Eurasianism

_and_near_abroad.png)

Eurasianism (Russian: Евразийство, Yevraziystvo) is a political movement in Russia, formerly within the primarily Russian émigré community, that posits that Russian civilisation does not belong in the "European" or "Asian" categories but instead to the geopolitical concept of Eurasia. Originally developing in the 1920s, the movement was supportive of the Bolshevik Revolution but not its stated goals of enacting communism, seeing the Soviet Union as a stepping stone on the path to creating a new national identity that would reflect the unique character of Russia's geopolitical position. The movement saw a minor resurgence after the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the 20th century, and is mirrored by Turanism in Turkic and Uralic nations.

Early 20th century

.svg.png)

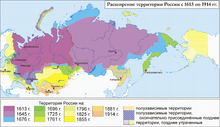

Eurasianism is a political movement that has its origins in the Russian émigré community in the 1920s. The movement posited that Russian civilization does not belong in the "European" category (somewhat borrowing from Slavophile ideas of Konstantin Leontyev), and that the October Revolution of the Bolsheviks was a necessary reaction to the rapid modernization of Russian society. The Eurasianists believed that the Soviet regime was capable of evolving into a new national, non-European Orthodox Christian government, shedding the initial mask of proletarian internationalism and militant atheism (which the Eurasianists were strongly opposed to).

The Eurasianists criticized the anti-Bolshevik activities of organizations such as ROVS, believing that the émigré community's energies would be better focused on preparing for this hoped for process of evolution. In turn, their opponents among the emigres argued that the Eurasianists were calling for a compromise with and even support of the Soviet regime, while justifying its ruthless policies (such as the persecution of the Russian Orthodox Church) as mere "transitory problems" that were inevitable results of the revolutionary process.

The key leaders of the Eurasianists were Prince Nikolai Trubetzkoy, P.N. Savitsky, P.P. Suvchinskiy, D. S. Mirsky, K. Čcheidze, P. Arapov, and S. Efron. Philosopher Georges Florovsky was initially a supporter, but backed out of the organization claiming it "raises the right questions", but "poses the wrong answers". A significant influence of the doctrine of the Eurasianists can be found in Nikolai Berdyaev's essay "The Sources and Meaning of Russian Communism".

Several organizations similar in spirit to the Eurasianists sprung up in the emigre community at around the same time, such as the pro-Monarchist Mladorossi and the Smenovekhovtsi.

Several members of the Eurasianists were affected by the Soviet provocational TREST operation, which had set up a fake meeting of Eurasianists in Russia that was attended by the Eurasianist leader P.N. Savitsky in 1926 (an earlier series of trips were also made two years earlier by Eurasianist member P. Arapov). The uncovering of the TREST as a Soviet provocation caused a serious morale blow to the Eurasianists and discredited their public image. By 1929, the Eurasianists had ceased publishing their periodical and had faded quickly from the Russian émigré community.

Late 20th century

The ideology of the movement was partially incorporated into a new movement of the same name after the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union, when the Eurasia Party was founded by Aleksandr Dugin.

Neo-Eurasianism

Neo-Eurasianism (Russian: неоевразийство) is a Russian school of thought, popularized in Russia during the years leading up to and following the collapse of the Soviet Union, that considers Russia to be culturally closer to Asia than to Western Europe.

The school of thought takes its inspiration from the Eurasianists of the 1920s, notably Prince Nikolai Trubetzkoy while P.N. Savitsky. Lev Gumilev is often cited as the founder of the Neo-Eurasianist movement, and he was quoted as saying that "I am the last of the Eurasianists."[1]

At the same time, major differences have been noted between Gumilev's work and those of the original Eurasianists.[1] Gumilev's work is controversial for its scientific methodology (the use of his own conception of ethnogenesis and the notion of "passionarity" of ethnoses). At any rate, Gumilev's work has been a source of inspiration for the Neo-Eurasianist authors, the most prolific of whom is Aleksandr Dugin.

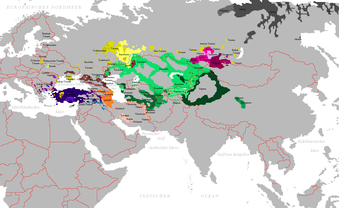

Gumilev's contribution to Neo-Eurasianism lies in the conclusions he reaches from applying his theory of ethnogenesis: that the Mongol occupation of 1240–1480 AD (known as the "Mongol yoke") had shielded the emergent Russian ethnos from the aggressive neighbor to the West, allowing it to gain time to achieve maturity. The idea of Eurasianism contrasts with Konstantin Leontyev's Byzantism, which is similar in its rejection of the West, but identifies with the Byzantine Empire rather than with Central Asian tribal culture.

"Greater" Russia

The political-cultural concept espoused by some in Russia is sometimes called the Greater Russia and is described as a political aspiration of pan-Russian nationalists and irredentists to retake some or all of the territories of the other republics of the former Soviet Union and territory of the former Russian Empire and amalgamate them into a single Russian state. Alexander Rutskoy, the Vice President of Russia from 1991–1993, asserted irredentist claims to Narva in Estonia, Crimea in Ukraine, and Ust-Kamenogorsk in Kazakhstan, among other territories.[2]

Before war broke out between Russia and Georgia in 2008, Aleksandr Dugin visited South Ossetia and predicted, "Our troops will occupy the Georgian capital Tbilisi, the entire country, and perhaps even Ukraine and the Crimean Peninsula, which is historically part of Russia, anyway."[3] Former South Ossetian president Eduard Kokoity is a Eurasianist and argues that South Ossetia never left the Russian Empire and should be part of Russia.[4]

Hungary

The Hungarian far-right party and movement, Jobbik, espouses a form of Hungarian nationalism that fosters kinship with other "Turanian" peoples, including the Turkic peoples of Asia.[5]

Romania

The political activist Silviu Brucan, was involved in shaping eurasianism as a geopolitical concept, with articles focused on Russian politics that were published in a monthly magazine called Sfera Politicii.[6]

Turkey

Since the late 1990s, Eurasianism has gained some following in Turkey among nationalist (ulusalcı (tr)) circles. The most prominent figure who is associated with Dugin is Doğu Perinçek, the leader of the Patriotic Party (Vatan Partisi).[7] Some analysts of modern Turkish politics have suggested that the ultra-nationalist and secular elite that are also affiliated with the members of the Turkish military, who have come under close scrutiny with the Ergenekon coup case, have close ideological and political ties to the Eurasianists.[8]

In literature

In the future time depicted in George Orwell's novel "Nineteen Eighty Four", the Soviet Union has mutated into Eurasia, one of the three superstates dominating the world.

Similarly, Robert Heinlein's story "Solution Unsatisfactory" depicts a future in which the Soviet Union would be transformed into "The Eurasian Union".

See also

References

- 1 2 Laruelle, Marlène "Histoire d'une usurpation intellectuelle: Gumilev, 'le dernier des eurasistes'? (analyse des oppositions entre L.N. Gumilev et P.N. Savickij" in Sergei Panarin (ed.) Eurasia: People & Myths, Moscow, Natalis Press, 1993 (Russian lang.)

- ↑ Chapman, Thomas; Roeder, Philip G. (November 2007). "Partition as a Solution to Wars of Nationalism: The Importance of Institutions". American Political Science Review. 101 (4): 680. doi:10.1017/s0003055407070438.

- ↑ "Road to War in Georgia: The Chronicle of a Caucasian Tragedy", Spiegel, August 25, 2008.

- ↑ Neo-Eurasianist Aleksandr Dugin on the Russia-Georgia Conflict, CACI Analyst, September 3, 2008.

- ↑ Evelyne Pieiller, "Hungary Looks to the Past for Its Future," Le Monde Diplomatique, English ed. November, 2016. http://mondediplo.com/2016/11/10hungary

- ↑ Brucan, Silviu. "Geopolitics and Strategy" (PDF). sferapoliticii.ro. Sfera Politicii. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ↑ Mehmet Ulusoy: "Rusya, Dugin ve‚ Türkiye’nin Avrasyacılık stratejisi" Aydınlık Dec. 5 2004, pp. 10-16

- ↑ Emre Uslu: Turkish military: a source of anti-Americanism in Turkey. Today's Zaman, July 31, 2011.

Sources

- The Mission of Russian Emigration, M.V. Nazarov. Moscow: Rodnik, 1994. ISBN 5-86231-172-6

- Russia Abroad: A comprehensive guide to Russian Emigration after 1917 also some Ustrialov's papers in the Library

- RUSSIA'S EASTERN OFFENSIVE: EURASIANISM VERSUS ATLANTICISM

- The criticism towards the West and the future of Russia-Eurasia

- Laruelle, Marlene, ed. (2015). Eurasianism and the European Far Right: Reshaping the Europe–Russia Relationship. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-1068-4.

- Stefan Wiederkehr, Die eurasische Bewegung. Wissenschaft und Politik in der russischen Emigration der Zwischenkriegszeit und im postsowjetischen Russland (Köln u.a., Böhlau 2007) (Beiträge zur Geschichte Osteuropas, 39).