Nitroso

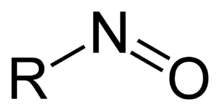

Nitroso refers to a functional group in organic chemistry which has the NO group attached to an organic moiety. As such, various nitroso groups can be categorized as C-nitroso compounds (e.g., nitrosoalkanes; R−N=O), S-nitroso compounds (nitrosothiols; RS−N=O), N-nitroso compounds (e.g., nitrosamines, R1N(−R2)−N=O), and O-nitroso compounds (alkyl nitrites; RO−N=O).

Organonitroso compounds

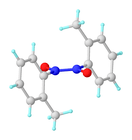

Nitrosobenzene ((C6H5NO) is prepared by reduction of nitrobenzene to phenylhydroxylamine (C6H5NHOH), which is then oxidized.[1] Nitrosoarenes typically participate in a monomer-dimer equilibrium. The dimers, which are often pale-yellow, are often favored in the solid state, whereas the deeply colored monomers are favored in dilution solution or at higher temperatures. They exist as cis- and trans-isomers.[2]

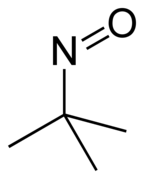

Nitroso compounds can be prepared by the reduction of nitro compounds or by the oxidation of hydroxylamines. A good example is (CH3)3CNO, known formally as 2-methyl-2-nitrosopropane, or t-BuNO.[4] (CH3)3CNO is blue and exists in solution in equilibrium with its dimer, which is colorless, m.p. 80–81 °C.

In the Fischer–Hepp rearrangement aromatic 4-nitrosoanilines are prepared from the corresponding nitrosamines. Another named reaction involving a nitroso compound is the Barton reaction.

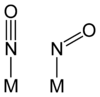

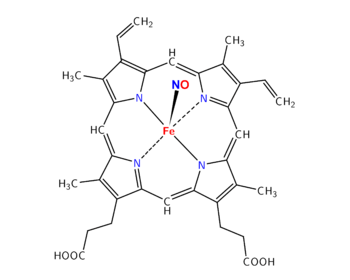

Organonitroso compounds serve as a ligands for transition metals.[5]

Due to the stability of the nitric oxide free radical, nitroso organyls tend to have very low C–N bond dissociation energies: nitrosoalkanes have BDEs on the order of 30 to 40 kcal/mol, while nitrosoarenes have BDEs on the order of 50 to 60 kcal/mol. As a consequence, they are generally heat- and light-sensitive. Compounds containing O–(NO) or N–(NO) bonds generally have even lower bond dissociation energies. For instance, N-nitrosodiphenylamine, Ph2N–N=O, has a N–N bond dissociation energy of only 23 kcal/mol.[6]

Nitrosation vs. nitrosylation

Nitrite can enter two kinds of reaction, depending on the physico-chemical environment.

- Nitrosylation is adding a nitrosyl ion NO− to a metal (e.g. iron) or a thiol, leading to nitrosyl iron Fe–NO (e.g., in nitrosylated heme = nitrosylheme) or S-nitrosothiols (RSNOs).

- Nitrosation is adding a nitrosonium ion NO+ to an amine –NH2 leading to a nitrosamine. This conversion occurs at acidic pH, particularly in the stomach, as shown in the equation for the formation of N-phenylnitrosamine:

- NO−

2 + H+ ⇌ HONO - HONO + H+ ⇌ H2O + NO+

- C6H5NH2 + NO+ → C6H5N(H)NO + H+

- NO−

Many primary alkyl N-nitroso compounds, such as CH3N(H)NO, tend to be unstable with respect to hydrolysis to the alcohol. Those derived from secondary amines (e.g., (CH3)2NNO derived from dimethylamine) are more robust. It is these N-nitrosamines that are carcinogens in rodents.

Nitrosyl in inorganic chemistry

Nitrosyls are non-organic compounds containing the NO group, for example directly bound to the metal via the N atom, giving a metal–NO moiety. Alternatively, a nonmetal example is the common reagent nitrosyl chloride (Cl−N=O). Nitric oxide is a stable radical, having an unpaired electron. Reduction of nitric oxide gives the hyponitrite anion, NO−:

- NO + e− → NO−

Oxidation of NO yields the nitrosonium cation, NO+:

- NO → NO+ + e−

Nitric oxide can serve as a ligand forming metal nitrosyl complexes or just metal nitrosyls. These complexes can be viewed as adducts of NO+, NO−, or some intermediate case.

In food

In foodstuffs and in the gastro-intestinal tract, nitrosation and nitrosylation do not have the same consequences on consumer health.

- In cured meat: Meat processed by curing contains nitrite and has a pH of 5 approximately, where almost all nitrite is present as NO−

2 (99%). Cured meat is also added with sodium ascorbate (or erythorbate or vitamin C). As demonstrated by S. Mirvish, ascorbate inhibits nitrosation of amines to nitrosamine, because ascorbate reacts with NO−

2 to form NO.[7][8] Ascorbate and pH 5 thus favor nitrosylation of heme iron, forming nitrosylheme, a red pigment when included inside myoglobin, and a pink pigment when it has been released by cooking. It participates to the "bacon flavor" of cured meat: nitrosylheme is thus considered a benefit for the meat industry and for consumers.[9] - In the stomach: secreted hydrogen chloride makes an acidic environment (pH=2) and ingested nitrite (with food or saliva) leads to nitrosation of amines, that yields nitrosamines (potential carcinogens). Nitrosation is low if amine concentration is low (e.g., low-protein diet, no fermented food) or if vitamin C concentration is high (e.g., high fruit diet). Then S-nitrosothiols are formed, that are stable at pH 2.

- In the colon: neutral pH does not favor nitrosation. No nitrosamine is formed in stools, even after addition of a secondary amine or nitrite.[10] Neutral pH favors NO− release from S-nitrosothiols, and nitrosylation of iron. The previously called NOC (N-nitroso compounds) measured by Bingham's team in stools from red meat-fed volunteers[11] were, according to Bingham and Kuhnle, largely non-N-nitroso ATNC (apparent total nitroso compounds), e.g., S-nitrosothiols and nitrosyl iron (as nitrosyl heme).[12]

See also

- Nitrosamine, the functional group with the NO attached to an amine, such as R2N–NO

- Nitrosobenzene

- Nitric oxide

- Nitroxyl

References

- ↑ G. H. Coleman, C. M. McCloskey, F. A. Stuart (1945). "Nitrosobenzene". Org. Synth. 25: 80. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.025.0080.

- ↑ Beaudoin, D.; Wuest, J. D. (2016). "Dimerization of Aromatic C-Nitroso Compounds". Chemical Reviews. 116: 258–286. doi:10.1021/cr500520s.

- ↑ E.Bosch (2014). "Structural Analysis of Methyl-Substituted Nitrosobenzenes and Nitrosoanisoles". J. Chem. Cryst. 98: 44. doi:10.1007/s10870-013-0489-8.

- ↑ Calder, A.; Forrester, A. R.; Hepburn, S. P. "2-Methyl-2-nitrosopropane and Its Dimer". Organic Syntheses. 52: 77. ; Collective Volume, 6, , p. 803

- ↑ Pilato, R. S.; McGettigan, C.; Geoffroy, G. L.; Rheingold, A. L.; Geib, S. J. (1990). "tert-Butylnitroso complexes. Structural characterization of W(CO)5(N(O)Bu-tert) and [CpFe(CO)(PPh3)(N(O)Bu-tert)]+". Organometallics. 9: 312–17. doi:10.1021/om00116a004.

- ↑ Luo, Yu-Ran (2007). Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies. Boca Raton, Fl.: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9781420007282.

- ↑ Mirvish, SS; Wallcave, L; Eagen, M; Shubik, P (July 1972). "Ascorbate–nitrite reaction: possible means of blocking the formation of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds". Science. 177 (4043): 65–8. Bibcode:1972Sci...177...65M. doi:10.1126/science.177.4043.65. PMID 5041776.

- ↑ Mirvish, SS (October 1986). "Effects of vitamins C and E on N-nitroso compound formation, carcinogenesis, and cancer". Cancer. 58 (8 Suppl): 1842–50. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19861015)58:8+<1842::aid-cncr2820581410>3.0.co;2-#. PMID 3756808.

- ↑ Honikel, K. O. (2008). "The use an control of nitrate and nitrite for the processing of meat products". Meat Science. 78: 68–76. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.05.030. PMID 22062097.

- ↑ Lee, L; Archer, MC; Bruce, WR (October 1981). "Absence of volatile nitrosamines in human feces". Cancer Res. 41 (10): 3992–4. PMID 7285009.

- ↑ Bingham, SA; Pignatelli, B; Pollock, JR; et al. (March 1996). "Does increased endogenous formation of N-nitroso compounds in the human colon explain the association between red meat and colon cancer?". Carcinogenesis. 17 (3): 515–23. doi:10.1093/carcin/17.3.515. PMID 8631138.

- ↑ Kuhnle, GG; Story, GW; Reda, T; et al. (October 2007). "Diet-induced endogenous formation of nitroso compounds in the GI tract". Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43 (7): 1040–7. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.011. PMID 17761300.