Peptide

Peptides (from Gr.: πεπτός, peptós "digested"; derived from πέσσειν, péssein "to digest") are short chains of amino acid monomers linked by peptide (amide) bonds.

The covalent chemical bonds are formed when the carboxyl group of one amino acid reacts with the amino group of another. The shortest peptides are dipeptides, consisting of 2 amino acids joined by a single peptide bond, followed by tripeptides, tetrapeptides, etc. A polypeptide is a long, continuous, and unbranched peptide chain. Hence, peptides fall under the broad chemical classes of biological oligomers and polymers, alongside nucleic acids, oligosaccharides and polysaccharides, etc.

Peptides are distinguished from proteins on the basis of size, and as an arbitrary benchmark can be understood to contain approximately 50 or fewer amino acids.[1][2] Proteins consist of one or more polypeptides arranged in a biologically functional way, often bound to ligands such as coenzymes and cofactors, or to another protein or other macromolecule (DNA, RNA, etc.), or to complex macromolecular assemblies.[3] Finally, while aspects of the lab techniques applied to peptides versus polypeptides and proteins differ (e.g., the specifics of electrophoresis, chromatography, etc.), the size boundaries that distinguish peptides from polypeptides and proteins are not absolute: long peptides such as amyloid beta have been referred to as proteins, and smaller proteins like insulin have been considered peptides.

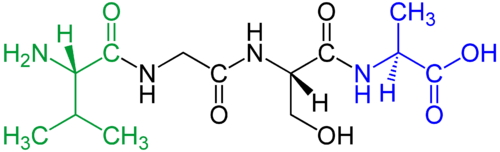

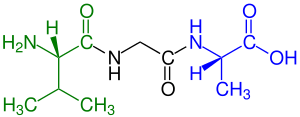

Amino acids that have been incorporated into peptides are termed "residues" due to the release of either a hydrogen ion from the amine end or a hydroxyl ion (OH−) from the carboxyl (COOH) end, or both, as a water molecule is released during formation of each amide bond.[4] All peptides except cyclic peptides have an N-terminal and C-terminal residue at the end of the peptide (as shown for the tetrapeptide in the image).

Peptide classes

Many kinds of peptides are known. They have been classified or categorized according to their sources and function. According to the Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides, some groups of peptides include plant peptides, bacterial/antibiotic peptides, fungal peptides, invertebrate peptides, amphibian/skin peptides, venom peptides, cancer/anticancer peptides, vaccine peptides , immune/inflammatory peptides, brain peptides, endocrine peptides, ingestive peptides, gastrointestinal peptides, cardiovascular peptides, renal peptides, respiratory peptides, opiate peptides, neurotrophic peptides, and blood–brain peptides.[5]

Some ribosomal peptides are subject to proteolysis. These function, typically in higher organisms, as hormones and signaling molecules. Some organisms produce peptides as antibiotics, such as microcins.[6]

Peptides frequently have posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation, hydroxylation, sulfonation, palmitoylation, glycosylation and disulfide formation. In general, peptides are linear, although lariat structures have been observed.[7] More exotic manipulations do occur, such as racemization of L-amino acids to D-amino acids in platypus venom.[8]

Nonribosomal peptides are assembled by enzymes, not the ribosome. A common non-ribosomal peptide is glutathione, a component of the antioxidant defenses of most aerobic organisms.[9] Other nonribosomal peptides are most common in unicellular organisms, plants, and fungi and are synthesized by modular enzyme complexes called nonribosomal peptide synthetases.[10]

These complexes are often laid out in a similar fashion, and they can contain many different modules to perform a diverse set of chemical manipulations on the developing product.[11] These peptides are often cyclic and can have highly complex cyclic structures, although linear nonribosomal peptides are also common. Since the system is closely related to the machinery for building fatty acids and polyketides, hybrid compounds are often found. The presence of oxazoles or thiazoles often indicates that the compound was synthesized in this fashion.[12]

Peptide fragments refer to fragments of proteins that are used to identify or quantify the source protein.[13] Often these are the products of enzymatic degradation performed in the laboratory on a controlled sample, but can also be forensic or paleontological samples that have been degraded by natural effects.[14][15]

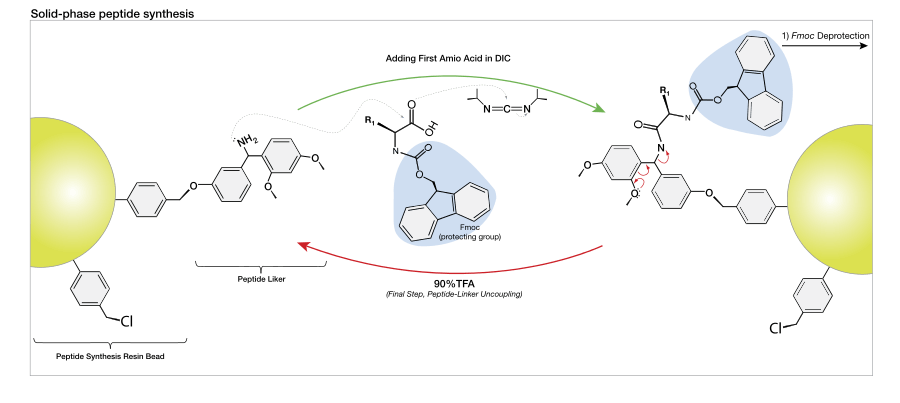

Peptide synthesis

Peptides in molecular biology

Peptides received prominence in molecular biology for several reasons. The first is that peptides allow the creation of peptide antibodies in animals without the need of purifying the protein of interest.[16] This involves synthesizing antigenic peptides of sections of the protein of interest. These will then be used to make antibodies in a rabbit or mouse against the protein.

Another reason is that peptides have become instrumental in mass spectrometry, allowing the identification of proteins of interest based on peptide masses and sequence.

Peptides have recently been used in the study of protein structure and function. For example, synthetic peptides can be used as probes to see where protein-peptide interactions occur- see the page on Protein tags.

Inhibitory peptides are also used in clinical research to examine the effects of peptides on the inhibition of cancer proteins and other diseases.[17] For example, one of the most promising application is through peptides that target LHRH.[18] These particular peptides act as an agonist, meaning that they bind to a cell in a way that regulates LHRH receptors. The process of inhibiting the cell receptors suggests that peptides could be beneficial in treating prostate cancer. However, additional investigations and experiments are required before the cancer-fighting attributes, exhibited by peptides, can be considered definitive.[19]

Well-known peptide families

The peptide families in this section are ribosomal peptides, usually with hormonal activity. All of these peptides are synthesized by cells as longer "propeptides" or "proproteins" and truncated prior to exiting the cell. They are released into the bloodstream where they perform their signaling functions.

Antimicrobial peptides

- Magainin family

- Cecropin family

- Cathelicidin family

- Defensin family

Tachykinin peptides

Vasoactive intestinal peptides

Pancreatic polypeptide-related peptides

Opioid peptides

- Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) peptides

- Enkephalin pentapeptides

- Prodynorphin peptides

Calcitonin peptides

Other peptides

- B-type Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) - produced in myocardium & useful in medical diagnosis

- Lactotripeptides - Lactotripeptides might reduce blood pressure,[20][21][22] although the evidence is mixed.[23]

- Peptidic components from traditional Chinese medicine Colla Corii Asini in hematopoiesis.[24]

Terminology

Length

Several terms related to peptides have no strict length definitions, and there is often overlap in their usage.

- A polypeptide is a single linear chain of many amino acids (any length), held together by amide bonds.

- A protein consists of one or more polypeptides (more than about 50 amino acids long).

- An oligopeptide consists of only a few amino acids (between two and twenty).

Number of amino acids

Peptides of defined length are named using IUPAC numerical multiplier prefixes.

- A monopeptide has one amino acid.

- A dipeptide has two amino acids.

- A tripeptide has three amino acids.

- A tetrapeptide has four amino acids.

- A pentapeptide has five amino acids.

- A hexapeptide has six amino acids.

- A heptapeptide has seven amino acids.

- An octapeptide has eight amino acids (e.g., angiotensin II).

- A nonapeptide has nine amino acids (e.g., oxytocin).

- A decapeptide has ten amino acids (e.g., gonadotropin-releasing hormone & angiotensin I).

Function

- A neuropeptide is a peptide that is active in association with neural tissue.

- A lipopeptide is a peptide that has a lipid connected to it, and pepducins are lipopeptides that interact with GPCRs.

- A peptide hormone is a peptide that acts as a hormone.

- A proteose is a mixture of peptides produced by the hydrolysis of proteins. The term is somewhat archaic.

- A peptidergic agent (or drug) is a chemical which functions to directly modulate the peptide systems in the body or brain. An example is opioidergics, which are neuropeptidergics.

Doping in sports

The term peptide has been used to mean secretagogue peptides and peptide hormones in sports doping matters: secretagogue peptides are classified as Schedule 2 (S2) prohibited substances on the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) Prohibited List, and are therefore prohibited for use by professional athletes both in and out of competition. Such secretagogue peptides have been on the WADA prohibited substances list since at least 2008. The Australian Crime Commission cited the alleged misuse of secretagogue peptides in Australian sport including growth hormone releasing peptides CJC-1295, GHRP-6, and GHSR (gene) hexarelin. There is ongoing controversy on the legality of using secretagogue peptides in sports.[25]

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Peptide |

- Argireline

- Beefy meaty peptide

- Bis-peptide

- CLE peptide

- Epidermal growth factor

- Journal of Peptide Science

- Lactotripeptides

- Multifunctional peptides

- Neuropeptides

- Palmitoyl pentapeptide-4

- Pancreatic hormone

- Peptide Spectral Library

- Peptide synthesis

- Peptidomimetics (such as peptoids and β-peptides) to peptides, but with different properties.

- Protein tag, describing addition of peptide sequences to enable protein isolation or detection

- Replikins

- Ribosome

- Translation

References

- ↑ IUPAC. Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book"). Compiled by A. D. McNaught and A. Wilkinson. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford (1997). XML on-line corrected version: http://goldbook.iupac.org (2006-) created by M. Nic, J. Jirat, B. Kosata; updates compiled by A. Jenkins. ISBN 0-9678550-9-8. doi:10.1351/goldbook.P04898.

- ↑ "What are peptides". Zealand Pharma A/S. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14.

- ↑ Ardejani, Maziar S.; Orner, Brendan P. (2013-05-03). "Obey the Peptide Assembly Rules". Science. 340 (6132): 561–562. Bibcode:2013Sci...340..561A. doi:10.1126/science.1237708. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 23641105.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "amino-acid residue in a polypeptide".

- ↑ Abba J. Kastin, ed. (2013). Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-0-12-385095-9.

- ↑ Duquesne S, Destoumieux-Garzón D, Peduzzi J, Rebuffat S; Destoumieux-Garzón; Peduzzi; Rebuffat (August 2007). "Microcins, gene-encoded antibacterial peptides from enterobacteria". Natural Product Reports. 24 (4): 708–34. doi:10.1039/b516237h. PMID 17653356.

- ↑ Pons M, Feliz M, Antònia Molins M, Giralt E; Feliz; Antònia Molins; Giralt (May 1991). "Conformational analysis of bacitracin A, a naturally occurring lariat". Biopolymers. 31 (6): 605–12. doi:10.1002/bip.360310604. PMID 1932561.

- ↑ Torres AM, Menz I, Alewood PF, et al. (July 2002). "D-Amino acid residue in the C-type natriuretic peptide from the venom of the mammal, Ornithorhynchus anatinus, the Australian platypus". FEBS Letters. 524 (1–3): 172–6. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03050-8. PMID 12135762.

- ↑ Meister A, Anderson ME; Anderson (1983). "Glutathione". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 52 (1): 711–60. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. PMID 6137189.

- ↑ Hahn M, Stachelhaus T; Stachelhaus (November 2004). "Selective interaction between nonribosomal peptide synthetases is facilitated by short communication-mediating domains". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (44): 15585–90. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10115585H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0404932101. PMC 524835. PMID 15498872.

- ↑ Finking R, Marahiel MA; Marahiel (2004). "Biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides1". Annual Review of Microbiology. 58 (1): 453–88. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123615. PMID 15487945.

- ↑ Du L, Shen B; Shen (March 2001). "Biosynthesis of hybrid peptide-polyketide natural products". Current Opinion in Drug Discovery & Development. 4 (2): 215–28. PMID 11378961.

- ↑ Hummel J, Niemann M, Wienkoop S; et al. (2007). "ProMEX: a mass spectral reference database for proteins and protein phosphorylation sites". BMC Bioinformatics. 8 (1): 216. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-8-216. PMC 1920535. PMID 17587460.

- ↑ Webster J, Oxley D; Oxley (2005). "Peptide mass fingerprinting: protein identification using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry". Methods in Molecular Biology. Methods in Molecular Biology™. 310: 227–40. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-948-6_16. ISBN 978-1-58829-399-2. PMID 16350956.

- ↑ Marquet P, Lachâtre G; Lachâtre (October 1999). "Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry: potential in forensic and clinical toxicology". Journal of Chromatography B. 733 (1–2): 93–118. doi:10.1016/S0378-4347(99)00147-4. PMID 10572976.

- ↑ Bulinski JC (1986). "Peptide antibodies: new tools for cell biology". International Review of Cytology. International Review of Cytology. 103: 281–302. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)60838-4. ISBN 9780123645036. PMID 2427468.

- ↑ Herce, Henry D.; Deng, Wen; Helma, Jonas; Leonhardt, Heinrich; Cardoso, M. Cristina (24 October 2013). "Visualization and targeted disruption of protein interactions in living cells". Nature Communications. 4. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4E2660H. doi:10.1038/ncomms3660. PMC 3826628. PMID 24154492.

- ↑ "Hormone (androgen deprivation) therapy for prostate cancer". cancer.org. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ↑ Kumar, Ravi; Barqawi, A; Crawford, ED (2005). "Adverse Events Associated with Hormonal Therapy for Prostate Cancer". Reviews in Urology. 7 (5): 37–43. PMC 1477613. PMID 16985883.

- ↑ Boelsma E, Kloek J; Kloek (March 2009). "Lactotripeptides and antihypertensive effects: a critical review". The British Journal of Nutrition. 101 (6): 776–86. doi:10.1017/S0007114508137722. PMID 19061526.

- ↑ Xu JY, Qin LQ, Wang PY, Li W, Chang C; Qin; Wang; Li; Chang (October 2008). "Effect of milk tripeptides on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Nutrition. 24 (10): 933–40. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2008.04.004. PMID 18562172.

- ↑ Pripp AH (2008). "Effect of peptides derived from food proteins on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Food & Nutrition Research. 52: 10.3402/fnr.v52i0.1641. doi:10.3402/fnr.v52i0.1641. PMC 2596738. PMID 19109662.

- ↑ Engberink MF, Schouten EG, Kok FJ, van Mierlo LA, Brouwer IA, Geleijnse JM; Schouten; Kok; Van Mierlo; Brouwer; Geleijnse (February 2008). "Lactotripeptides show no effect on human blood pressure: results from a double-blind randomized controlled trial". Hypertension. 51 (2): 399–405. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098988. PMID 18086944.

- ↑ Wu, Hongzhong; Ren, Chunyan; Yang, Fang; Qin, Yufeng; Zhang, Yuanxing; Liu, Jianwen (April 2016). "Extraction and identification of collagen-derived peptides with hematopoietic activity from Colla Corii Asini". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 182: 129–136. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2016.02.019.

- ↑ Koh, Benjamin. "We need an advocate against ASADA's power in doping control".