Generations of Noah

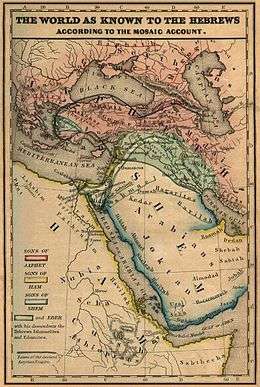

The Generations of Noah or Table of Nations (Genesis 10 of the Hebrew Bible) is a genealogy of the sons of Noah and their dispersion into many lands after the Flood,[1] focusing on the major known societies. The term nations to describe the descendants is a standard English translation of the Hebrew word "goy", following the c. 400 CE Latin Vulgate's "nationes", and does not have the same political connotations that the word entails today.[2]

The list of 70 names introduces for the first time a number of well known ethnonyms and toponyms important to biblical geography[3] such as Noah's three sons Shem, Ham and Japheth, from which were derived Semites, Hamites and Japhetites, certain of Noah's grandsons including Elam, Ashur, Aram, Cush, and Canaan, from which the Elamites, Assyrians, Arameans, Cushites and Canaanites, as well as further descendants including Eber (from which "Hebrews"), the hunter-king Nimrod, the Philistines and the sons of Canaan including Heth, Jebus and Amorus, from which Hittites, Jebusites and Amorites.

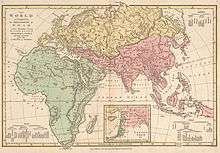

As Christianity took over the Roman world, it adopted the idea that all the world's peoples were descended from Noah. But the tradition of Hellenistic Jewish identifications of the ancestry of various peoples, which concentrates very much on the East Mediterranean and the Near East and is described below, became stretched and its historicity questioned. Not all Near Eastern people were covered, and northern peoples important to the Late Roman and medieval world, such as the Celtic, Slavic, Germanic and Nordic peoples were not covered, nor were others of the world's peoples, such as sub-Saharan Africans, Native Americans and peoples of Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Far East and Australasia. A variety of arrangements were devised by scholars in order to make the table fit, with for example the Scythians, who do feature in the tradition, being claimed as the ancestors of much of northern Europe.[4]

According to Joseph Blenkinsopp, the 70 names in the list express symbolically the unity of the human race, corresponding to the 70 descendants of Israel who go down into Egypt with Jacob at Genesis 46:27 and the 70 elders of Israel who visit God with Moses at the covenant ceremony in Exodus 24:1–9.[5]

Table of Nations

Book of Genesis

.jpg)

Chapters 1–11 of the Book of Genesis are structured around five toledot statements ("these are the generations of..."), of which the "generations of the sons of Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth" is the fourth. Events before the Genesis flood narrative, the central toledot, correspond to those after: the post-Flood world is a new creation corresponding to the Genesis creation narrative, and like Adam, Noah has three sons who will populate the world. The correspondences extend forward as well: there are 70 names in the Table, corresponding to the 70 Israelites who go down into Egypt at the end of Genesis and to the 70 elders of Israel who go up the mountain with Sinai to meet with God in Exodus. The symbolic force of these numbers is underscored by the way the names are frequently arranged in groups of seven, suggesting that the Table is a symbolic means of implying universal moral obligation.[6] The number 70 also goes back to the predecessor of Hebrew religion, the Canaanite mythology, where 70 represents the amount of gods in the divine clan who are each assigned a subject people, and where the supreme god El and his consort, Asherah, has the title "Mother/Father of 70 gods," which, due to the coming of monotheism, had to be changed, but its symbolism lived on in the new religion.

The overall structure of the Table is:

- 1. Introductory formula, v.1

- 2. Japheth, vv.2–5

- 3. Ham, vv.6–20

- 4. Shem, 21–31

- 5. Concluding formula, v.32.[7]

The overall principle governing the assignment of various peoples within the Table is difficult to discern: it purports to describe all humankind, but in reality restricts itself to the Egyptian lands of the south, the Mesopotamian lands, and Anatolia/Asia Minor and the Ionian Greeks, and in addition, the "sons of Noah" are not organised by geography, language family or ethnic groups within these regions.[8] The Table contains several difficulties: for example, the names Sheba and Havilah are listed twice, first as descendants of Cush the son of Ham (verse 7), and then as sons of Joktan, the great-grandsons of Shem, and while the Cushites are North African in verses 6–7 they are unrelated Mesopotamians in verses 10–14.[9]

The date of composition of Genesis 1–11 cannot be fixed with any precision, although it seems likely that an early brief nucleus was later expanded with extra data.[10] Portions of the Table itself 'may' derive from the 10th century BCE, while others reflect the 7th century BCE and priestly revisions in the 5th century BCE.[1] Its combination of world review, myth and genealogy corresponds to the work of the Greek historian Hecataeus of Miletus, active c.520 BCE.[11]

Book of Chronicles

I Chronicles 1 includes a version of the Table of Nations from Genesis, but edited to make clearer that the intention is to establish the background for Israel. This is done by condensing various branches to focus on the story of Abraham and his offspring. Most notably, it omits Genesis 10:9–14, in which Nimrod, a son of Cush, is linked to various cities in Mesopotamia, thus removing from Cush any Mesopotamian connection. In addition, Nimrod does not appear in any of the numerous Mesopotamian King Lists.[12]

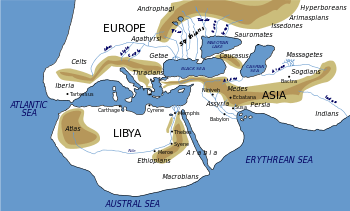

Book of Jubilees

The Table of Nations is expanded upon in detail in chapters 8–9 of the Book of Jubilees, sometimes known as the "Lesser Genesis," a work from the early Second Temple period.[13] Jubilees is considered pseudepigraphical by most Christian and Jewish sects but thought to have been held in regard by many of the Church Fathers.[14] Its division of the descendants throughout the world are thought to have been heavily influenced by the "Ionian world map" described in the Histories (Herodotus),[15] and the anomalous treatment of Canaan and Madai are thought to have been "propaganda for the territorial expansion of the Hasmonean state".[16]

Septuagint version

The Hebrew bible was translated into Greek in Alexandria at the request of Ptolemy II, who reigned over Egypt 285–246 BCE.[17] Its version of the Table of Nations is substantially the same as that in the Hebrew text, but with the following differences:

- It lists Elisa as an extra son of Japheth, giving him eight instead of seven, while continuing to list him also as a son of Javan, as in the Masoretic text.

- Whereas the Hebrew text lists Shelah as the son of Arpachshad in the line of Shem, the Septuagint has a Cainan as the son of Arpachshad and father of Shelah – the Book of Jubilees gives considerable scope to this figure. Cainan appears again at the end of the list of the sons of Shem.

- Obal, Joktan's eighth son in the Masoretic text, does not appear.[18]

1 Peter

In the First Epistle of Peter, 3:20, Saint Peter noted that eight righteous persons were saved from the Great Flood, referring to Noah's family members.

Sons of Noah: Shem, Ham and Japheth

The Genesis flood narrative tells how Noah and his three sons Shem, Ham, and Japheth, together with their wives, were saved from the Deluge to repopulate the Earth.

- Shem is the oldest son according to the Book of Genesis chapter 10 verse 21. Genesis chapter 10 verse 21 Shem was the ancestor of all the Hebrew. Shem was the ancestor of Abraham and thus the Israelites.[19] In the view of some 17th-century European scholars (e.g., John Webb), the people of American, eastern Persia and "the Indias" descended from Shem.[20]

- Ham is Noah’s middle son. The forefather of Cush, Egypt, and Put, and of Canaan, whose lands include portions of Africa, Arabia, Syria-Palestine and Mesopotamia. The etymology of his name is uncertain; some scholars have linked it to terms connected with divinity, but a divine or semi-divine status for Ham is unlikely.[21]

- Japheth is the youngest son. His name is associated with the mythological Greek Titan Iapetos, and his sons include Javan, the Greek-speaking cities of Ionia.[22] In Genesis 9:27 it forms a pun with the Hebrew root yph: "May God make room [the hiphil of the yph root] for Japheth, that he may live in Shem's tents and Canaan may be his slave."[23]

Ethnological interpretations

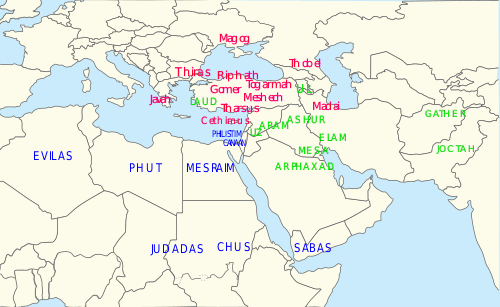

In Flavius Josephus

The 1st-century Jewish-Roman historian Josephus, in Antiquities of the Jews Book 1, chapter 6, was among the first of many who attempted to assign known ethnicities to some of the names listed in Genesis chapter 10. His assignments became the basis for most later authors, and were as follows:[24]

- Gomer: "those whom the Greeks now call Galatians, [Galls,] but were then called Gomerites".

- Aschanax (Ashkenaz): "Aschanaxians, who are now called by the Greeks Rheginians".

- Riphath: "Ripheans, now called Paphlagonians".

- Thrugramma (Togarmah): "Thrugrammeans, who, as the Greeks resolved, were named Phrygians".

- Magog: "Magogites, but who are by the Greeks called Scythians".

- Madai: "the Madeans, who are called Medes, by the Greeks".

- Javan: "Ionia, and all the Grecians".

- Elisa: "Eliseans... they are now the Aeolians".

- Tharsus (Tarshish): "Tharsians, for so was Cilicia of old called". He also derives the name of their city Tarsus from Tharsus.

- Cethimus (Kittim): "The island Cethima: it is now called Cyprus". He also derives the Greek name of their city, which he spells Citius, from Cethimus.

- Thobel (Tubal): "Thobelites, who are now called Iberes".

- Mosoch (Meshech): "Mosocheni... now they are Cappadocians." He also derives the name of their capital Mazaca from Mosoch.

- Thiras (Tiras): "Thirasians; but the Greeks changed the name into Thracians".

- Chus (Cush): "Ethiopians... even at this day, both by themselves and by all men in Asia, called Chusites".

- Sabas (Seba): Sabeans

- Evilas (Havilah): "Evileans, who are called Getuli".

- Sabathes (Sabta): "Sabathens, they are now called by the Greeks Astaborans".

- Sabactas (Sabteca): Sabactens

- Ragmus (Raamah): Ragmeans

- Judadas (Dedan): "Judadeans, a nation of the western Ethiopians".

- Sabas (Sheba): Sabeans

- Mesraim (Misraim): Egypt, which he says is called Mestre in his country.

- "Now all the children of Mesraim, being eight in number, possessed the country from Gaza to Egypt, though it retained the name of one only, the Philistim; for the Greeks call part of that country Palestine. As for the rest, Ludieim, and Enemim, and Labim, who alone inhabited in Libya, and called the country from himself, Nedim, and Phethrosim, and Chesloim, and Cephthorim, we know nothing of them besides their names; for the Ethiopic war which we shall describe hereafter, was the cause that those cities were overthrown."

- Phut: Libya. He states that a river and region "in the country of Moors" was still called Phut by the Greeks, but that it had been renamed "from one of the sons of Mesraim, who was called Lybyos".

- Canaan: Judea, which he called "from his own name Canaan".

- Sidonius (Sidon): The city of Sidonius, "called by the Greeks Sidon".

- Amathus (Hamathite): "Amathine, which is even now called Amathe by the inhabitants, although the Macedonians named it Epiphania, from one of his posterity."

- Arudeus (Arvadite): "the island Aradus".

- Arucas (Arkite): "Arce, which is in Libanus".

- "But for the seven others [sons of Canaan], Chetteus, Jebuseus, Amorreus, Gergesus, Eudeus, Sineus, Samareus, we have nothing in the sacred books but their names, for the Hebrews overthrew their cities".

- Elam: "Elamites, the ancestors of the Persians".

- Ashur: "Assyrians, and their city Niniveh built by Ashur.

- Arphaxad: "Arphaxadites, who are now called Chaldeans".

- Sala

- Heber (Eber): "from whom they originally called the Jews Hebrews".

- Phaleg (Peleg): He notes that he was so named "because he was born at the dispersion of the nations to their several countries; for Phaleg among the Hebrews signifies division".

- Joctan

- "Elmodad, Saleph, Asermoth, Jera, Adoram, Aizel, Decla, Ebal, Abimael, Sabeus, Ophir, Euilat, and Jobab. These inhabited from Cophen, an Indian river, and in part of Asia adjoining to it."

- Heber (Eber): "from whom they originally called the Jews Hebrews".

- Sala

- Aram: "Aramites, which the Greeks called Syrians".

- Uz: "Uz founded Trachonitis and Damascus: this country lies between Palestine and Celesyria".

- Ul (Hul): Armenia

- Gather (Gether): Bactrians

- Mesa (Mesh): "Mesaneans; it is now called Charax Spasinu".

- Laud (Lud): "Laudites, which are now called Lydians".

In Hippolytus

Hippolytus of Rome, in his Diamerismos (c. 234, existing in numerous Latin and Greek copies),[25] made another attempt to assign ethnicities to the names in Genesis 10. It is thought to have been based on the Book of Jubilees.[26]

Its differences versus that of Josephus are shown below:

- Gomer – Cappadocians

- Ashkenaz – Sarmatians

- Riphath – Sauromatians

- Togarmah – Armenians

- Magog – Galatians, Celts

- Javan

- Elishah – Sicels (Chron Pasc: Trojans and Phrygians)

- Tarshish – Iberians, Tyrrhenians

- Kittim – Macedonians, Romans, Latins

- Tubal – "Hettali" (?)

- Meshech – Illyrians

- Misraim

- Ludim – Lydians

- Anamim – Pamphylians

- Pathrusim – Lycians (var.: Cretans)

- Caphtorim – Cilicians

- Put – Troglodytes

- Canaan – Afri and Phoenicians

- Arkite – Tripolitanians

- Lud – Halizones

- Arpachshad

- Cainan – "those east of the Sarmatians" (one variant)

- Joktan

- Elmodad – Indians

- Saleph – Bactrians

- Hazamaveth, Sheba – Arabs

- Adoram – Carmanians

- Uzal – Arians (var.: Parthians)

- Abimael – Hyrcanians

- Obal – Scythians

- Ophir – Armenians

- Deklah – Gedrosians

- Joktan

- Cainan – "those east of the Sarmatians" (one variant)

- Aram – "Etes" ?

- Hul – Lydians (var: Colchians)

- Gether – "Gaspeni" ?

- Mash – Mossynoeci (var: Mosocheni)

The Chronography of 354, the Panarion by Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 375), the Chronicon Paschale (c. 627), the History of Albania by the Georgian historian Movses Kaghankatvatsi (7th century), and the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes (c. 1057) follow the identifications of Hippolytus.

In Jerome

Jerome, writing c. 390, provided an 'updated' version of Josephus' identifications in his Hebrew Questions on Genesis. His list is substantially identical to that of Josephus in almost all respects, but with the following notable differences:

In Isidore of Seville and later authors

The scholar Isidore of Seville, in his Etymologiae (c. 600), repeats all of Jerome's identifications, but with these minor changes:[27]

- Joktan, son of Eber: Indians

- Saleph, son of Joktan: Bactrians

- Magog, son of Japheth: "Scythians and Goths"

- Ashkenaz, son of Gomer: "Sarmatians, whom the Greeks call Rheginians".

Isidore's identifications for Japheth's sons were repeated in the Historia Brittonum attributed to Nennius. Isidore's identifications also became the basis for numerous later mediaeval scholars, remaining so until the Age of Discovery prompted newer theories, such as that of Benito Arias Montano (1571), who proposed connecting Meshech with Moscow, and Ophir with Peru.

While Genesis 10 was covered extensively by numerous Christian, Jewish and Muslim scholars over many centuries, the phrase "Table" of nations only appeared and became popular in English from the 1830s.

In the early 6th century CE, perhaps in Byzantine Constantinople (or elsewhere in the Eastern Roman Empire), the commonly-termed "Frankish Table of Nations" was created, likely under the influence of Gothic sources. It drew heavily from Tacitus's Germania and is notable for its focus on linking the various Germanic peoples (and their neighbors) of the 6th century to Trojan and Biblical ancestors. The text was eventually transmitted to Frankish Gaul by the 6th to 7th centuries and in the early 9th century CE, likely due to its reference to the ancestry of the Britons, was used as a primary source by an anonymous Welsh scribe for the Historia Brittonum.[28][29]

Other interpretations: Descendants of Japheth

%2C_Isidore-Codex_236.png)

The Greek Septuagint (LXX) text of Genesis includes an additional son of Japheth, "Elisa", between Javan and Tubal; however, as this name is found in no other ancient source, nor in I Chronicles, he is almost universally agreed to be a duplicate of Elisha, son of Javan. The presence of Elisa and of Cainan son of Arpachshad (below) in the Greek Bible accounts for the traditional enumeration among early Christian sources of 72 names, as opposed to the 70 names found in Jewish sources and Western Christian sources.

- Gomer: the Cimmerians, a people from the northern Black Sea, made incursions into Anatolia in the eighth and early seventh centuries BCE before being confined to Cappadocia.[30]

- Ashkenaz: A people of the Black and Caspian sea areas, much later associated with German and East European Jews.[31] The Ashkuza, who lived on the upper Euphrates in Armenia expelled the Cimmerians from their territory, and in Jeremiah 51:27 were said to march against Babylon along with two other northern kingdoms.[32]

- Riphath (Diphath in Chronicles): Josephus identification Riphath with the Paphlagonians of later antiquity, but this appears to have been no more than a guess; the Book of Jubilees identifies the name with the "Riphean Mountains", equated with the Causcasus in Classical sources, and the general understanding seems to have been invaders from the Causcuses who were settled in Armenia or Cappadocia.[33]

- Togarmah: Associated with Anatolia in Ezekiel.[31] Later Armenian historians claimed Togarmah as an ancestor.[33]

- Magog: Associated in Ezekiel with Gog, a king of Lydia, and thereby with Anatolia.[31] The first century CE Jewish historian Josephus stated that Magog was identical with the Scythians, but modern scholars are sceptical of this and place Magog simply somewhere in Anatolia.[34]

- Madai: The Medes, from an area now in northwest Iran.[31]

- Javan: This name is universally agreed to refer to the Ionians (Greeks) of the western and southern coast of Anatolia.[35]

- Elishah: Possibly Elaioussa, an island off the coast of Cilicia, or an old name for the island of Cyprus.[35]

- Tarshish (Tarshishah in Chronicles): Candidates include (Tartessos) in Spain and Tharros in Sardinia, both of which appear unlikely, and Tarsus in Cilicia, which appears more likely despite some linguistic difficulties.[36]

- Kittim: Originally the inhabitants of Kition in Cyprus, later the entire island; in the Dead Sea Scrolls the Kittim appear to be the Romans.[31]

- Dodanim (Rodanim in Chronicles): Inhabitants of Rhodes.[31]

- Tubal: Tubal and Meshech always appear as a pair in the Old Testament.[37] The name Tubal is connected with Tabal and Greek Tipaprivoi, a people of Cappadocia, in the north-east of Anatolia.[38]

- Meshech: Mushki/Muski had its capital at Gordium and fused with the kingdom of Phrygia by the 8th century.[39]

- Tiras: Josephus and late Rabbinical writers associated Tiras with Thrace, the part of Europe opposite Anatolia, but all the other sons of Japheth are located in Anatolia itself and it is possible that Tiras may refer to Thracians inhabiting westernmost Anatolia; it has also been associated with some of the Sea Peoples such as Tursha and Tyrrhenians, but this is considered unlikely.[40]

Other interpretations: Descendants of Ham

- Cush: The biblical transliteration of the Egyptian name for Nubia or Ethiopia; the "sons of Cush" which follow are various locations on the Arabian and possibly African coasts bordering the Red Sea.[41]

- Seba (son of Cush). Has been connected with both Yemen and Ethiopia, with much confusion with Sheba below.

- Havilah, son of Cush

- Sabtah (son of Cush)

- Raamah (son of Cush).

- Sabtechah, son of Cush

- Nimrod: Possibly connected with Naram-Sin, a 3rd millennium king of Akkad;in verses 10–12 he is the founder of a list of Mesopotamian cities, and the biblical tradition elsewhere identifies him with northern Mesopotamia or Assyria.[42] His location (Mesopotamia) is something of an anomaly, in that the other sons of Cush are connected with Africa or the Red Sea, and he is probably a late insertion resulting from a confusion between the African Cush and a quite different Cush, the eponym (ancestor) of the Kassites.[43]

- Mizraim: Egypt.[44]

- Ludim, offspring of Mizraim.

- Anamim, offspring of Mizraim.

- Lehabim, offspring of Mizraim.

- Naphtuhim, offspring of Mizraim.

- Pathrusim, offspring of Mizraim.

- Casluhim ("out of whom came Philistim" – Genesis 10:14, 1Chronicles 1:12)

- Caphtorim: Probably the island of Crete. According to Deuteronomy 2:23, Caphtorim settled in Gaza, an important Philistinian city.[42]

- Phut: the Septuagint translates this as Libyans, which would be in accordance with the north–to–south progression in the listing of Ham's descendants, but some scholars have suggested Punt, the Egyptian name for Somalia.[45]

- Canaan: The strip of land west of the Jordan River including modern Lebanon and parts of Syria, and the varied peoples who lived there.[46]

- Sidon: The main Phoenician city, often treated as synonymous with Phoenicia.[47]

- Heth: Probably the ancestor of the biblical Hittites, although the Hittites of Anatolia had no ethnic or linguistic ties with the peoples of Canaan.[48]

- "the Jebusite", offspring of Canaan.

- "the Amorite": Generic name for West Semitic peoples of the Fertile Crescent.[48]

- "the Girgasites", offspring of Canaan

- "the Hivite", offspring of Canaan

- "the Arkite", offspring of Canaan.

- "the Sinite", offspring of Canaan.

- "the Arvadite", offspring of Canaan.

- "the Zemarite", offspring of Canaan.

- "the Hamathite", offspring of Canaan.

Beginning in the 9th century with the Jewish grammarian Judah ibn Quraysh, a relationship between the Semitic and Cushitic languages was seen; modern linguists group these two families, along with the Egyptian, Berber, Chadic, and Omotic language groups into the larger Afro-Asiatic language family. In addition, languages in the southern half of Africa are now seen as belonging to several distinct families independent of the Afro-Asiatic group. Some now discarded Hamitic theories have become viewed as racist; in particular a theory proposed in the 19th century by Speke, that the Tutsi were supposedly of some Hamitic ancestry and thus inherently superior.[49]

The 17th-century Jesuit, Athanasius Kircher, thought that the Chinese had also descended from Ham, via Egyptians.

Other interpretations: Descendants of Shem

- Elam: A kingdom east of Assyria and Babylonia and along the Persian Gulf.[50] The Elamites called their land Haltamti and had an empire (capital Susa) in what is now Khuzistan, modern Iran. Elamite is not a Semitic language, but a Language Isolate.

- Ashur: Assyria, which was not West Semitic like the Hebrews, but an East Semitic speaking kingdom in Upper Mesopotamia. In the much older Assyrian tradition itself, Ashur is the name of the chief deity in Mesopotamian religion and the name of the city state of Assur.[50]

- Arpachshad: An obscure name of uncertain meaning, although apparently associated with Assyria.[51]

- Cainan is listed as the son of Arpachshad and father of Shelah in the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew bible (the Masoretic text) made in the last few centuries before the modern era. The name is omitted in the Hebrew bible. The genealogy of Jesus in St. Luke 3:36, which is taken from the Septuagint rather than the Hebrew text, include the name.

- Salah (also transcribed Shelah) son of Arpachshad (or Cainan).

- Eber son of Shelah: The ancestor of Abraham and the Hebrews, he has a significant place as the 14th from Adam.[52]

- Peleg: The name means "division," and may refer to the division of the peoples in the Tower of Babel incident which follows, or to Peleg and his descendants being "divided out" as the chosen people of God.[53]

- Joktan: The name is Arabic, and his 13 "sons," so far as they can be identified, correspond to the west and southwest of the Arabian peninsula.[54]

- Lud: The kingdom of Lydia in eastern Anatolia.[50] However, Lydia was Indo-Anatolian speaking and not West Semitic and not geographically near the other "sons of Shem", which makes its presence in the list difficult to explain.[51]

- Aram: Mesopotamia and Syria.[50]

- Uz, son of Aram.

- Hul, son of Aram.

- Gether, son of Aram.

- Mash, son of Aram (1 Chronicles has Meshech).

Extrabiblical sons of Noah

There exist various traditions in post-biblical and talmudic sources claiming that Noah had children other than Shem, Ham, and Japheth who were born before the Deluge.

According to the Quran (Hud 42–43), Noah had another unnamed son who refused to come aboard the Ark, instead preferring to climb a mountain, where he drowned. Some later Islamic commentators give his name as either Yam or Kan'an.[55]

According to Irish mythology, as found in the Annals of the Four Masters and elsewhere, Noah had another son named Bith who was not allowed aboard the Ark, and who attempted to colonise Ireland with 54 persons, only to be wiped out in the Deluge.

Some 9th-century manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle assert that Sceafa was the fourth son of Noah, born aboard the Ark, from whom the House of Wessex traced their ancestry; in William of Malmesbury's version of this genealogy (c. 1120), Sceaf is instead made a descendant of Strephius, the fourth son born aboard the Ark (Gesta Regnum Anglorum).

An early Arabic work known as Kitab al-Magall "Book of Rolls" (part of Clementine literature) mentions Bouniter, the fourth son of Noah, born after the flood, who allegedly invented astronomy and instructed Nimrod.[56] Variants of this story with often similar names for Noah's fourth son are also found in the c. fifth century Ge'ez work Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan (Barvin), the c. sixth century Syriac book Cave of Treasures (Yonton), the seventh century Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius (Ionitus[57]), the Syriac Book of the Bee 1221 (Yônatôn), the Hebrew Chronicles of Jerahmeel, c. 12th–14th century (Jonithes), and throughout Armenian apocryphal literature, where he is usually referred to as Maniton; as well as in works by Petrus Comestor c. 1160 (Jonithus), Godfrey of Viterbo 1185 (Ihonitus), Michael the Syrian 1196 (Maniton), Abu al-Makarim c. 1208 (Abu Naiţur); Jacob van Maerlant c. 1270 (Jonitus), and Abraham Zacuto 1504 (Yoniko).

Martin of Opava (c. 1250), later versions of the Mirabilia Urbis Romae, and the Chronicon Bohemorum of Giovanni di Marignola (1355) make Janus (the Roman deity) the fourth son of Noah, who moved to Italy, invented astrology, and instructed Nimrod.

According to the monk Annio da Viterbo (1498), the Hellenistic Babylonian writer Berossus had mentioned 30 children born to Noah after the Deluge, including sons named Tuisto, Prometheus, Iapetus, Macrus, "16 titans", Cranus, Granaus, Oceanus, and Tipheus. Also mentioned are daughters of Noah named Araxa "the Great", Regina, Pandora, Crana, and Thetis. However, Annio's manuscript is widely regarded today as having been a forgery.[58]

See also

Notes

- Dillmann, A., Genesis: Critically and Exegetically Expounded, Vol. 1, Edinburgh, UK, T. and T. Clark, 1897, 314.

- Kautzsch, E.F.: quoted by James Orr, "The Early Narratives of Genesis," in The Fundamentals, Vol. 1, Los Angeles, CA, Biola Press, 1917.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Rogers 2000, p. 1271.

- ↑ Guido Zernatto and Alfonso G. Mistretta (July 1944). "Nation: The History of a Word". The Review of Politics. Cambridge University Press. 6 (3): 351–366. doi:10.1017/s0034670500021331. JSTOR 1404386.

- ↑ "Biblical Geography," Catholic Encyclopedia: "The ethnographical list in Genesis 10 is a valuable contribution to the knowledge of the old general geography of the East, and its importance can scarcely be overestimated."

- ↑ Johnson, James William, "The Scythian: His Rise and Fall", Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Apr., 1959), pp. 250-257, University of Pennsylvania Press, JSTOR

- ↑ Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 156.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp 2011, pp. 4 and 155–156.

- ↑ Towner 2001, p. 102.

- ↑ Gmirkin 2006, p. 140–141.

- ↑ Towner 2001, p. 101–102.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 156–157.

- ↑ Brodie 2001, p. 186.

- ↑ Sadler 2009, p. 123.

- ↑ Scott 2005, p. 4.

- ↑ Machiela 2009.

- ↑ Ruiten 2000.

- ↑ Alexander 1988, p. 102–103.

- ↑ Pietersma & Wright 2007, p. xiii.

- ↑ Scott 2005, p. 25.

- ↑ Strawn 2000a, p. 1205.

- ↑ Mungello, David E. (1989). Curious land: Jesuit accommodation and the origins of Sinology. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 179, 336–337. ISBN 0-8248-1219-0.

there are more references in that book on the early Jesuits' and others' opinions on Noah's Connection to China

- ↑ Strawn 2000b, p. 543.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 158.

- ↑ Thompson 2014, p. 102.

- ↑ "Antiquities of the Jews – Book I".

- ↑ Bauer, Adolf (27 February 2018). "Die Chronik des Hippolytos im Matritensis graecus 121". J.C. Hinrichs – via Google Books.

- ↑ Ådna, Jostein; Kvalbein, Hans (27 February 2018). "The Mission of the Early Church to Jews and Gentiles". Mohr Siebeck – via Google Books.

- ↑ Isidorus (Hispalensis) (2006). Stephen A. Barney, ed. Etymologiae (English translation). Cambridge University Press. pp. 192–193. ISBN 9781139456166. page 192 page 193

- ↑ Goffart, Walter, "The Supposedly 'Frankish' Table of Nations: An Edition and Study, Frühmittelalterliche Studies 17, 1983, pp. 98–130.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards, T. M., Wales and the Britons, 350-1064, Oxford, 2013, p. 439; 441; 454.

- ↑ Gmirkin 2006, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Towner 2001, p. 103.

- ↑ Bøe 2001, p. 48.

- 1 2 Gmirkin 2006, p. 149.

- ↑ Bøe 2001, p. 47–48.

- 1 2 Gmirkin 2006, p. 150.

- ↑ Gmirkin 2006, p. 150–152.

- ↑ Bøe 2001, p. 101.

- ↑ Bøe 2001, p. 102.

- ↑ Gmirkin 2006, p. 148.

- ↑ Gmirkin 2006, p. 149–150.

- ↑ Gmirkin 2006, p. 161.

- 1 2 Towner 2001, p. 104.

- ↑ Uehlinger 1999, p. 628.

- ↑ Matthews 1996, p. 452.

- ↑ Mathews 1996, p. 445.

- ↑ Mathews 1996, p. 445–446.

- ↑ Towner 2001, p. 104–105.

- 1 2 Towner 2001, p. 105.

- ↑ David Moshman (2005). "Theories of Self and Theories as Selves". In Cynthia Lightfoot, Michael Chandler and Chris Lalonde. Changing Conceptions of Psychological Life. Psychology Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0805843361.

- 1 2 3 4 Gmirkin 2006, p. 141.

- 1 2 Gmirkin 2006, p. 142.

- ↑ Matthews 1996, p. 497.

- ↑ Matthews 1996, p. 38.

- ↑ Tooman 2011, p. 160.

- ↑ This was observed as early as 1734, in George Sale's Commentary on the Quran.

- ↑ Klijn, Albertus (1977). Seth: In Jewish, Christian and Gnostic Literature. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-05245-3. , page 54

- ↑ S.P. Brock notes that the earliest Greek texts of Pseudo-Methodius read Moneton, while the Syriac versions have Ionţon (Armenian Apocrypha, p. 117)

- ↑ Gascoigne, Mike. "Travels of Noah into Europe". www.annomundi.com.

Bibliography

- Philip Alexander (1988). "Retelling the Old Testament". It is Written: Scripture Citing Scripture : Essays in Honour of Barnabas Lindars, SSF. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521323475.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011). Creation, Un-creation, Re-creation: A Discursive Commentary on Genesis 1–11. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567372871.

- Bøe, Sverre (2001). Gog and Magog: Ezekiel 38–39 as pre-text for Revelation 19, 17–21 and 20, 7–10. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161475207.

- Brodie, Thomas L. (2001). Genesis As Dialogue : A Literary, Historical, and Theological Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198031642.

- Carr, David McLain (1996). Reading the Fractures of Genesis: Historical and Literary Approaches. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664220716.

- Day, John (2014). "Noah's Drunkenness, the Curse of Canaan". In Baer,, David A.; Gordon, Robert P. Leshon Limmudim: Essays on the Language and Literature of the Hebrew Bible in Honour of A.A. Macintosh. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567308238.

- Gmirkin, Russell (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9780567134394.

- Granerød, Gard (2010). Abraham and Melchizedek. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110223453.

- Kaminski, Carol M. (1995). From Noah to Israel: Realization of the Primaeval Blessing After the Flood. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567539465.

- Keiser, Thomas A. (2013). Genesis 1–11: Its Literary Coherence and Theological Message. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781625640925.

- Knoppers, Gary (2003). "Shem, Ham and Japheth". In Graham, Matt Patrick; McKenzie, Steven L.; Knoppers, Gary N. The Chronicler as Theologian: Essays in Honor of Ralph W. Klein. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826466716.

- Daniel A. Machiela (2009). "A Comparative Commentary on the Earths Division". The Dead Sea Genesis Apocryphon: A New Text and Translation With Introduction and Special Treatment of Columns 13–17. BRILL. ISBN 9789004168145.

- Matthews, K.A. (1996). Genesis 1–11:26. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 9781433675515.

- McEntire, Mark (2008). Struggling with God: An Introduction to the Pentateuch. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780881461015.

- Pietersma, Albert; Wright, Benjamin G. (2005). A New English Translation of the Septuagint. Oxford University Press,. ISBN 9780199743971.

- Rogers, Jeffrey S. (2000). "Table of Nations". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Jacques T. A. G. M. Ruiten (2000). Primaeval History Interpreted: The Rewriting of Genesis 1–11 in the Book of Jubilees. BRILL. ISBN 9789004116580.

- Sadler, Rodney Steven, Jr. (2009). Can a Cushite Change His Skin?: An Examination of Race, Ethnicity, and Othering in the Hebrew Bible. A&C Black.

- Sailhamer, John H. (2010). The Meaning of the Pentateuch: Revelation, Composition and Interpretation. InterVarsity Press.

- Scott, James M. (2005). Geography in Early Judaism and Christianity: The Book of Jubilees. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521020688.

- Strawn, Brent A. (2000a). "Shem". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Strawn, Brent A. (2000b). "Ham". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (2014). "Narrative reiteration and comparative literature: problems in defining dependency". In Thompson, Thomas L.; Wajdenbaum, Philippe. The Bible and Hellenism: Greek Influence on Jewish and Early Christian Literature. Routledge. ISBN 9781317544265.

- Towner, Wayne Sibley (2001). Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664252564.

- Uehlinger, Christof (1999). "Nimrod". In Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter. Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible. Brill. ISBN 9780802824912.

- Wajdenbaum, Philippe (2014). Argonauts of the Desert: Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible. Routledge. ISBN 9781317543893.

External links

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Entry for "Genealogy"

- T. Jones, Alonso. "The Empires of the Bible". (First four chapters for a more standard creationist account).