Book of Joel

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bible portal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Book of Joel is part of the Hebrew Bible. Joel is part of a group of twelve prophetic books known as the Twelve Minor Prophets. (The term indicates the short length of the text in relation to longer prophetic texts known as the Major Prophets.)

Content

After a superscription ascribing the prophecy to Joel (son of Pethuel), the book may be broken down into the following sections:

- Lament over a great locust plague and a severe drought (1:1–2:17).

- The effects of these events on agriculture, farmers, and on the supply of agricultural offerings for the Temple in Jerusalem, interspersed with a call to national lament (1:1–20).

- A more apocalyptic passage comparing the locusts to an army, and revealing that they are God’s army (2:1–11).

- A call to national repentance in the face of God's judgment (2:12–17).

- Promise of future blessings (2:18–32 or 2:18–3:5).

- Banishment of the locusts and restoration of agricultural productivity as a divine response to national penitence (2:18–27).

- Future prophetic gifts to all God’s people, and the safety of God’s people in the face of cosmic cataclysm (2:28–32 or 3:1–5).

- Coming judgment on God's (Israel's) enemies and the vindication of Israel (3:1–21 or 4:1–21).

(Note: the Book of Joel's division verses differs greatly between editions of the Bible; some editions have three chapters, others four.[1])

Historical context

As there are no explicit references in the book to datable persons or events, scholars have assigned a wide range of dates to the book. The main positions are:[2]

- Ninth century BC, particularly in the reign of Joash – a position especially popular among nineteenth-century scholars (making Joel one of the earliest writing prophets)

- Early eighth century BC, during the reign of Uzziah (contemporary with Hosea, Amos, and Jonah)[3]

- c. 630–587 BC, in the last decades of the kingdom of Judah (contemporary with Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Habakkuk)

- c. 520–500 BC, contemporary with the return of the exiles and the careers of Zechariah and Haggai.

- The decades around 400 BC, during the Persian period (making him one of the latest writing prophets)

Evidence produced for these positions are allusions in the book to the wider world, similarities with other prophets, and linguistic details. Other commentators, such as John Calvin,[4] attach no great importance to the precise dating.

History of interpretation

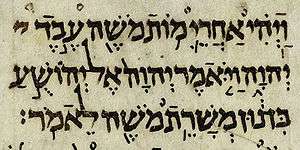

The Masoretic text places Joel between Hosea and Amos (the order inherited by the Tanakh and Old Testament), while the Septuagint order is Hosea–Amos–Micah–Joel–Obadiah–Jonah. The Hebrew text of Joel seems to have suffered little from scribal transmission, but is at a few points supplemented by the Septuagint, Syriac, and Vulgate versions, or by conjectural emendation.[5] While the book purports to describe a plague of locusts, some ancient Jewish opinion saw the locusts as allegorical interpretations of Israel's enemies.[6] This allegorical interpretation was applied to the church by many church fathers. Calvin took a literal interpretation of chapter 1, but allegorical view of chapter 2, a position echoed by some modern interpreters. Most modern interpreters, however, see Joel speaking of a literal locust plague given a prophetic/ apocalyptic interpretation.[7]

The traditional ascription of the whole book to the prophet Joel was challenged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by a theory of a three-stage process of composition: 1:1–2:27 were from the hand of Joel, and dealt with a contemporary issue; 2:28–3:21/3:1–4:21 were ascribed to a continuator with an apocalyptic outlook. Mentions in the first half of the book to the day of the Lord were also ascribed to this continuator. 3:4–8/4:4–8 could be seen as even later. Details of exact ascriptions differed between scholars.

This splitting of the book’s composition began to be challenged in the mid-twentieth century, with scholars defending the unity of the book, the plausibility of the prophet combining a contemporary and apocalyptic outlook, and later additions by the prophet. The authenticity of 3:4–8 has presented more challenges, although a number of scholars still defend it.[8]

Biblical quotes and allusions

There are many parallels of language between Joel and other Old Testament prophets. They may represent Joel’s literary use of other prophets, or vice versa.

In the New Testament, his prophecy of the outpouring of God′s Holy Spirit upon all people was notably quoted by Saint Peter in his Pentecost sermon.[9]

The table below represents some of the more explicit quotes and allusions between specific passages in Joel and passages from the Old and New Testaments.

| Joel | Old Testament | New Testament |

|---|---|---|

| 1:6, 2:2–10 | Revelation 9:3, 7–9 | |

| 1:15 | Isaiah 13:6 Ezekiel 30:2–3 |

|

| 2:1 | Zephaniah 1:14–16 | |

| 2:1–2 | Amos 5:18, 20 | |

| 2:11 | Malachi 3:2 | |

| 2:14 | Jonah 3:9 | |

| 2:20–21 | Psalm 126:2–3 | |

| 2:27 | Isaiah 45:5 Ezekiel 36:11 |

|

| 2:28–32/3:1–5 | Acts 2:16–21 | |

| 2:31/3:4 | Malachi 3:23/4:5 | |

| 2:32/3:5 | Obadiah 17 | Romans 10:13 |

| 3:1/4:1 | Psalm 126:1 | |

| 3:10/4:10 | Isaiah 2:4 Micah 4:3 |

|

| 3:16/4:16 | Amos 1:2 | |

| 3:17/4:17 | Obadiah 17 | |

| 3:18/4:18 | Amos 9:13 |

Plange quasi virgo, the third responsory for Holy Saturday, is loosely based on some verses of the Book of Joel.

References

- ↑ Hayes, Christine (2006). "Introduction to the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible) – Lecture 23 – Visions of the End: Daniel and Apocalyptic Literature". Open Yale Courses. Yale University.

- ↑ Outlined by Allen (pp. 19–25), who himself favours the fourth position, with the second position (early eight century) added from Patterson (pp. 231–32).

- ↑ Patterson, Richard D. The Expositor's Bible Commentary, vol. 7. Zondervan.

- ↑ Cited in Allen, p. 19, although Calvin did lean toward a later dating

- ↑ Allen 36

- ↑ Targum at 2:25; also margin of LXX manuscript Q, mid-6th century AD

- ↑ See Allen 29–31

- ↑ See Allen 25–29 for details and arguments.

- ↑ Acts 2

Further reading

See also works on the Minor Prophets as a whole.

- Achtemeier, Elizabeth. Minor Prophets I. New International Biblical Commentary. (Hendrickson, 1999)

- Ahlström, Gösta W. Joel and the Temple Cult of Jerusalem. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 21. (Brill, 1971)

- Allen, Leslie C. The Books of Joel, Obadiah, Jonah & Micah. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. (Eerdmans, 1976)

- Anders, Max E. & Butler, Trent C. Hosea–Micah. Holman Old Testament Commentary. (B&H Publishing, 2005)

- Assis, Elie. Joel: A Prophet Between Calamity and Hope (LHBOTS, 581), New York: Bloomsbury, 2013

- Baker, David W. Joel, Obadiah, Malachi. NIV Application Commentary. (Zondervan, 2006)

- Barton, John. Joel & Obadiah: a Commentary. Old Testament Library. (Westminster John Knox, 2001)

- Birch, Bruce C. Hosea, Joel & Amos. Westminster Bible Companion. (Westminster John Knox, 1997)

- Busenitz, Irvin A. Commentary on Joel and Obadiah. Mentor Commentary. (Mentor, 2003)

- Calvin, John. Joel, Amos, Obadiah. Calvin’s Bible Commentaries. (Forgotten Books, 2007)

- Coggins, Richard. Joel and Amos. New Century Bible Commentary. (Sheffield Academic Press, 2000)

- Crenshaw, James L. Joel: a New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. The Anchor Bible. (Yale University Press, 1995)

- Finley, Thomas J. Joel, Amos, Obadiah: an Exegetical Commentary. (Biblical Studies Press, 2003)

- Gæbelein, Frank E. (ed) Daniel and the Minor Prophets. The Expositor's Bible Commentary, Volume 7. (Zondervan, 1985)

- Garrett, Duane A. Hosea, Joel. The New American Commentary. (B&H Publishing, 1997)

- Hubbard, David Allen. Joel and Amos: an Introduction and Commentary. Tyndale Old Testament Commentary. (Inter-Varsity Press, 1990)

- Limburg, James. Hosea–Micah. Interpretation – a Bible Commentary for Teaching & Preaching. (Westminster John Knox, 1988)

- Mason, Rex. Zephaniah, Habakkuk, Joel. Old Testament Guides. (JSOT Press, 1994)

- McQueen, Larry R.M. Joel and the Spirit: the Cry of a Prophetic Hermeneutic. (CTP, 2009)

- Ogden, Graham S. & Deutsch, Richard R. A Promise of Hope – a Call to Obedience: a Commentary on the Books of Joel & Malachi. International Theological Commentary (Eerdmans/ Hansel, 1987)

- Ogilvie, John Lloyd. Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah. Communicator's Commentary 20. (Word, 1990)

- Price, Walter K. The Prophet Joel and the Day of the Lord. (Moody, 1976)

- Prior, David. The Message of Joel, Micah, and Habakkuk: Listening to the Voice of God. The Bible Speaks Today. (Inter-Varsity Press, 1999)

- Pohlig, James N. An Exegetical Summary of Joel. (SIL International, 2003)

- Roberts, Matis (ed). Trei asar : The Twelve Prophets: a New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic, and Rabbinic Sources. Vol. 1: Hosea. Joel. Amos. Obadiah. (Mesorah, 1995)

- Robertson, O. Palmer. Prophet of the Coming Day of the Lord: the Message of Joel. Welwyn Commentary. (Evangelical Press, 1995)

- Simkins, Ronald. Yahweh's Activity in History and Nature in the Book of Joel. Ancient Near Eastern Texts & Studies 10 (E. Mellen Press, 1991)

- Simundson, Daniel J. Hosea–Micah. Abingdon Old Testament Commentaries. (Abingdon, 2005)

- Stuart, Douglas. Hosea–Jonah. Word Biblical Commentary 31. (Word, 1987)

- Sweeney, Marvin A. The Twelve Prophets, Vol. 1: Hosea–Jonah. Berit Olam – Studies in Hebrew Narrative & Poetry. (Liturgical Press, 2000)

- Wolff, Hans Walter. A Commentary on the Books of the Prophets Joel & Amos. Hermeneia – a Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. (Augsburg Fortress, 1977)

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Book of Joel

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Joel

- Jewish translations:

- Yoel – Joel (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV)

- Joel at The Great Books (New Revised Standard Version)

- Joel at BibleGateway (New International Version and others)

- Joel at BlueLetter Bible (King James Version and others, plus commentaries)

Book of Joel | ||

| Preceded by Hosea |

Hebrew Bible | Succeeded by Amos |

| Christian Old Testament | ||