Cyclone Val

| Category 4 severe tropical cyclone (Aus scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

Satellite image of Cyclone Val (center) and Cyclone Wasa | |

| Formed | December 4, 1991 |

| Dissipated | December 17, 1991 |

| (Extratropical after December 13, 1991) | |

| Highest winds |

10-minute sustained: 165 km/h (105 mph) 1-minute sustained: 230 km/h (145 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 940 hPa (mbar); 27.76 inHg |

| Fatalities | 16 direct |

| Damage | $301 million (1991 USD) |

| Areas affected | Tuvalu, Tokelau, Wallis and Futuna, Samoa, American Samoa, Cook Islands, Tonga |

| Part of the 1991–92 South Pacific cyclone season | |

Severe Tropical Cyclone Val was considered to be the worst tropical cyclone to affect the Samoan Islands since the 1889 Apia cyclone.

The cyclone lasted for five days in American Samoa and was designated by the United States Government as a major disaster on December 13, 1991. Western Samoa suffered more damage than American Samoa.[1][2][3][4] The cyclone devastated the islands with 150-mile-per-hour (240 km/h) winds and 50-foot (15 m) waves. The overall damages caused by Cyclone Val in American Samoa have been variously assessed. One estimate put the damages at $50 million in American Samoa and $200 million in Western Samoa due to damage to electrical, water, and telephone connections and destruction of various government buildings, schools, and houses.[5][6]

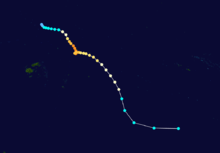

Meteorological history

On December 1, 1991 the Fiji Meteorological Service started to monitor a small circulation, that had developed along the Intertropical Convergence Zone, just to the north of Tokelau as a result of a surge within the westerlies.[7][8] Over the next two days, the system moved westwards towards Rotuma and Tuvalu, where it lied near the centre of an upper level outflow mechanism.[8] During December 4, as the system continued to develop, it was classified as a depression by the FMS, while it was located just to the southeast of Tuvalu and moving towards the northwest. Early the next day the system was named Val by the FMS, after it had become a category 1 tropical cyclone on the Australian tropical cyclone intensity scale.[9][10] During that day the United States Naval Western Oceanography Center (NWOC) designated the system as Tropical Cyclone 06P and started to issue advisories, while Val started to move towards the south-southeast after the upper level north-westerly steering winds had increased.[10][11] During December 6, the NWOC reported that the system had become equivalent to a category 2 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale as Val continued to steadily intensify and moved south-eastwards, away from Tuvalu and towards Western Samoa.[7][12] Early on December 7, the FMS reported that the system had become a category 3 severe tropical cyclone as the cyclone started to be steered southwards by upper-level northerlies.[7][9]

Later that day TCWC Nadi reported that Val had reached its peak 10-minute sustained windspeeds of about 165 km/h (105 mph), which made it a category 4 severe tropical cyclone on the Australian scale.[9][13] The system subsequently made landfall on the Western Samoan island of Savaii at around 1800 UTC, before the NWOC reported that the cyclone had peaked with 1-minute sustained windspeeds of about 230 km/h (145 mph), which made it equivalent to a category 4 hurricane on the SSHS.[10][12] After Val had passed over the island weakening upper level winds and caused the system to slow down, before it started to move erratically and made a sharp clockwise loop which almost brought it over Savaii for a second time.[10][14] During December 9, Val completed its loop and started to move eastwards while starting to gradually weaken, before it passed over the American Samoan island of Tutuila early the next day.[14] After passing over American Samoa, Val initially threatened the Southern Cook Islands but changed direction during December 11 and curved more towards the south-southeast while continuing to weaken, which spared it the worst of the cyclone.[13] During December 12, TCWC Nadi reported that Val had weakened into a category two tropical cyclone and passed the primary warning responsibility for the system to the New Zealand Meteorological Service (TCWC Wellington) after Val had moved out of its area of responsibility.[13] Shortly after moving into TCWC Wellington's area of responsibility, Val transitioned into an extratropical depression.[14] Storm force winds subsequently persisted around the center of Val's remnants for the next 3 days, before the system was captured and sheared apart by strong environmental westerlies associated with the Antarctic Circumpolar Current as it approached 50°S.[14]

Preparations and impact

| Area | Damages (USD) | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| American Samoa | $100 million | [15] |

| Cook Islands | $544 thousand | [16] |

| Tokelau | $394 thousand | [16] |

| Tonga | Minor | [7] |

| Tuvalu | None | [7] |

| Wallis and Futuna | None | [7] |

| Western Samoa | $280 million | [7][17] |

| Total | $301 million |

Severe Tropical Cyclone Val was responsible for over US$300 million worth of damage and caused 16 deaths, as it impacted Tokelau, Tuvalu, Samoa, American Samoa, the Cook Islands, Tonga, Wallis and Futuna. The systems worst impact was reported in the Samoan Islands, where it was considered to be the worst tropical cyclone to affect Samoa since the 1889 Apia cyclone.[18] As a result of the impact of this storm, the name Val was retired from the tropical cyclone naming lists.[19]

As the initial depression developed near Tuvalu, the FMS issued a strong wind warning for both Tuvalu and Tokelau, before they issued a gale warning for Tokelau during December 6.[7] During that day, gale force winds were experienced within the island nation, as it passed within 370 km (230 mi) of Tokelau.[7] The warning was cancelled later that day, as the system moved south-eastwards away from the islands.[7] The strong wind warning for Tokelau was maintained throughout Val's lifetime, however, there was no significant damage reported in either island nation.[7][20] As the system moved south-eastwards it posed a reasonable threat to Wallis Island, with a gale warning issued by the FMS during December 6.[7] However, during that day the system moved away from Wallis and the gale warning was cancelled, after the island had reported no damage or gale force winds.[7]

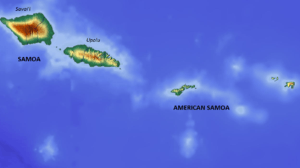

Samoan Islands

Val impacted the Samoan Islands for four days and nights between December 6–11, while the nations were still recovering from the effects of Cyclone Ofa, which impacted the islands during February 1990.[7] During December 6, after it had become obvious that Val was going to affect the Samoan Islands with gale-force or stronger winds, the FMS issued gale warnings for both island nations.[7] Hurricane warnings were subsequently issued for the both nations during the next day, before communications with Western Samoa were lost as the system made landfall on Savaii.[7] By this time the system had started to move erratically, which prompted the FMS to downgrade the hurricane warning for American Samoa to a gale warning early on December 8.[7] During that day, Val completed a clockwise loop and started to move eastwards towards American Samoa directly.[7] This prompted the FMS to reissue the hurricane warning for American Samoa during December 9, before they gradually adjusted them as the system passed directly over Tutila and accelerated south-eastwards away from the Samoa's.[7]

The cyclone destroyed over 65% of the residential homes on American Samoa and even more on the Samoan islands of Upolu and Savai'i.[3] Cyclone Val cut communications and power lines on the islands. It devastated fire stations, hospitals, government buildings, schools, and churches, particularly wooden buildings of the pre World War I colonial era. Cyclone Val destroyed over 80% of agricultural crops.[3] One of the first areas hit was the Western Samoan island of Savai'i, which was described as looking like an atomic bomb had hit. A local remarked that "there was no green, no buildings standing, no shelter; just total and complete devastation."[3] Cyclone Val was reported to have killed 17 people and left 4,000 people homeless in American Samoa alone.[3] Cyclone Val was assessed to have had an impact 50% worse than Cyclone Ofa,[3] costing about $50 million in damage and putting a severe strain on agricultural production and the livelihoods of farmers on the islands.[6] In Fagatele Bay at Tutuila Island, where Cyclone Val made a direct pass, the coral reef was completely destroyed. A large strip of the coast was also eroded. In response to this disaster, the NOAA deputed an assessment team to survey the damage to the reefs.[21] In Tutuila, which accounts for 68% of American Samoa, the funicular railway, the longest single span cable way in the world, was permanently put out of service by Cyclone Val.[22] The cable had previously connected Pago Pago harbor with the TV tower erected on Mt. Alava (491m). The TV tower at Utulei, one of the three TV channels in Samoa, was completely ruined by Cyclone Val, resulting in it being cannibalized for parts to maintain the two remaining channels.[23] The Fagalele Boys School, one of the oldest European-style buildings on the island in Leone, was destroyed by Cyclone Val.[24] According to a report of Greenpeace mission, the airport of Western Samoa was also devastated.

The damage caused by Cyclone Val was severe, as it occurred 18 months after Cyclone Ofa (February 1990). Food production was halted; forests were damaged, and animals and birds were lost. The forest loss was as severe as 45% of Savai'i's timber logs.[25]

.jpg)

People were devoid of electricity for weeks and water supply for many days and depended on emergency aid. In Western Samoa (islands of Savai'i, Manono and Upolu), the percentage of damaged houses was as high as 80%.[26]

Val was reported as the worst cyclone to hit the Samoas in 100 years (since the 1889 hurricane), as measured by the intensity of the wind and the severity of the damage it caused to the islands.[27] The President of the United States declared the event as a "major disaster", for which federal assistance was provided.[28] The severity of Cyclone Val was aptly described by a local resident who stated: "But this Cyclone was stronger than me. For the first time I felt defeated I had never felt that before. I felt it was personal between me and Cyclone. I got depressed afterward."[29]

Aid was provided to the affected zones based on a categorization as Category A, B, C, D, E and F. The categories are defined by the degree of damage suffered. Assistance covered individuals, households, and the State and local governments. The assistance encouraged private, nonprofit organizations (NGOs) to meet and discuss expense-related emergency work and the repair or replacement of disaster-damaged infrastructure. Assistance provided "Hazard Mitigation Grants" to secure life and property from hazards.[2]

New Zealand and Australia provided considerable assistance to the affected population and helped with the reconstruction and recovery of infrastructure facilities. Samoans in the United States, Australia, and New Zealand helped finance the recovery by way of remittances to their relatives who suffered on the island.[25]

Aftermath

American Samoa

Law suit

In 1991, American Samoa purchased a $45 million "all risk" insurance policy from the firm Affiliated FM Insurance. The firm would only pay up to $6.1 million for the damages, arguing that the insurance did not cover water damage, only that caused by the wind.[6] Attorney William Shernoff investigated and discovered that the insurance company had altered American Samoa's insurance policy to exclude damages caused by "wind-driven water", despite the fact that it still covered cyclones.[6] The case was taken to court, and in 1995, the jury awarded the American Samoa Government $28.9 million. Soon after, the amount was doubled to $57.8 million to include punitive damages. The total damages awarded by the judgment was $86.7 million, which the judge stated to be "the largest insurance bad faith verdict in the state of California in 1995".[6]

The revenues of American Samoa for the fiscal years 2002 and 2003, which had been showing a downward trend, registered a substantial increase attributed to the insurance settlement of claims made to cover the damages caused by Cyclone Val. This resulted in fiscal surpluses. The deficit of US $23.1 million at the start of 2001 changed to a surplus of US $43.2 million by end of 2003.[30]

References

- ↑ "American Samoa Cyclone Val". FEMA.gov. Archived from the original on June 3, 2010. Retrieved December 16, 2010.

- 1 2 "American Samoa Cyclone Val Major Disaster Declared December 13, 1991". US Department of Homeland Security:FEMA. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Cyclone Wreaks Ruin in Samoa". The Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints. December 21, 1991. Retrieved December 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Effect of Cyclone Val on areas proposed for inclusion in the National Park of American Samoa" (PDF). A report to the U.S. National Park Service. Botany.hawaii.edu. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 4, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ↑ Gill, Jonathan P. (September 3, 1994). "The South Pacific and Southeast Indian Ocean Tropical Cyclone Season 1991–1992" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine. Australian Bureau of Meteorology: 181–192. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Representing An Entire Country: American Samoa Government v. Affiliated FM Insurance". Shernoff. Archived from the original on August 24, 2010. Retrieved December 16, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Pandaram, Sudha; Prasad, Rajendra (July 7, 1992). Tropical Cyclone Val, December 4 - 13, 1991 (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report 91/2). Fiji Meteorological Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- 1 2 Ward, Graham F.A (March 1, 1995). "Prediction of tropical cyclone formation in terms of sea-surface temperatures vorticity and vertical windshear" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 44 (1): 63–64. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 MetService (May 22, 2009). "TCWC Wellington Best Track Data 1967–2006". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship.

- 1 2 3 4 Fiji Meteorological Service (1992). DeAngellis, Richard M, ed. "Hurricane Alley: Cyclones of the Southeast Pacific Ocean 1990–1991: Tropical Cyclone Val, December 4 - 13, 1991". Mariners Weather Log. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Oceanographic Data Center. 36 (4: Fall 1992): 56. hdl:2027/uiug.30112104094179. ISSN 0025-3367. OCLC 648466886.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Western Oceanography Center (1993). 4. Summary of South Pacific and South Indian Tropical Cyclones (PDF) (1992 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report). United States Navy, United States Airforce. pp. 183 , - 190. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- 1 2 Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center; Joint Typhoon Warning Center. "Tropical Cyclone 06P (Val) best track analysis". United States Navy, United States Air Force. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Pandaram, Sudha; Nadi Tropical Cyclone Warning Center (1992). Tropical Cyclone Val, December 4 - 13, 1991 (Tropical Cyclone Report 91/2). Fiji Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on April 28, 2013. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Gill, Jonathan P. "The South Pacific and Southeast Indian Ocean Tropical Cyclone Season 1991–1992" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 43: 181 , – 192. ISSN 1836-716X. OCLC 469881562. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center. Goodge, Grant W, ed. "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena: December 1991" (PDF). 33 (12). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service: 58. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2017. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- 1 2 http://www.pacificdisaster.net/pdnadmin/data/original/WSM_TC_1991_sitrep1_8.pdf

- ↑ Fairbairn, T. (1997). The economic impact of natural disasters in the South Pacific with special reference to Fiji, Western Samoa, Niue, and Papua New Guinea (PDF). South Pacific Disaster Reduction Program. ISBN 982-364-001-7.

- ↑ Ashcroft, Paul; Ward, R. Gerard (1998). Samoa: mapping the diversity. pp. 11–29. ISBN 982-02-0134-9.

- ↑ RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee (December 12, 2012). "List of Tropical Cyclone Names withdrawn from use due to a Cyclone's Negative Impact on one or more countries". Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South-East Indian Ocean and the Southern Pacific Ocean 2012 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. pp. 2B–1–2B-4 (23–26). Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ Barstow, Stephen F; Haug, Ola (November 1994). The Wave Climate of Tuvalu (PDF) (SOPAC Technical Report 203). South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Fagatele Bay Marine Sanctuary". Research and Monitoring. Official Site of the Fagatele Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ↑ Stanley, p. 475

- ↑ Stanley, pp. 475–477

- ↑ Stanley, p. 480

- 1 2 Ward, pp. 20–21

- ↑ "Storm of the Century Devastates the Samoas for the Second Year Running". Greenpeace.org. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ↑ Ward, pp. 17–21

- ↑ "FEMA posts 11 disaster declarations for territory over last 40 yrs". Samoanews. November 4, 2010. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ↑ Gold, Jerome (1994). Cyclones. Black Heron Press. pp. 77, 80. ISBN 0-930773-25-X. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ↑ U.S. Insular Areas: Economic, Fiscal, & Financial Accountability Challenges. DIANE Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 1-4223-1153-8. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

Bibliography

- Stanley, David (2004). Moon Handbooks South Pacific. David Stanley. ISBN 1-56691-411-6. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

External links

- World Meteorological Organization

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- Fiji Meteorological Service

- New Zealand MetService

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center