Sabaeans

| Sabaean Kingdom مَمْلَكَة سَبَأ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| between 1200 and 800 BCE–CE 275 | |||||||

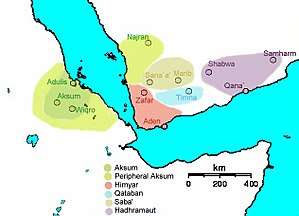

Sabaeans (khaki) in the 3rd century CE | |||||||

| Capital |

Sirwah Ma'rib, Sana'a | ||||||

| Common languages | Sabaic | ||||||

| Religion | pre-Islamic Arabian religions | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Mukarrib | |||||||

• 700–680 BCE | Karibi-ilu | ||||||

• 620–600 BCE | Karib'il Watar | ||||||

• 60–20 BCE | Ilasaros | ||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age to Classical Antiquity | ||||||

• Established | between 1200 and 800 BCE | ||||||

• Disestablished | CE 275 | ||||||

| |||||||

The Sabaeans or Sabeans (Arabic: اَلـسَّبَئِيُّون, as-Saba’iyyūn; Hebrew: שבא; Musnad: 𐩪𐩨𐩱) were an ancient people speaking an Old South Arabian language who lived in the southern Arabian Peninsula.[1]

The kingdom of Saba’ (Arabic: سَـبَـأ)[2][3] has been identified with the biblical land of Sheba.[4][5][6] The view that the biblical kingdom of Sheba was the ancient Semitic civilization of Saba in Southern Arabia is controversial: Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman write that "the Sabaean kingdom began to flourish only from the eighth century BC onward" and that the story of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba is "an anachronistic seventh-century set piece meant to legitimize the participation of Judah in the lucrative Arabian trade."[7] The British Museum states that there is no archaeological evidence for such a queen but that the kingdom described as hers was Saba, "the oldest and most important of the South Arabian kingdoms".[8] Kenneth Kitchen dates the kingdom to between 1200 BCE until 275 CE, with its capital Ma'rib.[9] The Kingdom fell after a long but sporadic civil war between several Yemenite dynasties claiming kingship;[10][11] from this the late Himyarite Kingdom arose as victors.

Sabaeans are mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. In the Quran they are described as either the people of Saba’,[2][3] or as People of Tubba' qawm Ṭubba‘ (Arabic: قَـوْم تُـبَّـع[12][13]).[14]

History

The origin of the Sabaean Kingdom is uncertain. Kenneth Kitchen dates the kingdom to around 1200 BCE,[15] while Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman write that "the Sabaean kingdom began to flourish only from the eighth century BCE onward",[16] and Jan Ratso writes that there is "hardly any evidence" for such a kingdom until the ninth or eight century.[17] Originally, the Sabaeans were one of the sha`bs, "communities", on the edge of the Sayhad desert. Very early, at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC, the political leaders ( 'mlk) of this tribal community managed to create a huge commonwealth of sha`bs occupying most of South Arabian territory, and took the title mkrb SB', "mukarrib of the Sabaeans".[18]

Several factors caused a significant decline of the Sabaean state and civilization by the end of the 1st millennium BC.[19] Saba' was conquered by the Himyarite Kingdom in the first century BCE; but after the disintegration of the first Himyarite Kingdom of the Kings of Saba' and Dhū Raydān, the Middle Sabaean Kingdom reappeared in the early second century.[20] The Sabaean kingdom was finally conquered by the Ḥimyarites in the late 3rd century and at that time the capital was Ma'rib. It was located along the strip of desert called Sayhad by medieval Arab geographers, which is now named Ramlat al-Sab'atayn.

The Sabaean people were a South Arabian people. Each of these peoples had regional kingdoms in ancient Yemen, with the Minaeans in the north in Wādī al-Jawf, the Sabeans on the southwestern tip, stretching from the highlands to the sea; the Qatabānians to the east of them, and the Ḥaḑramites east of them.

The Sabaeans, like the other Yemenite kingdoms of the same period, were involved in the extremely lucrative spice trade, especially frankincense and myrrh.[21]

They left behind many inscriptions in the monumental ancient South Arabian script or Musnad, as well as numerous documents in the related cursive Zabūr script.

In the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, Augustus claims that:

By my command and under my auspices two armies were led at about the same time into Ethiopia and into Arabia, which is called the Blessed [?]. Great forces of each enemy people were slain in battle and several towns captured. In Ethiopia the advance reached the town of Nabata, which is close to Meroe; in Arabia the army penetrated as far as the territory of the Sabaeans and the town of Ma'rib.[22]

Religious practices

Muslim writer Muhammad Shukri al-Alusi compares their religious practices to Islam in his Bulugh al-'Arab fi Ahwal al-'Arab:[23]

The Arabs during the pre-Islamic period used to practice certain things that were included in the Islamic Sharia. They, for example, did not marry both a mother and her daughter. They considered marrying two sisters simultaneously to be a most heinous crime. They also censured anyone who married his stepmother, and called him dhaizan. They made the major hajj and the minor umra pilgrimage to the Ka'ba, performed the circumlocution around the Ka'ba tawaf, ran seven times between Mounts Safa and Marwa sa'y, threw rocks and washed themselves after sexual intercourse. They also gargled, sniffed water up into their noses, clipped their fingernails, removed all pubic hair and performed ritual circumcision. Likewise, they cut off the right hand of a thief and stoned Adulterers

— Muhammad Shukri al-Alusi, Bulugh al-'Arab fi Ahwal al-'Arab, Vol. 2, p. 122

A late Arabic writer wrote of the Sabaeans that they had seven temples dedicated to the seven planets, which they considered as intermediaries to be used in their relation to God. Each of these temples had a characteristic geometric shape, a characteristic color, and an image made of one of the seven metals. They had two sects, star and idol worshippers, and the former doctrine was similar to one that come from Hermes Trismegistus.[24]

Biblical references

Sabaeans are mentioned in the biblical books of Job, Joel, Ezekiel, and Isaiah. The Book of Job mentions them as having slayed Job's livestock and servants.[25] In Isaiah they are described as "tall of stature".[26]

Mentions in the Quran

The Sabaeans are mentioned in the Qur'an twice as Qawm Saba’ (Arabic: قَـوْم سَـبَـأ, people of Saba). The Qur'an mentions the kingdom of the Saba in the 34th Chapter. The Qur'anic narrative, from sura 27 (An-Naml),[5] has Suleiman (Solomon) getting reports from the Hoopoe bird about the kingdom of Saba, ruled by a queen whose people worship the sun instead of God. Suleiman (Solomon) sends a letter inviting her to submit fully to the One God, Allah, Lord of the Worlds, according to the Islamic text. The Queen of Saba is unsure how to respond and asks her advisors for counsel. They reply by reminding her that they are "of great toughness" in a reference to their willingness to go to war should she choose to. She replies that she fears if they were to lose, Suleiman may behave as any other king would: 'entering a country, despoiling it and making the most honorable of its people its lowest'. She decides to meet with Suleiman in order to find out more. Suleiman receives her response to meet him and asks if anyone can bring him her throne before she arrives. A jinn under the control of Suleiman proposed that he will bring it before Suleiman rises from his seat. One who had knowledge of the "Book" proposed to bring him the throne of Bilqis 'in the twinkling of an eye' and accomplished that immediately.[6] The queen arrives at his court, is shown her throne and asked: does your throne look like this? She replied: (It is) as though it were it. When she enters his crystal palace she accepts Abrahamic monotheism and the worship of one God alone, Allah.

Rulers

See also

References

- ↑ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity, 1991.

- 1 2 Quran 27:6–93

- 1 2 Quran 34:15–18

- ↑ Robert D. Burrowes (2010). Historical Dictionary of Yemen. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 319. ISBN 0810855283.

- ↑ St. John Simpson (2002). Queen of Sheba: treasures from ancient Yemen. British Museum Press. p. 8. ISBN 0714111511.

- ↑ Kenneth Anderson Kitchen (2003). On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 116. ISBN 0802849601.

- ↑ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman, David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition p. 171

- ↑ "The kingdoms of ancient South Arabia". Britishmuseum.org. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved 2013-02-22.

- ↑ Kenneth A. Kitchen : The World of "Ancient Arabia" Series. Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Part I. Chronological Framework and Historical Sources p.110

- ↑ D. H. Muller, 1891; Mordtmann, Himyarische Inschriften, 1893, p. 53

- ↑ Javad Ali, The Articulate in the History of Arabs before Islam, Volume 2, p. 420

- ↑ Quran 44:37 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- ↑ Quran 50:12–14

- ↑ Brannon M. Wheeler (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 166. ISBN 0-8264-4956-5.

- ↑ Kenneth A. Kitchen : The World of "Ancient Arabia Series. Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Part I. Chronological Framework and Historical Sources, p.110

- ↑ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman, David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition, p. 171

- ↑ Retso, Jan (2002). The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads. Routledge. p. 175. ISBN 978-0700716791.

- ↑ Andrey Korotayev. Pre-Islamic Yemen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1996. ISBN 3-447-03679-6. P. 2-3.

- ↑ Andrey Korotayev. Ancient Yemen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-19-922237-1. P. 98.

- ↑ Andrey Korotayev. Pre-Islamic Yemen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1996. ISBN 3-447-03679-6.

- ↑ Yemen

- ↑ Res Gestae Divi Augusti, paragraph 26.5, translation from Wikisource

- ↑ al-Alusi, Muhammad Shukri. Bulugh al-'Arab fi Ahwal al-'Arab, Vol. 2. p. 122.

- ↑ Stapleton, H. E.; R. F. Azo; M. H. Husein (1927). Chemistry in Iraq and Persia in the Tenth Century AD: Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 8. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society of Bengal. pp. 398–403.

- ↑ Job 1:14-15

- ↑ Isaiah 45:14

- Bafaqīh, M. ‛A., L'unification du Yémen antique. La lutte entre Saba’, Himyar et le Hadramawt de Ier au IIIème siècle de l'ère chrétienne. Paris, 1990 (Bibliothèque de Raydan, 1).

- Andrey Korotayev. Ancient Yemen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-19-922237-1 .

- Andrey Korotayev. Pre-Islamic Yemen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1996. ISBN 3-447-03679-6.

- Ryckmans, J., Müller, W. W., and ‛Abdallah, Yu., Textes du Yémen Antique inscrits sur bois. Louvain-la-Neuve, 1994 (Publications de l'Institut Orientaliste de Louvain, 43).

- Info Please

- Article at Encyclopædia Britannica

External links

- S. Arabian "Inscription of Abraha" in the Sabaean language, at Smithsonian/NMNH website