Sodium nitroprusside

| |

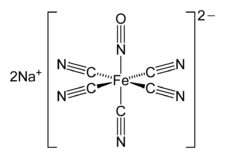

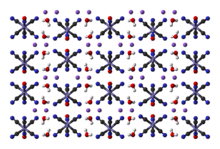

Idealized depiction of this compound (top), and a picture of a sample (bottom). | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Nipride, Nitropress, others |

| Synonyms | SNP |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% (intravenous) |

| Metabolism | By haemoglobin being converted to cyanmethaemoglobin and cyanide ions |

| Onset of action | nearly immediate[1] |

| Elimination half-life | <2 minutes (3 days for thiocyanate metabolite) |

| Duration of action | 1 to 10 minutes[1] |

| Excretion | kidney (100%; as thiocyanate)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C5FeN6Na2O |

| Molar mass | 261.918 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.72 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | 100 mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

Sodium nitroprusside (SNP), sold under the brand name Nitropress among others, is a medication used to lower blood pressure.[1] This may be done if the blood pressure is very high and resulting in symptoms, in certain types of heart failure, and during surgery to decrease bleeding.[1] It is used by continuous injection into a vein.[1] Onset is typically immediate and effects last for up to ten minutes.[1]

Common side effects include low blood pressure and cyanide toxicity.[1] Other serious side effects include methemoglobinemia.[1] It is not generally recommended during pregnancy due to concerns of side effects.[3] High doses are not recommended for more than ten minutes.[4] It works by causing the dilation of blood vessels.[1]

Sodium nitroprusside was discovered as early as 1850 and found to be useful in medicine in 1928.[5][6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[7] In the United States a course of treatment costs less than 25 USD.[8]

Medical use

Sodium nitroprusside is intravenously infused in cases of acute hypertensive crises.[9][10] Its effects are usually seen within a few minutes.[2]

Nitric oxide reduces both total peripheral resistance and venous return, thus decreasing both preload and afterload. So, it can be used in severe congestive heart failure where this combination of effects can act to increase cardiac output. In situations where cardiac output is normal, the effect is to reduce blood pressure.[9][11] It is sometimes also used to induce hypotension (to reduce bleeding) for surgical procedures (for which it is also FDA, TGA, and MHRA labelled).[9][10][12]

This compound has also been used as a treatment for aortic valve stenosis,[13] oesophageal varices,[14] myocardial infarction,[15] pulmonary hypertension,[16][17][18] respiratory distress syndrome in the newborn,[19][20] shock,[20] and ergot toxicity.[21]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects by incidence and severity[9][11][22]

Common

- Bradyarrhythmia (low heart rate)

- Hypotension (low blood pressure)

- Palpitations

- Tachyarrhythmia (high heart rate)

- Apprehension

- Restlessness

- Confusion

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Somnolence

- Rash

- Sweating

- Thyroid suppression

- Muscle twitch

- Oliguria

- Renal azotemia

Unknown frequency

- Nausea

- Retching

- Anxiety

- Chest discomfort

- Paraesthesial warmth

- Abdominal pain

- Orthostatic hypotension

- ECG changes

- Skin irritation

- Flushing

- Injection site erythema

- Injection site streaking

Serious

- Ileus

- Reduced platelet aggregation

- Haemorrhage

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Metabolic acidosis

- Methaemoglobinaemia

- Cyanide poisoning

- Thiocyanate toxicity

Contraindications

Sodium nitroprusside should not be used for compensatory hypertension (e.g. due to an anteriovenous stent or coarctation of the aorta).[11] It should not be used in patients with inadequate cerebral circulation or in patients who are near death. It should not be used in patients with vitamin B12 deficiency, anaemia, severe renal disease, or hypovolaemia.[11] Patients with conditions associated with a higher cyanide/thiocyanate ratio (e.g. congenital (Leber's) optic atrophy, tobacco amblyopia) should only be treated with sodium nitroprusside with great caution.[11] Its use in patients with acute congestive heart failure associated with reduced peripheral resistance is also not recommended.[11] Its use in hepatically impaired individuals is also not recommended, as is its use in cases of pre-existing hypothyroidism.[9]

Its use in pregnant women is advised against, although the available evidence suggests it may be safe, provided maternal pH and cyanide levels are closely monitored.[11][23] Some evidence suggests sodium nitroprusside use in critically ill children may be safe, even without monitoring of cyanide level.[24]

Interactions

The only known drug interactions are pharmacodynamic in nature, that is it is possible for other antihypertensive drugs to reduce the threshold for dangerous hypotensive effects to be seen.[11]

Overdose

Due to its cyanogenic nature, overdose may be particularly dangerous. Treatment of sodium nitroprusside overdose includes the following:[11][25]

- Discontinuing sodium nitroprusside administration

- Buffering the cyanide by using sodium nitrite to convert haemoglobin to methaemoglobin as much as the patient can safely tolerate

- Infusing sodium thiosulfate to convert the cyanide to thiocyanate.

Haemodialysis is ineffective for removing cyanide from the body but it can be used to remove most of the thiocyanate produced from the above procedure.[11]

Toxicology

The cyanide can be detoxified by reaction with a sulfur-donor such as thiosulfate, catalysed by the enzyme rhodanese.[26] In the absence of sufficient thiosulfate, cyanide ions can quickly reach toxic levels.[26]

| Species | LD50 (mg/kg) for oral administration[27] | LD50 (mg/kg) for IV administration[11] | LD50 (mg/kg) for skin administration[27] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | 43 | 8.4 | ? |

| Rat | 300 | 11.2 | >2000 |

| Rabbit | ? | 2.8 | ? |

| Dog | ? | 5 | ? |

Mechanism of action

Sodium nitroprusside has potent vasodilating effects in arterioles and venules (arterioles more than venules, but this selectivity is much less marked than that of nitroglycerin, which acts preferentially at venous smooth muscle) as a result of its breakdown to nitric oxide (NO).[9][11][22]

Sodium nitroprusside breaks down in circulation to release nitric oxide (NO).[5] It does this by binding to oxyhaemoglobin to release cyanide, methaemoglobin and nitric oxide.[5] NO activates guanylate cyclase in vascular smooth muscle and increases intracellular production of cGMP. cGMP activates protein kinase G which activates phosphatases which inactivate myosin light chains.[28] Myosin light chains are involved in muscle contraction. The end result is vascular smooth muscle relaxation, which allow vessels to dilate.[28] This mechanism is similar to that of phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors such as sildenafil (Viagra) and tadalafil (Cialis), which elevate cGMP concentration by inhibiting its degradation by PDE5.[29]

A role for NO in various common psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia,[30][31][32][33] bipolar disorder[34][35][36] and major depressive disorder[37][38][39] has been proposed and supported by several clinical findings. These findings may also implicate the potential of drugs that alter NO signalling such as SNP in their treatment.[32][38] Such a role is also supported by the findings of the recent SNP clinical trial.[40]

Structure and properties

Nitroprusside is an inorganic compound with the formula Na2[Fe(CN)5NO], usually encountered as the dihydrate, Na2[Fe(CN)5NO]·2H2O.[41] This red-colored sodium salt dissolves in water or ethanol to give solutions containing the free complex dianion [Fe(CN)5NO]2−.

Nitroprusside is a complex anion that features an octahedral iron(III) centre surrounded by five tightly bound cyanide ligands and one linear nitric oxide ligand (Fe-N-O angle = 176.2 °[42]). The anion possesses idealized C4vsymmetry.

Nitric oxide is a non-innocent ligand. Due to the linear Fe-N-O angle, the relatively short N-O distance of 113 pm[42] and the relatively high stretching frequency of 1947 cm−1, the complex is formulated as containing an NO+ ligand.[43] Consequently, iron is assigned an oxidation state of 2+. The iron center has a diamagnetic low-spin d6 electron configuration, although a paramagnetic long-lived metastable state has been observed by EPR spectroscopy.[44]

The chemical reactions of sodium nitroprusside are mainly associated with the NO ligand.[45] For example, addition of S2− ion to [Fe(CN)5(NO)]2− produces the violet colour[Fe(CN)5(NOS)]4− ion, which is the basis for a sensitive test for S2− ions. An analogous reaction also exists with OH− ions, giving [Fe(CN)5(NO2)]4−.[43] Roussin's red salt (K2[Fe2S2(NO)4]) and Roussin's black salt (NaFe4S3(NO)7) are related iron nitrosyl complexes. The former was first prepared by treating nitroprusside with sulfur.[46]

This compound decomposes to sodium ferrous ferrocyanide, sodium ferrocyanide, nitric oxide, and cyanogen at about 450 °C. It decomposes in aqueous acid to liberate hydrocyanic acid (HCN).[47] Shielded from light, the concentrated solution is stable for more than two years at room temperature. It breaks down rapidly upon exposure to light, although the details are poorly understood. It degrades when heated (e.g. by sterilization in an autoclave), but addition of citric acid is helpful.[48]

Preparation

Sodium nitroprusside can be synthesized by digesting a solution of potassium ferrocyanide in water with nitric acid, followed by neutralization with sodium carbonate:[49]

- K4[Fe(CN)6] + 6 HNO3 → H2[Fe(CN)5(NO)] + CO2 + NH4NO3 + 4 KNO3

- H2[Fe(CN)5NO] + Na2CO3 → Na2[Fe(CN)5(NO)] + CO2 + H2O

Alternatively, ferrocyanide may be oxidized with nitrite as well:[43]

- [Fe(CN)6]4− + H2O + NO2− → [Fe(CN)5(NO)]2− + CN− + 2 OH−

Other uses

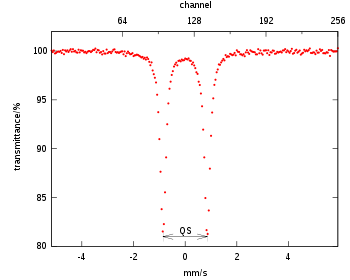

Sodium nitroprusside is often used as a reference compound for the calibration of Mössbauer spectrometers.[47] Sodium nitroprusside crystals are also of interest for optical storage. For this application, sodium nitroprusside can be reversibly promoted to a metastable excited state by blue-green light, and de-excited by heat or red light.[50]

In physiology research, sodium nitroprusside is frequently used to test endothelium-independent vasodilation. Iontophoresis, for example, allows local administration of the drug, preventing the systemic effects listed above but still inducing local microvascular vasodilation. Sodium nitroprusside is also used in microbiology, where it has been linked with the dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms by acting as a nitric oxide donor.[51][52]

Analytical reagent

Sodium nitroprusside is also used as an analytical reagent under the name sodium nitroferricyanide for the detection of methyl ketones, and for the detection of amines that are often found in illicit drugs. Sodium nitroprusside was found to give a reaction with acetone or creatine under basic conditions in 1882. Rothera refined this method by the use of ammonia in place of sodium or potassium hydroxide. The reaction was now specific for methyl ketones. Addition of ammonium salts (e.g. ammonium sulfate) improved the sensitivity of the test, too.[53]

In this test, known as Rothera's test, methyl ketones (CH3C(=O)-) under alkaline conditions give bright red coloration (see also iodoform test). Rothera's test was initially applied to detecting ketonuria (a symptom of diabetes) in urine samples. This reaction is now exploited in the form of urine test strips (e.g. "Ketostix").[54]

Sodium nitroprusside is used in a separate urinalysis test known as the cyanide nitroprusside test or Brand's test. In this test, sodium cyanide is added first to urine and let stand for about 10 minutes. In this time, disulfide bonds will be broken by the released cyanide. The destruction of disulfide bonds liberates cysteine from cystine as well as homocysteine from homocystine. Next, sodium nitroprusside is added to the solution and it reacts with the newly freed sulfhydryl groups. The test will turn a red/purple colour if the test is positive, indicating significant amounts of amino acids were in the urine (aminoaciduria). Cysteine, cystine, homocysteine, and homocystine all react when present in the urine when this test is performed. This test can indicate inborn errors of amino acid transporters such as cystinuria, which results from pathology in the transport of dibasic amino acids.[55]

Sodium nitroprusside is also able to detect amines. This compound is thus used as a stain to indicate amines in thin layer chromatography.[56] Sodium nitroprusside is similarly used as a presumptive test for the presence of alkaloids (amine-containing natural products) common in illicit substances.[57] The test, called Simon's test, is performed by adding 1 volume of a solution of sodium nitroprusside and acetaldehyde in deionized water to a suspected drug, followed by the addition of 2 volumes of an aqueous sodium carbonate solution. The test turns blue for some secondary amines. The most common secondary amines encountered in forensic chemistry include 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, the main component in Ecstasy) and phenethylamines such as methamphetamine. Sodium nitroprusside is also useful in the identification the mercaptans (thiol groups) in the nitroprusside reaction.

History

Sodium nitroprusside is primarily used as a vasodilator. It was first used in human medicine in 1928.[5] By 1955, data on its safety during short-term use in people with severe hypertension had become available.[5] Despite this, due to difficulties in its chemical preparation, it was not finally approved by the US FDA until 1974 for the treatment of severe hypertension.[5] By 1993, its popularity had grown such that total sales in the US had totalled US$2 million.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Sodium Nitroprusside". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 Brunton, L; Chabner, B; Knollman, B (2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ↑ "Nitroprusside (Nitropress) Use During Pregnancy". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ WHO Model Formulary 2008 (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. p. 283. ISBN 9789241547659. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Friederich, JA; Butterworth, JF 4th (July 1995). "Sodium Nitroprusside: Twenty Years and Counting". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 81 (1): 152–162. doi:10.1213/00000539-199507000-00031. PMID 7598246. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Nichols, David G.; Greeley, William J.; Lappe, Dorothy G.; Ungerleider, Ross M.; Cameron, Duke E.; Spevak, Philip J.; Wetzel, Randall C. (2006). Critical Heart Disease in Infants and Children (2 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 192. ISBN 9780323070072.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 146. ISBN 9781284057560.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "NITROPRESS (sodium nitroprusside) injection, solution, concentrate [Hospira, Inc.]". DailyMed. Hospira, Inc. January 2011. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- 1 2 Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65th ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "DBL® SODIUM NITROPRUSSIDE FOR INJECTION BP" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Hospira Australia Pty Ltd. 22 April 2010. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ↑ Ikram, H; Low, CJ; Crozier, IG; Shirlaw, T (February 1992). "Hemodynamic effects of nitroprusside on valvular aortic stenosis". The American Journal of Cardiology. 69 (4): 361–366. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(92)90234-P. PMID 1734649.

- ↑ Sirinek, KR; Adcock, DK; Levine, BA (January 1989). "Simultaneous infusion of nitroglycerin and nitroprusside to offset adverse effects of vasopressin during portosystemic shunting". American Journal of Surgery. 157 (1): 33–37. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(89)90416-9. PMID 2491934.

- ↑ Yusuf, S; Collins, R; MacMahon, S; Peto, R (May 1988). "Effect of intravenous nitrates on mortality in acute myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomised trials". Lancet. 1 (8594): 1088–92. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(88)91906-X. PMID 2896919.

- ↑ Costard-Jäckle, A; Fowler, MB (January 1992). "Influence of preoperative pulmonary artery pressure on mortality after heart transplantation: testing of potential reversibility of pulmonary hypertension with nitroprusside is useful in defining a high risk group". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 19 (1): 48–54. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(92)90050-W. PMID 1729345.

- ↑ Knapp, E; Gmeiner, R (February 1977). "Reduction of pulmonary hypertension by nitroprusside". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmacy. 15 (2): 75–80. PMID 885667.

- ↑ Freitas, AF Jr; Bacal, F; Oliveira Júnior Jde, L; Fiorelli, AI; Santos, RH; Moreira, LF; Silva, CP; Mangini, S; Tsutsui, JM; Bocchi, EA (September 2012). "Sildenafil vs. sodium before nitroprusside for the pulmonary hypertension reversibility test before cardiac transplantation". Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 99 (3): 848–56. doi:10.1590/S0066-782X2012005000076. PMID 22898992.

- ↑ Palhares, DB; Figueiredo, CS; Moura, AJ (January 1998). "Endotracheal inhalatory sodium nitroprusside in severely hypoxic newborns". Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 26 (3): 219–224. doi:10.1515/jpme.1998.26.3.219. PMID 9773383.

- 1 2 Benitz, WE; Malachowski, N; Cohen, RS; Stevenson, DK; Ariagno, RL; Sunshine, P (January 1985). "Use of sodium nitroprusside in neonates: efficacy and safety". The Journal of Pediatrics. 106 (1): 102–110. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(85)80477-7. PMID 3917495.

- ↑ Merhoff, GC; Porter, JM (November 1974). "Ergot intoxication: historical review and description of unusual clinical manifestations". Annals of Surgery. 180 (5): 773–779. doi:10.1097/00000658-197411000-00011. PMC 1343691. PMID 4371616.

- 1 2 "nitroprusside sodium (Rx) - Nipride, Nitropress, more." Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Sass, N; Itamoto, CH; Silva, MP; Torloni, MR; Atallah, AN (March 2007). "Does sodium nitroprusside kill babies? A systematic review". Sao Paulo Medical Journal. 125 (2): 108–111. doi:10.1590/S1516-31802007000200008. PMID 17625709. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014.

- ↑ Thomas, C; Svehla, L; Moffett, BS (September 2009). "Sodium nitroprusside induced cyanide toxicity in pediatric patients". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 8 (5): 599–602. doi:10.1517/14740330903081717. PMID 19645589.

- ↑ Rindone, JP; Sloane, EP (April 1992). "Cyanide toxicity from sodium nitroprusside: Risks and management". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 26 (4): 515–519. doi:10.1177/106002809202600413. PMID 1533553.

- 1 2 "Nitropress (Nitroprusside Sodium) Drug Information: Clinical Pharmacology - Prescribing Information at RxList". RxList. RxList Inc. 4 July 2009. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- 1 2 "Material Safety Data Sheet Sodium nitroprusside, ACS" (PDF). Qorpak. Berlin Packaging. 1 August 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- 1 2 Murad, F (July 1986). "Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate as a Mediator of Vasodilation" (PDF). The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 78 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1172/JCI112536. PMC 329522. PMID 2873150. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Kukreja, RC; Salloum, FN; Das, A (May 2012). "Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate Signaling and Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibitors in Cardioprotection" (PDF). Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 59 (22): 1921–1927. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.086. PMC 4230443. PMID 22624832. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Bernstein, HG; Bogerts, B; Keilhoff, G (Oct 2005). "The many faces of nitric oxide in schizophrenia. A review". Schizophrenia Research. 78 (1): 69–86. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.019. PMID 16005189.

- ↑ Silberberg, G; Ben-Shachar, D; Navon, R (October 2010). "Genetic analysis of nitric oxide synthase 1 variants in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B. 153B (7): 1318–1328. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.31112. PMID 20645313.

- 1 2 Bernstein, HG; Keilhoff, G; Steiner, J; Dobrowolny, H; Bogerts, B (November 2011). "Nitric oxide and schizophrenia: present knowledge and emerging concepts of therapy". CNS & Neurological Disorders - Drug Targets. 10 (7): 792–807. doi:10.2174/187152711798072392. PMID 21999729.

- ↑ Coyle, JT (July 2013). "Nitric Oxide and Symptom Reduction in Schizophrenia". JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (7): 664–665. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.210. PMID 23699799.

- ↑ Yanik, M; Vural, H; Tutkun, H; Zoroğlu, SS; Savaş, HA; Herken, H; Koçyiğit, A; Keleş, H; Akyol, O (February 2004). "The role of the arginine-nitric oxide pathway in the pathogenesis of bipolar affective disorder". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 254 (1): 43–47. doi:10.1007/s00406-004-0453-x. PMID 14991378.

- ↑ Fontoura, PC; Pinto, VL; Matsuura, C; Resende Ade, C; de Bem, GF; Ferraz, MR; Cheniaux, E; Brunini, TM; Mendes-Ribeiro, AC (October 2012). "Defective Nitric Oxide–Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate Signaling in Patients With Bipolar Disorder: A Potential Role for Platelet Dysfunction". Psychosomatic Medicine. 74 (8): 873–877. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182689460. PMID 23023680.

- ↑ Bielau, H; Brisch, R; Bernard-Mittelstaedt, J; Dobrowolny, H; Gos, T; Baumann, B; Mawrin, C; Bernstein, HG; Bogerts, B; Steiner, J (June 2012). "Immunohistochemical evidence for impaired nitric oxide signaling of the locus coeruleus in bipolar disorder". Brain Research. 1459: 91–99. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.04.022. PMID 22560594.

- ↑ Gałecki, P; Maes, M; Florkowski, A; Lewiński, A; Gałecka, E; Bieńkiewicz, M; Szemraj, J (March 2011). "Association between inducible and neuronal nitric oxide synthase polymorphisms and recurrent depressive disorder". Journal of Affective Disorders. 129 (1–3): 175–82. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.005. PMID 20888049.

- 1 2 Dhir, A; Kulkarni, SK (April 2011). "Nitric oxide and major depression". Nitric Oxide. 24 (3): 125–131. doi:10.1016/j.niox.2011.02.002. PMID 21335097.

- ↑ Savaş, HA; Herken, H; Yürekli, M; Uz, E; Tutkun, H; Zoroğlu, SS; Ozen, ME; Cengiz, B; Akyol, O (2002). "Possible role of nitric oxide and adrenomedullin in bipolar affective disorder". Neuropsychobiology. 45 (2): 57–61. doi:10.1159/000048677. PMID 11893860.

- ↑ Hallak, Jaime E. C.; Maia-de-Oliveira, J. P.; Abrao, J.; Evora, P. R.; Zuardi, A. W.; Crippa, J. A.; Belmonte-de-Abreu, P.; Baker, G. B.; Dursun, S.M. (8 May 2013). "Rapid improvement of acute schizophrenia symptoms after intravenous sodium nitroprusside: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial" (PDF). The Journal of the American Medical Association. 70 (7): E3–E5. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1292. PMID 23699763. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ↑ A. R. Butler; I. L. Megson (2002). "Non-Heme Iron Nitrosyls in Biology". Chemical Reviews. 102 (4): 1155–1165. doi:10.1021/cr000076d.

- 1 2 3 Catherine E. Housecroft; Alan G. Sharpe (2008). "Chapter 22: d-Block metal chemistry: the first row metals". Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Pearson. p. 721. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- ↑ Jadwiga Tritt-Goc; Narcyz Piślewski; Stanisław K. Hoffmann (1997). "EPR evidence of the paramagnetism of a long-living metastable excited state of a sodium nitroprusside single crystal". Chemical Physics Letters. 268 (5–6): 471–474. Bibcode:1997CPL...268..471T. doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(97)00217-0.

- ↑ Coppens, P.; Novozhilova, I.; Kovalevsky, A. (2002). "Photoinduced Linkage Isomers of Transition-Metal Nitrosyl Compounds and Related Complexes". Chem. Rev. 102 (4): 861–883. doi:10.1021/cr000031c.

- ↑ Hans Reihlen; Adolf v. Friedolsheim (1927). "Über komplexe Stickoxydverbindungen und das sogenannte einwertige Eisen". Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 457: 71–82. doi:10.1002/jlac.19274570103.

- 1 2 J. J. Spijkerman; D. K. Snediker; F. C. Ruegg; J. R. Devoe. NBS Misc. Publ. 260-13: Mossbauer Spectroscopy Standard for the Chemical Shift of Iron Compounds (PDF). National Bureau of Standards. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ↑ O. R. Leeuwenkamp; W. P. van Bennekom; E. J. van der Mark; A. Bult (1984). "Nitroprusside, antihypertensive drug and analytical reagent". Pharmaceutisch Weekblad. 6 (4): 129–140. doi:10.1007/BF01954040.

- ↑ "Sodium Nitrosyl Cyanoferrate" in Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. Edited by G. Brauer, Academic Press, 1963, NY. Vol. 1. p. 1768.

- ↑ Th. Woike; W. Krasser; P. S. Bechthold; S. Haussühl (1984). "Extremely Long-Living Metastable State of Na2[Fe(CN)5NO]·2H2O Single Crystals: Optical". Phys. Rev. Lett. 53: 1767–1770. Bibcode:1984PhRvL..53.1767W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.1767.

- ↑ Barraud, N; Hassett, DJ; Hwang, SH; Rice, SA; Kjelleberg, S; Webb, JS (2006). "Involvement of nitric oxide in biofilm dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa". Journal of Bacteriology. 188 (21): 7344–53. doi:10.1128/JB.00779-06. PMC 1636254. PMID 17050922.

- ↑ Chua SL, Liu Y, Yam JKH, Tolker-Nielsen T, Kjelleberg S, Givskov M, Yang L (2014). "Dispersed cells represent a distinct stage in the transition from bacterial biofilm to planktonic lifestyles". Nature Communications. 5: 4462. doi:10.1038/ncomms5462. PMID 25042103.

- ↑ A. C. H. Rothera (1908). "Note on the sodium nitro-prusside reaction for acetone". J. Physiol. 37 (5–6): 491–494. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1908.sp001285. PMC 1533603. PMID 16992945.

- ↑ Comstock JP; Garber AJ. (1990). "Chapter 140. Ketonuria". In Walker HK; Hall WD; Hurst JW. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations (NCBI Bookshelf) (3rd ed.). Boston: Butterworths. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Finocchiaro R; D'Eufemia P; Celli M; Zaccagnini M; Viozzi L; Troiani P; Mannarino O; Giardini O. (1998). "Usefulness of cyanide-nitroprusside test in detecting incomplete recessive heterozygotes for cystinuria: a standardized dilution procedure". Urol Res. 26 (6): 401–5. doi:10.1007/s002400050076. PMID 9879820.

- ↑ "TLC Visualization Reagents" (PDF). École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ Carol L. O’Neala; Dennis J. Croucha; Alim A. Fatahb (2000). "Validation of twelve chemical spot tests for the detection of drugs of abuse". Forensic Science International. 109 (3): 189–201. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(99)00235-2. PMID 10725655.