Quba Mosque

| Quba Mosque | |

|---|---|

Quba Mosque in Medina | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Medina, Saudi Arabia |

| Geographic coordinates | 24°26′21″N 39°37′02″E / 24.43917°N 39.61722°ECoordinates: 24°26′21″N 39°37′02″E / 24.43917°N 39.61722°E |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Province | Al Madinah |

| Region | Hejaz |

| Architectural description | |

| Architectural type | Mosque |

| Completed | 622 |

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | 6 |

| Minaret(s) | 4 |

The Quba Mosque (Arabic: مَـسْـجِـد قُـبَـاء, translit. Masjid Qubā’) is a mosque in the outlying environs of Medina, Saudi Arabia. Depending on whether the Mosque of the Companions in the Eritrean city of Massawa[1] is older or not, it may be the first mosque in the world that dates to the lifetime of the Islamic Nabī (Arabic: نَـبِي, Prophet) Muhammad in the 7th century CE, and depending on whether the religion of Islam started with him[2] or preceded him,[3][4][5] it is either the first mosque in the history of Islam,[6] or it is not the first,[7] with the Great Mosques of Mecca[8][9][10] and Jerusalem[11][12] being older, due to their association with earlier Prophets in Islam, especially Abraham.[13][14][15] According to legend, its first stones were positioned by Muhammad as soon as he arrived on his emigration from the city of Mecca to Medina,[6] and the mosque was completed by his companions. Muhammad spent 14 days in this mosque praying qaṣr (Arabic: قَـصْـر, a short prayer) while waiting for Ali to arrive in Medina after the latter stayed behind in Mecca to carry out a couple of tasks entrusted to him by the Prophet.

According to Islamic tradition, performing Wuḍū’ (Arabic: وُضُـوء, 'Ablution') in one's home then offering two Rakaʿāṫ (Arabic: رَكَـعَـات) of Nafl (Arabic: نَـفْـل, Optional) prayers in the Quba Mosque is equal to performing one ‘Umrah (Arabic: عُـمْـرَة). Muhammad used to go there, riding or on foot, every Saturday and offer a two rakaʿāt prayer. He advised others to do the same, saying, "Whoever makes ablutions at home and then goes and prays in the Mosque of Quba, he will have a reward like that of an 'Umrah." This ḥadīth (Arabic: حَـدِيـث) was reported by Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Al-Nasa'i, Ibn Majah and Hakim al-Nishaburi.

Architecture

When Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil was commissioned, in the 20th century, to conceive a larger mosque, he intended to incorporate the old structure into his design. But the old mosque was torn down and replaced with a new one.[16]

The new mosque consists of a rectangular prayer hall raised on a second story platform. The prayer hall connects to a cluster containing residential areas, offices, ablution facilities, shops and a library.

Six additional entrances are dispersed on the northern, eastern and western façades. Four minarets mark the corners of the prayer hall. The minarets rest on square bases, have octagonal shafts which take on a circular shape as they reach the top.

Prayer hall

The prayer hall is arranged around a central courtyard, characterised by six large domes resting on clustered columns. A portico, which is two bays in depth, borders the courtyard on the east and west, while a one-bayed portico borders it on the north, and separates it from the women's prayer area.

The women's prayer area, which is surrounded by a screen, is divided into two parts as a passageway connects the northern entrance with the courtyard.

When Quba Mosque was rebuilt in 1986, the Medina architecture was retained - ribbed white domes, and basalt facing and modest exterior - qualities that recalls Madina's simplicity. The courtyard, is flagged with black, red and white marble. It is screened overhead by day from the scorching heat with shades. Arabesque latticework filters the light of the palm groves outside. Elements of the new building include work by the Egyptian architect Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil and the Stuttgart tensile architect Mahmoud Bodo Rasch,[17] a student of Frei Otto.

Landmarks

- Waterfountain

- Masjid Dirar (previously)

Imams and khateebs

- Sheikh Muhammad Ayyub And Adil

- Sheikh Saleh Al Maghamsi

Mentions

In hadith

The merits of Masjid Quba are mentioned in nineteen Sahih al-Bukhari hadiths; thirteen Sahih Muslim hadiths; two Sunan Abu Dawood hadiths; six Al-Muwatta hadiths.[18]

Muhammad frequented the mosque and prayed there. This is referred to in a number of hadith:

Narrated 'Abdullah bin Dinar: Ibn 'Umar said, "The Prophet used to go to the Mosque of Quba every Saturday (sometimes) walking and (sometimes) riding." 'Abdullah (Ibn 'Umar) used to do the same

Narrated Ibn 'Umar: The Prophet used to go to the Mosque of Quba (sometimes) walking and sometimes riding. Added Nafi (in another narration), "He then would offer two Rakat (in the Mosque of Quba)."

— Collected by Muhammad al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari Volume 2, Book 21, Number 285[20]

In the Qur'an

It is believed to be the mosque which the Qur'an mentions as being founded on piety and devoutness (Masjid al-Taqwa):

Never stand (to pray) there (referring to a place of worship in which the hypocrites had used for harm and disbelief, as mentioned in the previous ayah). A place of worship which was founded upon duty (to Allah) from the first day is more worthy that thou should stand (to pray) therein, wherein are men who love to purify themselves. Allah loveth the purifiers.

Gallery

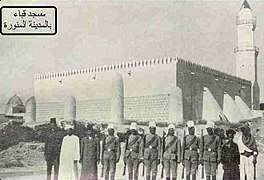

The original mosque, prior to its demolition in the 20th century

The original mosque, prior to its demolition in the 20th century Ditto

Ditto Rear view

Rear view The mosque at dawn

The mosque at dawn

See also

References

- ↑ Reid, Richard J. (12 January 2012). "The Islamic Frontier in Eastern Africa". A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present. John Wiley and Sons. p. 106. ISBN 0470658983. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ Watt, William Montgomery (2003). Islam and the Integration of Society. Psychology Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-415-17587-6.

- ↑ Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 12. ISBN 978-0-19-511234-4.

- ↑ Esposito (2002b), pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Peters, F.E. (2003). Islam: A Guide for Jews and Christians. Princeton University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-691-11553-2.

- 1 2 "Masjid Quba is the first mosque in Islam's history". Masjid Quba'. The Ministry of Hajj, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- ↑ Palmer, A.L. (2016-05-26). Historical Dictionary of Architecture (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 185–236. ISBN 1442263091.

- ↑ Quran 2:127 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- ↑ Quran 3:96 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- ↑ Quran 22:25–37

- ↑ Quran 17:1–7

- ↑ Quran 21:51–82

- ↑ Michigan Consortium for Medieval and Early Modern Studies (1986). Goss, V. P.; Bornstein, C. V., eds. The Meeting of Two Worlds: Cultural Exchange Between East and West During the Period of the Crusades. 21. Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University. p. 208. ISBN 0918720583.

- ↑ Mustafa Abu Sway. "The Holy Land, Jerusalem and Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Qur'an, Sunnah and other Islamic Literary Source" (PDF). Central Conference of American Rabbis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28.

- ↑ Dyrness, W. A. (2013-05-29). Senses of Devotion: Interfaith Aesthetics in Buddhist and Muslim Communities. 7. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 25. ISBN 162032136X.

- ↑ Description of the new mosque and architectural documents at archnet.org Archived January 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ „Alles muss von innen kommen“ - IZ im Gespräch mit dem Stuttgarter Architekten Dr. Rasch, Islamische Zeitung, 6. November 2002

- ↑ Enter Quba Mosque in the "Search the Hadith" box and check off all hadith collections. Archived October 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sahih al-Bukhari, 2:21:284

- ↑ Sahih al-Bukhari, 2:21:285

- ↑ Quran 9:108

- Muhammad: The Messenger of Islam by Hajjah Amina Adil (p. 286)

- The Naqshbandi Sufi Tradition Guidebook of Daily Practices and Devotions by Hisham Kabbani (p. 301)

- Happold: The Confidence to Build by Derek Walker and Bill Addis (p. 81)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Masjid al-Quba. |

- Virtues of Masjid Quba , Madina - Taken from Tafsir Ibn Kathir and other Saheeh Hadith