Native Indonesians

.jpg) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

c. 210 million (Worldwide; 2006 estimate)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| 21,700,000[2] | |

| 850,000[3] | |

| 500,000 | |

| 102,100[4] | |

| 101,270[5][6] | |

| 86,196[7] | |

| 75,000[8] | |

| 10,000[9] | |

| Languages | |

|

Indonesian languages (Indonesian, Malay, Javanese, Sundanese, Batak, Madurese, etc) | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (predominantly Sunnis, Shias and others[10]), Christianity (Protestantism and Roman Catholicism), Hindu Dharma, Buddhism, Animism, Shamanism, Sunda Wiwitan, Kaharingan, Parmalim, Kejawen, Naurus, Aluk' To Dolo, etc. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Austronesians, Mongoloids, Polynesians, Papuans, Negritos, Melanesians, other Indonesians | |

|

a The figure in Malaysia merely assert those who holds an Indonesian citizenship, the figure does not include Malaysians who have some Indonesian ancestry which potentially double or triple of figure, due to the constant migration since millennia ago. | |

Native Indonesians, also Pribumi (literally "first on the soil") is a term used to distinguish Indonesians whose ancestral roots lie mainly in the archipelago from Indonesians of known (partial) foreign descent, especially Chinese Indonesians and Indo-Europeans (Eurasians). In practice, the term is seldom used in relation to Indonesians of Melanesian descent, although it does not exclude them. The term "native Indonesians" should not be confused with the more generic term Indonesians or Indonesian citizens. The term putra daerah ("son of the region") refers to a person who is indigenous to a specific locality or region. The term bumiputra is sometimes used in Indonesia with the same meaning as pribumi, but is more commonly used in Malaysia, where it has a slightly different meaning.[11]

Etymology and historical context

The term "pribumi" was coined after Indonesian independence as a respectful replacement for the Dutch colonial term "inlander" (normally translated as "native" and seen as derogatory).[12] It derives from Sanskrit terms pri (before) and bhumi (earth).

Following independence, the term was normally used to distinguish indigenous Indonesians from citizens of foreign descent (especially Chinese Indonesians). Common usage distinguished between "pri" and "non-pri".[13] In 1998, the Indonesian government of President B.J. Habibie instructed that neither term should be used, on the grounds that they promoted ethnic discrimination.[14][15]

In ancient Java, the ideas of native versus foreign identities are usually confined into ethno-cultural and language boundaries, as the ideas of Javanese identity being developed. The Kaladi inscription (c. 909 CE), mentioned Kmir (Khmer people of Khmer kingdom) together with Campa (Champa) and Rman (Mon) as foreigners from mainland Southeast Asia that frequently came to Java to trade.[16] The Anjukladang inscription (c. 937 CE) mentioned about infiltration attack from Malayu (which refer to a Srivijayan attack). In this inscription, the ideas of native Javanese is contrasted to its "foreign nemesis", the Malays of Sumatra.

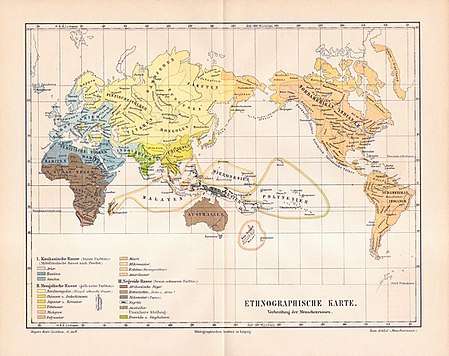

The ethnic composition in the archipelago grew to be more complex with the arrival of the people of foreign origin. Following the adoption of Hinduism, the Southern Indians called by natives as Keling began to arrive in archipelago in the early first millennia, and followed suit by fellow Indians when Tamils began to settles in several ports of Sumatra after the decline of Srivijaya circa 11th century. Also the arrivals of Chinese traders and settlers which intensify since Majapahit era, through the arrival of Zheng He's treasure fleet to Indonesia circa early 15th century. Around the same time, Muslim traders from India and Arabia also began to settle in the region. Caucasian white European arrived when Portuguese began to ruled and settle in Portuguese Malacca in 1511. Thus the ideas of racial identity to describe the differences between the native of the archipelago in contrast to the neighboring Asian foreigners and European white began to take root during early stages of European colonialism in Indonesia circa 16th to 17th century.

By 17th century, the Dutch East India Company began to get involved intensively in the archipelago, especially in Java, Moluccas and Sumatra. By the 19th century, the term pribumi is translated from inlander in Dutch, the term was first coined by the Dutch colonial administration to lump diverse groups of local inhabitants of Indonesia's archipelago, mostly for social discrimination purposes.

During the colonial period, the Dutch administration instilled a regime of three-level racial separation:

- The first class race being Europeans colonials

- The second class race being those of partial European ancestry as well as Foreign Orientals (Vreemde Oosterlingen) which includes Chinese, Arabs, and Indians

- The third class race being the natives (Inlanders), including Javanese, Malays, Dayaks, Papuans and Moluccans.

The colonial system was similar to the casta system in Hispanic America, or the South African apartheid system, which prohibited inter-racial neighborhoods (wet van wijkenstelsel) and inter-racial interactions were limited by passenstelsel laws.[1]

The outbreak of the World War II saw the fall of colonial state of Dutch East Indies. During Japanese occupation, the Dutch colonials were put into the lowest class of social strata. Native blood was the only thing that could free Indos (mixed Eurasian ancenstry) from being put into concentration camps.[17] The following Indonesian Revolution (1945-1949) saw the rise of Indonesian Republic, subsequently the revolution has brought a drastic social changes. The Dutch colonials and the Indos are suspiciously considered by republicans as Dutch loyalist, thus they are not a desired element in the newly established republic. By 1950s, large numbers of Dutch colonials and Indos were being repatriated to the Netherlands.

After the revolution, the natives majority has gained the political, social and economic power previously reserved only for Dutch colonials. In post colonial Indonesia, the Chinese Indonesians are the most significant minority group that being categorized as non-pribumi (non native).

Today, Indonesian dictionary describes pribumi as penghuni asli which translated into "original, native or indigenous inhabitant".[18]

Background

Pribumi make up about 95% of the Indonesian population.[1] Using Indonesia’s population estimate in 2006, this translates to about 230 million people. As an umbrella of similar cultural heritage among various ethnic groups in Indonesia, Pribumi culture plays a significant role in shaping the country’s socioeconomic circumstance.

The United States Library of Congress Country Study of Indonesia defines Pribumi as:

Literally, an indigene, or native. In the colonial era, the great majority of the population of the archipelago came to regard themselves as indigenous, in contrast to the non-indigenous Dutch and Chinese (and, to a degree, Arab) communities. After independence the distinction persisted, expressed as a dichotomy between elements that were pribumi and those that were not. The distinction has had significant implications for economic development policy

— Indonesia: A Country Study, Glossary[19]

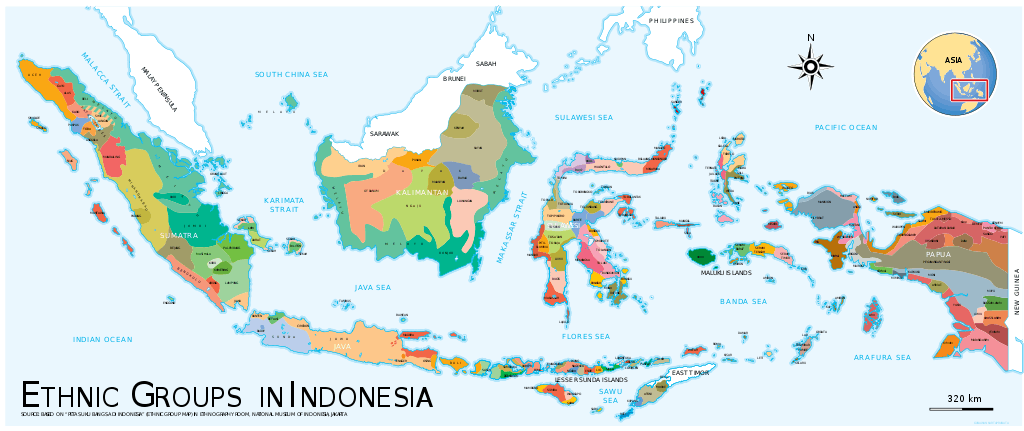

There are over 300 ethnic groups in Indonesia.[20] 200 of those are of Native Indonesian ancestry.

The largest ethnic group in Indonesia are the Javanese people who make up 41% of the total population. The Javanese are concentrated on the island of Java but millions have migrated to other islands throughout the archipelago.[21] The Sundanese, Malay, and Madurese are the next largest groups in the country.[21] Many ethnic groups, particularly in Kalimantan and the province of Papua, have only hundreds of members. Most of the local languages belong to the Austronesian language family, although a significant number, particularly in Papua, speak Papuan languages.

The division and classification of ethnic groups in Indonesia is not rigid and in some cases are unclear as the result of migrations, along with cultural and linguistic influences; for example some may agree that the Bantenese and Cirebonese belong to different ethnic groups with their own distinct dialect, however others might consider them to be Javanese sub-ethnicities, as members of the larger Javanese people. The same considerations may apply to the Baduy people who share so many similarities with the Sundanese people that they can be considered as belonging to the same ethnic group. The clearest example of hybrid ethnicity are the Betawi people, the result of a mixture of different native ethnicities that have merged with people of Arab, Chinese and Indian origins since the era of colonial Batavia (Jakarta).

The proportional populations of Native Indonesians according to the (2009 census) is as follows:

| Ethnic groups | Population (million) | Percentage | Main Regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Javanese | 95.217[22] | 40.2[22] | Central Java, Yogyakarta, East Java, Lampung, Jakarta[22] |

| Sundanese | 31.765 | 15.4 | West Java, Banten, Lampung |

| Malay | 8.789 | 4.1 | Sumatra eastern coast, West Kalimantan |

| Madurese | 6.807 | 3.3 | Madura island, East Java |

| Batak | 6.188 | 3.0 | North Sumatra |

| Bugis | 6.000 | 2.9 | South Sulawesi, East Kalimantan |

| Minangkabau | 5.569 | 2.7 | West Sumatra, Riau |

| Betawi | 5.157 | 2.5 | Jakarta, Banten, West Java |

| Banjarese | 4.800 | 2.3 | South Kalimantan, East Kalimantan |

| Bantenese | 4.331 | 2.1 | Banten, West Java |

| Acehnese | 4.000 | 1.9 | Aceh |

| Balinese | 3.094 | 1.5 | Bali |

| Dayak | 3.009 | 1.5 | North Kalimantan, West Kalimantan, Central Kalimantan |

| Sasak | 3.000 | 1.4 | West Nusa Tenggara |

| Makassarese | 2.063 | 1.0 | South Sulawesi |

| Cirebonese | 1.856 | 0.9 | West Java, Central Java |

Physical characteristics

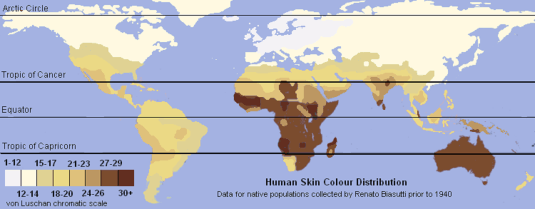

The skin color of native Indonesians ranges from fair skin with yellowish undertone to light brown to very dark brown or black skin color. Archaeologist Peter Bellwood claims that the "vast majority" of people in Indonesia and Malaysia, the region he calls the "clinal Mongoloid-Australoid zone", are "Southern Mongoloids" but have a "high degree" of Australoid admixture.[23]

Sawo matang (lit. "ripe sapodilla") usually refers to the skin colour of the Pribumis in Indonesia which connotes "mid light to dark tone brown" especially for those who live in Java, Bali, Sumatra, etc. For other places like in Borneo, Sulawesi, and eastern parts of Indonesia, native people tend to have darker skin colour who actually come from the east of Indonesia and for those who live in high altitude areas and highlands tend to have lighter skin colour like people from Sundanese, Manado, Tomohon, Dayak, etc. For islandic people, they tend to have dark skin colour which all of the physical characteristics depend on the geographical areas they inhabit.

Genetic research

Most Native Indonesians are genetically close to Asians while the more eastern one goes the more people show Melanesian affinity. Geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza claims that there is a genetic division between East and Southeast Asians.[24] In a similar manner, Zhou Jixu agrees that there is a physical difference between these two populations.[25] Other geneticists have found evidence for four separate populations, carrying distinct sets of non-recombining Y chromosome lineages, within the traditional Mongoloid category: North Asians, Han Chinese, Japanese and Southeast Asians.[26] The complexity of genetic data has led to doubt about the usefulness of the concept of a Mongoloid race itself, since distinctive East Asian features may represent separate lineages and arise from environmental adaptations or retention of common proto-Eurasian ancestral characteristics.[27]

Smaller groups

The regions of Indonesia have some of their indigenous ethnic groups. Due to migration within Indonesia (as part of government transmigration programs or otherwise), there are significant populations of ethnic groups who reside outside of their traditional regions.

- Java: Javanese, Sundanese, Bantenese, Betawi, Tengger, Osing, Badui

- Madura: Madurese

- Sumatra: Malays, Batak, Minangkabau, Acehnese, Lampung, Kubu

- Kalimantan: Malays, Dayak, Banjar

- Sulawesi: Makassarese, Buginese, Mandar, Minahasa, Buton, Gorontalo, Toraja, Bajau, Mongondow People, Buroko People, Bolango Tribe

- Lesser Sunda Islands: Balinese, Sasak

- The Moluccas: Nuaulu, Manusela, Wemale

- Papua: Dani, Bauzi, Asmat

Pribumi worldwide

Malaysia

Malaysia shares a border with Indonesia and both countries share many aspects of their culture, including mutually intelligible national languages. Populations have long moved between the areas which make up the modern-day states. Many people from Java, Kalimantan, Sumatra, and Sulawesi, which are located in modern-day Indonesia, migrated and settled to the Malay Peninsula and some to the Malaysian Borneo since time immemorial. These earlier populations have mostly effectively or partially assimilated with the larger Malaysian-Malay community due to religious, social and cultural similarities. Currently, it is also estimated that there are around 2 million Indonesian citizens in Malaysia at any given time, ranging from all types of background with a significant majority of them consisting of labour migrants, with a considerable number of professionals and students.

Saudi Arabia

Indonesian pilgrims have long lived in Hejaz, a region along the west coast of Saudi Arabia. Among them was Ahmad Khatib, who served as the Imam of the Shafi'i school of law at the mosque known as Masjidil Haram, Mecca.[28] Today, most of Indonesians in Saudi Arabia are female domestic workers, with a minority of other types of labour migrants and students. Most of the santri extension studied in Saudi, as well as Al Azhar University in Cairo.

United States

In the United States, most Indonesians are students and professionals. Boston University, University of California and Harvard University are some of the favorite schools for Indonesian people. In the Silicon Valley region of Northern California, there are many Indonesian-American engineers working in the high-tech industry.

Singapore

The Malays in Singapore (Malay: Orang Melayu Singapura) make up about 14% of the country's population. Most of them came from what we know today as Indonesia and southern Malaysia. In the 19th century, Singapore was part of Johor-Riau Sultanate. Many Indonesian people, mainly Bugi and Minangkabau settled in Singapore. From 1886 till 1890, as many as 21,000 Javanese became bonded labourers with the Singapore Chinese Protectorate, an organisation formed by the British in 1877 to monitor the Chinese population. They performed manual labour in the rubber plantations. After their bond ended, they continued to open up the land and stayed on in Johore. Famous Singaporeans of Indonesian descent are the first president of Singapore Yusof bin Ishak, and Zubir Said who composed the national anthem of Singapore Majulah Singapura.

The Netherlands

Indonesia was the colony of the Netherlands. Early 20th century, many Indonesian students studied in the Netherlands. Most of them lived in Leiden and were active in the Indonesian Vereeniging. After the Indonesian National Revolution, many Moluccans migrated to the Netherlands. Most of them were ex KNIL army. In this way around 12,500 persons were settled in the Netherlands.

Australia

Before Dutch and British sailors arrived in Australia, the Indonesians from Southern Sulawesi explored Australia northern coast. Each year, Bugi sailors would sail down on the northwestern monsoon in their wooden pinisi. They would stay in Australia for several months to trade and take tripang (dried sea cucumber) before returning to Makassar on the dry season offshore winds. These trading voyages continued until 1907. Furthermore, the Cocos Malays are descendants of native Indonesians were brought by the Clunies-Ross family to work in the copra industry in the 19th century.

Suriname

The Indonesian people, mainly Javanese, make up 15% of the population Suriname. In the 19th century, the Dutch sent the Javanese to Suriname as contract workers in plantations. The most famous person of Indonesian descent is Paul Somohardjo as the speaker of the National Assembly of Suriname.[29]

Japan

Hong Kong

South Korea

United Arab Emirates

Philippines

Like its other neighbors Malaysia and Singapore, Indonesia also shares a close and important history with the Philippines, as the two countries underwent migrations and back-migrations in their ancient histories. The southern parts of the Philippines were under the jurisprudence of the Majapahit Empire, the Laguna Copperplate Inscription also records interactions between the native Tagalog kingdoms in present-day Manila and that of the Kingdom of Medang. The eastern parts of North Kalimantan were part of the historical Sultanate of Sulu. According to Visayan legend, the Rajahnate of Cebu was found by a Sumatran prince by the name of Sri Lumay. Rajah Baguinda was a Minangkabau prince who migrated to the Sulu Archipelago. In the 1600s, during the colonial era, Spanish soldiers deported the Sultan of Ternate and his family to Manila, after conquering and capturing the Ternate Sultanate.

Today, Indonesians in the Philippines number anywhere from 43,871 to 101,720. They mostly reside in the island of Mindanao, in the Muslim parts with a noticeable community in Davao City that has an international school for the overseas community. They tend to be protective of their separate ethnic identity. Most are Muslims, while many others are also Christian - who, come from Minahasan-speaking ancestry.

Canada

Traditional performing arts

Music

Indonesia is home to various styles of music, with those from the islands of Java, Sumatra and Bali being frequently recorded. The traditional music of west, central, East Java and Bali is the gamelan.

Dangdut is a very popular music genre among the "Pribumis" across Indonesia. Kroncong is also a musical genre that uses guitars and ukuleles as the main musical instruments. This genre had its roots in Portugal and was introduced by Portuguese traders in the fifteenth century. There is a traditional Keroncong Tugu music group in North Jakarta and other traditional Keroncong music groups in Maluku, with strong Portuguese influences. This music genre was popular in the first half of the twentieth century; a contemporary form of Kroncong is called Pop Kroncong.

Angklung musical orchestra, native of West Java, received international recognition as UNESCO has listed the traditional West Java musical instrument made from bamboo in the list of intangible cultural heritage.[30][31]

The soft Sasando music from the province of East Nusa Tenggara in West Timor is completely different. Sasando uses an instrument made from a split leaf of the Lontar palm (Borassus flabellifer), which bears some resemblance to a harp.

Dance

Indonesian dance reflects the diversity of culture from ethnic groups that composed the nation of Indonesia. Austronesian roots and Melanesian tribal dance forms are visible, and influences ranging from neighboring Asian countries; such as India, China, and Middle East to European western styles through colonization. Each ethnic group has their own distinct dances; makes total dances in Indonesia are more than 3000 Indonesian original dances. However, the dances of Indonesia can be divided into three eras; the Prehistoric Era, the Hindu/Buddhist Era and the Era of Islam, and into two genres; court dance and folk dance.

There is a continuum in the traditional dances depicting episodes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata from India, ranging through Thailand, all the way to Bali. There is a marked difference, though, between the highly stylized dances of the courts of Yogyakarta and Surakarta and their popular variations. While the court dances are promoted and even performed internationally, the popular forms of dance art and drama must largely be discovered locally.

During the last few years, Saman from Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam has become rather popular and is often portrayed on TV.

Drama and theatre

Wayang, the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese shadow puppet theatre shows display several mythological legends such as Ramayana and Mahabharata, and many more. Wayang Orang is Javanese traditional dance drama based on wayang stories. Various Balinese dance drama also can be included within traditional form of Indonesian drama. Another form of local drama is Javanese Ludruk and Ketoprak, Sundanese Sandiwara, and Betawi Lenong. All of these drama incorporated humor and jest, often involving audiences in their performance.

Randai is a folk theatre tradition of the Minangkabau people of West Sumatra, usually performed for traditional ceremonies and festivals. It incorporates music, singing, dance, drama and the silat martial art, with performances often based on semi-historical Minangkabau legends and love story.

Modern performing art also developed in Indonesia with their distinct style of drama. Notable theatre, dance, and drama troupe such as Teater Koma are gain popularity in Indonesia as their drama often portray social and political satire of Indonesian society.

See also

- Ethnic groups in Indonesia

- Culture of Indonesia

- Indonesian people

- List of Indonesian people

- National costume of Indonesia

- List of indigenous peoples

Non-Bumiputra Indonesians:

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 "Pribumi". Encyclopedia of Modern Asia. Macmillan Reference USA. Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 2006-10-05.

- ↑ 2008. "Foreign Workers by Country of Origin (1999 -2008) - Official Portal of Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister's Department Malaysia" (PDF). Economic Planning Unit. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ "Migrant Communities in Saudi Arabia", Bad Dreams: Exploitation and Abuse of Migrant Workers in Saudi Arabia, Human Rights Watch, 2004

- ↑ Media Indonesia Online 2006-11-30

- ↑ "Race Reporting for the Asian Population by Selected Categories: 2010", 2010 Census Summary File 1, U.S. Census Bureau, retrieved 2012-02-21

- ↑ Barnes & Bennett 2002, p. 9

- ↑ Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of. "Browse Statistics". www.abs.gov.au.

- ↑ Reporter, Binsal Abdul Kader, Staff (17 August 2009). "Expatriates celebrate 64th Indonesian Independence Day in Abu Dhabi". gulfnews.com.

- ↑ http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001530/153053e.pdf

- ↑ "Sunni and Shia Muslims". pewforum.org. 27 January 2011.

- ↑ Sharon Siddique and Leo Suryadinata, "Bumiputra and Pribumi: Economic Nationalism (Indiginism) in Malaysia and Indonesia", Pacific Affairs, Vol. 54, No. 4 (Winter, 1981-1982), pp. 662-687

- ↑ William H. Frederick and Robert L. Worden, Indonesia: A Country Study (Washington: Library of Congress, 6th ed., 2011), p. 409.

- ↑ Kwik Kian Gie, in Leo Suryadinata, Political Thinking of the Indonesian Chinese, 1900-1995: A Sourcebook (Singapore University Press, 2nd ed., 1977), p.135.

- ↑ Purdey, Jemma (2006). Anti-Chinese Violence in Indonesia, 1996–1999. Singapore: Singapore University Press. p. 179. ISBN 9971-69-332-1.

- ↑ Hasanah, Sovia (2017-10-17). "Dasar Hukum yang Melarang Penggunaan Istilah "Pribumi"" [Law that based ban of "Pribumi" term]. hukumonline.com. hukumonline.com. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ↑ Fujita Kayoko; Shiro Momoki; Anthony Reid, eds. (2013). Offshore Asia: Maritime Interactions in Eastern Asia Before Steamships, volume 18 from Nalanda-Sriwijaya series. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 97. ISBN 9814311774.

- ↑ Sidjaja, Calvin Michel (22 October 2011). "Who is responsible for 'Bersiap'?". The Jakarta Post.

- ↑ "Pribumi". KBBI (in Indonesian).

- ↑ The Library of Congress, Federal Research Division. "Glossary -- Indonesia". A Country Study: Indonesia. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ↑ Kuoni - Far East, A world of difference. Page 88. Published 1999 by Kuoni Travel & JPM Publications

- 1 2 Indonesia's Population: Ethnicity and Religion in a Changing Political Landscape. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 2003.

- 1 2 3 "Sebaran Suku Jawa Di Indonesia". www.kangatepafia.com. 18 May 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ↑ Bellwood, Peter. Pre-History of the Indo-malaysian Archipelago. Australian National University:1985. ISBN 978-1-921313-11-0

- ↑ Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca (29 September 1998). "The Chinese Human Genome Diversity Project". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (20): 11501–11503. More than one of

|website=and|journal=specified (help) - ↑ http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp175_chinese_civilization_agriculture.pdf The Rise of Agricultural Civilization in China, Sino-Platonic Papers 175, Zhou Jixu, citing Ho Ping-ti, ISBN 0-226-34524-6

- ↑ TAJIMA Atsushi, PAN I.-Hung, FUCHAROEN Goonnapa, FUCHAROEN Supan, MATSUO Masafumi, TOKUNAGA Katsushi, JUJI Takeo, HAYAMI Masanori, OMOTO Keiichi, HORAI Satoshi, "Three major lineages of Asian Y chromosomes: implications for the peopling of east and southeast Asia," Human Genetics 2002, vol. 110, no1, pp. 80-88

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, Mongoloid

- ↑ Ricklefs, M.C. (1994). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300. Stanford University Press.

- ↑ English Not On Menu For Wednesday's Press Briefing

- ↑ UNESCO, Angklung was officially recognized in Nov 18, 2010 at the Fifth Unesco Inter-Governmental Committee meeting on Intangible Cultural Heritage in Nairobi, Kenya.

- ↑ UNESCO grants Indonesia's angklung cultural heritage title Archived 2013-07-08 at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

- Center for Information and Development Studies. (1998) Pribumi dan Non-Pribumi dalam Perspektif Pemerataan Ekonomi dan Integrasi Sosial (Pribumi and Non-Pribumi in the Perspective of Economic Redistribution and Social Integration). Jakarta, Indonesia: Center for Information and Development Studies

- Suryadinata, Leo. (1992) Pribumi Indonesians, the Chinese Minority, and China. Singapore: Heinemann Asia.