-6357 B (12.6 ly),[75] SDSS J1416+1348 B (29.7 ly),[76] and WISE 1217+1626 B (30 ly).[77]

Excluded from the current list are known examples of potential free-floating sub-brown dwarfs, or "rogue planets", which are bodies that are too small to undergo fusion yet they do not revolve around a star. Known such examples include: WISE 0855–0714 (7.3 ly),[78] UGPS 0722-05, (13 ly)[79] WISE 1541−2250 (18.6 ly),[80] and SIMP J01365663+0933473 (20 ly).[81]

Statistics

Planetary systems

|

|

|

Exoplanets

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- ^ Listed values are primarily taken from NASA Exoplanet Archive,[3] but other databases include a few additional exoplanet entries tagged as "Confirmed" that are have yet to be compiled into the NASA archive. Such databases include:

- "Exoplanet Catalog". The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Full table.

- "Exoplanets Data Explorer". Exoplanet Orbit Database. California Planet Survey. Click the "+" button to visualize additional parameters.

- "Open Exoplanet Catalogue". Click the "Show options" to visualize additional parameters.

- ^ For reference, the 104th closest known star system in November 2016 was 82 Eridani (19.7 ly).[84]

- ^ According to the Bortle scale, an astronomical object is visible to the naked eye under "typical" dark-sky conditions in a rural area if it has an apparent magnitude smaller than +6.5. To the unaided eye, the limiting magnitude is +7.6 to +8.0 under "excellent" dark-sky conditions (with effort).[82]

- ^ The star Epsilon Eridani was named Ran (after Rán, the Norse goddess of the sea), and the planet Epsilon Eridani b was named AEgir (after Ægir, Rán's husband),[85] while the planet Fomalhaut b was named Dagon (after Dagon, an ancient Syrian “fish god”[86]).[8]

- ^ Exoplanet naming convention assigns uncapitalized letters starting from b to each planet based on chronological order of their initial report, and in increasing order of distance from the parent star for planets reported at the same time. Omitted letters signify planets that have yet to be confirmed, or planets that have been retracted altogether.

- ^ Most reported exoplanet masses have very large error margins (typically, between 10% and 30%). The mass of an exoplanet has generally been inferred from measurements on changes in the radial velocity of the host star, but this kind of measurement only allows for an estimate on the exoplanet's orbital parameters, but not on their orbital inclination (i). As such, most exoplanets only have an estimated minimum mass (Mreal*sin(i)), where their true masses are statistically expected to come close to this minimum, with only about 13% chance for the mass of an exoplanet to be more than double its minimum mass.[87]

References

- ↑ Harrington, J. D.; Villard, Ray (2013-08-01). "NASA's Hubble Reveals Rogue Planetary Orbit For Fomalhaut". NASA. Archived from the original on 2015-11-06. Retrieved 2015-09-18.

- ↑ Schneider, Jean. "Interactive Extra-solar Planets Catalog". The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- 1 2 3 "NASA Exoplanet Archive—Confirmed Planets". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "Stars within 10 parsecs". Solstation.com. 2014-04-25. Archived from the original on 2017-10-26. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ Powell, Richard (2006). "Stars within 50 light years". An Atlas of the Universe. Archived from the original on 2014-06-27. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ Sessions, Larry; Byrd, Deborah (2017-09-22). "Fomalhaut had first visible exoplanet". Earthsky.org. Archived from the original on 2018-03-26. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "The Habitable Exoplanets Catalog". Planetary Habitability Laboratory. University of Puerto Rico in Arecibo. 2015-09-01. Archived from the original on 2016-01-09. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- 1 2 "Final Results of NameExoWorlds Public Vote Released" (Press release). International Astronomical Union. 2015-12-15. Archived from the original on 2018-05-15. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ↑ "Proxima Cen". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "eps Eri". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2016-04-23.

- ↑ "eps Eridani c". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ "Ross 128". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "tau Cet". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "tau Ceti". Open Exoplanet Catalogue. Archived from the original on 2014-03-14. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ "tau Cet b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "tau Cet c". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "tau Cet d". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "YZ Cet". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "YZ Cet e". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2017-08-15. Archived from the original on 2018-03-19. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 273". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "Kapteyn". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "Kapteyn's b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2015-05-13. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "Wolf 1061". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 674". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 674 b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2007-04-25. Archived from the original on 2014-02-10. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ "GJ 687". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 876". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 876 f". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2016-02-23. Archived from the original on 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 876 g". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 832". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ Ma, Bo; Ge, Jian; Muterspaugh, Matthew; Singer, Michael A; Henry, Gregory W; González Hernández, Jonay I; Sithajan, Sirinrat; Jeram, Sarik; Williamson, Michael; Stassun, Keivan; Kimock, Benjamin; Varosi, Frank; Schofield, Sidney; Liu, Jian; Powell, Scott; Cassette, Anthony; Jakeman, Hali; Avner, Louis; Grieves, Nolan; Barnes, Rory; Zhao, Bo; Gilda, Sankalp; Grantham, Jim; Stafford, Greg; Savage, David; Bland, Steve; Ealey, Brent (October 2018). "The first super-Earth detection from the high cadence and high radial velocity precision Dharma Planet Survey". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 480 (2): 2411–2422. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty1933.

- ↑ "GJ 3323". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ Kaminski, A.; Trifonov, T.; Caballero, J. A.; Quirrenbach, A.; Ribas, I.; Reiners, A.; Amado, P. J.; Zechmeister, M.; Dreizler, S.; Perger, M.; Tal-Or, L.; Bonfils, X.; Mayor, M.; Astudillo-Defru, N.; Bauer, F. F.; Béjar, V. J. S.; Cifuentes, C.; Colomé, J.; Cortés-Contreras, M.; Delfosse, X.; Díez-Alonso, E.; Forveille, T.; Guenther, E. W.; Hatzes, A. P.; Henning, Th; Jeffers, S. V.; Kürster, M.; Lafarga, M.; Luque, R.; Mandel, H.; Montes, D.; Morales, J. C.; Passegger, V. M.; Pedraz, S.; Reffert, S.; Sadegi, S.; Schweitzer, A.; Seifert, W.; Stahl, O.; Udry, S. (3 August 2018). "The CARMENES search for exoplanets around M dwarfs. A Neptune-mass planet traversing the habitable zone around HD 180617". arXiv:1808.01183 [astro-ph.EP].

- ↑ "HD 20794". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "HD 20794 f". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "HD 20794 g". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 581". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 581 d". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 581 f". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 581 g". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 625". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "HD 219134". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "HD 219134 e". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 667 C". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 667 C d". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 667 C h". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2016-02-23. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "Fomalhaut". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "Fomalhaut b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2014-04-26. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ "61 Vir". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "HD 192310". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 849". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 849 c". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 433". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 433 c". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2012-02-14. Archived from the original on 2014-02-10. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ "HD 102365". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "HD 285968". NASA Exoplanet Science Institute. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "GJ 176 c". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2010-12-17. Archived from the original on 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2014-05-20.

- ↑ Lee, Rhodi (2015-09-18). "Want To Name An Exoplanet? Here's Your Chance". Tech Times. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- ↑ "alf Cen B b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2011-05-27. Archived from the original on 2014-06-25. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ LePage, Andrew (2015-03-28). "Has Another Planet Been Found Orbiting Alpha Centauri B?". Drew Ex Machina. Archived from the original on 2015-09-29. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- ↑ "Lalande 21185 b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2017-02-14. Archived from the original on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- ↑ "GJ 15 A b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2016-08-07. Retrieved 2015-01-17.

- ↑ Trifonov, T; Kürster, M; Zechmeister, M; et al. (2018). "The CARMENES search for exoplanets around M dwarfs". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 609 (117): A117. arXiv:1710.01595. Bibcode:2018A&A...609A.117T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201731442.

- ↑ "eps Ind A b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2018-03-29. Archived from the original on 2018-05-11. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ Bartlett, Jennifer L; Ianna, Philip A; Begam, Michael C (2009). "A Search for Astrometric Companions to Stars in the Southern Hemisphere". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 121 (878): 365. Bibcode:2009PASP..121..365B. doi:10.1086/599044.

- ↑ "HD 26965 b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2018-01-15. Archived from the original on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- ↑ "GJ 682 b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ↑ "GJ 682 c". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ↑ "GJ 229 b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2014-05-25. Archived from the original on 2016-08-07. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- ↑ Barnes, J.R.; Jenkins, J. S.; Jones, H. R. A.; et al. (July 2012). "ROPS: A New Search for Habitable Earths in the Southern Sky". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 424 (1): 591–604. arXiv:1204.6283. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.424..591B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21236.x.

- ↑ Farihi, J.; Becklin, E. E.; Macintosh, B. A. (June 2004). "Mid-Infrared Observations of van Maanen 2: No Substellar Companion". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 608 (2): L109–L112. arXiv:astro-ph/0405245. Bibcode:2004ApJ...608L.109F. doi:10.1086/422502.

- ↑ Heinze, A. N.; Hinz, Philip M.; Sivanandam, Suresh; et al. (May 2010). "Constraints on Long-period Planets from an L'- and M-band Survey of Nearby Sun-like Stars: Observations". The Astrophysical Journal. 714 (2): 1551&ndash, 1569. arXiv:1003.5340. Bibcode:2010ApJ...714.1551H. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/714/2/1551.

- ↑ "VB 10 b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2015-09-29. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- ↑ Boss, Alan P.; Butler, R. Paul; Hubbard, William B.; et al. (2007). "Working Group on Extrasolar Planets". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 1 (T26A): 183. Bibcode:2007IAUTA..26..183B. doi:10.1017/S1743921306004509.

- ↑ "SCR 1845 b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2012-04-13. Archived from the original on 2015-10-01. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- ↑ "SDSS 141624 b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. 2010-01-18. Archived from the original on 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2014-05-20.

- ↑ "WISE 1217+16A b". The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Exoplanet.eu. Archived from the original on 2017-06-12. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ Clavin, Whitney; Harrington, J. D. (2014-04-25). "NASA's Spitzer and WISE Telescopes Find Close, Cold Neighbor of Sun". NASA. Archived from the original on 2014-04-26. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- ↑ Lucas, P. W.; Tinney, C. G.; Burningham, B.; et al. (2010). "The discovery of a very cool, very nearby brown dwarf in the Galactic plane". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 408 (1): L56–L60. arXiv:1004.0317. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.408L..56L. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2010.00927.x.

- ↑ Cushing, Michael C.; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Gelino, Christopher R.; et al. (2011). "The Discovery of Y Dwarfs using Data from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE)". The Astrophysical Journal. 743 (1): 50. arXiv:1108.4678. Bibcode:2011ApJ...743...50C. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/743/1/50.

- ↑ http://www.astronomy.com/news/2018/08/free-range-planet

- 1 2 Bortle, John E. (2001). "Light Pollution And Astronomy: The Bortle Dark-Sky Scale". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 2014-05-20.

- ↑ "HEC: Periodic Table of Exoplanets". Planetary Habitability Laboratory. University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. 2014-04-17. Archived from the original on 2014-07-03. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ Johnston, Robert (2014-11-02). "List of Nearby Stars: To 21 light years". Johnstonsarchive.net. Archived from the original on 2015-10-16. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- ↑ "epsilon Eridani". NameExoWorlds. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 2018-02-15. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- ↑ "Fomalhaut (alpha Piscis Austrini)". Nameexoworlds. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 2017-04-30. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- ↑ Cumming, Andrew; Butler, R. Paul; Marcy, Geoffrey W.; et al. (2008). "The Keck Planet Search: Detectability and the Minimum Mass and Orbital Period Distribution of Extrasolar Planets". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 120 (867): 531–554. arXiv:0803.3357. Bibcode:2008PASP..120..531C. doi:10.1086/588487.

External links

- "Extrasolar Planets". The Planetary Society. Planetary.org.

- "Extrasolar Planets News". Science Daily.

- "Exoplanet Exploration: Planets Beyond our Solar System". Exoplanet Exploration Program and Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. 2015-12-16.

- "Universe - Exoplanets (pictures, video, facts & news)". BBC.

- "PHL's Exoplanets Catalog". Planetary Habitability Laboratory. UPR Arecibo. 2018-03-02.

- Onsi Fakhouri. "Exoplanet Orbit Database". Exoplanet Data Explorer. Exoplanets.org.