Seven Sleepers

In Christian and Muslim tradition, the Seven Sleepers (Arabic: اصحاب الکھف, translit. aṣḥāb al kahf, lit. 'People of the Cave') is the story of a group of youths who hid inside a cave outside the city of Ephesus around 250 to escape a religious persecution and emerge 300 years later.

The earliest version of this story comes from the Syrian bishop Jacob of Serugh (c. 450 – 521), which is itself derived from an earlier Greek source, now lost.[2] An outline of this tale appears in Gregory of Tours (538–594), and in Paul the Deacon's (720–799) History of the Lombards.[3] The best-known Western version of the story appears in Jacobus da Varagine's Golden Legend.

The Roman Martyrology mentions the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus under the date of 27 July (June according to Vatican II calendar).[4] The Byzantine calendar commemorates them with feasts on 4 August and 22 October. The ninth-century Irish calendar Félire Óengusso commemorates the Seven Sleepers on 7 August.[5]

The story appears in the Qur'an (Surah Al-Kahf 9–26) and thus is important to Islam. The Quranic story doesn't state the exact number of sleepers, also gives the number of years that they slept as 300 solar years (equivalent to 309 lunar years). The Islamic version includes mention of a dog, al Rakim, who accompanied the youths into the cave and appears to keep watch. In Islam, these youths are referred to as the People of the Cave.

Christian interpretation

Story

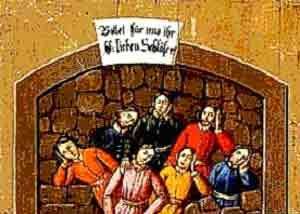

The story says that during the persecutions by the Roman emperor Decius, around 250 AD, seven young men were accused of following Christianity. They were given some time to recant their faith, but chose instead to give their worldly goods to the poor and retire to a mountain cave to pray, where they fell asleep. The emperor, seeing that their attitude towards paganism had not improved, ordered the mouth of the cave to be sealed.[1]

Decius died in 251, and many years passed during which Christianity went from being persecuted to being the state religion of the Roman Empire. At some later time – usually given as during the reign of Theodosius II (408–450) – the landowner decided to open up the sealed mouth of the cave, thinking to use it as a cattle pen. He opened it and found the sleepers inside. They awoke, imagining that they had slept but one day, and sent one of their number to Ephesus to buy food, with instructions to be careful lest the pagans recognize and seize him.

Upon arriving in the city, this person was astounded to find buildings with crosses attached; the townspeople for their part were astounded to find a man trying to spend old coins from the reign of Decius. The bishop was summoned to interview the sleepers; they told him their miracle story, and died praising God.[1] The various lives of the Seven Sleepers in Greek are listed at BHG 1593–1599,[6] and in other non-Latin languages at BHO 1013-1022.[7]

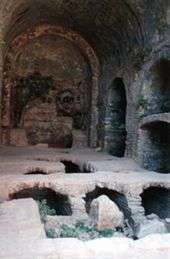

As the earliest versions of the legend spread from Ephesus, an early Christian catacomb came to be associated with it, attracting scores of pilgrims. On the slopes of Mount Pion (Mount Coelian) near Ephesus (near modern Selçuk in Turkey), the grotto of the Seven Sleepers with ruins of the church built over it was excavated in 1927–1928. The excavation brought to light several hundred graves dated to the 5th and 6th centuries. Inscriptions dedicated to the Seven Sleepers were found on the walls of the church and in the graves. This grotto is still shown to tourists.

Syriac origins

The story appeared in several Syriac sources before Gregory's lifetime. It was retold by Symeon the Metaphrast. The Seven Sleepers form the subject of a homily in verse by the Edessan poet-theologian Jacob of Serugh (died 521), which was published in the Acta Sanctorum. Another sixth-century version, in a Syrian manuscript in the British Museum (Cat. Syr. Mss, p. 1090), gives eight sleepers. There are considerable variations as to their names.

Dissemination

The story rapidly attained a wide diffusion throughout Christendom, popularized in the West by Gregory of Tours, in his late 6th-century collection of miracles, De gloria martyrum (Glory of the Martyrs). Gregory says that he had the legend from "a certain Syrian".

In the following century, Paul the Deacon told the tale in his History of the Lombards (i.4) but gave it a different setting: "In the farthest boundaries of Germany toward the west-north-west, on the shore of the ocean itself, a cave is seen under a projecting rock, where for an unknown time seven men repose wrapped in a long sleep." Their dress identified them as Romans, according to Paul, and none of the local barbarians dared to touch them.

During the period of the Crusades, bones from the sepulchres near Ephesus, identified as relics of the Seven Sleepers, were transported to Marseille, France in a large stone coffin, which remained a trophy of the Abbey of Saint Victor, Marseille.

The Seven Sleepers were included in the Golden Legend compilation, the most popular book of the later Middle Ages, which fixed a precise date for their resurrection, 478 AD, in the reign of Theodosius.[8][9]

Early modern literature

The account had become proverbial in 16th century Protestant culture. The poet John Donne could ask,

were we not wean'd till then?

But suck'd on country pleasures, childishly?

Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers' den?

— John Donne, "The good-morrow".

In John Heywood's Play called the Four PP (1530s), the Pardoner, a Renaissance update of Chaucer's Pardoner, offers his companions the opportunity to kiss "a slipper / Of one of the Seven Sleepers," but the relic is presented as absurdly as the Pardoner's other offerings, which include "the great-toe of the Trinity" and "a buttock-bone of Pentecost."[10]

Little is heard of the Seven Sleepers during the Enlightenment, but the account revived with the coming of Romanticism. The Golden Legend may have been the source for retellings of the Seven Sleepers in Thomas de Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, in a poem by Goethe, Washington Irving's "Rip van Winkle", H. G. Wells's The Sleeper Awakes. It also might have an influence on the motif of the "king in the mountain". Mark Twain did a burlesque of the story of the Seven Sleepers in Chapter 13 of Volume 2 of The Innocents Abroad.[11]

Modern literature

Serbian writer Danilo Kiš retells the story of the Seven Sleepers in a short story, "The Legend of the Sleepers", in his book The Encyclopedia of the Dead. Italian author Andrea Camilleri incorporates the story in his novel The Terracotta Dog.

The Seven Sleepers appear in two books of Susan Cooper's The Dark Is Rising series; Will Stanton awakens them in The Grey King, and in Silver on the Tree they ride in the last battle against the Dark.

The Seven Sleepers series by Gilbert Morris takes a modern approach to the story, in which seven teenagers must be awakened to fight evil in a post-nuclear-apocalypse world.

John Buchan refers to the Seven Sleepers in The Three Hostages, where Richard Hannay surmises that his wife Mary, who is a sound sleeper, is descended from one of the seven who has married one of the Foolish Virgins.

The Persian–Dutch writer Kader Abdolah gives his own interpretation of the Islamic version of the story (see below) in the 2000 book Spijkerschrift,[12] based on the writer's experience in the left-wing opposition to both the Shah's regime and the Islamic Republic. The book includes extensive quotations from the Quran's account. At its end the narrator's sister and fellow-activist escapes from prison and, together with other escaped political prisoners, hides in a mountain cave in north Iran, where they will sleep until Iran is free of oppression.

Turkish author Orhan Pamuk alludes to the story, more specifically through the element of the dog, in the chapter "I am a Dog" in his 2001 novel, My Name Is Red.

Islamic interpretation

Qur'an and Islamic scholarly interpretation

The story of the Companions of the Cave is referred to in Surah 18 (verses 9-26).[13] According to Muslim scholars, God revealed these verses because the people of Mecca challenged Muhammad with questions that were passed on to them from the Jews of Medina in an effort to test his authenticity. They asked him about young men who disappeared in the past, about a man who traveled the earth from east to west, Zulqurnain, and about the soul. The story parallels the Christian version, recounting the story of a group of young believers who resisted the pressure from their people and/or king to worship others beside God, and took refuge in a cave, following which they fell asleep for a long time. When they woke up they thought that they had slept for only a day or so, and they sent one of them back to the city to buy food. His use of old silver coins revealed the presence of these youths to the town. Soon after their discovery, the People of the Cave (as the Qur'an calls them) died and the people of their town built a place of worship at the site of their burial (the cave). The Qur'an does not give their exact number. It mentions that some people would say that they were three, others would say five and some would say seven, in addition to one dog, and that they slept for 300 years, plus 9, which could mean 300 solar years or 309 lunar years (300 solar years are equal to 309 lunar years). (Note: A verse after states, "Say: Allah is best aware how long they tarried. His is the Invisible of the heavens and the earth. How clear of sight is He and keen of hearing! They have no protecting friend beside Him, and He maketh none to share in His government. (26)". The number signifies that the exact amount of time they slept is not something fixed. Rather it is saying that could be 300 plus nine or some unfixed amount of time.)

Location of the cave and duration of stay

Muslims firmly believe in the story as it is mentioned in the Qur'an; however the location of the cave is not mentioned. Some allege that it is in Ephesus, Turkey; others cite a place filled with carved sarcophagi from the late Roman and Byzantine periods, called the Cave of Seven Sleepers in the village of Rajib south of Amman, Jordan.[14] Uyghur Muslims even suggest Tuyukhojam, Turpan is the location of the cave, because they believe that place matches the Qur'an's description. The dates of their alleged sleep are also not given in the Qur'an; some allege that they entered the cave at the time of Decius (250 AD) and they woke up at the time of Theodosius I (378–395) or Theodosius II (408–450), but neither of these dates can be reconciled with the Qur'an's account of sleeping 300 or 309 years. Some Islamic scholars, however, assert that the 300 or 309 years mentioned in the Qur'an refers to periods of time alleged by those telling the tale, rather than a definitive statement by God as to how long they were actually there or this difference can be of solar and lunar years.[15]

In Southern Tunisia, a mosque of Chenini is called "the Mosque of the Seven Sleepers" (Masjid al-Ruqood al-Sebaa) where the sleepers are allegedly buried: in the surroundings of the masjid some uncommonly large tombs (about four meters long) are visible. It is a popular belief that during their long sleep they did not stop growing, so when they woke up they had become giants.

Other Tunisian places where the Seven Sleepers' cave is located are Midès, Tozeur, El-Oudiane (al-Udyān) and Talālat. According to the 17th-century traveller Abu Salim al-Ayyashi, the place where they lie is a mountain over the village of Degache (which he calls Daqyūs).[16]

Another place where popular beliefs locate the Seven Sleepers is Azeffoun in the Kabylie of Algeria, where a legend collected by Auguste Mouliéras[17] speaks of seven shepherds who fled into a cave trying to escape the persecution of Decius (Deqyus) and slept forty years there. According to this version, they did not realize that their sleep was so long (but a baker did, since they tried to pay him with an old coin), and decided to get back to sleep. Accordingly, they are reputed to be still sleeping, in a bush difficult to reach, "an hour's walk east of Azeffoun".[18] Their dog, watching over them, can be heard barking by passers-by.

A "mosque of the Seven Sleepers" also exists in the Algerian village of N'Gaous in Aures, but here the legend is somewhat modified, since the tradition speaks of seven people living there in historical times, who mysteriously disappeared and were miraculously found asleep many years later by the pious Sidi Kacem (d. 1623), who consequently ordered that a mosque be built in that place.[19] It should be noted, however, that the mosque itself incorporates some columns of Roman age, with two inscriptions mentioning Trebonianus Gallus, the successor of Decius.[20]

Another interpretation is based on the earlier legend of Joseph of Arimathea having come to Glastonbury and the cave has been identified as the Chalice Well.[21]

Linguistic derivatives

In Welsh, a late riser may be referred to as a saith cysgadur—seven sleeper—as in the 1885 novel Rhys Lewis by Daniel Owen, where the protagonist is referred to as such in chapter 37, p. 294 (Hughes a'i Fab, Caerdydd, 1948). This has the double meaning of one who wakes at seven—well into the working day in a Welsh rural setting.

In the Middle East and specifically in Syria, people say: "نومات أهل فسّو", which can be translated as: "May you sleep like the people of Ephesus".[22]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3

- ↑ Pieter W. van der Horst (February 2011). Pious Long-Sleepers in Greek, Jewish, and Christian Antiquity (pdf). The Thirteenth International Orion Symposium: Tradition, Transmission, and Transformation: From Second Temple Literature through Judaism and Christianity in Late Antiquity. Jerusalem, Israel. pp. 14–5.

- ↑ Liuzza, R. M. (2016). "The Future is a Foreign Country: The Legend of the Seven Sleepers and the Anglo–Saxon Sense of the Past". In Kears, Carl; Paz, James. Medieval Science Fiction. King's College London, Centre for Late Antique & Medieval Studies. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-9539838-8-9.

- ↑ Martyrologium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2001 ISBN 88-209-7210-7)

- ↑ Stokes, Whitley (1905). The Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee: Félire Óengusso Céli Dé. Harrison and Sons. p. 4.

- ↑ https://archive.org/stream/bibliothecahagi00boll#page/224

- ↑ https://archive.org/stream/bibliothecahagio00peetuoft#page/222/mode/2up

- ↑ "The Seven Sleepers". The Golden Legend. Archived from the original on 6 January 2003.

It is in doubt of that which is said that they slept three hundred and sixty-two years, for they were raised the year of our Lord four hundred and seventy-eight, and Decius reigned but one year and three months, and that was in the year of our Lord two hundred and seventy, and so they slept but two hundred and eight years.

- ↑ Jacobus (1899). "XV — The Seven Sleepers". In Madge, H.D. Leaves from the Golden Legend. C.M. Watts (illustrator). pp. 174–175 – via Google Books.

It is doubt of that which is said that they slept ccclxii. years. For they were raised the year of Our Lord IIIICLXXXIII. And Decius reigned but one year and three months and that was in the year of our Lord CC and LXX., and so they slept but iic. and viii. years.

- ↑ Gassner, John, ed. (1987). Medieval and Tudor Drama. New York: Applause. p. 245. ISBN 9780936839844.

- ↑ Samuel Clements (1976). Lawrence Teacher, ed. The Unabridged Mark Twain. Philadelphia PA: Running Press. pp. 245–248.

- ↑ Abdolah, Kader (2006) [2000]. Spijkerschrift [My Father's Notebook].

- ↑ http://submission.ws/sura-18-the-cave-al-kahf/ The Cave- Sura 18 – Quran – English Version

- ↑ http://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/destinations/middle-east/jordan/amman-top-ten-things-to-do-activities/

- ↑ "Surah 18. Al-Kahf". Quran in English. (18:25). Archived from the original on 5 May 2007.

They remained in the Cave for three hundred years; and some others add nine more years.

- ↑ Virginie Prevost, L'aventure ibāḍite dans le Sud tunisien (VIIIe-XIIIe siècle): effervescence d'une région méconnue, Helsinki, Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2008, ISBN 9789514110191, p. 316.

- ↑ "Wid yeṭṭsen i sebɛa di lɣar g Uẓeffun": Auguste Mouliéras, Légendes et contes merveilleux de la Grande Kabylie, Paris 1893–1895, tome I, p. 327-330.

- ↑ Amadaɣ-enni yebɛed af Uẓeffun tikli n esseɛa, i ǧǧiha n eccerq.

- ↑ Laurent-Charles Féraud, "Entre Setif et Biskara" Revue Africaine 21 (1860) p. 187-200. The legend is told at p. 193.

- ↑ The inscriptions are reproduced by Féraud (1860), p. 191 and 192.

- ↑ Hadhrat al-Hajj Mirza Bashirudeen Mahmood Ahmad - Khalifatul Masih II. 'The Holy Quran' with English Translation & Commentary (5 volumes), see also Noorudin, Hadhrat al-Hajj Hafiz Hakim Maulana. Haqaiqul Furqan iii.

- ↑ Sourianet.net Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Seven Sleepers. |

- Quran – Authorized English Version The Cave- Sura 18 – Quran – Authorized English Version

- "SS. Maximian, Malchus, Martinian, Dionysius, John, Serapion, and Constantine, Martyrs", Butler's Lives of the Saints

- Seven Sleepers videos

- (in English) Text containing the Seven Sleepers' commemoration as part of the Office of Prime.

- Sura al-Kahf at Wikisource

- (in English) Photos of the excavated site of the Seven Sleepers cult.

- (in English) The Grotto of the Seven Sleepers, Ephesus

- (in English) Mardan-e-Anjelos is a historical reenactment of the story of Ashaab-e-Kahf (also known as "The Companions of the Cave")

- Link to 3D stereoview image for cross-eyed free viewing technique of Seven Sleepers near Ephesus – Turkey

- Gregory of Tours, The Patient Impassioned Suffering of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus translated by Michael Valerie

- The Lives of the Seven Sleepers from The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Varagine, William Caxton Middle English translation.

- The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus by Chardri, translated into English by Tony Devaney Morinelli: Medieval Sourcebook. fordham.edu

.jpg)

_(14766060212).jpg)