Hydrogen sulfide

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic IUPAC name

Hydrogen sulfide[1] | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| 3DMet | B01206 | ||

| 3535004 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.070 | ||

| EC Number | 231-977-3 | ||

| 303 | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Hydrogen+sulfide | ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number | MX1225000 | ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1053 | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| H2S | |||

| Molar mass | 34.08 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless gas | ||

| Odor | Rotten eggs | ||

| Density | 1.363 g dm−3 | ||

| Melting point | −82 °C (−116 °F; 191 K) | ||

| Boiling point | −60 °C (−76 °F; 213 K) | ||

| 4 g dm−3 (at 20 °C) | |||

| Vapor pressure | 1740 kPa (at 21 °C) | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 7.0[2][3] | ||

| Conjugate acid | Sulfonium | ||

| Conjugate base | Bisulfide | ||

| −25.5·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD) |

1.000644 (0 °C)[4] | ||

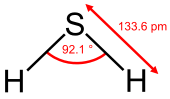

| Structure | |||

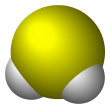

| C2v | |||

| Bent | |||

| 0.97 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C) |

1.003 J K−1 g−1 | ||

Std molar entropy (S |

206 J mol−1 K−1[5] | ||

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH |

−21 kJ mol−1[5] | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Main hazards | Flammable and highly toxic | ||

EU classification (DSD) (outdated) |

|||

| R-phrases (outdated) | R12, R26, R50 | ||

| S-phrases (outdated) | (S1/2), S9, S16, S36, S38, S45, S61 | ||

| NFPA 704 | |||

| Flash point | −82.4 °C (−116.3 °F; 190.8 K) [6] | ||

| 232 °C (450 °F; 505 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 4.3–46% | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LC50 (median concentration) |

| ||

LCLo (lowest published) |

| ||

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

C 20 ppm; 50 ppm [10-minute maximum peak][8] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

C 10 ppm (15 mg/m3) [10-minute][8] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

100 ppm[8] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related hydrogen chalcogenides |

|||

Related compounds |

Phosphine | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

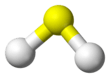

Hydrogen sulfide is the chemical compound with the formula H

2S. It is a colorless chalcogen hydride gas with the characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. It is very poisonous, corrosive, and flammable.[9]

Hydrogen sulfide is often produced from the microbial breakdown of organic matter in the absence of oxygen gas, such as in swamps and sewers; this process is commonly known as anaerobic digestion which is done by sulfate-reducing microorganisms. H

2S also occurs in volcanic gases, natural gas, and in some sources of well water.[10] The human body produces small amounts of H

2S and uses it as a signaling molecule.[11]

Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele is credited with having discovered hydrogen sulfide in 1777.

The British English spelling of this compound is hydrogen sulphide, but this spelling is not recommended by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) or the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Properties

Hydrogen sulfide is slightly denser than air; a mixture of H

2S and air can be explosive. Hydrogen sulfide burns in oxygen with a blue flame to form sulfur dioxide (SO

2) and water. In general, hydrogen sulfide acts as a reducing agent, especially in the presence of base, which forms SH−.

At high temperatures or in the presence of catalysts, sulfur dioxide reacts with hydrogen sulfide to form elemental sulfur and water. This reaction is exploited in the Claus process, an important industrial method to dispose of hydrogen sulfide.

Hydrogen sulfide is slightly soluble in water and acts as a weak acid (pKa = 6.9 in 0.01–0.1 mol/litre solutions at 18 °C), giving the hydrosulfide ion HS−

(also written SH−

). Hydrogen sulfide and its solutions are colorless. When exposed to air, it slowly oxidizes to form elemental sulfur, which is not soluble in water. The sulfide anion S2−

is not formed in aqueous solution.[12]

Hydrogen sulfide reacts with metal ions to form metal sulfides, which are insoluble, often dark colored solids. Lead(II) acetate paper is used to detect hydrogen sulfide because it readily converts to lead(II) sulfide, which is black. Treating metal sulfides with strong acid often liberates hydrogen sulfide.

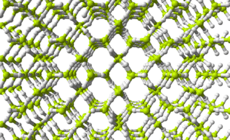

At pressures above 90 GPa (gigapascal), hydrogen sulfide becomes a metallic conductor of electricity. When cooled below a critical temperature this high-pressure phase exhibits superconductivity. The critical temperature increases with pressure, ranging from 23 K at 100 GPa to 150 K at 200 GPa.[13] If hydrogen sulfide is pressurized at higher temperatures, then cooled, the critical temperature reaches 203 K (−70 °C), the highest accepted superconducting critical temperature as of 2015. By substituting a small part of sulfur with phosphorus and using even higher pressures, it has been predicted that it may be possible to raise the critical temperature to above 0 °C (273 K) and achieve room-temperature superconductivity.[14]

Production

Hydrogen sulfide is most commonly obtained by its separation from sour gas, which is natural gas with high content of H

2S. It can also be produced by treating hydrogen with molten elemental sulfur at about 450 °C. Hydrocarbons can serve as a source of hydrogen in this process.[15]

Sulfate-reducing (resp. sulfur-reducing) bacteria generate usable energy under low-oxygen conditions by using sulfates (resp. elemental sulfur) to oxidize organic compounds or hydrogen; this produces hydrogen sulfide as a waste product.

A standard lab preparation is to treat ferrous sulfide with a strong acid in a Kipp generator:

- FeS + 2 HCl → FeCl2 + H2S

For use in qualitative inorganic analysis, thioacetamide is used to generate H

2S:

- CH3C(S)NH2 + H2O → CH3C(O)NH2 + H2S

Many metal and nonmetal sulfides, e.g. aluminium sulfide, phosphorus pentasulfide, silicon disulfide liberate hydrogen sulfide upon exposure to water:[16]

- 6 H2O + Al2S3 → 3 H2S + 2 Al(OH)3

This gas is also produced by heating sulfur with solid organic compounds and by reducing sulfurated organic compounds with hydrogen.

Water heaters can aid the conversion of sulfate in water to hydrogen sulfide gas. This is due to providing a warm environment sustainable for sulfur bacteria and maintaining the reaction which interacts between sulfate in the water and the water heater anode, which is usually made from magnesium metal.[17]

Biosynthesis in the body

Hydrogen sulfide can be generated in cells via enzymatic or non enzymatic pathway. Hydrogen sulfide made by the non-enzymatic pathway is derived from proteins such as ferredoxins and Rieske proteins. Most hydrogen sulfide is produced from the enzymatic pathway. The endogenous hydrogen sulfide is produced by the enzymes cystathionine beta synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE). L-Cysteine is the main substrate for hydrogen sulfide synthesis.[18]

Uses

Production of sulfur, thioorganic compounds, and alkali metal sulfides

The main use of hydrogen sulfide is as a precursor to elemental sulfur. Several organosulfur compounds are produced using hydrogen sulfide. These include methanethiol, ethanethiol, and thioglycolic acid.[15]

Upon combining with alkali metal bases, hydrogen sulfide converts to alkali hydrosulfides such as sodium hydrosulfide and sodium sulfide:

- H2S + NaOH → NaSH + H2O

- NaSH + NaOH → Na2S + H2O

These compounds are used in the paper making. Specifically, salts of SH− break bonds between lignin and cellulose components of pulp in the Kraft process.[15]

Analytical chemistry

For well over a century, hydrogen sulfide was important in analytical chemistry, in the qualitative inorganic analysis of metal ions. In these analyses, heavy metal (and nonmetal) ions (e.g., Pb(II), Cu(II), Hg(II), As(III)) are precipitated from solution upon exposure to H

2S. The components of the resulting precipitate redissolve with some selectivity, and are thus identified.

Precursor to metal sulfides

As indicated above, many metal ions react with hydrogen sulfide to give the corresponding metal sulfides. This conversion is widely exploited. For example, gases or waters contaminated by hydrogen sulfide can be cleaned with metals, by forming metal sulfides. In the purification of metal ores by flotation, mineral powders are often treated with hydrogen sulfide to enhance the separation. Metal parts are sometimes passivated with hydrogen sulfide. Catalysts used in hydrodesulfurization are routinely activated with hydrogen sulfide, and the behavior of metallic catalysts used in other parts of a refinery is also modified using hydrogen sulfide.

Miscellaneous applications

Hydrogen sulfide is used to separate deuterium oxide, or heavy water, from normal water via the Girdler sulfide process.

Scientists from the University of Exeter discovered that cell exposure to small amounts of hydrogen sulfide gas can prevent mitochondrial damage. When the cell is stressed with disease, enzymes are drawn into the cell to produce small amounts of hydrogen sulfide. This study could have further implications on preventing strokes, heart disease and arthritis.[19]

Occurrence

Small amounts of hydrogen sulfide occur in crude petroleum, but natural gas can contain up to 90%. Volcanoes and some hot springs (as well as cold springs) emit some H

2S, where it probably arises via the hydrolysis of sulfide minerals, i.e. MS + H

2O → MO + H

2S. Hydrogen sulfide can be present naturally in well water, often as a result of the action of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Hydrogen sulfide is created by the human body in small doses through bacterial breakdown of proteins containing sulfur in the intestinal tract. It is also produced in the mouth (halitosis).[20]

A portion of global H

2S emissions are due to human activity. By far the largest industrial source of H

2S is petroleum refineries: The hydrodesulfurization process liberates sulfur from petroleum by the action of hydrogen. The resulting H

2S is converted to elemental sulfur by partial combustion via the Claus process, which is a major source of elemental sulfur. Other anthropogenic sources of hydrogen sulfide include coke ovens, paper mills (using the Kraft process), tanneries and sewerage. H

2S arises from virtually anywhere where elemental sulfur comes in contact with organic material, especially at high temperatures. Depending on environmental conditions, it is responsible for deterioration of material through the action of some sulfur oxidizing microorganisms. It is called biogenic sulfide corrosion.

In 2011 it was reported that increased concentration of H

2S, possibly due to oil field practices, was observed in the Bakken formation crude and presented challenges such as "health and environmental risks, corrosion of wellbore, added expense with regard to materials handling and pipeline equipment, and additional refinement requirements".[21]

Besides living near a gas and oil drilling operations, ordinary citizens can be exposed to hydrogen sulfide by being near waste water treatment facilities, landfills and farms with manure storage. Exposure occurs through breathing contaminated air or drinking contaminated water.[22]

Removal from water

A number of processes designed to remove hydrogen sulfide from drinking water.[23]

- Continuous chlorination

- For levels up to 75 mg/L chlorine is used in the purification process as an oxidizing chemical to react with hydrogen sulfide. This reaction yields insoluble solid sulfur. Usually the chlorine used is in the form of sodium hypochlorite.[24]

- Aeration

- For concentrations of hydrogen sulfide less than 2 mg/L aeration is an ideal treatment process. Oxygen is added to water and a reaction between oxygen and hydrogen sulfide react to produce odorless sulfate[25]

- Nitrate addition

- Calcium nitrate can be used to prevent hydrogen sulfide formation in wastewater streams.

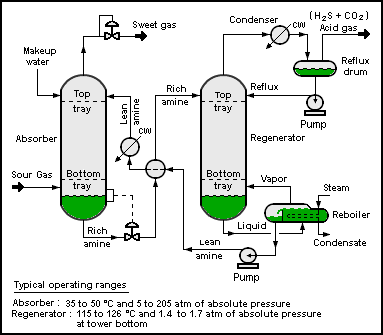

Removal from fuel gases

Hydrogen sulfide is commonly found in raw natural gas and biogas. It is typically removed by amine gas treating technologies. In such processes, the hydrogen sulfide is first converted to an ammonium salt, whereas the natural gas is unaffected.

- RNH2 + H2S ⇌ RNH+

3 + SH−

The bisulfide anion is subsequently regenerated by heating of the amine sulfide solution. Hydrogen sulfide generated in this process is typically converted to elemental sulfur using the Claus Process.

Safety

Hydrogen sulfide is a highly toxic and flammable gas (flammable range: 4.3–46%). Being heavier than air, it tends to accumulate at the bottom of poorly ventilated spaces. Although very pungent at first, it quickly deadens the sense of smell, so victims may be unaware of its presence until it is too late. For safe handling procedures, a hydrogen sulfide safety data sheet (SDS) should be consulted.[26]

Toxicity

Hydrogen sulfide is a broad-spectrum poison, meaning that it can poison several different systems in the body, although the nervous system is most affected. The toxicity of H

2S is comparable with that of carbon monoxide.[27] It binds with iron in the mitochondrial cytochrome enzymes, thus preventing cellular respiration.

Since hydrogen sulfide occurs naturally in the body, the environment, and the gut, enzymes exist to detoxify it. At some threshold level, believed to average around 300–350 ppm, the oxidative enzymes become overwhelmed. Many personal safety gas detectors, such as those used by utility, sewage and petrochemical workers, are set to alarm at as low as 5 to 10 ppm and to go into high alarm at 15 ppm. Detoxification is effected by oxidation to sulfate, which is harmless.[28] Hence, low levels of hydrogen sulfide may be tolerated indefinitely.

Diagnostic of extreme poisoning by H

2S is the discolouration of copper coins in the pockets of the victim. Treatment involves immediate inhalation of amyl nitrite, injections of sodium nitrite, or administration of 4-dimethylaminophenol in combination with inhalation of pure oxygen, administration of bronchodilators to overcome eventual bronchospasm, and in some cases hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT).[27] HBOT has clinical and anecdotal support.[29][30][31]

Exposure to lower concentrations can result in eye irritation, a sore throat and cough, nausea, shortness of breath, and fluid in the lungs (pulmonary edema).[27] These effects are believed to be due to the fact that hydrogen sulfide combines with alkali present in moist surface tissues to form sodium sulfide, a caustic.[32] These symptoms usually go away in a few weeks.

Long-term, low-level exposure may result in fatigue, loss of appetite, headaches, irritability, poor memory, and dizziness. Chronic exposure to low level H

2S (around 2 ppm) has been implicated in increased miscarriage and reproductive health issues among Russian and Finnish wood pulp workers,[33] but the reports have not (as of circa 1995) been replicated.

Short-term, high-level exposure can induce immediate collapse, with loss of breathing and a high probability of death. If death does not occur, high exposure to hydrogen sulfide can lead to cortical pseudolaminar necrosis, degeneration of the basal ganglia and cerebral edema.[27] Although respiratory paralysis may be immediate, it can also be delayed up to 72 hours.[34]

- 0.00047 ppm or 0.47 ppb is the odor threshold, the point at which 50% of a human panel can detect the presence of an odor without being able to identify it.[35]

- 10 ppm is the OSHA permissible exposure limit (PEL) (8 hour time-weighted average).[20]

- 10–20 ppm is the borderline concentration for eye irritation.

- 20 ppm is the acceptable ceiling concentration established by OSHA.[20]

- 50 ppm is the acceptable maximum peak above the ceiling concentration for an 8-hour shift, with a maximum duration of 10 minutes.[20]

- 50–100 ppm leads to eye damage.

- At 100–150 ppm the olfactory nerve is paralyzed after a few inhalations, and the sense of smell disappears, often together with awareness of danger.[36][37]

- 320–530 ppm leads to pulmonary edema with the possibility of death.[27]

- 530–1000 ppm causes strong stimulation of the central nervous system and rapid breathing, leading to loss of breathing.

- 800 ppm is the lethal concentration for 50% of humans for 5 minutes' exposure (LC50).

- Concentrations over 1000 ppm cause immediate collapse with loss of breathing, even after inhalation of a single breath.

Incidents

Hydrogen sulfide was used by the British Army as a chemical weapon during World War I. It was not considered to be an ideal war gas, but, while other gases were in short supply, it was used on two occasions in 1916.[38]

In 1975, a hydrogen sulfide release from an oil drilling operation in Denver City, Texas, killed nine people and caused the state legislature to focus on the deadly hazards of the gas. State Representative E L Short took the lead in endorsing an investigation by the Texas Railroad Commission and urged that residents be warned "by knocking on doors if necessary" of the imminent danger stemming from the gas. One may die from the second inhalation of the gas, and a warning itself may be too late.[39]

On September 2, 2005, a leak in the propeller room of a Royal Caribbean Cruise Liner docked in Los Angeles resulted in the deaths of 3 crewmen due to a sewage line leak. As a result, all such compartments are now required to have a ventilation system.[40][41]

A dump of toxic waste containing hydrogen sulfide is believed to have caused 17 deaths and thousands of illnesses in Abidjan, on the West African coast, in the 2006 Côte d'Ivoire toxic waste dump.

In 2014, levels of hydrogen sulfide as high as 83 ppm have been detected at a recently built mall in Thailand called Siam Square One at the Siam Square area. Shop tenants at the mall reported health complications such as sinus inflammation, breathing difficulties and eye irritation. After investigation it was determined that the large amount of gas originated from imperfect treatment and disposal of waste water in the building.[42]

In November 2014, a substantial amount of hydrogen sulfide gas shrouded the central, eastern and southeastern parts of Moscow. Residents living in the area were urged to stay indoors by the emergencies ministry. Although the exact source of the gas was not known, blame had been placed on a Moscow oil refinery.[43]

In June 2016, a mother and her daughter were found deceased in their still-running Porsche Cayenne SUV against a guardrail on Florida's Turnpike, initially thought to be victims of carbon monoxide poisoning.[44][45] Their deaths remained unexplained as the medical examiner waited for results of toxicology tests on the victims,[46] until urine tests revealed that hydrogen sulfide was the cause of death.[47] A report from the Orange-Osceola Medical Examiner’s Office indicated that toxic fumes came from the Porsche’s battery, located under the front passenger seat.[48][49]

In January 2017, three utility workers in Key Largo, Florida, died one by one within seconds of descending into a narrow space beneath a manhole cover to check a section of paved street,[50] the hole was filled with hydrogen sulfide and methane gas created from years of rotted vegetation.[51] In an attempt to save the men, a firefighter who entered the hole without his air tank (because he could not fit through the hole with it) collapsed within seconds and had to be rescued by a colleague.[52][53] The firefighter was airlifted to Jackson Memorial Hospital and later recovered.[54][55]

Suicides

The gas, produced by mixing certain household ingredients, was used in a suicide wave in 2008 in Japan.[56] The wave prompted staff at Tokyo's suicide prevention center to set up a special hot line during "Golden Week", as they received an increase in calls from people wanting to kill themselves during the annual May holiday.[57]

As of 2010, this phenomenon has occurred in a number of US cities, prompting warnings to those arriving at the site of the suicide.[58][59][60][61][62] These first responders, such as emergency services workers or family members are at risk of death from inhaling lethal quantities of the gas, or by fire.[63][64] Local governments have also initiated campaigns to prevent such suicides.

Hydrogen sulfide in the natural environment

Microbial: The sulfur cycle

Hydrogen sulfide is a central participant in the sulfur cycle, the biogeochemical cycle of sulfur on Earth.[65]

In the absence of oxygen, sulfur-reducing and sulfate-reducing bacteria derive energy from oxidizing hydrogen or organic molecules by reducing elemental sulfur or sulfate to hydrogen sulfide. Other bacteria liberate hydrogen sulfide from sulfur-containing amino acids; this gives rise to the odor of rotten eggs and contributes to the odor of flatulence.

As organic matter decays under low-oxygen (or hypoxic) conditions (such as in swamps, eutrophic lakes or dead zones of oceans), sulfate-reducing bacteria will use the sulfates present in the water to oxidize the organic matter, producing hydrogen sulfide as waste. Some of the hydrogen sulfide will react with metal ions in the water to produce metal sulfides, which are not water-soluble. These metal sulfides, such as ferrous sulfide FeS, are often black or brown, leading to the dark color of sludge.

Several groups of bacteria can use hydrogen sulfide as fuel, oxidizing it to elemental sulfur or to sulfate by using dissolved oxygen, metal oxides (e.g., Fe oxyhydroxides and Mn oxides), or nitrate as electron acceptors.[66]

The purple sulfur bacteria and the green sulfur bacteria use hydrogen sulfide as an electron donor in photosynthesis, thereby producing elemental sulfur. (In fact, this mode of photosynthesis is older than the mode of cyanobacteria, algae, and plants, which uses water as electron donor and liberates oxygen.)

The biochemistry of hydrogen sulfide is a key part of the chemistry of the iron-sulfur world. In this model of the origin of life on Earth, geologically produced hydrogen sulfide is postulated as an electron donor driving the reduction of carbon dioxide.[67]

Animals

Hydrogen sulfide is lethal to most animals, but a few highly specialized species (extremophiles) do thrive in habitats that are rich in this compound.[68]

In the deep sea, hydrothermal vents and cold seeps with high levels of hydrogen sulfide are home to a number of extremely specialized lifeforms, ranging from bacteria to fish.[69] Because of the absence of light at these depths, these ecosystems rely on chemosynthesis rather than photosynthesis.[70]

Freshwater springs rich in hydrogen sulfide are mainly home to invertebrates, but also include a small number of fish: Cyprinodon bobmilleri (a pupfish from Mexico), Limia sulphurophila (a poeciliid from the Dominican Republic), Gambusia eurystoma (a poeciliid from Mexico), and a few Poecilia (poeciliids from Mexico).[68][71] Invertebrates and microorganisms in some cave systems, such as Movile Cave, are adapted to high levels of hydrogen sulfide.[72]

Interstellar and planetary occurrence

Hydrogen sulfide has often been detected in the interstellar medium.[73] It also occurs in the clouds of planets in our solar system.[74]

Mass extinctions

Hydrogen sulfide has been implicated in several mass extinctions that have occurred in the Earth's past. In particular, a buildup of hydrogen sulfide in the atmosphere may have caused the Permian-Triassic extinction event 252 million years ago.[75]

Organic residues from these extinction boundaries indicate that the oceans were anoxic (oxygen-depleted) and had species of shallow plankton that metabolized H

2S. The formation of H

2S may have been initiated by massive volcanic eruptions, which emitted carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, which warmed the oceans, lowering their capacity to absorb oxygen that would otherwise oxidize H

2S. The increased levels of hydrogen sulfide could have killed oxygen-generating plants as well as depleted the ozone layer, causing further stress. Small H

2S blooms have been detected in modern times in the Dead Sea and in the Atlantic ocean off the coast of Namibia.[75]

See also

References

- ↑ "Hydrogen Sulfide - PubChem Public Chemical Database". The PubChem Project. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- ↑ Perrin, D.D. (1982). Ionisation Constants of Inorganic Acids and Bases in Aqueous Solution (2nd ed.). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- ↑ Bruckenstein, S.; Kolthoff, I.M., in Kolthoff, I.M.; Elving, P.J. Treatise on Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 1, pt. 1; Wiley, NY, 1959, pp. 432–433.

- ↑ Patnaik, Pradyot (2002). Handbook of Inorganic Chemicals. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-049439-8.

- 1 2 Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles (6th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A23. ISBN 0-618-94690-X.

- ↑ "Hydrogen sulfide". npi.gov.au.

- 1 2 "Hydrogen sulfide". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- 1 2 3 "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0337". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-08-037941-9.

- ↑ "Hydrogen Sulphide In Well Water". Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ↑ Bos, E. M; Van Goor, H; Joles, J. A; Whiteman, M; Leuvenink, H. G (2015). "Hydrogen sulfide: Physiological properties and therapeutic potential in ischaemia". British Journal of Pharmacology. 172 (6): 1479–1493. doi:10.1111/bph.12869. PMC 4369258.

- ↑ May, P.M.; Batka, D.; Hefter, G.; Könignberger, E.; Rowland, D. (2018). "Goodbye to S2-". Chem. Comm. 54 (16): 1980. doi:10.1039/c8cc00187a. PMID 29404555.

- ↑ Drozdov, A.; Eremets, M. I.; Troyan, I. A. (2014). "Conventional superconductivity at 190 K at high pressures". arXiv:1412.0460 [cond-mat.supr-con].

- ↑ Cartlidge, Edwin (18 August 2015). "Superconductivity record sparks wave of follow-up physics". Nature News. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 Francois Pouliquen; Claude Blanc; Emmanuel Arretz; Ives Labat; Jacques Tournier-Lasserve; Alain Ladousse; Jean Nougayrede; Gérard Savin; Raoul Ivaldi; Monique Nicolas; Jean Fialaire; René Millischer; Charles Azema; Lucien Espagno; Henri Hemmer; Jacques Perrot (200). "Hydrogen Sulfide". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Chemical Industry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_467.

- ↑ McPherson, William (1913). Laboratory manual. Boston: Ginn and Company. p. 445.

- ↑ "Why Does My Water Smell Like Rotten Eggs? Hydrogen Sulfide and Sulfur Bacteria in Well Water". Minnesota Department of Health. Minnesota Department of Health. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ Rose, Peter; Moore, Philip K.; Zhu, Yi Zhun (2017). "H2S biosynthesis and catabolism: new insights from molecular studies". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 74 (8): 1391–1412. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2406-8. ISSN 1420-682X. PMC 5357297. PMID 27844098.

- ↑ Stampler, Laura. "A Stinky Compound May Protect Against Cell Damage, Study Finds". Time. Time. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (July 2006). "Toxicological Profile For Hydrogen Sulfide" (PDF). p. 154. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ↑ OnePetro. "Home - OnePetro". onepetro.org.

- ↑ "Hydrogen Sulfide" (PDF). Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. December 2016.

- ↑ Lemley, Ann T.; Schwartz, John J.; Wagenet, Linda P. "Hydrogen Sulfide in Household Drinking Water" (PDF). Cornell University.

- ↑ "Hydrogen Sulfide (Rotten Egg Odor) in Pennsylvania Groundwater Wells". Penn State. Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ McFarland, Mark L.; Provin, T. L. "Hydrogen Sulfide in Drinking Water Treatment Causes and Alternatives" (PDF). Texas A&M University. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ Iowa State University, Department of Chemistry MSDS. "Hydrogen Sulfide Material Safety Data Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lindenmann, J.; Matzi, V.; Neuboeck, N.; Ratzenhofer-Komenda, B.; Maier, A; Smolle-Juettner, F. M. (December 2010). "Severe hydrogen sulphide poisoning treated with 4-dimethylaminophenol and hyperbaric oxygen". Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. 40 (4): 213–217. PMID 23111938. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ↑ Ramasamy, S.; Singh, S.; Taniere, P.; Langman, M. J. S.; Eggo, M. C. (2006). "Sulfide-detoxifying enzymes in the human colon are decreased in cancer and upregulated in differentiation". Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 291 (2): G288–96. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00324.2005. PMID 16500920. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

- ↑ Gerasimon, G.; Bennett, S.; Musser, J.; Rinard, J. (May 2007). "Acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning in a dairy farmer". Clin. Toxicol. 45 (4): 420–423. doi:10.1080/15563650601118010. PMID 17486486. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ↑ Belley, R.; Bernard, N.; Côté, M; Paquet, F.; Poitras, J. (July 2005). "Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the management of two cases of hydrogen sulfide toxicity from liquid manure". CJEM. 7 (4): 257–261. doi:10.1017/s1481803500014408. PMID 17355683. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ↑ Hsu, P.; Li, H.-W.; Lin, Y.-T. (1987). "Acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning treated with hyperbaric oxygen". J. Hyperbaric Med. 2 (4): 215–221. ISSN 0884-1225. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ↑ Lewis, R.J. (1996). Sax's Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials. 1–3 (9th ed.). New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- ↑ Hemminki, K.; Niemi, M. L. (1982). "Community study of spontaneous abortions: relation to occupation and air pollution by sulfur dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and carbon disulfide". Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 51 (1): 55–63. doi:10.1007/bf00378410. PMID 7152702.

- ↑ "The chemical suicide phenomenon". Firerescue1.com. 2011-02-07. Retrieved 2013-12-19.

- ↑ Iowa State University Extension (May 2004). "The Science of Smell Part 1: Odor perception and physiological response" (PDF). PM 1963a. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ↑ USEPA; Health and Environmental Effects Profile for Hydrogen Sulfide p.118-8 (1980) ECAO-CIN-026A

- ↑ Zenz, C.; Dickerson, O.B.; Horvath, E.P. (1994). Occupational Medicine (3rd ed.). St. Louis, MO. p. 886.

- ↑ Foulkes, Charles Howard (2001) [First published Blackwood & Sons, 1934]. "Gas!" The story of the special brigade. Published by Naval & Military P. p. 105. ISBN 1-84342-088-0.

- ↑ Howard Swindle, "The Deadly Smell of Success". Texas Monthly, June 1975. June 1975. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ↑ County of Los Angeles: Department of Public Health (PDF) http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/acd/reports/spclrpts/spcrpt05/DeathsHydrogenSulfide05.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Gas Kills 3 Crewmen on Ship". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Do not breathe: Dangerous, toxic gas found at Siam Square One". Coconuts Bangkok. Coconuts Media. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "Russian capital Moscow shrouded in noxious gas". BBC News Europe. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sources: Mom, daughter found dead in Porsche likely died from carbon monoxide". WFTV. 7 June 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

Both had red skin and rash-like symptoms, and had vomited, sources said.

- ↑ Salinger, Tobias (4 October 2016). "Woman, girl died after inhaling hydrogen sulfide, coroners say". New York Daily News. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ Lotan, Gal Tziperman (4 October 2016). "Hydrogen sulfide inhalation killed mother, toddler found on Florida's Turnpike in June". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ Zilber, Ariel. "Florida woman and her daughter who died in Porsche inhaled toxic gas". dailymail.co.uk. Mail Online. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ Kealing, Bob. "Medical examiner confirms suspected cause of deaths in Turnpike mystery". Archived from the original on 2016-10-05. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- ↑ Bell, Lisa (19 March 2017). "Hidden car dangers you should be aware of". ClickOrlando.com. Produced by Donovan Myrie. WKMG-TV. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

Porsche Cayennes, along with a few other vehicles, have their batteries in the passenger compartment.

- ↑ "One by one, 3 utility workers descended into a manhole. One by one, they died". www.washingtonpost.com.

- ↑ Rabin, Charles; Goodhue, David (16 January 2017). "Three Keys utility workers die in wastewater trench". Miami Herald. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ Herrin, Becky (16 January 2017). "Detectives investigating deaths of three men". floridakeyssheriff.blogspot.com. Monroe County Sheriff's Office. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ Goodhue, David (17 January 2017). "Firefighter who tried to save 3 men in a manhole is fighting for his life". Miami Herald. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "Key Largo firefighter takes first steps since nearly getting killed". WSVN. 18 January 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "Firefighter who survived Key Largo rescue attempt that killed 3 leaves hospital". Sun-Sentinel. Associated Press. 26 January 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "Dangerous Japanese 'Detergent Suicide' Technique Creeps Into U.S". Wired.com. Wired. March 13, 2009.

- ↑ Namiki, Noriko (2008-05-22). "Terrible Twist in Japan Suicide Spates - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved 2013-12-19.

- ↑ http://info.publicintelligence.net/LARTTAChydrogensulfide.pdf

- ↑ http://info.publicintelligence.net/MAchemicalsuicide.pdf

- ↑ http://info.publicintelligence.net/illinoisH2Ssuicide.pdf

- ↑ http://info.publicintelligence.net/NYhydrogensulfide.pdf

- ↑ http://info.publicintelligence.net/KCTEWhydrogensulfide.pdf

- ↑ dhmh.maryland.gov Archived January 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Scoville, Dean (April 2011). "Chemical Suicides - Article - POLICE Magazine". Policemag.com. Retrieved 2013-12-19.

- ↑ Barton, Larry L.; Fardeau, Marie-Laure; Fauque, Guy D. (2014). "Chapter 10. Hydrogen Sulfide: A Toxic Gas Produced by Dissimilatory Sulfate and Sulfur Reduction and Consumed by Microbial Oxidation". In Kroneck, Peter M.H.; Sosa Torres, Martha E. The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 14. Springer. pp. 237–277. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_10.

- ↑ Jørgensen, B. B.; Nelson, D. C. (2004). "Sulfide oxidation in marine sediments: Geochemistry meets microbiology". In Amend, J. P.; Edwards, K. J.; Lyons, T. W. Sulfur Biogeochemistry – Past and Present. Geological Society of America. pp. 36–81.

- ↑ "The very first surface organism can be characterized as a catalyst for accelerating the formation of pyrite by providing a catalytic pathway for the flow of electrons from hydrogen sulfide to carbon dioxide." Wächtershäuser, Günter (1988-12-01). "Before enzymes and templates: theory of surface metabolism". Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 52 (4): 452–84. PMC 373159. PMID 3070320. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- 1 2 Tobler, M; Riesch, R.; García de León, F. J.; Schlupp, I.; Plath, M. (2008). "Two endemic and endangered fishes, Poecilia sulphuraria (Álvarez, 1948) and Gambusia eurystoma Miller, 1975 (Poeciliidae, Teleostei) as only survivors in a small sulphidic habitat". Journal of Fish Biology. 72 (3): 523–533. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01716.x.

- ↑ Bernardino, Angelo F.; Levin, Lisa A.; Thurber, Andrew R.; Smith, Craig R. (2012). "Comparative Composition, Diversity and Trophic Ecology of Sediment Macrofauna at Vents, Seeps and Organic Falls". PLoS ONE. 7 (4): e33515. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...733515B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033515. PMC 3319539. PMID 22496753.

- ↑ "Hydrothermal Vents". Marine Society of Australia. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ Palacios, Maura; Arias-Rodríguez, Lenín; Plath, Martin; Eifert, Constanze; Lerp, Hannes; Lamboj, Anton; Voelker, Gary; Tobler, Michael (2013). "The Rediscovery of a Long Described Species Reveals Additional Complexity in Speciation Patterns of Poeciliid Fishes in Sulfide Springs". PLoS ONE. 8 (8): e71069. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...871069P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071069. PMC 3745397. PMID 23976979.

- ↑ Kumaresan, Deepak; Wischer, Daniela; Stephenson, Jason; Hillebrand-Voiculescu, Alexandra; Murrell, J. Colin (2014). "Microbiology of Movile Cave—A Chemolithoautotrophic Ecosystem". Geomicrobiology Journal. 31 (3): 186–193. doi:10.1080/01490451.2013.839764. ISSN 0149-0451.

- ↑ Despois, D. (1999). "Radio line observations of molecular and isotopic species in comet C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp) Implications on the interstellar origin of cometary ices". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 79: 103–124.

- ↑ Irwin, P. G. J.; Toledo, D.; Garland, R.; Teanby, N. A.; Fletcher, L. N.; Orton, G. A.; Bézard, B. (2018). "Detection of hydrogen sulfide above the clouds in Uranus's atmosphere". Nature Astronomy. 2 (5): 420–427. Bibcode:2018NatAs...2..420I. doi:10.1038/s41550-018-0432-1.

- 1 2 "Impact from the Deep". Scientific American. October 2006.

Additional resources

- Committee on Medical and Biological Effects of Environmental Pollutants (1979). Hydrogen Sulfide. Baltimore: University Park Press. ISBN 0-8391-0127-9.

- Siefers, Andrea (2010). A novel and cost-effective hydrogen sulfide removal technology using tire derived rubber particles (MS thesis). Iowa State University. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hydrogen sulfide. |

- International Chemical Safety Card 0165

- Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 53

- National Pollutant Inventory - Hydrogen sulfide fact sheet

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- NACE (National Association of Corrosion Epal)