Anti-Russian sentiment

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Academic disciplines |

|

Organs of government |

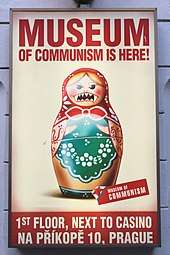

Anti-Russian sentiment (or Russophobia) is a diverse spectrum of negative feelings, dislikes, fears, aversion, derision and/or prejudice of Russia, Russians or Russian culture.[2][3] A wide variety of mass culture clichés about Russia and Russians exists. Many of these stereotypes were originally developed during the Cold War,[4][5] and were primarily used as elements of political war against the Soviet Union. Some of these prejudices are still observed in the discussions of the relations with Russia.[6] Negative representation of Russia and Russians in modern popular culture is also often described as functional, as stereotypes about Russia may be used for framing reality, like creating an image of an enemy, or an excuse, or an explanation for compensatory reasons.[7][8][9][10] Hollywood has been criticised for having Russians as its "go-to villains".[11] Several factors leading to such strong anti-Russian sentiment mostly surrounds historical grievances (including Soviet war crimes), economic competition, imperialist legacies and racism.

On the other hand, Russian nationalists and apologists of the Russian politics are sometimes criticised for using allegations of "Russophobia" as a form of propaganda to counter criticism of Russia.[12][13] The opposite of Russophobia is Russophilia.

Statistics

| Country polled | Favorable | Unfavorable | Neutral | Change from 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

5% | 93% | 2 | ||

15% | 82% | 4 | No Data | |

18% | 78% | 4 | No Data | |

21% | 69% | 10 | ||

27% | 67% | 6 | ||

26% | 64% | 10 | ||

29% | 63% | 9 | ||

32% | 62% | 6 | ||

36% | 62% | 2 | ||

35% | 61% | 3 | ||

27% | 60% | 14 | ||

26% | 59% | 15 | ||

27% | 59% | 14 | ||

37% | 55% | 7 | ||

35% | 54% | 11 | ||

39% | 48% | 13 | No Data | |

47% | 48% | 5 | ||

36% | 41% | 23 | ||

36% | 40% | 24 | ||

28% | 40% | 32 | ||

39% | 37% | 24 | No Data | |

35% | 36% | 29 | ||

38% | 33% | 30 | ||

34% | 31% | 34 | ||

32% | 31% | 37 | No Data | |

64% | 31% | 5 | No Data | |

41% | 31% | 28 | ||

27% | 29% | 44 | ||

45% | 29% | 27 | ||

27% | 27% | 46 | ||

55% | 26% | 19 | ||

32% | 25% | 43 | ||

33% | 24% | 43 | ||

45% | 21% | 34 | ||

34% | 18% | 48 | ||

47% | 13% | 40 | ||

83% | 13% | 5 | ||

88% | 10% | 1 |

In October 2004, the International Gallup Organization announced that according to its poll, anti-Russia sentiment remained fairly strong throughout Europe and the West in general. It found that Russia was the least popular G-8 country globally. The percentage of population with a "very negative" or "fairly negative" perception of Russia was 73% in Kosovo, 62% in Finland, 57% in Norway, 42% in the Czech Republic and Switzerland, 37% in Germany, 32% in Denmark and Poland, and 23% in Estonia. Overall, the percentage of respondents with a positive view of Russia was only 31%.[15][16][17]

According to a 2014 survey by Pew Research Center, attitudes towards Russia in most countries worsened considerably during Russia's involvement in the 2014 crisis in Ukraine. From 2013 to 2014, the median negative attitudes in Europe rose from 54% to 75%, and from 43% to 72% in the United States. Negative attitudes also rose compared to 2013 throughout the Middle East, Latin America, Asia and Africa.[18]

There is the question of whether or not negative attitudes towards Russia and frequent criticism of the Russian government in western media contributes to negative attitudes towards Russian people and culture. In a Guardian article, British academic Piers Robinson claims that "Indeed western governments frequently engage in strategies of manipulation through deception involving exaggeration, omission and misdirection".[19] In a 2012 survey, the percentage of Russian immigrants in the EU that indicated that they had experienced racially motivated hate crimes was 5%, which is less than the average of 10% reported by several groups of immigrants and ethnic minorities in the EU.[20] 17% of Russian immigrants in the EU said that they had been victims of crimes the last 12 months, for example theft, attacks, frightening threats or harassment, as compared to an average of 24% among several groups of immigrants and ethnic minorities.[21]

History

On 19 October 1797 the French Directory received a document from a Polish general, Michał Sokolnicki, entitled "Aperçu sur la Russie". This became known as the so-called "Testament of Peter the Great" and was first published in October 1812, during the Napoleonic wars, in Charles Louis-Lesur's much-read Des progrès de la puissance russe: this was at the behest of Napoleon I, who ordered a series of articles to be published showing that "Europe is inevitably in the process of becoming booty for Russia".[23][24] Subsequent to the Napoleonic wars, propaganda against Russia was continued by Napoleon's former confessor, Dominique Georges-Frédéric de Pradt, who in a series of books portrayed Russia as a "despotic" and "Asiatic" power hungry to conquer Europe.[25] With reference to Russia's new constitutional laws in 1811 the Savoyard philosopher Joseph de Maistre wrote the now famous statement: "Every nation gets the government it deserves" ("Toute nation a le gouvernement qu'elle mérite").[26][27]

In the 1815-1840 period British commentators began complaining about the extreme conservatism of Russia and its efforts to stop or reverse reforms.[28] Fears grew that Russia had plans to cut off communications between Britain and India and was looking to conquer Afghanistan to pursue that goal. This led to the British policies known as the "Great Game" to stop Russian expansion in Central Asia. However, historians with access to the Russian archives have concluded that Russia had no plans involving India, as the Russians repeatedly stated.[29]

In 1867, Fyodor Tyutchev, a Russian poet, diplomat and member of His Imperial Majesty's Own Chancellery, introduced the actual term of "russophobia" in a letter to his daughter Anna Aksakova on 20 September 1867, where he applied it to a number of pro-Western Russian liberals who, pretending that they were merely following their liberal principles, developed a negative attitude towards their own country and always stood on a pro-Western and anti-Russian position, regardless of any changes in the Russian society and having a blind eye on any violations of these principles in the West, "violations in the sphere of justice, morality, and even civilization". He put the emphasis on the irrationality of this sentiment.[30] Tyuchev saw Western anti-Russian sentiment as the result of misunderstanding caused by civilizational differences between East and West.[31] Being an adherent of Pan-Slavism, he believed that the historical mission of Slavic peoples was to be united in a Pan-Slavic and Orthodox Christian Russian Empire to preserve their Slavic identity and avoid cultural assimilation; in his lyrics Poland, a Slavic yet Catholic country, was poetically referred to as Judas among the Slavs.[32] The term returned into political dictionaries of the Soviet Union only in the middle 1930s. Further works by Russian academics, such as Igor Shafarevich's Russophobia[33] or the treaty from the 1980s attributed the spread of russophobia to Zionists.[13]

In 1843 the Marquis de Custine published his hugely successful 1800-page, four volume travelogue La Russie en 1839. Custine's scathing narrative reran what were by now clichés which presented Russia as a place where "the veneer of European civilization was too thin to be credible". Such was its huge success that several official and pirated editions quickly followed, as well as condensed versions and translations in German, Dutch and English. By 1846 approximately 200 thousand copies had been sold.[34]

The influential British economist John Maynard Keynes wrote controversially on Russia, that the oppression in the country, rooted in the Red Revolution, perhaps was "the fruit of some beastliness in the Russian nature", also attributing "cruelty and stupidity" to tyranny in both the "Old Russia" (tsarist) and "New Russia" (Soviet).[35]

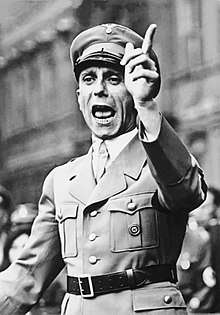

In the 1930s and 1940s, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party viewed the Soviet Union as populated by Slavs ruled by "Jewish Bolshevik" masters.[39]

Hitler stated in Mein Kampf his belief that the Russian state was the work of German elements in the state and not of the Slavs:

Here Fate itself seems desirous of giving us a sign. By handing Russia to Bolshevism, it robbed the Russian nation of that intelligentsia which previously brought about and guaranteed its existence as a state. For the organization of a Russian state formation was not the result of the political abilities of the Slavs in Russia, but only a wonderful example of the state-forming efficacity of the German element in an inferior race.[40]

A secret Nazi plan, the Generalplan Ost called for the enslavement, expulsion or extermination of most Slavic peoples in Europe. Approximately 2.8 million Soviet POWs died of starvation, mistreatment, or executions in just eight months of 1941–42.[41]

"Need, hunger, lack of comfort have been the Russians' lot for centuries. No false compassion, as their stomachs are perfectly extendible. Don't try to impose the German standards and to change their style of life. Their only wish is to be ruled by the Germans. [...] Help yourselves, and may God help you!"

— "12 precepts for the German officer in the East", 1941[42]

On July 13, 1941, three weeks after the invasion of the Soviet Union, Nazi SS leader Heinrich Himmler told the group of Waffen SS men:

This is an ideological battle and a struggle of races. Here in this struggle stands National Socialism: an ideology based on the value of our Germanic, Nordic blood. ... On the other side stands a population of 180 million, a mixture of races, whose very names are unpronounceable, and whose physique is such that one can shoot them down without pity and compassion. These animals, that torture and ill-treat every prisoner from our side, every wounded man that they come across and do not treat them the way decent soldiers would, you will see for yourself. These people have been welded by the Jews into one religion, one ideology, that is called Bolshevism... When you, my men, fight over there in the East, you are carrying on the same struggle, against the same subhumanity, the same inferior races, that at one time appeared under the name of Huns, another time— 1000 years ago at the time of King Henry and Otto I— under the name of Magyars, another time under the name of Tartars, and still another time under the name of Genghis Khan and the Mongols. Today they appear as Russians under the political banner of Bolshevism.[43]

Heinrich Himmler's speech at Posen on October 4, 1943:

What happens to a Russian, to a Czech, does not interest me in the slightest. What the nations can offer in good blood of our type, we will take, if necessary by kidnapping their children and raising them with us. Whether nations live in prosperity or starve to death interests me only in so far as we need them as slaves for our culture; otherwise, it is of no interest to me. Whether 10,000 Russian females fall down from exhaustion while digging an anti-tank ditch interest me only in so far as the anti-tank ditch for Germany is finished. We shall never be rough and heartless when it is not necessary, that is clear. We Germans, who are the only people in the world who have a decent attitude towards animals, will also assume a decent attitude towards these human animals.[44]

Post-Soviet distrust of Russia and Russians is attributable to backlash against the historical memory of Russification pursued by Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union, and backlash against modern policies of the Russian government.[45]

In 2007, Professor of Politics and Political Economy Vlad Sobell believed that "Russophobic sentiment" in the West reflected the West's failure to adapt and change its historical attitude towards Russia, even as Russia had (in his view) abandoned past ideology for pragmatism, successfully driving its economic revival. With the West victorious over totalitarianism, Russia served to perpetuate the role of a needed adversary owing to its "unashamed continuity with the communist Soviet Union."[46]

By country

Within Russia

Northern Caucasus

In a report by the Jamestown Foundation, dealing with the topic of the (extremely positive according to the report) reception of American Republican senator John McCain's statements about Russia's "double standards in the Caucasus" (referring to how Russia recognized South Ossetia but would not let Chechnya go), one Chechen stated that Chechnya "cannot exist within the borders of Russia because every 50 years... Russia kills us Chechens".[47]

Journalist Fatima Tlisova released an article in 2009 discussing the frequent occurrences of Russian Orthodox crosses being sawed off buildings and thrown off mountains in Circassia, due to the cross being associated with the people who initiated the mass expulsions of Circassians.[48]

In April 2015, Chechnya's leader Ramzan Kadyrov ordered Chechen security forces to “shoot to kill” if they encountered police officers from other parts of Russia on the territory of the Chechen Republic.[49][50]

Former Soviet Union

Armenia

According to a July 2007 poll, only 2% of Armenians see Russia as a threat, as opposed to 88% who view Russia as Armenia's partner.[51] According to Manvel Sargsyan, the Director of the Armenian Center of National and Strategic Research, "There are no special anti-Russian sentiments in Armenia."[52] Armenia's first president Levon Ter-Petrosyan stated in 2013 that anti-Russian sentiment "has never existed and still does not exist" in Armenia, except "some marginal elements and some individuals with anti-Russian sentiment."[53] During the dissolution of the Soviet Union and rise of nationalism in the Soviet republics and Eastern bloc countries, Armenian nationalists were among the few that did not "interpret Russia as their most significant threat."[54] Armenian Foreign Minister Vartan Oskanian stated in 2001 that "Anti-Soviet sentiment did not mean anti-Russian in Armenia's case."[55] In a 2015 poll, only 7% disapproved of doing business with Russians, while 91% approved.[56]

On several occasions, however, anti-Russian sentiment has been expressed in Armenia, particularly in response to real or perceived anti-Armenian actions by Russia. In June 1903, Nicholas II issued a decree ordering the confiscation of all Armenian Church properties (including church-run schools) and its transfer to the Russian Interior Ministry. The decision was perceived by Armenians to be an effort of Russification and it met widespread popular resistance by the Russian Armenian population and led by the Dashnak and Hunchak parties. This included attacks on Russian authorities in attempts to prevent the confiscation. The decree being eventually canceled in 1905.[57] In more recent times, in July 1988, during the Karabakh movement, the killing of an Armenian man and the injury of tens of others by the Soviet army in a violent clash at Zvartnots Airport near Yerevan sparked anti-Russian and anti-Soviet sentiment in the Armenian public.[58]

Azerbaijan

In Azerbaijani society, Russians are perceived mostly as invaders that have controlled Azerbaijan for almost 200 years with a two-year halfway break. For current generations, Russians are seen as direct and indirect perpetrators of the two most terrible events which have occurred in Azerbaijan's modern history.[59] One is the Black January (when Soviet soldiers entered Baku to suppress the independence movement and killed over 100 people in 1990);[60] the other is the Khojali massacre during the Karabakh War.

Georgia

According to a 2012 poll, 35% of Georgians perceive Russia as Georgia's biggest enemy, while the percentage was significantly higher in 2011, at 51%.[61] In a February 2013 poll, 63% of Georgians said Russia is Georgia's biggest political and economic threat as opposed to 35% of those who looked at Russia as the most important partner for Georgia.[62] The main reason behind this is due to long historical grievances dated back at 1990s, when Russia supported the independence of Abkhazia, causing the Abkhaz–Georgian conflict and later war with Russia in 2008.[63]

Estonia

According to veteran German author, journalist and Russia-correspondent Gabriele Krone-Schmalz, there is deep disapproval of everything Russian in Estonia.[64] A poll conducted by Gallup International suggested that 34% Estonians have a positive attitude towards Russia, but it is supposed that survey results were likely impacted by a large ethnic Russian minority in country.[15] However, in a 2012 poll only 3% of the Russian minority in Estonia reported that they had experienced a racially motivated hate crime (as compared to an average of 10% among ethnic minorities and immigrants in EU).[20]

According to Estonian philosopher Jaan Kaplinski, the birth of anti-Russian sentiment in Estonia dates back to 1940, as there was little or none during the czarist and first independence period, when anti-German sentiment predominated. Kaplinski states the imposition of Soviet rule under Joseph Stalin in 1940 and subsequent actions by Soviet authorities led to the replacement of anti-German sentiment with anti-Russian sentiment within just one year, and characterized it as "one of the greatest achievements of the Soviet authorities".[65] Kaplinski supposes that anti-Russian sentiment could disappear as quickly as anti-German sentiment did in 1940, however he believes the prevailing sentiment in Estonia is sustained by Estonia's politicians who employ "the use of anti-Russian sentiments in political combat," together with the "tendentious attitude of the [Estonian] media."[65] Kaplinski says that a "rigid East-West attitude is to be found to some degree in Estonia when it comes to Russia, in the form that everything good comes from the West and everything bad from the East";[65] this attitude, in Kaplinski's view, "probably does not date back further than 1940 and presumably originates from Nazi propaganda."[65]

Latvia

Ever since Latvia regained its independence in 1991 various Russian officials, journalists, academics and pro-Russian activists have criticised Latvia for its Latvian language law and Latvian nationality law and repeatedly accused it of "ethnic discrimination against Russians",[66] "anti-Russian sentiment"[67][68] and "Russophobia".[69] In 1993 Boris Yeltsin, President of Russian Federation and Andrei Kozyrev, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, declared that Latvia is preparing for an ethnic cleansing.[70] However, contrary to Yeltsin's and Kozyrev's claims, not a single Russian has ever been killed for political, nationalistic or racist reasons in Latvia since it regained its independence.[71][72][73]

In a 2004 research titled "Ethnic tolerance and integration of the Latvian society" conducted by the Baltic Institute of Social Sciences Latvian respondents on average rated their relations with Russians 7.8 out of 10, whereas non-Latvian respondents rated their relations with Latvians 8.4 out of 10. Both respondent groups believed the relations between them were satisfactory, had not changed in the last 5 years and were to either remain the same or improve in the next 5 years. Respondents did mention some conflicts on an ethnic basis, but all of them were classified as psycholinguistic, i.e., verbal confrontations. Most or 66% of non-Russian respondents would also support their son or daughter marrying a person of Russian ethnicity.[74] Furthermore, in a 2012 poll, only 2% of the Russian minority in Latvia reported that they had experienced a 'racially' motivated hate crime (as compared to an average of 10% among immigrants and minorities in EU).[20]

On the other hand, results of a yearly poll carried out by the research agency "SKDS" showed that the population of Latvia was more split on its attitude towards the Russian Federation. In 2008 47% percent of respondents had a more positive or positive view of Russia, while 33% had a more negative or negative one, but the rest (20%) found hard to define their view. It reached a high in 2010 when 64% percent of respondents felt more positive or positive towards Russia, in comparison with the 25 percent that felt more negative or negative. In 2015, following the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, however, it reached the lowest level since 2008 and for the first time the people with a more negative or negative attitude towards Russia (46%) surpassed people with a more positive or positive attitude (41%). In 2017 the respondents having a more positive or positive view of Russia slightly increased and reached 47%, but the respondents having a more negative or negative view of Russia decreased to 38%. The data wasn't differentiated between the respondent nationalities,[75] so it has to be noted that between 2008 and 2017 ethnic Russians made up more than a quarter of population of Latvia.

According to The Moscow Times, Latvia's fears of Russia are rooted in history, including conflicting views on whether Latvia and other Baltic States were occupied by the USSR or joined it voluntary, as well as the 1940–1941 June and 1949 March deportations that followed and most recently the annexation of Crimea that fueled a fear that Latvia could also be annexed by Russia.[76] While Russian-American journalist and broadcaster Vladimir Posner also believed the fact that many Russians in the Latvian SSR did not learn Latvian also contributed to accumulation of an "anti-Russian sentiment".[68]

On a political level Russians in Latvia do have sometimes been targeted by an anti-Russian rhetoric from some of the more radical members of both the mainstream and radical right parties in Latvia. In November 2010 correspondence from 2009 between Ģirts Valdis Kristovskis, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Latvia, and Latvian American doctor and former member of the Civic Union, Aivars Slucis was released by journalist Lato Lapsa. In one of the letters, Slucis complained of being unable to return and work in Latvia, because he "would not be able to treat Russian in the same way as Latvians" to which Kristovskis allegedly responded "I agree with your evaluation of the situation."[77]

Lithuania

For Lithuanians, Russia has never stopped their desire to consolidate power over the Baltics, which Lithuania is one of them, and feared Russia would plan for an eventual invasion against Lithuania like it did to Crimea.[78] There are also concerns over Russia's increasing military deployment, such as in Kaliningrad, an exclave of Russia bordering Lithuania.[79][80]

Moldova

Ever since the independence of Moldova, Russia has been repeatedly accused by many Moldovans, whom mostly of ethnic Romanians and Ukrainians, for meddling in Moldovan politics,[81] notably from Andrian Candu, a Moldovan senator.[82] On the other side, Russia's involvement on the pro-Russian separatists in Transnistria further strained the relations between Russia and Moldova, and Pavel Filip, Prime Minister of Moldova, has demanded Russia to quit the region.[83]

In 2018, the Parliament of Moldova “unanimously” adopted a declaration condemning the attacks coming from the Russian Federation upon the national informational security and the abusive meddling in political activity in the Republic.[84]

Ukraine

In a poll held by Kiev International Institute of Sociology in May 2009 in Ukraine, 96% of respondents were positive about Russians as an ethnic group, 93% respected the Russian Federation and 76% respected the Russian establishment.[87]

According to the statistics released on October 21, 2010 by the Institute of Sociology of National Academy of Science of Ukraine, positive attitudes towards Russians have been decreasing since 1994. In response to a question gauging tolerance of Russians, 15% of Western Ukrainians responded positively. In Central Ukraine, 30% responded positively (from 60% in 1994); 60% responded positively in Southern Ukraine (from 70% in 1994); and 64% responded positively in Eastern Ukraine (from 75% in 1994). Furthermore, 6-7% of Western Ukrainians would banish Russians entirely from Ukraine, and 7-8% in Central Ukraine responded similarly. This level of sentiment was not found in Southern or Eastern Ukraine.[88]

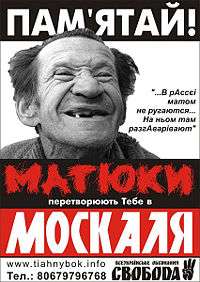

The right-wing political party "Svoboda",[85][86][89] has invoked radical Russophobic rhetoric[90] and has electoral support enough to garner majority support in local councils,[91] as seen in the Ternopil regional council in Western Ukraine.[92] Analysts explained Svoboda’s victory in Eastern Galicia during the 2010 Ukrainian local elections as a result of the policies of the Azarov Government who were seen as too pro-Russian by the voters of "Svoboda".[93][94] According to Andreas Umland, Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy,[95] Svoboda's increasing exposure in the Ukrainian media has contributed to these successes.[96] According to British academic Taras Kuzio the presidency of Viktor Yanukovich (2010–2014) fabricated this exposure in order to discredit the opposition.[97]

Oleh Tyahnybok, the leader of Svoboda, whose members held senior positions in the short-lived First Yatsenyuk government, urged his party to fight "the Moscow-Jewish mafia" ruling Ukraine.[98] For these remarks Tyahnybok was expelled from the Our Ukraine parliamentary faction in July 2004.[99] Former Right Sector's leader for West Ukraine, Oleksandr Muzychko (who died violently in March 2014[100]), has talked about fighting "communists, Jews and Russians for as long as blood flows in my veins."[101]

In April 2017 Sociological group "RATING" public opinion survey 57% expressed a very cold or cold attitude toward Russia, 17% expressed a very warm or warm attitude.[102]

Belarus

As reported by Belorussian journalist Raman Kachurka, following the 2014 Ukrainian revolution pro-Russian nationalist groups, including paramilitary cossack organisations (such as the Holy Rus' Movement, Kazachi Spas and The Orthodox Brotherhood), have become more active in Belarus, with Holy Rus' Movement even openly distributing flyers calling for the unification of the Russian World, while others have cooperated with the Belarusian authorities that Kachurka calls "a clear indication about the real level of support for pro-Russian paramilitary organisations inside the country".[103]

According to Chairman of Vitsebsk-based public association "Russian House" Andrey Herashchanka, following Euromaidan in Ukraine, tensions between Belarusians and Russia increased due to Belarusian population's majority support for Ukraine against Russia.[104] While Lukashenko's regime continues to maintain tie with Russia and even imprisoning those who criticize the Government in some Russophobic accusations.[105]

Former Eastern Bloc

Czech Republic

Czech people themselves tend to be distrustful of Russia due to the 1968 invasion led by the Soviet Union, and tend to have a negative opinion of Russians.[106][107] Russia remains continuously among the most negatively perceived countries among Czechs in polls conducted since 1991, and just 26% of Czechs responded that they have a positive opinion about Russia in November 2016.[108]

Poland

According to a 2013 BBC World Service poll, 19% of Poles viewed Russia's influence positively, with 49% expressing a negative view.[109]

According to Boris Makarenko, deputy director of the Moscow-based think tank Center for Political Technologies, much of the modern anti-Russian feelings in Poland is caused by grievances of the past.[110] One contentious issue is the massacre of 22,000 Polish officers, priests and intellectuals in Katyn Forest in 1940, and deportation of around 250,000 mostly Polish civilians and others including soldiers to Siberia and Kazakhstan where many, around 100,000 died, even though the Russian government has officially acknowledged and apologized for the atrocity.[111]

In 2005, The New York Times reported after the Polish daily Gazeta Wyborcza that "relations between the nations are as bad as they have been since the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1989."[112]

Jakub Boratyński, the director of international programs at the independent Polish think tank Stefan Batory Foundation, said in 2005 that anti-Russian feelings have substantially decreased since Poland joined the EU and NATO, and that Poles feel more secure than before, but he also admitted that many people in Poland still look suspiciously at Russian foreign-policy moves and are afraid Russia is seeking to "recreate an empire in a different form."[110]

In 2015, two Polish experts, Jolanta Darczewska and Piotr Żochowski, criticized Russia's aggressive behavior following Euromaidan in neighboring Ukraine, saying it was used to define “the zone of the Russian Empire’s domination” as well as to present a “vision of a distinct ‘Russian world’ constructed in opposition to the consumerist, ‘decaying’ West,” two themes that continue to echo to the present day and warned Russia would only end up with their own destruction, further leading to higher tensions between two countries.[113] In 2017, Poland was accused by Russia for "attempting to impose its own version of history" after Moscow was not allowed to join an international effort to renovate a World War II museum in Poland[114] and destroyed monument honoring Soviet soldiers fallen in the war.[115] Tensions between two run high when in 2018, Ukrainian officials discovered two pro-Russian and pro-Yanukovych loyalists blew up a cemetery in Lviv as an anti-Polish acts, leading to angers among Polish population over Russia.[116]

Montenegro

Since the independence of Montenegro, due to relative distance, anti-Russian sentiment isn't common among Montenegrins. However, during 2015–16 Montenegrin crisis, Montenegro almost suffered a coup which was believed to be organized by a "powerful organization" comprising 50 people from Russia, Serbia and Montenegro planned to assassinate Montenegro's Prime Minister Milo Đukanović and place a pro-Kremlin opposition party into power, said Milivoje Katnić, special prosecutor for organized crime.[117] A year later, covert surveillance photographs said to offer key proof Russian intelligence officers plotted a violent coup that would have ended in the assassination of a European leader in Montenegro,[118] leading to trial against alleged pro-Russian coup leaders.[119] According to a key witness of the trial the coup was likely linked to Russia's increasing resentment over Montenegro's desire to join the NATO.[120]

Romania

Anti-Russian sentiment dates back to the conflict between the Russian and Ottoman empires in the 18th and early 19th centuries and the ceding of part of the Moldavian principality to Russia by the Ottoman Empire in 1812 after its de facto annexation, and to the annexations during World War II and after by the Soviet Union of Northern Bukovina and Bessarabia and the policies of ethnic cleansing, Russification and deportations that have taken place in those territories against ethnic Romanians. Following WWII, Romania, an ally of Nazi Germany, was occupied by Soviet forces. Soviet dominance over the Romanian economy was manifested through the so-called Sovroms, exacting a tremendous economic toll ostensibly as war-time reparations.[121][122][123][124][125]

Croatia

At the end of 2016, Russian experts were cited as assessing Russian–Croatian relations as ″cold″.[126] Croatia is one of the anti-Russian countries in Europe, according to the voting on European Parliament's 23 November 2016 resolution.[127] Croatia's position as a member of both NATO and the European Union can be contrasted to that of traditional Russian ally Serbia,[128] with which it has strained relations.[129] Croats are Catholic and Serbs are Orthodox (as the Russians are), and during the Ukrainian crisis mercenaries of the two ethnic groups were on opposing sides, Croats fighting for Ukraine and Serbs fighting for the Russian separatists.[130][131] An article in Foreign Affairs called Croatia the strongest Western ally against Russian expansion in the Balkans.[132]

Albania

Historically, relations between Albania and Russia has been tense, due to Russia's traditional support for Serbia, Macedonia and Greece, which are majority Orthodox Christian countries and hostile against Albania. Albania is a stun ally of the West, therefore strained the relations between Albania and Russia.

A majority of Albanians perceived Russia as a threat due to Russia's blockade of Kosovo's independence recognition,[133] as well as economic combat and sanctions by Russia against Albania.[134]

Bulgaria

In 2017, Bulgarian national security named Russia as a direct threat for Bulgaria's security.[135]

Hungary

During the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, Hungarian revolutionary force almost defeated Austria until Russian Empire came to aid the Austrians and suppress the Hungarians in blood.[136] This had left a huge scar on the relations between Hungary and Russia and strained their relations. Hungary and Russia later fought against each other in both two World Wars, only saw the aftermath World War II as Hungary turned into a Soviet puppet. Hungarians once again rose up at 1956 against the Soviet-based puppet. In turn, Soviet Union deployed troops and tanks suppressing the revolution once again very bloody, leading a huge pain among Hungarian population and stemmed strong anti-Russian sentiment in the country.[137]

In modern day, although anti-Russian sentiment has no longer played a significant role, fear of Russian militarism and expansionism remain. In 2016, Russian state medias smeared the memoir of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, mocking it as a product of the United States and NATO, sparking criticisms against Russia among Hungarian population.[138] With the increasing Russian military invasion, and Viktor Orbán's close relations with Russia, it has led to the resurgence of anti-Russian sentiment in Hungary.[139]

Western world

Australia

According to the World Public Opinion poll undertaken in 2013, 53% of Australians had a negative view of Russia, up 15% from 2012.[140] Following the shooting down of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, allegedly by Russian-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine, which claimed the lives of at least 27 Australians, Prime Minister Tony Abbott considering barring Russian President Vladimir Putin from attending the 2014 G-20 Brisbane summit.[141][142]

Finland

In Finland, anti-Russian sentiment has been studied since the 1970s. The history of anti-Russian sentiment has two main theories. One of them claims that Finns and Russians have been archenemies throughout history. The position is considered to have been dominated at least the 1700s since the days of the Greater Wrath, when the Russians "occupied Finland and raped it." This view largely assumes that through the centuries, "Russia is a violent slayer and Finland is an innocent, virginal victim".[143] In the 1920s and 1930s this anti-Russian and anti-Communism propaganda had a fertile ground.[144] Failed Russian actions to terminate Finnish autonomy and cultural uniqueness (1899–1905 and 1908–1917) contributed greatly to both the anti-Russian feelings in Finland. The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which granted Finland to the Soviet Union, was followed by the attack of the Soviet Union against Finland during the Winter War and Soviet annexation of large parts of Finland. This caused high casualties among the Finns and 11% of the total population had to leave their homes, later causing great bitterness, and has endured as the Karelian question in Finnish politics.

Another theory considers anti-Russian sentiment as being born in Finland at the time of civil war 1917–1918, and the anti-Russian political and ideological White Finland created a confrontation which deliberately blew and spread the sentiment. Anti-Russian sentiment was created against the external threat of the Soviet Union and it was considered almost a national duty in the 1920s and 1930s.[145] During World War II, Finns organized internment camps in the occupied East Karelia where ethnic segregation between 'relatives' (Finnic population) and 'non-relatives' (other, primarily Russian population) took place which has been attributed to anti-Russian sentiment.

According to polls in 2004, 62% of Finnish citizens had a negative view of Russia.[15] Deportation of Ingrian Finns, indigenous to St. Petersburg, Ingria, and other Soviet repressions against its Finnish minorities have contributed to negative views of Russia. In a 2012 poll, 12% of Russian immigrants in Finland reported that they had experienced a racially motivated hate crime (as compared to an average of 10% of immigrants in the EU).[20]

Greece

In 2018, in solidarity with the United Kingdom over Russia's allegation of Sergei Skripal assassination, Greece decided to expel two Russian diplomats and banned two other from going to the country.[146]

Sweden

The Swedish words russofob (Russophobe) and russofobi (Russophobia) were first recorded in 1877 and 1904 respectively and its more frequent synonym rysskräck (fear of Russia or Russians) in 1907. Older synonyms were rysshat (hatred of Russia or Russians) from 1846 and ryssantipati (antipathy against Russia or Russians) from 1882.[147]

The Russian state is said to have been organized in the 9th century AD at Novgorod by Rurik, supposedly coming from Sweden. In the 13th century, Stockholm was founded to stop foreign navies from invading lake Mälaren. Both events are signs that hostile naval missions across the Baltic Sea go a long way back, temporarily ending with the peace treaty of Nöteborg 1323 between Sweden and the Novgorod Republic (which later became Russia), soon to be broken by another Catholic Swedish crusade into Greek-orthodox Novgorod. Russia has been described as Sweden's "archenemy" (a title also given to Denmark). The two countries have often been at war, most intensively during the Great Northern War (1700–1721) and the Finnish War (1808–1809), when Sweden lost that third of its territory to Russia that now is Finland. Sweden defeated a Russian army in the Battle of Narva (1700), but was defeated by Russia in the Battle of Poltava 1709. In 1719 Russian troops burnt most Swedish cities and industrial communities along the Baltic sea coast to the ground (from Norrköping up to Piteå in the north) in what came to be called "Rysshärjningarna" (the Russian ravages, a term first recorded in 1730[147]). "The Russians are coming" (ryssen kommer) is a traditional Swedish warning call.[148] After the death of king Charles XII in 1718 and the peace in 1721, Swedish politics was dominated by a peace-minded parliament, with a more aggressive opposition (Hats and Caps). When Swedish officer Malcolm Sinclair was murdered in 1739 by two Russian officers, the anti-Russian ballad Sinclairsvisan by Anders Odel became very popular.[149][150]

After 1809, there have been no more wars between Russia and Sweden, partly due to Swedish neutrality and nonalignment foreign policy since then. Peaceful relationships and the Russian capital being Saint Petersburg, many Swedish companies ran large businesses in Imperial Russia, including Branobel and Ericsson. Many poets still grieved the loss of Finland and called for a military revenge,[151] ideas that were refueled by the Crimean War in the 1850s.[152] With the increasing cultural exchange between neighboring countries (Scandinavism) and the nationalist revival in Finland (through Johan Ludvig Runeberg and Elias Lönnrot), contempt with the attempts of Russification of Finland spread to Sweden. Before World War I, travelling Russian saw filers were suspected of espionage by Swedish proponents of increased military spending. After the Russian Revolution in the spring of 1917 and the abdication of the Tsar, great hope was vested in the new provisional government, only to be replaced with despair after the so-called October Revolution. Old anti-Russian sentiments were compounded by a fresh element of anti-communism, to last for the duration of the existence of the Soviet Union. Many Swedes voluntarily joined the Finnish side in the Winter War between Finland and Soviet Union 1939–1940. When the Soviet state was finally dissolved in 1991, anti-communism became less relevant in terms of power politics and for some time, few seemed to recall the fear of its predecessor.

Thus, in statements made by Swedish politicians, the Swedish sentiments against the Russian government have always been about fear of military invasion, which now seemed to be gone for the foreseeable future, and also about human rights and democracy issues. Only 31% of Swedes stated that they liked Russia in 2011, and 23% in 2012, and only 10% have confidence in Russian elections.[17]

In June 2014, political scientist Sergey Markov complained about Russophobia in Sweden and Finland, comparing it to antisemitism. "Would you want to be part of starting a Third World War? Antisemitism started the Second World War, Russophobia could start a third.", he commented.[153] The retired Swedish history professor and often cited expert on Russia Kristian Gerner said he was "almost shocked" by Markov's claim, and described his worldview as "nearly paranoid".[154][155]

France

Anti-Russian sentiment was common in France after the French defeat by the Russians in the 1812 War.[156]

New Zealand

The history of early anti-Russian sentiment in New Zealand was analyzed in Glynn Barratt's book Russophobia in New Zealand, 1838-1908,[157] expanded to cover the period up to 1939 in an article by Tony Wilson.[158]

According to Wilson, negative attitude towards the Russian Empire had no roots in the country itself, but was fueled by attitude of the British Empire, at a time when New Zealand was still a British colony. It was aggravated by lack of information about Russia and contacts with it due to the mutual remoteness. Various wars involving the Russian Empire fueled the "Russian scare". Additional negative attitude was brought by Jewish immigration after Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire. That immigration was halted as a combined result of Russophobia and anti-Semitism. As of 1916, there were 1242 settlers of Russian origin in the country, including 169 Jews. During World War I anti-Russian sentiment was temporarily supplanted by anti-German sentiment for evident reasons; however, soon after the Russian Revolution of 1917, the fear of Marxism and Bolshevism revived Russophobia in the form of "Red Scare". Notably, local Russians had no issues with Russophobia. By late 1920s pragmatism moderated anti-Russian sentiment in official circles, especially during the Great Depression. Sympathetic views were propagated by visitors to the Soviet Union, such as George Bernard Shaw, impressed by Soviet propaganda.[158]

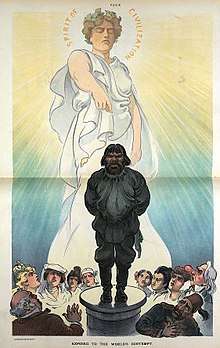

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, anti-Russian sentiment arose during conflicts including the Crimean War[159] and the Anglo-Afghan wars, which were seen as representing Russia's territorial ambitions regarding the British empire in India. This competition for spheres of influence and colonies (see e.g. The Great Game and Berlin Congress) fueled anti-Russian sentiment in Britain. British propaganda at the time took up the theme of Russians as uncultured Asiatic barbarians.[160] The American professor Jimmie E. Cain Jr has stated that these views were then exported to other parts of the world and were reflected in the literature of late the 19th and early 20th centuries.[159]

Canada

While Russia and Canada have little contact to each other, anti-Russian sentiment has increased in Canada as for the result of Soviet Union's militarism and its communist expansions. Recently, the trend of negative impression on Russia remains high in Canada due to alleged Putin's interference in the Western politics, human rights issue, including the assassination attempt on Sergei Skripal,[161] the rise of anti-Russian PM Justin Trudeau, large Ukrainian Canadian population in Canada whom hold strong disdain on Russia[162] or notably, the appointment of Chrystia Freeland, an anti-Russian Foreign Minister.

At the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, Canada had called for a ban of Russian athletes entering the Olympics.

United States

During the Cold War years, there was frequent confusion and conflation of terms "Russians" and "Communists"/"Soviets"; in 1973, a group of Russian immigrants in the US founded the Congress of Russian Americans with the purpose of drawing a clear distinction between Russian national identity and Soviet ideology, and preventing the formation of anti-Russian sentiment on the basis of Western anti-communism.[163] Members of the Congress see the conflation itself as Russophobic, believing "Russians were the first and foremost victim of international Communism".[164]

According to a 2013 Poll, 59% of Americans had a negative view of Russia, 23% had a favorable opinion, and 18% were uncertain.[140] According to a survey by Pew Research Center, negative attitudes towards Russia in the United States rose from 43% to 72% from 2013 to 2014.[18]

Recent events such as the Anti-Magnitsky bill,[165] the Boston Marathon bombings[166] Russia's actions following the Ukrainian crisis,[18] the Syrian Civil War, the allegations of Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections and the allegations of collusion between Donald Trump's presidential campaign and Russia[167][168] are deemed to have caused a rising negative impression about Russia in the United States.

In December 2016, New York Daily News columnist Gersh Kuntzman compared the assassination of the Russian Ambassador to Turkey, Andrei Karlov, to the assassination of German diplomat Ernst vom Rath by Jewish student Herschel Grynszpan, saying "justice has been served."[169]

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Glenn Greenwald of The Intercept wrote in February 2017 that the "East Coast newsmagazines" are "feeding Democrats the often xenophobic, hysterical Russophobia for which they have a seemingly insatiable craving."[170]

In May 2017, former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper said on NBC's Meet The Press that Russians were "almost genetically driven" to act deviously.[171][172] Freelance journalist Michael Sainato criticized the remark as xenophobic.[173]

Hollywood

In a 2014 news story, Fox News reported, "Russians may also be unimpressed with Hollywood’s apparent negative stereotyping of Russians in movies. "The Avengers" featured a ruthless former KGB agent, "Iron Man 2" centers on a rogue Russian scientist with a vendetta, and action thriller "Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit" saw Kenneth Branagh play an archetypal Russian bad guy, just to name a few."[174]

Norway

Norway traditionally isn't commonly a Russophobe country; however, it shares historical tie with Nordic nations like Sweden, Finland and Denmark which have experienced conflicts against Russia, as well as being a NATO member, and thus anti-Russian sentiment also exists in Norway. Norway shared solidarity with Finland and Sweden during the Cold War against Soviet Union, its tie to the West thus complicated the relations with Russia continues.[175][176]

Recently, tensions with Russia is mainly over Russia's militaristic involvements in Ukraine and Georgia, which Norway supported sanctions against Russia and has not lifted it;[177] Russian expansionism in North Pole;[178] military buildup in Norway over fear of Russian takeover and hosting the U.S. Marines in the country even deteriorated relations between Norway and Russia.

In 2017, Russian Embassy in Oslo had shown dissatisfaction of the relations over what it perceived to be "mythical Russian threat" over disinformation of Russian alleged involvements. In response, Prime Minister Erna Solberg, informed of the harsh Russian criticism of Norway while attending the Munich Security Conference, seemed to be taking it in stride. “This is an example of Russian propaganda that often comes when there’s a focus on security policy. There is nothing in this that’s new to us.”[179]

Denmark

Increasing tensions between Denmark and Russia began when in August 2014, the Danish government announced that it would contribute to NATO's missile defense shield by equipping one or more of its frigates with radar capacity, amid the Ukrainian crisis and growing tensions between Russia and NATO.[180] On March 22, 2015, the Russian ambassador to Denmark, Mikhail Vanin, confirmed the tensions during an interview to Jyllands-Posten: "I do not think Danes fully understand the consequences of what happens if Denmark joins the US-led missile defense. If this happens, Danish warships become targets for Russian nuclear missiles". Denmark's foreign minister, Martin Lidegaard, announced the ambassador's remarks as unacceptable and that the defense system was not aimed at Russia, a claim echoed by NATO's spokeswoman, Oana Lungescu. NATO's spokesman added that the Russian statements "do not inspire confidence or contribute to predictability, peace or stability".[181][182]

Rest of the world

Ethiopia

Due to the Soviet Union's involvement in the Ethiopian Civil War on the side of Communist Derg, a strong anti-Russian/Soviet sentiment developed by the anti-communist Ethiopians, since Soviet Union had, indirectly, involved in the Red Terror of Ethiopia and supporting for Mengistu Haile Mariam who was later found guilty for the terror.[183][184]

Vietnam

From 2010s onward, the younger and middle generations are becoming aware of Russian atrocities towards its neighbors like Belarus, Germany, Ukraine and Poland, notably rape of Eastern European and German women by Russian troops, or the Katyń Massacre, which have sparked strong anti-Russian sentiment among Vietnamese population.[185] Recent good relationship between China and Russia, the former has been Vietnam's long time adversary for years, the failure of the Soviet Union to assist Vietnam at the 1979 Sino–Vietnamese War and poor treatments and repeated killing of Vietnamese in Russia also contributed to the backlash against Russia rising among Vietnamese population, especially Southern Vietnamese.[186]

Overseas Vietnamese, mostly descendants of the South Vietnamese refugees, as well as recent Vietnamese immigrants moving abroad, perceive Russia as a direct threat of Vietnamese sovereignty after China.[187]

South Korea

Due to the history of the Cold War and the Korean War, where the Soviet Union and South Korea fought on opposing sides, relations between Russia and South Korea have been almost non existent until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Even so, opinion about Russia and Russians in South Korea remains low, particularly due to Russia's support for North Korea.[188]

Venezuela

Anti-Russian sentiment has been increasing in Venezuela due to Russia's support to Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro during the Venezuelan crisis, which the opposition, strongly anti-Russian, are hostile toward Russia.[189]

China

China and Russia had been at war in the past. Russia and China both had historical expansions, which later led to war between two nations. The Russians later invaded Central Asia, and drove the Chinese out of Outer Manchuria which had been annexed by Russia and eventually, belongs to Russia today. Russia and China even later went to some fierce border clash during the communist era of Soviet Union, and border conflict which almost resulted by using nuclear bomb from the Soviet Union against China.[190] Today, there is no more border disputes as all were settled in 2004, however fears about Russia's military involvement remains relevant in China.

Syria

Throughout the Syrian Civil War, the Syrian opposition is one of the most Russophobic group in Syria. Their main accusation is because of Russian military involvement on Bashar al-Assad's side, Russia's continuous rejection of any wrongdoing throughout the Syrian War[191] further strained relations between anti-Assad groups and Russia. Russophobia often goes with Iranophobia in Syria when the Syrian conflict escalates, mainly due to Assad and the United States involvement against Syrian Armed Forces.[192]

Iran

In the first half of the 19th century, Russia annexed large parts of Iranian territory in the Caucasus; by the Treaty of Gulistan (1813) and Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), Iran was forced to cede what is present-day Azerbaijan, Armenia, eastern Georgia and southern Dagestan to Russia. These territories had made part of the concept of Iran for centuries.[193] As a result of the subsequent rampant anti-Russian sentiment, on 11 February 1829, an angry mob stormed the Russian embassy in Tehran and slaughtered almost everyone inside. Among those killed in the massacre was the newly appointed Russian ambassador to Iran, Aleksander Griboyedov, a celebrated playwright. Griboyedov had previously played an active role in negotiating the terms of the treaty of 1828.[194] Russia was seen as an invader who destroyed, forcefully converted and demolished Iranian heritages in occupied territories.[195]

During 20th century, Russia as USSR had involved in Azerbaijani and Kurdish separatist movements, making Russophobia grew rapidly in Iran. This remains high since despite recent Islamic Government tried to silence its dissidents over it.[196]

Due to Russia's support of the Iranian government, many protesters started chants of "Death to Russia" after the 2009 Presidential election.[197]

Somalia

Anti-Russian/Soviet sentiment started in Somalia when the USSR condemned Somali invasion of Ogaden during the Ogaden War and even sent troops to fight for Communist Ethiopia against Somalia. Throughout the Ogaden War, Somalia was one of the strongest Russophobic nations in Africa and the world.[198]

Turkey

According to a 2013 survey 73% of Turks look at Russia unfavorably against 16% with favorable views.[199]

Historically, Russia and Turkey fought a number of war and had caused a great devastation for each nation. During the old Tsardom of Russia, the Ottomans often raided and attacked Russian villagers. With the transformation into Russian Empire, Russia started to expand and clashed heavily with the Turks; which Russia often won more than lost, and reduced the Ottoman Empire heavily. The series of wars had manifested the ideas among the Turks that Russia wanted to turn Turkey into a vassal state, leading to a high level of Russophobia in Turkey.[200] In the 20th century, anti-Russian sentiment in Turkey was so great that the Russians refused to allow a Turkish military attache to accompany their armies.[201] After the World War I, both Ottoman and Russian Empires collapsed, and two nations went on plagued by their own civil wars; during that time Soviet Russia (who would later become Soviet Union) supported Turkish Independence Movement led by Mustafa Kemal, leading to a warmer relations between two states, as newly established Turkish Republic maintained a formal tie with Soviet Union.[202] But their warm relations didn't last long; after the World War II, the Bosphorus crisis occurred at 1946 due to Joseph Stalin's demand for a complete Soviet control of the straits led to resurgence of Russophobia in Turkey.[203]

Anti-Russian sentiment started to increase again since 2011 following with the event of the Syrian Civil War. Russia supports the Government of Bashar al-Assad, whilst Turkey supports the Free Syrian Army and had many times announced their intentions to overthrow Assad, once again strained the relations.[204] Relations between two further went downhill after Russian jet shootdown by Turkish jet,[205] flaring that Russia wanted to invade Turkey over Assad's demand; and different interests in Syria. Turkish medias have promoted Russophobic news about Russian ambitions on Syria, and this has been the turning point of remaining poor relations although two nations have tried to reapproach their differences. Turkish military operations in Syria against Russia and Assad-backed forces also damage the relations deeply.[206]

Japan

Most Japanese interaction with Russian individuals – besides in major cities such as Tokyo – happens with seamen and fishermen of the Russian fishing fleet, therefore Japanese people tend to carry the stereotypes associated with sailors over to Russians.[207][208] According to a 2012 Pew Global Attitudes Project survey, 72% of Japanese people view Russia unfavorably, compared with 22% who viewed it favorably, making Japan the most anti-Russian country surveyed.[209]

Afghanistan

Grievances against Russia in Afghanistan dated back from the Soviet Union's conquest of Afghanistan. Moscow's attempt to put Afghanistan under its communist influence bearing the name of Democratic Republic of Afghanistan fueled the anti-Russian resistance in Afghanistan led by Ahmad Shah Massoud. Today, Russia is still being seen among Afghans as perpetrator of what would be, the path of tragedy for Afghanistan.[210][211]

Business

In May and June 2006, Russian media cited discrimination against Russian companies as one possible reason why the contemplated merger between the Luxembourg-based steelmaker Arcelor and Russia's Severstal did not finalize. According to the Russian daily Izvestiya, those opposing the merger "exploited the 'Russian threat' myth during negotiations with shareholders and, apparently, found common ground with the Europeans",[212] while Boris Gryzlov, speaker of the State Duma observed that "recent events show that someone does not want to allow us to enter their markets."[213] On 27 July 2006, The New York Times quoted the analysts as saying that many Western investors still think that anything to do with Russia is "a little bit doubtful and dubious" while others look at Russia in "comic book terms, as mysterious and mafia-run."[214]

View of Russia in Western media

Some Russian and Western commentators express concern about a far too negative coverage of Russia in Western media (some Russians even describe this as a "war of information").[215][216] In April 2007, David Johnson, founder of the Johnson's Russia List, said in interview to the Moscow News: "I am sympathetic to the view that these days Putin and Russia are perhaps getting too dark a portrayal in most Western media. Or at least that critical views need to be supplemented with other kinds of information and analysis. An openness to different views is still warranted."[217]

In 1995, years before Vladimir Putin was elected to his first term, the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press reported: "coverage of Russia and its president, Boris Yeltsin, was decidedly negative, even though national polls continue to find the public feeling positive toward Russia and largely uncritical of Yeltsin."[218]

In February 2007, the Russian creativity agency E-generator put together a "rating of Russophobia" of Western media, using for the research articles concerning a single theme—Russia's chairmanship of G8, translated into Russian by InoSmi.Ru. The score was composed for each edition, negative values granted for negative assessments of Russia, and positive values representing positive ones. The top in the rating were Newsday (−43, U.S.), Financial Times (−34, Great Britain), The Wall Street Journal (−34, U.S.), Le Monde (−30, France), while editions on the opposite side of the rating were Toronto Star (+27, Canada) and "The Conservative Voice"[219] (+26, U.S.).[220][221]

California-based international relations scholar Andrei Tsygankov has remarked that anti-Russian political rhetoric coming from Washington circles has received wide echo in American mainstream media, asserting that "Russophobia's revival is indicative of the fear shared by some U.S. and European politicians that their grand plans to control the world's most precious resources and geostrategic sites may not succeed if Russia's economic and political recovery continues."[222]

In practice, anti-Russian political rhetoric usually puts emphasis on highlighting policies and practices of the Russian government that are criticised internally - corruption, abuse of law, censorship, violence and intervention in Ukraine. Western criticism in this aspect goes in line with Russian independent anti-government media such as (TV Rain, Novaya Gazeta, Ekho Moskvy, The Moscow Times) and opposition human rights activists (Memorial). In defence of this rhetoric, some sources critical of the Russian government claim that it is Russian state-owned media and administration who attempt to discredit the "neutral" criticism by generalizing it into indiscriminate accusations of the whole Russian population - or Russophobia.[13][223][224] Some have argued, however, that the Western media doesn't make enough distinction between Putin's regime and Russia and the Russians, thus effectively vilifying the whole nation.[225][226]

Derogatory terms

There are a variety of derogatory terms referring to Russia and Russian people. Many of these terms are viewed as racist. However, these terms do not necessarily refer to the Russian ethnicity as a whole; they can also refer to specific policies, or specific time periods in history.

In English

- Russkie.

- Russcunt.

- The Russians are coming — it was derived from Swedish's "ryssen kommer". It became widely popular since translated to English at late 19th century, to describe threat from Russia.

In Polish

- Moskal — it was used as a historical designation used for the residents of the Grand Duchy of Moscow from the 12th-18th centuries, which have originated from Poland and Ukraine.[227] Today it has become an ethnic slur referring to the Russians living in Russia used in Ukraine, Belarus,[227] and Poland.[228]

In Czech

In Swedish

- Ryssen kommer — literally "the Russians are coming", used after the Great Northern War. It was soon translated to English and become a popular call, over the Russian threat.

In Ukrainian

- Москалі (Moskali) — literally "Moskal" in Ukrainian, in reference to Russians in global in negative term.

- Кацапи (Katsapi) — meaning "goatee beard" or "butcher", used in regard to Russians as "shopkeeper" in derogatory term.

In Chinese

- 匪俄 (Fěi é) — literally "bandit Russia", used in Nationalist China in the martial rule after retreating to Taiwan, in the same sense as the term "共匪" (communist bandit) for Communist China.[231]

Russian nationalist ideology

The issue of anti-Russian sentiment has become an indispensable part of contemporary Russian nationalist ideology.[13][232] Sociologist Anatoly Khazanov states that there's a national-patriotic movement which believes that there's a "clash of civilizations, a global struggle between the materialistic, individualistic, consumerist, cosmopolitan, corrupt, and decadent West led by the United States and the idealist, collectivist, morally and spiritually superior Eurasia led by Russia."[233] In their view, the United States want to break up Russia and turn it into a source of raw materials. The West being accused of Russophobia is a major part of their belief.[234]

See also

References

- ↑ "Художник Елена Хейдиз и ее цикл «Химеры», возмутивший шовинистов", Radio Liberty, Russian edition, May 7, 2008

- ↑ "thefreedictionary". thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ "Russophobia". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ↑ "Envoy complains Britons mistreat Russians". Reuters. July 8, 2007. Archived from the original on February 21, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- ↑ Steele, Jonathan (June 30, 2006). "The west's new Russophobia is hypocritical - and wrong". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 2, 2007.

- ↑ Forest, Benjamin; Johnson, Juliet; Till, Karen (September 2004). "Post-totalitarian national identity: public memory in Germany and Russia". Social & Cultural Geography. Taylor & Francis. 5 (3): 357–380. doi:10.1080/1464936042000252778.

- ↑ Macgilchrist, Felicitas (January 21, 2009). "Framing Russia: The construction of Russia and Chechnya in the western media". Europa-Universitat Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder). Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ Le, E´lisabeth (2006). "Collective Memories and Representations of National Identity in Editorials: Obstacles to a renegotiation of intercultural relations" (PDF). Journalism Studies. 7 (5): 708–728. doi:10.1080/14616700600890372.

- ↑ Mertelsmann, Olaf. "How the Russians Turned into the Image of the 'National Enemy' of the Estonians" (PDF). Estonian National Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 24, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ↑ Luostarinen, Heikki (May 1989). "Finnish Russophobia: The Story of an Enemy Image". Journal of Peace Research. 26 (2): 123–137. doi:10.1177/0022343389026002002. JSTOR 423864.

- ↑ Kurutz, Steven (January 17, 2014). "Russians: Still the Go-To Bad Guys". The New York Times. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Umland, Andreas (January 21, 2016). "The Putinverstehers' Misconceived Charge of Russophobia: How Western Apology for the Kremlin's Current Behavior Contradicts Russian National Interests". Harvard International Review. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Darczewska, Jolanta; Żochowsky, Piotr (October 2015). "Russophobia in the Kremlin's strategy: A weapon of mass destruction" (PDF). Point of View. OSW Centre for Eastern Studies (56). ISBN 978-83-62936-72-4. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Publics Worldwide Unfavorable Toward Putin, Russia". Pew Research Center. August 16, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Helsingin Sanomat, October 11, 2004, International poll: Anti-Russian sentiment runs very strong in Finland. Only Kosovo has more negative attitude

- ↑ World Doesn't Like Russia or the U.S., Survey Shows, Moscow Times, October 13, 2014

- 1 2 "Survey: Respondents' Views on Other Countries Shift or Remain Static". Transatlantic Trends. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Russia's Global Image Negative amid Crisis in Ukraine". Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ Robinson, Piers (August 2, 2016). "Russian news may be biased – but so is much western media - Piers Robinson". the Guardian.

- 1 2 3 4 Pressrelase and Fact sheet for the study "Hate crime in the European Union" by EU Fundamental Rights Agency November 2012

- ↑ EU-MIDIS, European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey: Minorities as victims of crime (PDF). European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ↑ Lloyd S. Kramer (2000). Lafayette in Two Worlds: Public Cultures and Personal Identities in an Age of Revolutions. p. 283.

- ↑ Neumann, Iver B. (2002). Müller, Jan-Werner, ed. Europe's post-Cold War memory of Russia: cui bono?. Memory and power in post-war Europe: studies in the presence of the past. Cambridge University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-5210-0070-3.

- ↑ McNally, Raymond T. (April 1958). "The Origins of Russophobia in France: 1812-1830". American Slavic and East European Review. 17 (2): 173–189. doi:10.2307/3004165. JSTOR 3004165.

- ↑ Neumann (2002), p. 133.

- ↑ Latham, Edward (1906). Famous Sayings and Their Authors: A Collection of Historical Sayings in English, French, German, Greek, Italian, and Latin. Swan Sonnenschein. p. 181.

- ↑ Bartlett's Roget's Thesaurus. Little Brown & Company. 2003. ISBN 9780316735872.

- ↑ John Howes Gleason, The Genesis Of Russophobia In Great Britain (1950) pp 16-56.

- ↑ Barbara Jelavich, St. Petersburg and Moscow: Tsarist and Soviet Foreign Policy, 1814–1974 (1974) p 200

- ↑ Ширинянц А.А., Мырикова А.В. «Внутренняя» русофобия и «польский вопрос» в России XIX в. Проблемный анализ и государственно-управленческое проектирование. № 1 (39) / том 8 / 2015. С. 16

- ↑ Ширинянц А.А., Мырикова А.В. «Внутренняя» русофобия и «польский вопрос» в России XIX в. Проблемный анализ и государственно-управленческое проектирование. № 1 (39) / том 8 / 2015. С. 15

- ↑ Odesskii, Mikhail Pavlovich (2015). Антропология культуры [Anthropology of culture] (in Russian) (3rd ed.). LitRes. pp. 201–202. ISBN 978-5-457-36929-0. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ↑ Shafarevich, Igor (Mar 1990). Russophobia. Joint Publications Research Service.

- ↑ Fisher, David C. "Russia and the Crystal Palace 1851" in Britain, the Empire, and the World at the Great Exhibition of 1851 ed. Jeffery A. Auerbach & Peter H. Hoffenberg. Ashgate, 2008:pp. 123-124.

- ↑ A Short View of Russia, Essays in Persuasion, (London 1932) John Maynard Keynes, 297-312

- ↑ "The So-Called Russian Soul"

- ↑ R. J. Overy (2004). The dictators: Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Russia. W. W. Norton. p. 537. ISBN 978-0-393-02030-4.

- ↑ Wette, Wolfram (2009). The Wehrmacht: history, myth, reality. Harvard University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-674-04511-8.

- ↑ Müller, Rolf-Dieter, Gerd R. Ueberschär, Hitler's War in the East, 1941–1945: A Critical Assessment, Berghahn Books, 2002, ISBN 1-57181-293-8, page 244

- ↑ Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, Volume One - A Reckoning, Chapter XIV: Eastern Orientation or Eastern Policy

- ↑ Adam Jones (2010), Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction (2nd ed.), p.271. – "'" Next to the Jews in Europe," wrote Alexander Werth', "the biggest single German crime was undoubtedly the extermination by hunger, exposure and in other ways of . . . Russian war prisoners." Yet the murder of at least 3.3 million Soviet POWs is one of the least-known of modern genocides; there is still no full-length book on the subject in English. It also stands as one of the most intensive genocides of all time: "a holocaust that devoured millions," as Catherine Merridale acknowledges. The large majority of POWs, some 2.8 million, were killed in just eight months of 1941–42, a rate of slaughter matched (to my knowledge) only by the 1994 Rwanda genocide."

- ↑ Russian: Политика геноцида, Государственный мемориальный комплекс «Хатынь»

- ↑ Stein, George H (1984). The Waffen SS: Hitler's Elite Guard at War, 1939–1945. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0-8014-9275-0.

- ↑ "Remarks By Heinrich Himmler"

- ↑ Peter Lavelle is a host of CrossTalk show at RT.Peter Lavelle; et al. (July 8, 2005). "RP's Weekly Experts' Panel: Deconstructing "Russophobia" and "Russocentric"". Russia Profile. Archived from the original on June 12, 2006. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- ↑ Western treatment of Russia signifies erosion of reason Dr. Vlad Sobell, 2007

- ↑ "McCain's Call to Recognize Chechen Independence Has Inspired Chechens". The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 2012-01-13. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ Tlisova, Fatima (21 August 2009). "The Role of the Russian Orthodox Church in the North Caucasus". Eurasia Daily Monitor. 6 (162). Archived from the original on December 26, 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ↑ "'Pro-Russia' Chechen leader threatens to kill Russian cops on his turf". Csmonitor.com. 23 April 2016.

- ↑ "Chechen leader Kadyrov 'threatens whole of Russia', opposition says". The Guardian. 26 February 2016.

- ↑ "Armenia National Voter Study July 2007" (PDF). IRI, USAID, Baltic Surveys Ltd./The Gallup Organization, ASA. p. 45. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ "Video Bridge - V. Putin's State Visit to Armenia on December 2, 2013". Public Dialogues. 9 December 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ "'With regard to anti-Russian sentiments, unfortunately, I consider the thoughts of the first president unrelated or misleading from the subject.'". Aravot. December 23, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ↑ Abdelal, Rawi (2005). National Purpose in the World Economy: Post-Soviet States in Comparative Perspective. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9780801489778.

- ↑ "East meets West in the Caucasus". BBC News. July 22, 2001. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Approval of doing business with Russians (%)". 2015 Armenia. Caucasus Barometer.

- ↑ Batalden, Stephen K.; Batalden, Sandra L. (1997). The Newly Independent States of Eurasia: Handbook of Former Soviet Republics (2nd ed.). Phoenix: Oryx. p. 99. ISBN 9780897749404.

- ↑ Cohen, Ariel (1998). Russian Imperialism: Development and Crisis. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 135. ISBN 9780275964818.

At his funeral, the Armenians erupted in anti-Russian and anti-Soviet demonstrations.

- ↑ Huseynov, Rusif (February 29, 2016). "Azerbaijan: Time to Choose Side". The Politicon. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ Hunter, Shireen T. (2013). "The Evolution of the Foreign Policy of the Transcaucasian States". In Bertsch, Gary K.; Cassady B. Craft; Scott A. Jones; Michael D. Beck. Crossroads and Conflict: Security and Foreign Policy in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Routledge. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-136-68445-6. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ↑ Kempe, Iris, ed. (June 17, 2013). "The South Caucasus Between The EU And The Eurasian Union" (PDF). Caucasus Analytical Digest. Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Bremen and Center for Security Studies, Zürich (51–52): 20–21. ISSN 1867-9323. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Georgian National Study February 18 – 27, 2013" (PDF). International Republican Institute, Baltic Surveys Ltd., The Gallup Organization, The Institute of Polling And Marketing. February 2013. p. 35. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ↑ Levy, Clifford J. "Russia Backs Independence of Georgian Enclaves".

- ↑ Krone-Schmalz, Gabriele (2008). "Zweierlei Maß". Was passiert in Russland? (in German) (4 ed.). München: F.A. Herbig. pp. 45–48. ISBN 978-3-7766-2525-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Subrenat, Jean-Jacques, ed. (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 273. ISBN 90-420-0890-3. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ↑ Tsygankov, Andrei (2009). Russophobia: Anti-Russian Lobby and American Foreign Policy. Palgrave MacMillan. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-230-61418-5.

- ↑ "Aven: no anti-Latvian sentiment in Russia, but anti-Russian sentiment can be observed in Latvia". The Baltic Times. July 20, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- 1 2 "Posner explained the anti-Russian sentiment in Latvia". The Quebec Post. July 8, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ↑ "Latvia blamed for Russophobia". Baltic News Network. March 22, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ↑ Latvia; Yeltsin Accuses Latvia of Preparing for 'Ethnic Cleansing'; Talks BBC Summary of World Broadcasts, April 29, 1993

- ↑ Human Rights and Democratization in Latvia. Implementation of the Helsinki Accords. United States Congress, Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. 1993. p. 6.

Russian officials, including Yeltsin and Kozyrev, have even used the term "ethnic cleansing" to describe Latvian and Estonian policies, despite the total absence of inter-ethnic bloodshed.

- ↑ Rislakki, Jukka (2008). The Case for Latvia: Disinformation Campaigns Against a Small Nation. Rodopi. p. 37. ISBN 978-90-420-2424-3.

Not a single Russian or Jew has ever been wounded or killed for political, nationalistic or racist reasons during the new independence of Latvia.

- ↑ Clemens Jr., Walter C. (2001). The Baltic Transformed: Complexity Theory and European Security. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 130. ISBN 978-08-476-9858-5.

But no one died in the Baltics in the 1990s from ethnic or other political fighting, except for those killed by Soviet troops in 1990–1991.

- ↑ "Ethnic tolerance and integration of the Latvian society" (PDF). Baltic Institute of Social Sciences. 2004. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ↑ "More people are evaluating EU more positively; attitude towards Russia is becoming more negative" (in Latvian). Public broadcasting of Latvia. October 18, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Latvia's Russia Fears Rooted in History". The Moscow Times. June 14, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ↑ Wodak, Ruth; Mral, Brigitte; Khosravinik, Majid (2013). Comparing Radical-Right Populism in Estonia and Latvia. Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse. London/New York: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 242. ISBN 978-1-78093-245-3.

- ↑ Graham-Harrison, Emma; Boffey, Daniel (April 3, 2017). "Lithuania fears Russian propaganda is prelude to eventual invasion". the Guardian.

- ↑ ERR (February 5, 2018). "Lithuania: Russia permanently stationing Iskander missiles in Kaliningrad".

- ↑ EndPlay (February 5, 2018). "Lithuania: Russia deploying more missiles into Kaliningrad".

- ↑ "Can Merkel End Russian Meddling in Moldova?".

- ↑ "Senior Official Accuses Russia Of Meddling In Moldovan Politics". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty.

- ↑ "Moldovan PM Renews Call For Russia To Quit Transdniester". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty.

- ↑ "Moldova Parliament condemns Russia's attacks on national informational security, meddling in internal politics - Moldova.org". www.moldova.org.

- 1 2 The Christian Science Monitor. "Ukraine's orange-blue divide". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- 1 2 Sewall, Elisabeth (16 November 2006). "David Duke makes repeat visit to controversial Kyiv university". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on April 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Россияне об Украине, украинцы о России - Левада-Центр". Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Institute of Sociology: Love for Russians dwindling in Western Ukraine". zik. Archived from the original on 2011-08-09. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ↑ "Tiahnybok considers 'Svoboda' as the only right-wing party in Ukraine", Hazeta po-ukrainsky, 06.08.2007. edition, edition

- ↑ UKRAINIAN APPEALS TO ANTI-SEMITISM IN ELECTION WIN, Internet Centre Anti-Racism Europe (November 4, 2010)

- ↑ (in Ukrainian) Вибори: тотальне домінування Партії регіонів, BBC Ukrainian (November 6, 2010)

- ↑ (in Ukrainian) Генеральна репетиція президентських виборів: на Тернопільщині стався прогнозований тріумф націоналістів і крах Тимошенко, Ukrayina Moloda (March 17, 2009)

- ↑ Nationalist Svoboda scores election victories in western Ukraine, Kyiv Post (November 11, 2010)

- ↑ (in Ukrainian) Підсилення "Свободи" загрозою несвободи, BBC Ukrainian (November 4, 2010)

- ↑ On the move: Andreas Umland, Kyiv – Mohyla Academy, Kyiv Post (September 30, 2010)

- ↑ Ukraine right-wing politics: is the genie out of the bottle?, openDemocracy.net (January 3, 2011)