Frankincense

Frankincense (also known as olibanum, Hebrew: לבונה [levona], Arabic: al-lubān) is an aromatic resin used in incense and perfumes, obtained from trees of the genus Boswellia in the family Burseraceae, particularly Boswellia sacra (syn: B. bhaw-dajiana), B. carterii33, B. frereana, B. serrata (B. thurifera, Indian frankincense), and B. papyrifera. The word is from Old French franc encens ("high-quality incense").[1]

There are five main species of Boswellia that produce true frankincense. Resin from each of the four is available in various grades, which depend on the time of harvesting. The resin is then hand-sorted for quality.

Etymology

The English word frankincense is derived from the Old French expression franc encens, meaning "high-quality incense". The word franc in Old French meant "noble" or "pure".[2]

A popular folk etymology suggests a connection with the Franks (the forefathers of some French and Germans), who reintroduced the spice to Western Europe during the Middle Ages, but the word itself comes from the expression.[2][3]

Description

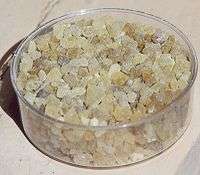

Frankincense is tapped from the scraggy but hardy trees by slashing the bark, which is called striping, and allowing the exuded resin to bleed out and harden. These hardened resins are called tears. There are several species and varieties of frankincense trees, each producing a slightly different type of resin. Differences in soil and climate create even more diversity of the resin, even within the same species. Boswellia sacra trees are considered unusual for their ability to grow in environments so unforgiving that they sometimes grow out of solid rock. The initial means of attachment to the rock is unknown, but is accomplished by a bulbous disk-like swelling of the trunk. This growth prevents it from being ripped from the rock during violent storms. This feature is slight or absent in trees grown in rocky soil or gravel. The trees start producing resin when they are about eight to 10 years old.[4] Tapping is done two to three times a year with the final taps producing the best tears due to their higher aromatic terpene, sesquiterpene and diterpene content. Generally speaking, the more opaque resins are the best quality. Fine resin is produced in Somalia, from which the Roman Catholic Church purchases most of its stock.[5]

Recent studies have indicated that frankincense tree populations are declining, partly due to over-exploitation.[6] Heavily tapped trees produce seeds that germinate at only 16% while seeds of trees that had not been tapped germinate at more than 80%. In addition, burning, grazing, and attacks by the longhorn beetle have reduced the tree population.[7] Conversion (clearing) of frankincense woodlands to agriculture is also a major threat.[8]

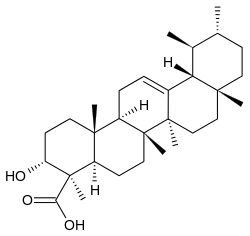

Chemical composition

These are some of the chemical compounds present in frankincense:

- acid resin (56 %), soluble in alcohol and having the formula C20H32O4[9]

- gum (similar to gum arabic) 30–36%[9]

- 3-acetyl-beta-boswellic acid (Boswellia sacra)[10]

- alpha-boswellic acid (Boswellia sacra)[10]

- 4-O-methyl-glucuronic acid (Boswellia sacra)[10]

- incensole acetate, C21H34O3[11]

- phellandrene[9]

- (+)-cis- and (+)-trans-olibanic acids[12]

See also for example the following references which give a comprehensive overview on the chemical compounds present in different frankincense species.[13][14]

History

Frankincense has been traded on the Arabian Peninsula for more than 6,000 years.[15] [16] A mural depicting sacks of frankincense traded from the Land of Punt adorns the walls of the temple of ancient Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut, who died circa 1458 BC.[17]

Frankincense was one of the consecrated incenses (ha-ketoret) described in the Hebrew Bible and Talmud used in ketoret ceremonies, an important component of the services in the Temple in Jerusalem.[18] It was offered on a specialized incense altar in the time when the Tabernacle was located in the First and Second Temples. It is mentioned in the Book of Exodus 30:34, where it is named לבונה (levona; Biblical Hebrew: lebonah), similar to לבן, lavan, 'white'.[18] It was one of the ingredients in the perfume of the sanctuary (Exodus 30:34), and was used as an accompaniment of the meal-offering (Leviticus 2:1, 2:16, 6:15, 24:7). It was also mentioned as a commodity in trade from Sheba (Isaiah 60:6 ; Jeremiah 6:20). When burnt it emitted a fragrant odor, and the incense was a symbol of the Divine name (Malachi 1:11 ; Song of Solomon 1:3) and an emblem of prayer (Psalm 141:2). It was often associated with myrrh (Song of Solomon 3:6, 4:6). A specially "pure" kind, lebhonah zakkah, was presented with the showbread (Leviticus 24:7).[19]

Frankincense also received numerous mentions in the New Testament (Luke 1:10 ; Revelation 5:8, 8:3). Together with gold and myrrh, it was made an offering to the infant Jesus (Matthew 2:11). Frankincense is a symbol of holiness and righteousness. The gift of frankincense to the Christ child was symbolic of his willingness to become a sacrifice, wholly giving himself up, analogous to a burnt offering.

Frankincense was reintroduced to Europe by Frankish Crusaders, although its name refers to its quality, not to the Franks themselves.[1] Although it is better known as "frankincense" to westerners, the resin is also known as olibanum, or in Arabic al-lubān (لبان, roughly translated: "that which results from milking"), a reference to the milky sap tapped from the Boswellia tree.

The Greek historian Herodotus was familiar with frankincense and knew it was harvested from trees in southern Arabia. He reported that the gum was dangerous to harvest because of venomous snakes that lived in the trees. He goes on to describe the method used by the Arabs to get around this problem, that being the burning of the gum of the styrax tree whose smoke would drive the snakes away.[20] The resin is also mentioned by Theophrastus and by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia.

Southern Arabia was a major exporter of frankincense in antiquity, with some of it being traded as far as China. The 13th-century Chinese writer and customs inspector Zhao Rugua wrote on the origin of frankincense, and of its being traded to China:

"Ruxiang or xunluxiang comes from the three Dashi [Arab] countries of Murbat (Maloba), Shihr (Shihe), and Dhofar (Nufa), from the depths of the remotest mountains.[21] The tree which yields this drug may generally be compared to the pine tree. Its trunk is notched with a hatchet, upon which the resin flows out, and, when hardened, turns into incense, which is gathered and made into lumps. It is transported on elephants to the Dashi (on the coast), who then load it upon their ships to exchange it for other commodities in Sanfoqi. This is the reason why it is commonly collected at and known as a product of Sanfoqi."[22]

Quality

Frankincense comes in many types, and its quality is based on color, purity, aroma, age, and shape. Silver and Hojari are generally considered the highest grades of frankincense.

Currently, there are two dissertations which may enable the identification of a few olibanum species according to their specific secondary metabolism products.[13][14]

Production

Estimates of the current annual world production of frankincense vary, but generally are around several thousands tonnes. More than 82% of the product comes from Somalia, with some frankincense also gathered in adjacent Southern Arabia and Ethiopia, Sudan, and other central African countries.

In Somalia, frankincense is harvested in the Sanaag and Bari regions: mountains lying at the northwest of Erigavo; El Afweyn District; Cal Madow mountain range, a westerly escarpment that runs parallel to the coast; Cal Miskeed, a middle segment of the frankincense-growing escarpment; Karkaar mountains or eastern escarpment, which lies at the eastern fringe of the frankinscence escarpment.[23][6]

In Dhofar, Oman, frankincense species grow north of Salalah and were traded in the ancient coastal city of Sumhuram, now Khor Rori[24].

Uses

Frankincense is used in perfumery and aromatherapy. It is also an ingredient that is sometimes used in skincare. The essential oil is obtained by steam distillation of the dry resin. Some of the smells of the frankincense smoke are products of pyrolysis.

In Chinese medicine, it (ru xiang) along with myrrh (mo yao) have anti-bacterial properties as well as blood-moving uses. It can be used topically or orally. The Egyptians cleansed body cavities in the mummification process with frankincense and natron. In Persian medicine, it is used for diabetes.[25]

Frankincense is used in many Christian churches, including the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Catholic churches. According to the Biblical text of Matthew 2:11, gold, frankincense, and myrrh were among the gifts to Jesus by the biblical magi "from out of the East." Christian and Islamic Abrahamic faiths have all used frankincense mixed with oils to anoint newborn infants, initiates and members entering into new phases of their spiritual lives.

Conversely, the spread of Christianity depressed the market for frankincense during the 4th century AD. Desertification made the caravan routes across the Rub' al-Khali ("Empty Quarter") of the Arabian Peninsula more difficult. Additionally, increased raiding by the Parthians in the Near East caused the frankincense trade to dry up after A.D. 300.

Essential oil

The essential oil of frankincense is produced by steam distillation of the tree resin. The oil's chemical components are 75% monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, monoterpenoles, sesquiterpenols and ketones. It has a good balsamic sweet fragrance, while the Indian frankincense oil has a very fresh smell. Contrary to what some commercial entities claim, steam or hydro distilled frankincense oils do not contain boswellic acids (triterpenoids), although may be present in trace quantities in the solvent extracted products. The chemistry of the essential oil is mainly monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, such as alpha-pinene, Limonene, alpha-Thujene, and beta-Pinene with small amounts of diterpenoid components being the upper limit in terms of molecular weight.[26][27][28][29]

Perfume

Olibanum is characterised by a balsamic-spicy, slightly lemon, fragrance of incense, with a conifer-like undertone. It is used in the perfume, cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries.

See also

- Desi Sangye Gyatso

- Elemi, tree

- Frankincense Trail, Oman

- Incense Route, a large network around the Mediterranean and beyond

- Myrrh

- Nabataeans

- Palo santo, tree

- Pliny the Elder

- Resin

- Theophrastus

Notes

- 1 2 Oxford English Dictionary.

- 1 2 "Frankincense". Etymology Online. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ↑ "Frank". Etymology Online. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ↑ "Omani World Heritage Sites". www.omanwhs.gov.om. Archived from the original on 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ↑ BBC.co.uk

- 1 2 Patinkin, Jason (25 December 2016). "World's last wild frankincense forests are under threat". Yahoo Finance. Associated Press. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ↑ Melina, Remy (December 21, 2011). "Christmas Staple Frankincense 'Doomed,' Ecologists Warn". LiveScience.

- ↑ Dejenea, T.; Lemenih, M.; Bongers, F. (February 2013). "Manage or convert Boswellia woodlands? Can frankincense production payoff?". Journal of Arid Environments. 89: 77–83. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2012.09.010.

- 1 2 3 "Olibanum.—Frankincense". Henriette's Herbal Homepage. www.henriettes-herb.com. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- 1 2 3 "Farmacy Query". www.ars-grin.gov. Archived from the original on 2004-11-10. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ↑ Incensole acetate (@NIST)

- ↑ Cerutti-Delasalle, Celine (4 October 2016). "The (+)-cis- and (+)-trans-Olibanic Acids: Key Odorants of Frankincense". Angewandte Chemie. doi:10.1002/anie.201605242. ISSN 1521-3773.

- 1 2 Chemotaxonomic Investigations on Resins of the Frankincense Species Boswellia papyrifera, Boswellia serrata and Boswellia sacra, respectively, Boswellia carterii: A Qualitative and Quantitative Approach by Chromatographic and Spectroscopic Methodology, Paul, M., Dissertation, Saarland University (2012) http://scidok.sulb.uni-saarland.de/volltexte/2012/4999/pdf/Dissertation_Fertig_211112.pdf

- 1 2 Phytochemical Investigations on Boswellia Species, Basar, S., Dissertation, Hamburg University (2005) http://www.chemie.uni-hamburg.de/bibliothek/2005/DissertationBasar.pdf

- ↑ Paper on Chemical Composition of Frankincense Archived 2008-12-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Ulric Killion, A Modern Chinese Journey to the West: Economic Globalisation And Dualism, (Nova Science Publishers: 2006), p.66

- ↑ "Queen Hatshepsut's expedition to the Land of Punt: The first oceanographic cruise?". Dept. of Oceanography, Texas A&M University. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- 1 2 Klein, Ernest, A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the Hebrew Language for Readers of English, The University of Haifa, Carta, Jerusalem, p.292

- ↑ "www.Bibler.org - Dictionary - Frankincense". 2012-07-21.

- ↑ Herodotus 3,107

- ↑ Kauz, Ralph (2010). Ralph Kauz, ed. Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea. Volume 10 of East Asian Economic and Socio-cultural Studies - East Asian Maritime History. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 130. ISBN 3-447-06103-0. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

The frankincense was first collected in the Hadhramaut ports of Mirbat, Shihr, and Zufar whence Arab merchant vessels shipped it to Srivijaya, before it was then reexported to China. The term "xunluxiang" is derived from the Arab word "kundur". . . According to Li Xun, frankincense originally came from Persia.92 Laufer refers to the Xiangpu 香譜 by Hong Chu . . . Zhao Rugua notes: Ruxiang or xunluxiang comes from the three Dashi countries of Murbat (Maloba), Shihr (Shihe), and Dhofar (Nufa), from the depths of the remotest mountains. The tree which yields this drug may generally be compared to the pine tree. Its trunk is notched with a hatchet, upon which the

- ↑ Kauz, Ralph (2010). Ralph Kauz, ed. Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea. Volume 10 of East Asian Economic and Socio-cultural Studies - East Asian Maritime History. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 131. ISBN 3-447-06103-0. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

resin flows out, and, when hardened, turns into incense, which is gathered and made into lumps. It is transported on elephants to the Dashi (on the coast), who then load it upon their ships to exchange it for other commodities in Sanfoqi. This is the reason why it is commonly collected at and known as a product of Sanfoqi.94

- ↑ War-Torn Societies Project International, Somali Programme (2001). Rebuilding Somalia: Issues and possibilities for Puntland. London: HAAN. p. 124. ISBN 1874209049.

- ↑ Coppi, Andrea; Cecchi, Lorenzo; Selvi, Federico; Raffaelli, Mauro (2010-03-18). "The Frankincense tree (Boswellia sacra, Burseraceae) from Oman: ITS and ISSR analyses of genetic diversity and implications for conservation". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 57 (7): 1041–1052. doi:10.1007/s10722-010-9546-8. ISSN 0925-9864.

- ↑ "The Effects of Boswellia serrata Gum Resin on the Blood Glucose and Lipid Profile of Diabetic Patients: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial". doi:10.1177/2515690X18772728. PMID 29774768.

- ↑ Verghese, J.; et al. (1987). "A Fresh Look at the Constituents of Indian Olibanum Oil". Flav. Fragr. J. 2 (3): 99–102. doi:10.1002/ffj.2730020304.

- ↑ Hayashi, S.; Amemori, H.; Kameoka, H.; Hanafusa, M.; Furukawa, K. (1998). "Comparison of Volatile Compounds from Olibanum from Various Countries". J. Essent. Oil Res. 10: 25–30. doi:10.1080/10412905.1998.9700833.

- ↑ Baser, S., Koch, A., Konig, W.A. (2001). "A Verticillane-type diterpene from Boswellia carterii Essential Oil". Flav. Frag" J 16, 315-318

- ↑ Frank, A; Unger, M. (Apr 2006). "Analysis of frankincense from various Boswellia species with inhibitory activity on human drug metabolising cytochrome P450 enzymes using liquid chromatography mass spectrometry after automated on-line extraction". J Chromatogr A. 1112 (1–2): 255–62. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2005.11.116.

References

- Woolley, CL; et al. (Oct 2012). "Chemical differentiation of Boswellia sacra and Boswellia carterii essential oils by gas chromatography and chiral gas chromatography-mass spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography A. 1261: 158–63. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2012.06.073.

- Bibliography

- Müller, Walter W.: Weihrauch : ein arabisches Produkt und seine Bedeutung in der Antike, Realencyclopaedie / Pauly-Wissowa : Supp. ; 15, 1978, 700-777.

- Groom, Nigel (1981). Frankincense & Myrrh: A Study of the Arabian Incense Trade. ISBN 0-86685-593-9.

- Maloney, George A, (1997). Gold, Frankincense, and Myrrh: An Introduction to Eastern Christian Spirituality. ISBN 0-8245-1616-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frankincense. |

.jpg)