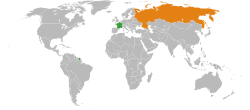

France–Russia relations

| |

France |

Russia |

|---|---|

France–Russia relations (French: Relations entre la France et la Russie, Russian: Российско-французские отношения, Rossiysko-frantsuzskiye otnosheniya) date back to the early modern period.

According to a 2017 Pew Global Attitudes Project survey, 36% of French people have a favorable view of Russia, with 62% expressing an unfavorable view.[1] A 2018 opinion poll published by the Russian Public Opinion Research Center shows that 81% of Russians have a favorable view of France, with 19% expressing a negative opinion.[2]

History

18th century

Franco-Russian diplomatic ties go back at least to 1702, when France had an ambassador (Jean-Casimir Baluze) in Moscow.[3] Following Russia's victory over Sweden in the Great Northern War of 1700 to 1721, the foundation of Saint Petersburg as the new Russian capital in 1712, and Peter the Great's declaration of the Russian Empire in 1721, Russia became a major force in Western European affairs for the first time. The geographical separation between France and Russia meant that their spheres of influence rarely overlapped. When involved in the same war, their troops rarely fought together as allies or directly against each other as enemies on the same battlefields. However, each state played a crucial role in the European balance of power. The two countries' armed forces fought on opposite sides in the 1733–1738 War of the Polish Succession and in the 1740-1748 War of the Austrian Succession; they were allies against Prussia during the Seven Years' War of 1756 to 1763.

19th century

Russia played a complex role in the Napoleonic wars. Russia fought against in the War of the Second Coalition. Once Napoleon Bonaparte (later Emperor Napoleon I) came to power in 1799, Russia remained hostile and fought in the Wars of the Third and Fourth Coalitions, which were victories for France and saw French power extend into Central Europe. This led to the establishment of a French-backed Polish state, the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807, which threatened Russia and caused tensions that led to the French invasion of Russia in 1812. This was major defeat for France and a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars, leading to Bonaparte's abdication and the Bourbon Restoration. Russia played a central role in defeating Napoleon in 1814. At the Vienna Congress of 1814-15, Russia played a major diplomatic role as a leader of the conservative, anti-revolutionary forces. This suited the Bourbon kings who again ruled France. Russia was a leader of the conservative Concert of Europe which sought to stifle revolution.

Russia was again hostile when the Revolutions of 1848 broke out across Europe, bringing Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte (later Emperor Napoleon III) to power in France. Napoleon III favoured a "policy of nationalities" (principe des nationalités) or support to national revolutions in multinational countries like Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, something fervently opposed by the Tsarist regime in Russia. France's challenges to Russia's influence led France to participate in the Crimean War, which saw French troops invade the Crimean peninsula. Imperial Russia's foreign policy was hostile to republican France in the 19th century and very pro-German. The First and Second Three Emperor's Leagues of the 1870s and 1880s-which brought together Germany, Austria and Russia-had as its stated purpose the preservation of the monarchical order in Europe against the France of the Third Republic. After the defeat in the Franco-German war of 1870-71, French elites concluded that France could never hope to defeat Germany on its own, and the way to defeat the Reich would be with the help of another great power.[4] Otto von Bismarck drew the same conclusion and worked hard to keep France diplomatically isolated.[5]

France was deeply split between the monarchists on one side, and the Republicans on the other. The Republicans at first seemed highly unlikely to welcome any military alliance with Russia. That large nation was poor and not industrialized; it was intensely religious and authoritarian, with no sense of democracy or freedom for its peoples. It oppressed Poland, and exiled, and even executed political liberals and radicals. At a time when French Republicans were rallying in the Dreyfus affair against anti-Semitism, Russia was the most notorious center in the world of anti-Semitic outrages, including multiple murderous large-scale pogroms against the Jews. On the other hand, France was increasingly frustrated by Bismarck's success in isolating it diplomatically. France had issues with Italy, which was allied with Germany and Austria-Hungary in the Triple Alliance. Paris made a few overtures to Berlin, but they were rebuffed, and after 1900 there was a threat of war between France and Germany over Germany's attempt to deny French expansion into Morocco. Great Britain was still in its “splendid isolation” mode and after a major agreement in 1890 with Germany, it seemed especially favorable toward Berlin. By 1892, Russia was the only opportunity for France to break out of its diplomatic isolation. Russia had been allied with Germany when Kaiser Wilhelm II dismissed Bismarck in 1890 and ended the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia in 1892. Russia was alone diplomatically and like France, it needed a military alliance to contain the threat of Germany’s strong army and military aggressiveness. The pope, angered by German anti-Catholicism, worked diplomatically to bring Paris and St. Petersburg together. Russia desperately needed money for the completion of railways and ports. The German government refused to allow its banks to lend money to Russia, but French banks did so eagerly. For example, it funded the essential trans-Siberian railway. Rejected by Germany, Russia cautiously began a policy of rapprochement with France starting in 1891 while the French for their part were very interested in the Russian offers of an alliance.[6]

In August 1891, France and Russia signed a "consultative pact" where both nations agreed to consult each other if another power were to threaten the peace of Europe. Negotiations were increasingly successful, and in early 1894 France and Russia agreed to the Franco-Russian Alliance, a military pledge to join together in war if Germany attacked either of them. The alliance was intended to deter Germany from going to war by presenting it with the threat of a two-front war; neither France or Russia could hope to defeat Germany on its own, but their combined power might do so. France had finally escaped its diplomatic isolation.[7][8] The alliance was secret until 1897, when the French government realized that secrecy was defeating its deterrent value. After France was humiliated by Britain in the Fashoda Incident of 1898, the French wanted the alliance to become an anti-British alliance. In 1900, the alliance was amended to name Great Britain as a threat and stipulated that should Britain attack France, Russia would invade India. The French provided a loan so that the Russians could start the construction of a railroad from Orenburg to Tashkent. Tashkent in its turn would be the base from which the Russians would invade Afghanistan as the prelude to invading India.[9]

20th century

In 1902, Japan formed a military alliance with Britain, which built up an Anglo-Japanese alliance. In response, Russia worked with France in order to renege on agreements to reduce troop strength in Manchuria. On March 16, 1902, a mutual pact was signed between France and Russia. Japan later fought Russia in the Russo-Japanese war. France remained neutral in this conflict.

In 1908-09 during the Bosnian crisis, France declined to support Russia against Austria and Germany . The lack of French interest in supporting Russia during the Bosnia crisis was the low point of Franco-Russian relations with the Emperor Nicholas II making no effort to hide his disgust at the lack of support from what was supposed to be his number one ally. Nicholas seriously considered abrogating the alliance with France, and was only stopped by the lack of an alternative.[10] Further linking France and Russia together was a common economic interests. Russia wished to industrialize, but lacked the capital to do so while the French were more than prepared to lend the necessary money to finance Russia's industrialisation. By 1913, French investors had invested 12 billion francs into Russian assets, making the French the largest investors in the Russian empire. The industrialisation of the Russian Empire was partially the result of a massive influx of French capital into the country.[11]

Since 1991

France's bilateral relations with the Soviet Union experienced dramatic ups and downs due to Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, and France's alliance in the NATO. Previous Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev made a visit to France in October 1985 in order to fix the strains in the Franco-Soviet relations. Nevertheless, France's bilateral activities continued with NATO, which furthermore strained the bilateral relations between France and the Soviet Union.

After the breakup of the USSR, bilateral relations between France and Russia were initially warm. On February 7, 1992 France signed a bilateral treaty, recognizing Russia as a successor of the USSR. As described by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the bilateral relations between France and Russia remain longstanding, and remain strong to this day.[12]

During the 2008 Georgia-Russia War, Sarkozy did not insist on territorial integrity of Georgia. Moreover, there were no French protests when Russia failed to obey Sarkozy's deal to withdraw from Georgia and recognizing governments in Georgia's territories.[13]

One of the major news has been the sale of Mistral class amphibious assault ships to Russia. The deal which was signed at 2010,[14] is the first major arms deal between Russia and the Western world since World War II.[15] The deal has been criticized for neglecting the security interests of Poland, the Baltic states, Ukraine, and Georgia.[13]

Before Syrian Civil War, Franco-Russian relations were generally improving. After years flailing behind Germany and Italy, France decided to copy them by emphasising the bilateral relationship. Ever since the financial crisis took hold, European powers have been forced to court emerging markets more and Moscow meanwhile wanted to diversify its own economy. President Hollande summed up the attitude towards what some said Putin's repressive array of new laws during his first official visit to Moscow in February 2013: "I do not have to judge, I do not have to evaluate".[16]

Since 2015: cooperation against ISIS

France and Russia were both attacked by the Middle-Eastern Islamist group ISIS. As a response, François Hollande and Vladimir Putin agreed on ordering their respective armed forces to "cooperate" with one another in the fight against the terrorist organization. The French President has called upon the international community to bring "together of all those who can realistically fight against this terrorist army in a large and unique coalition."[17] The French-Russian bombing cooperation is considered to be an "unprecedented" move, given that France is a member of NATO.[18]

The French press highlighted that ISIS is the first common enemy that France and Russia fight shoulder to shoulder since World War II.[19] A Russian newspaper recalled that "WWII had forced the Western World and the Soviet Union to overcome their ideological differences", wondering whether ISIS would be the "new Hitler".[20]

French intelligence services in Russia

In 1980 France's domestic intelligence service, the DST recruited KGB officer Vladimir Vetrov as a double agent.[21]

Russian intelligence services in France

During the Cold War, Russian active measures targeted French public opinion. Some indication of the success is given by polls that showed more French support to the Soviet Union than the United States.[22]

According to French counterintelligence sources in 2010, Russian espionage operations against France have reached levels not seen since the 1980s.[23]

Examples of operations

Examples of suspected or verified Soviet and Russian operations:

- Agence France-Presse - The Mitrokhin archive identified six agents and two confidential contacts.[24]

- Le Monde - The newspaper (codename VESTNIK, "messenger") was notable for spreading anti-American, pro-Soviet disinformation to the French population. The Mitrokhin archive contains two senior Le Monde journalists and several contributors.[24]

- La Tribune des Nations - Effectively KGB-run.[25]

- Various bogus biographies.[25]

- Infiltration of Gaullist movement: "More than any other political movement, Gaullism was swarming with agents of influence of the obliging KGB, whom we never succeeded in keeping away from de Gaulle"[26]

- Almost 15 million francs to De Gaulle's campaign, delivered by a businessman recruited by the KGB.[27]

- KGB hired people close to François Mitterrand.[28]

- Agents close to President Georges Pompidou were ordered to manipulate him with disinformation so he would become suspicious of the United States.[29]

- Pierre Charles Pathé - KGB codename PECHERIN (later MASON) run one of Moscow's disinformation networks for 20 years until French counterintelligence decided to arrest him during a financial transaction.

See also

References

- ↑ "Publics Worldwide Unfavorable Toward Putin, Russia". Pew Research Center. November 30, 2017.

- ↑ "RUSSIA AND FRANCE: THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE". Russian Public Opinion Research Center. May 28, 2018.

- ↑ "Jan Kazimierz Baluze, czyli Polak ambasadorem Francji w Rosji".

- ↑ Smith, Leonard; Audoin-Rouzeau, Steéphane, & Becker, Annette France and the Great War, 1914-1918, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003 page 11.

- ↑ Smith, Leonard; Audoin-Rouzeau, Steéphane, & Becker, Annette France the Great War, 1914-1918, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003 page 11.

- ↑ Leonard Smith, et al. France and the Great War, 1914-1918 (2003) pp 11-12.

- ↑ John B. Wolf, France 1814-1919: The rise of a Liberal-Democratic Society (1963)

- ↑ William L. Langer, The diplomacy of Imperialism: 1890–1902 (2nd ed. 1960), pp 3-66.

- ↑ A. J. P. Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848-1918 (1954) p. 398

- ↑ Tomaszewski, Fiona "Pomp, Circumstance, and Realpolitik: The Evolution of the Triple Entente of Russia, Great Britain, and France" pages 362-380 from Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 47#3 (1999) pp 369-70.

- ↑ Olga Crisp (1976). Studies in the Russian Economy before 1914. Springer. p. 161.

- ↑ French Ministry of foreign affairs - France and Russia

- 1 2 THE FOREIGN POLICY OF NICOLAS SARKOZY: The foreign policy of Nicolas Sarkozy: Not principles, opportunistic and amateurish. Marchel H. Van Herpen. February 2010

- ↑ "Russia to buy French warship by year end - federal agency". RIA Novosti. 21 April 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ↑ KRAMER, ANDREW (12 March 2010). "As Its Arms Makers Falter, Russia Buys Abroad". New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ↑ "How do you solve a problem like Russia?". the Guardian.

- ↑ Russia Open to Cooperation in Fight Against ISIS: French Foreign Minister, Newsweek

- ↑ Hollande in Moscow: A new era in Russian-French relations?, BBC News

- ↑ (in French) Syrie : la France et la Russie s'allient contre Daech, Le Parisien

- ↑ (in French) Daech, premier ennemi que la France et la Russie pourraient combattre ensemble depuis 1945, Le Huffington Post

- ↑ "Farewell — The Greatest Spy Story of the Twentieth Century by Sergei Kostin and Eric Raynaud". Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- ↑ Andrew, Christopher, Vasili Mitrokhin (2000). The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-00312-5. p. 166

- ↑ French secret service fear Russian cathedral a spying front. The Telegraph. 2010-05-28

- 1 2 Andrew, Christopher, Vasili Mitrokhin (2000). The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-00312-5. p. 169-171

- 1 2 The Sword and the Shield (2000) p. 461-462

- ↑ The Sword and the Shield (2000) p. 463

- ↑ The Sword and the Shield (2000) p. 463

- ↑ The Sword and the Shield (2000) p. 464

- ↑ The Sword and the Shield (2000) p. 467-468

Further reading

- Adams, Michael. Napoleon and Russia (2006)

- Andrew, Christopher. Théophile Délcassé and the Making of the Entente Cordiale, 1898–1905 (1968).

- Bovykin, V.I. “The Franco-Russian Alliance.” History 64 (1979), pp. 20–35.

- Carley, Michael Jabara. "Prelude to Defeat: Franco-Soviet Relations, 1919-39." Historical Reflections/Réflexions Historiques (1996): 159-188. in JSTOR

- Carley, Michael Jabara. "Episodes from the Early Cold War: Franco-Soviet Relations, 1917–1927." Europe-Asia Studies 52.7 (2000): 1275-1305.

- Caroll, E.M. French Public Opinion and Foreign Affairs, 1870–1914 (1931).

- Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe went to war in 1914 (2012), pp. 124–35, 190-96, 293-313, 438-42, 498-505.

- Fay, Sidney Bradshaw. The Origins of the World War (2nd ed. 1934) vol 1 pp 105–24, 312-42, vol 2 pp 277–86, 443-46.

- Hamel, Catherine. La commémoration de l’alliance franco-russe : La création d’une culture matérielle populaire, 1890-1914 (French) (MA thesis, Concordia University, 2016) ; online

- Jelavich, Barbara. Century of Russian Foreign Policy, 1814–1914 (1964.)

- Kaplan, Herbert H. Russia and the outbreak of the Seven Years' War (1968) on 1750s.

- Keiger, J.F.V. France and the World since 1870 (2001)

- Kennan, George Frost. The fateful alliance: France, Russia, and the coming of the First World War (1984) online free to borrow

- Kennan, George F. The decline of Bismarck's European order: Franco-Russian relations, 1875-1890 (1979).

- Langer, William F. The Franco-Russian Alliance, 1890-1894 (1930)

- Langer, William F. The Diplomacy of Imperialism: 1890-1902 (1950) pp 3–66.

- Lieven, Dominic. Russia against Napoleon: the battle for Europe, 1807 to 1814 (2009).

- Michon, Georges. The Franco-Russian Alliance (1969).

- Ragsdale, Hugh, and Ponomarev, V.N., eds. Imperial Russian Foreign Policy (1993).

- Saul, Norman E. Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Foreign Policy (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014).

- Schmitt, B.E. The Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente (1947).

- Siegel, Jennifer. For Peace and Money: French and British Finance in the Service of Tsars and Commissars (Oxford UP, 2014) on First World War loans.

- Sontag, Raymond James. European diplomatic history, 1871-1932 (1933), pp 29–58.

- Taylor, A.J.P. The struggle for mastery in Europe, 1848-1918 (1954) pp 325–45.

- Tomaszewski, Fiona. "Pomp, Circumstance, and Realpolitik: The Evolution of the Triple Entente of Russia, Great Britain, and France." Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas vol. 3 (1999): 362-380. in JSTOR, in English

- Tomaszewski, Fiona K. A Great Russia: Russia and the Triple Entente, 1905-1914 (Greenwood, 2002). Online

- Wall, Irwin. "France in the Cold War" Journal of European Studies (2008) 38#2 pp 121–139.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Relations of France and Russia. |