Thiol

Thiol (/ˈθaɪɔːl/, /ˈθaɪɒl/)[1] is an organosulfur compound that contains a carbon-bonded sulfhydryl (R–SH) group (where R represents an alkyl or other organic substituent). Thiols are the sulfur analogue of alcohols (that is, sulfur takes the place of oxygen in the hydroxyl group of an alcohol), and the word is a portmanteau of "thion" + "alcohol," with the first word deriving from Greek θεῖον (theion) = "sulfur".[2] The –SH functional group itself is referred to as either a thiol group or a sulfhydryl group.

Many thiols have strong odors resembling that of garlic or rotten eggs. Thiols are used as odorants to assist in the detection of natural gas (which in pure form is odorless), and the "smell of natural gas" is due to the smell of the thiol used as the odorant. Thiols are sometimes referred to as mercaptans.[3][4] The term "mercaptan" /mərˈkæptæn/[5] was introduced in 1832 by William Christopher Zeise and is derived from the Latin mercurium captāns (capturing mercury)[6] because the thiolate group bonds very strongly with mercury compounds.[7]

Structure and bonding

Thiols and alcohols have similar connectivity. Because sulfur is a larger element than oxygen, the C–S bond lengths, typically around 180 picometers in length, is about 40 picometers longer than a typical C–O bond. The C–S–H angles approach 90° whereas the angle for the C-O-H group is more obtuse. In the solid or liquids, the hydrogen-bonding between individual thiol groups is weak, the main cohesive force being van der Waals interactions between the highly polarizable divalent sulfur centers.

The S-H bond is much weaker than the O-H bond as reflected in their respective bond dissociation energy (BDE). For CH3S-H, the BDE is 366 kJ/mol, while for CH3O-H, the BDE is 440 kJ/mol.[8]

Due to the small difference in the electronegativity of sulfur and hydrogen, an S–H bond is polar. In contrast, O-H bonds in hydroxyl groups are more polar. Thiols have a lower dipole moment relative to the corresponding alcohol.

Nomenclature

There are several ways to name the alkylthiols:

- The suffix -thiol is added to the name of the alkane. This method is nearly identical to naming an alcohol and is used by the IUPAC. Example: CH3SH would be methanethiol.

- The word mercaptan replaces alcohol in the name of the equivalent alcohol compound. Example: CH3SH would be methyl mercaptan, just as CH3OH is called methyl alcohol.

- The term sulfanyl or mercapto is used as a prefix. Example: mercaptopurine.

Physical properties

Odor

Many thiols have strong odors resembling that of garlic. The odors of thiols, particularly those of low molecular weight, are often strong and repulsive. The spray of skunks consists mainly of low-molecular-weight thiols and derivatives.[9][10][11][12][13] These compounds are detectable by the human nose at concentrations of only 10 parts per billion.[14] Human sweat contains (R)/(S)-3-methyl-3-sulfanylhexan-1-ol (MSH), detectable at 2 parts per billion and having a fruity, onion-like odor. (Methylthio)methanethiol (MeSCH2SH; MTMT) is a strong-smelling volatile thiol, also detectable at parts per billion levels, found in male mouse urine. Lawrence C. Katz and co-workers showed that MTMT functioned as a semiochemical, activating certain mouse olfactory sensory neurons, attracting female mice.[15] Copper has been shown to be required by a specific mouse olfactory receptor, MOR244-3, which is highly responsive to MTMT as well as to various other thiols and related compounds.[16] A human olfactory receptor, OR2T11, has been identified which, in the presence of copper, is highly responsive to the gas odorants (see below) ethanethiol and t-butyl mercaptan as well as other low molecular weight thiols, including allyl mercaptan found in human garlic breath, and the strong-smelling cyclic sulfide thietane.[17]

Thiols are also responsible for a class of wine faults caused by an unintended reaction between sulfur and yeast and the "skunky" odor of beer that has been exposed to ultraviolet light.

Not all thiols have unpleasant odors. For example, furan-2-ylmethanethiol contributes to the aroma of roasted coffee, whereas grapefruit mercaptan, a monoterpenoid thiol, is responsible for the characteristic scent of grapefruit. The effect of the latter compound is present only at low concentrations. The pure mercaptan has an unpleasant odor.

Natural gas distributors were required to add thiols, originally ethanethiol, to natural gas (which is naturally odorless) after the deadly New London School explosion in New London, Texas, in 1937. Many gas distributors were odorizing gas prior to this event. Most gas odorants utilized currently contain mixtures of mercaptans and sulfides, with t-butyl mercaptan as the main odor constituent in natural gas and ethanethiol in liquefied petroleum gas (LPG, propane).[18] In situations where thiols are used in commercial industry, such as liquid petroleum gas tankers and bulk handling systems, an oxidizing catalyst is used to destroy the odor. A copper-based oxidation catalyst neutralizes the volatile thiols and transforms them into inert products.

Boiling points and solubility

Thiols show little association by hydrogen bonding, both with water molecules and among themselves. Hence, they have lower boiling points and are less soluble in water and other polar solvents than alcohols of similar molecular weight. For this reason also, thiols and corresponding thioether functional group isomers have similar solubility characteristics and boiling points, whereas the same is not true of alcohols and their corresponding isomeric ethers.

Bonding

The S-H bond in thiols is weak compared to the O-H bond in alcohols. For CH3X-H, the bond enthalpies are 365.07 (+/-2.1) for X = S and 440.2 (+/-3) kcal/mol for X = O.[19] H-atom abstraction from a thiol gives a thiyl radical with the formula RS., where R = alkyl or aryl.

Characterization

Volatile thiols are easily and almost unerringly detected by their distinctive odor. S-specific analyzers for gas chromatographs are useful. Spectroscopic indicators are the D2O-exchangeable SH signal in the 1H NMR spectrum (33S is NMR-active but signals for divalent sulfur are very broad and of little utility[20]). The νSH band appears near 2400 cm−1 in the IR spectrum.[3] In the nitroprusside reaction, free thiol groups react with sodium nitroprusside and ammonium hydroxide to give a red colour.

Preparation

In industry, methanethiol is prepared by the reaction of hydrogen sulfide with methanol. This method is employed for the industrial synthesis of methanethiol:

- CH3OH + H2S → CH3SH + H2O

Such reactions are conducted in the presence of acidic catalysts. The other principal route to thiols involves the addition of hydrogen sulfide to alkenes. Such reactions are usually conducted in the presence of an acid catalyst or UV light. Halide displacement, using the suitable organic halide and sodium hydrogen sulfide has also been utilized.[21]

Another method entails the alkylation of sodium hydrosulfide.

- RX + NaSH → RSH + NaX (X = Cl, Br, I)

This method is used for the production of thioglycolic acid from chloroacetic acid.

Laboratory methods

In general, on the typical laboratory scale, the direct reaction of a halogenoalkane with sodium hydrosulfide is inefficient owing to the competing formation of thioethers Instead, alkyl halides are converted to thiols via a S-alkylation of thiourea. This multistep, one-pot process proceeds via the intermediacy of the isothiouronium salt, which is hydrolyzed in a separate step:[22]

- CH3CH2Br + SC(NH2)2 → [CH3CH2SC(NH2)2]Br

- [CH3CH2SC(NH2)2]Br + NaOH → CH3CH2SH + OC(NH2)2 + NaBr

The thiourea route works well with primary halides, especially activated ones. Secondary and tertiary thiols are less easily prepared. Secondary thiols can be prepared from the ketone via the corresponding dithioketals.[23] A related two-step process involves alkylation of thiosulfate to give the thiosulfonate ("Bunte salt"), followed by hydrolysis. The method is illustrated by one synthesis of thioglycolic acid:

- ClCH2CO2H + Na2S2O3 → Na[O3S2CH2CO2H] + NaCl

- Na[O3S2CH2CO2H] + H2O → HSCH2CO2H + NaHSO4

Organolithium compounds and Grignard reagents react with sulfur to give the thiolates, which are readily hydrolyzed:[24]

- RLi + S → RSLi

- RSLi + HCl → RSH + LiCl

Phenols can be converted to the thiophenols via rearrangement of their O-aryl dialkylthiocarbamates.[25]

Many thiols are prepared by reductive dealkylation of thioethers, especially benzyl derivatives and thioacetals.[26]

Reactions

Akin to the chemistry of alcohols, thiols form thioethers, thioacetals, and thioesters, which are analogous to ethers, acetals, and esters respectively. Thiols and alcohols are also very different in their reactivity, thiols being more easily oxidized than alcohols. Thiolates are more potent nucleophiles than the corresponding alkoxides.

S-alkylation

Thiols, or more specific their conjugate bases, are readily alkylated to give thioethers:

- RSH + R′Br + B → RSR′ + [HB]Br (B = base)

S-arylation

Thiophenols are produced by S-arylation or the replacement of diazonium leaving group with sulfhydryl anion (SH−):

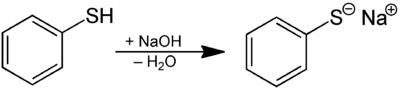

Acidity

Relative to the alcohols, thiols are more acidic. The conjugate base of a thiol is called a thiolate. Butanethiol has a pKa of 10.5 vs 15 for butanol. Thiophenol has a pKa of 6 vs 10 for phenol. A highly acidic thiol is pentafluorothiophenol (C6F5SH) with a pKa of 2.68. Thus, thiolates can be obtained from thiols by treatment with alkali metal hydroxides.

Redox

Thiols, especially in the presence of base, are readily oxidized by reagents such as iodine to give an organic disulfide (R–S–S–R).

- 2 R–SH + Br2 → R–S–S–R + 2 HBr

Oxidation by more powerful reagents such as sodium hypochlorite or hydrogen peroxide can also yield sulfonic acids (RSO3H).

- R–SH + 3 H2O2 → RSO3H + 3 H2O

Oxidation can also be effected by oxygen in the presence of catalysts:[29]

- 2 R–SH + 1⁄2 O2 → RS–SR + H2O

Thiols participate in thiol-disulfide exchange:

- RS–SR + 2 R′SH → 2 RSH + R′S–SR′

This reaction is important in nature.

Metal ion complexation

With metal ions, thiolates behave as ligands to form transition metal thiolate complexes. The term mercaptan is derived from the Latin mercurium captans (capturing mercury)[6] because the thiolate group bonds so strongly with mercury compounds. According to hard/soft acid/base (HSAB) theory, sulfur is a relatively soft (polarizable) atom. This explains the tendency of thiols to bind to soft elements/ions such as mercury, lead, or cadmium. The stability of metal thiolates parallels that of the corresponding sulfide minerals.

Thioxanthates

Thiolates react with carbon disulfide to give thioxanthate (RSCS−

2).

Thiyl radicals

Free radicals derived from mercaptans, called thiyl radicals, are commonly invoked to explain reactions in organic chemistry and biochemistry. They have the formula RS• where R is an organic substituent such as alkyl or aryl.[4] They arise from or can be generated by a number of routes, but the principal method is H-atom abstraction from thiols. Another method involves homolysis of organic disulfides.[30] In biology thiyl radicals are responsible for the formation of the deoxyribonucleic acids, building blocks for DNA. This conversion is catalysed by ribonucleotide reductase (see figure).[31] Thiyl intermediates also are produced by the oxidation of glutathione, an antioxidant in biology. Thiyl radicals (sulfur-centred) can transform to carbon-centred radicals via hydrogen atom exchange equilibria. The formation of carbon-centred radicals could lead to protein damage via the formation of C–C bonds or backbone fragmentation.[32]

Biological importance

Cysteine and cystine

As the functional group of the amino acid cysteine, the thiol group plays a very important role in biology. When the thiol groups of two cysteine residues (as in monomers or constituent units) are brought near each other in the course of protein folding, an oxidation reaction can generate a cystine unit with a disulfide bond (–S–S–). Disulfide bonds can contribute to a protein's tertiary structure if the cysteines are part of the same peptide chain, or contribute to the quaternary structure of multi-unit proteins by forming fairly strong covalent bonds between different peptide chains. A physical manifestation of cysteine-cystine equilibrium is provided by hair straightening technologies.[33]

Sulfhydryl groups in the active site of an enzyme can form noncovalent bonds with the enzyme's substrate as well, contributing to covalent catalytic activity in catalytic triads. Active site cysteine residues are the functional unit in cysteine protease catalytic triads. Cysteine residues may also react with heavy metal ions (Zn2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, Ag+) because of the high affinity between the soft sulfide and the soft metal (see hard and soft acids and bases). This can deform and inactivate the protein, and is one mechanism of heavy metal poisoning.

Cofactors

Many cofactors (non-protein-based helper molecules) feature thiols. The biosynthesis and degradation of fatty acids and related long-chain hydrocarbons is conducted on a scaffold that anchors the growing chain through a thioester derived from the thiol Coenzyme A. The biosynthesis of methane, the principal hydrocarbon on Earth, arises from the reaction mediated by coenzyme M, 2-mercaptoethyl sulfonic acid. Thiolates, the conjugate bases derived from thiols, form strong complexes with many metal ions, especially those classified as soft. The stability of metal thiolates parallels that of the corresponding sulfide minerals.

In skunks

The spray of skunks consists mainly of low-molecular-weight thiols and derivatives. These have a foul odor that protects skunks from predators such as humans and wolves. Owls can prey on skunks as they do not have a sense of smell[34] and are therefore not deterred.

Examples of thiols

- Methanethiol – CH3SH [methyl mercaptan]

- Ethanethiol – C2H5SH [ethyl mercaptan]

- 1-Propanethiol – C3H7SH [n-propyl mercaptan]

- 2-Propanethiol – CH3CH(SH)CH3 [2C3 mercaptan]

- Allyl mercaptan – CH2=CHCH2SH [2-propenethiol]

- Butanethiol – C4H9SH [n-butyl mercaptan]

- tert-Butyl mercaptan – (CH3)3CSH [t-butyl mercaptan]

- Pentanethiols – C5H11SH [pentyl mercaptan]

- Thiophenol – C6H5SH

- Dimercaptosuccinic acid

- Thioacetic acid

- Coenzyme A

- Glutathione

- Metallothionein

- Cysteine

- 2-Mercaptoethanol

- Dithiothreitol/dithioerythritol (an epimeric pair)

- 2-Mercaptoindole

- Grapefruit mercaptan

- Furan-2-ylmethanethiol

- 3-Mercaptopropane-1,2-diol

- 3-Mercapto-1-propanesulfonic acid

- 1-Hexadecanethiol

- Pentachlorobenzenethiol

See also

Footnotes

References

- ↑ Dictionary Reference: thiol Archived 2013-04-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ θεῖον Archived 2017-05-10 at the Wayback Machine., Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon

- 1 2 Patai, Saul, ed. (1974). The chemistry of the thiol group. London: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-66949-0.

- 1 2 R. J. Cremlyn (1996). An Introduction to Organosulfur Chemistry. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-95512-4.

- ↑ Dictionary Reference: mercaptan Archived 2012-11-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Oxford American Dictionaries (Mac OS X Leopard).

- ↑ "Mercaptan" (ethyl thiol) was discovered in 1834 by the Danish professor of chemistry William Christopher Zeise (1789–1847). He called it "mercaptan", a contraction of "corpus mercurium captans" (mercury-capturing substance) [p. 88], because it reacted violently with mercury(II) oxide ("deutoxide de mercure") [p. 92]. See:

- Zeise, William Christopher (1834). "Sur le mercaptan; avec des observations sur d'autres produits resultant de l'action des sulfovinates ainsi que de l'huile de vin, sur des sulfures metalliques" [On mercaptan; with observations on other products resulting from the action of sulfovinates [typically, ethyl hydrogen sulfate] and oil of wine [a mixture of diethylsufate and ethylene polymers] on metal sulfides]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 56: 87–97. Archived from the original on 2015-03-20.

- The article in Annales de Chimie et de Physique (1834) was translated from the German article: Zeise, W. C. (1834). "Das Mercaptan, nebst Bemerkungen über einige neue Producte aus der Einwirkung der Sulfurete auf weinschwefelsaure Salze und auf das Weinöl". Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 107 (27): 369–431. Bibcode:1834AnP...107..369Z. doi:10.1002/andp.18341072402. Archived from the original on 2015-03-20.

- The article in Annalen der Physik und Chemie (1834) was translated from the original Danish article in: Zeise (1834). "Mercaptanet med Bemærkninger over nogle andre nye Producter af Svovelvinsyre saltene, som og af den tunge Vinolle, ved Sulfureter". Kongelige Danske Videnskabers Selskabs Skrifter (Special issue): 1–70.

- German translation is reprinted in:Zeise, W. C. (1834). "Das Mercaptan, nebst Bemerkungen über einige andere neue Erzeugnisse der Wirkung schwefelweinsaurer Salze, wie auch des schweren Weinöls auf Sulphurete". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 1 (1): 257–268, 345–356, 396–413, 457–475. doi:10.1002/prac.18340010154.

- Summarized in: Zeise, W. C. (1834). "Ueber das Mercaptan" [On mercaptan]. Annalen der Pharmacie. 11 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1002/jlac.18340110102. Archived from the original on 2015-03-20.

- ↑ Lide, David R., ed. (2006). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0487-3.

- ↑ Andersen K. K.; Bernstein D. T. (1978). "Some Chemical Constituents of the Scent of the Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis)". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 1 (4): 493–499. doi:10.1007/BF00988589.

- ↑ Andersen K. K., Bernstein D. T.; Bernstein (1978). "1-Butanethiol and the Striped Skunk". Journal of Chemical Education. 55 (3): 159–160. Bibcode:1978JChEd..55..159A. doi:10.1021/ed055p159.

- ↑ Andersen K. K.; Bernstein D. T.; Caret R. L.; Romanczyk L. J., Jr. (1982). "Chemical Constituents of the Defensive Secretion of the Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis)". Tetrahedron. 38 (13): 1965–1970. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(82)80046-X.

- ↑ Wood W. F.; Sollers B. G.; Dragoo G. A.; Dragoo J. W. (2002). "Volatile Components in Defensive Spray of the Hooded Skunk, Mephitis macroura". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 28 (9): 1865–70. doi:10.1023/A:1020573404341. PMID 12449512.

- ↑ William F. Wood. "Chemistry of Skunk Spray". Dept. of Chemistry, Humboldt State University. Archived from the original on October 8, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2008.

- ↑ Aldrich, T.B. (1896). "A Chemical Study of the Secretion of the Anal Glands of Mephitis mephitiga (Common Skunk), with Remarks on the Physiological Properties of This Secretion". J. Exp. Med. 1 (2): 323–340. doi:10.1084/jem.1.2.323. PMC 2117909. PMID 19866801.

- ↑ Lin, DaYu; Zhang, Shaozhong; Block, Eric; Katz, Lawrence C (2005). "Encoding social signals in the mouse main olfactory bulb". Nature. 434: 470–477. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..470L. doi:10.1038/nature03414. PMID 15724148.

- ↑ Duan, Xufang; Block, Eric; Li, Zhen; Connelly, Timothy; Zhang, Jian; Huang, Zhimin; Su, Xubo; Pan, Yi; et al. (2012). "Crucial role of copper in detection of metal-coordinating odorants". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109: 3492–3497. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.3492D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1111297109. PMC 3295281. PMID 22328155.

- ↑ "Copper key to our sensitivity to rotten eggs' foul smell". chemistryworld.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ↑ Roberts, JS, ed. (1997). Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.

- ↑ Luo, Y.-R.; Cheng, J.-P. (2017). "Bond Dissociation Energies". In J. R. Rumble. Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. CRC Press.

- ↑ Man, Pascal P. "Sulfur-33 NMR references". www.pascal-man.com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ↑ John S Roberts, "Thiols", in Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 1997, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/0471238961.2008091518150205.a01

- ↑ Speziale, A. J. (1963). "Ethanedithiol". Organic Syntheses. ; Collective Volume, 4, p. 401 .

- ↑ S. R. Wilson, G. M. Georgiadis (1990). "Mecaptans from Thioketals: Cyclododecyl Mercaptan". Organic Syntheses. ; Collective Volume, 7, p. 124 .

- ↑ E. Jones and I. M. Moodie (1990). "2-Thiophenethiol". Organic Syntheses. ; Collective Volume, 6, p. 979 .

- ↑ Melvin S. Newman and Frederick W. Hetzel (1990). "Thiophenols from Phenols: 2-Naphthalenethiol". Organic Syntheses. ; Collective Volume, 6, p. 824 .

- ↑ Ernest L. Eliel, Joseph E. Lynch, Fumitaka Kume, and Stephen V. Frye (1993). "Chiral 1,3-oxathiane from (+)-Pulegone: Hexahydro-4,4,7-trimethyl-4H-1,3-benzoxathiin". Organic Syntheses. ; Collective Volume, 8, p. 302

- ↑ "Novel One-Pot Synthesis of Thiophenols from Related Triazenes under Mild Conditions". Synlett. 23: 1893–1896. 2012. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1316557.

- ↑ Leuckart R. (189). "Eine neue Methode zur Darstellung aromatischer Mercaptane". J. Prakt. Chem. 41: 179. doi:10.1002/prac.18900410114.

- ↑ Akhmadullina, A. G.; Kizhaev, B. V.; Nurgalieva, G. M.; Khrushcheva, I. K.; Shabaeva, A. S.; et al. (1993). "Heterogeneous catalytic demercaptization of light hydrocarbon feedstock". Chemistry and Technology of Fuels and Oils. 29 (3): 108–109. doi:10.1007/bf00728009. Archived from the original on 2011-08-15.

- ↑ Kathrin-Maria Roy "Thiols and Organic sulphides" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2002, Wiley-VCH Verlag, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a26_767

- ↑ Stubbe, JoAnne; Nocera, Daniel G.; Yee, Cyril S.; Chang, Michelle C. Y. (2003). "Radical Initiation in the Class I Ribonucleotide Reductase: Long-Range Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer?". Chem. Rev. 103 (6): 2167–2202. doi:10.1021/cr020421u.

- ↑ Hofstetter, Dustin; Nauser, Thomas; Koppenol, Willem H. (2010). "Hydrogen Exchange Equilibria in Glutathione Radicals: Rate Constants". Chem. Res. Toxicol. 23 (10): 1596–1600. doi:10.1021/tx100185k.

- ↑ Reece, Urry; et al. (2011). Campbell Biology (Ninth ed.). New York: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. pp. 65, 83.

- ↑ "Understanding Owls - The Owls Trust". theowlstrust.org. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

External links

- Mercaptans (or Thiols) at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- Applications, Properties, and Synthesis of ω-Functionalized n-Alkanethiols and Disulfides – the Building Blocks of Self-Assembled Monolayers by D. Witt, R. Klajn, P. Barski, B.A. Grzybowski at Northwestern University.

- Mercaptan, by The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia.

- What is Mercaptan?, by Columbia Gas of Pennsylvania and Maryland.

- What Is the Worst Smelling Chemical?, by About Chemistry.