Mon people

| မွန်, မောန်, မည် | |

|---|---|

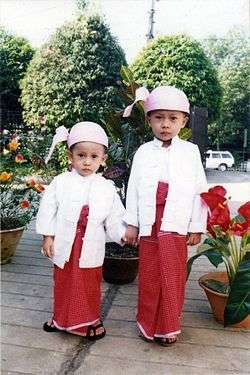

Mon boys in traditional Mon costume | |

| Total population | |

| c. 1.1 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| c. 1.1 million[lower-alpha 1][1] | |

| Languages | |

| Mon, Burmese, Thai | |

| Religion | |

| Theravada Buddhism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Austroasiatic peoples | |

The Mon (Mon: မောန် or မည်; Burmese: မွန်လူမျိုး, pronounced [mʊ̀ɴ lù mjó]; Khmer: មន, Thai: มอญ, pronounced [mɔ̄ːn]) are an ethnic group native to Myanmar's Mon State, Bago Region, the Irrawaddy Delta and the southern border with Thailand. One of the earliest peoples to reside in Southeast Asia, the Mon were responsible for the spread of Theravada Buddhism in Indochina. The Mon were a major source of influence on the culture of Myanmar. They speak the Mon language, an Austroasiatic language, and share a common origin with the Nyah Kur people of Thailand, they are from the Mon mandala (polity) of Dvaravati.

The eastern Mon include the current royal family of Thailand who are of Mon ancestry. The Mon assimilated to Thai culture long ago, yet the royal women of the Chakri dynasty perform and keep their Mon heritage alive in the Thai court. The western Mon of Myanmar were largely absorbed by Bamar society. They have worked to preserve their language and culture and to regain a greater degree of political autonomy.

Recent studies have adduced evidence indicating that the Mon and Bamar share some common genetic ancestry. A genetic study done on Mon from Southern Myanmar and Bamar from Southern Myanmar showed a high prevalence of a particular glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) mutation not found among Khmers, Laotians or Thais.[2]

Exonyms and endonyms

In the Burmese language, the term Mon မွန် (pronounced [mʊ̀ɴ]) is used. During the pre-colonial era, the Burmese used the term Talaing (တလိုင်း), which was subsequently adopted by the British, who also invariably referred to the Mon as Peguans, during the colonial era.[3] The etymology of Talaing is debated; it may be derived from Telangana or Kalinga, a geographic region in southeast India.[4] The use of "Talaing" predates the Burmese conquest of the Hanthawaddy Kingdom in the 1700s and has been found on inscriptions dating to the reign of Anawrahta in the 1000s.[4][5] In 1930 and 1947, Mon ethnic leaders, who considered the term "Talaing" to be pejorative (as it meant "bastard" or "downtrodden" in Mon), petitioned against the use of the term, which is now obsolete in modern Burmese. The Burmese term "Mon" is synonymous with the Burmese word for "noble."[6] In the Mon language, the Mon are known as the Mon (spelt မောန် or မန် and pronounced /mòn/), based on the Pali term Rāmañña (ရာမည), which refers to the Mon heartland along the Burmese coast.[7] In classical Mon literature, they are known as the Raman (ရာမန်).[3]

The Mon of Myanmar are divided into three sub-groups based on their ancestral region in Lower Myanmar:

History

Early history

The Mon were believed to be one of the earliest peoples of Indochina. They founded some of the earliest civilizations there, including Dvaravati in Central Thailand (whose culture proliferated into Isan), Sri Gotapura[9] in central Laos (modern Sikhottabong, Vientiane Prefecture) and Northeastern Thailand, Hariphunchai in Northern Thailand and the Thaton Kingdom.[10]:63,76–77 They were the first receivers of Theravada missionaries from Sri Lanka, in contrast to their Hindu contemporaries like the Khmer and Cham peoples. The Mon adopted the Pallava alphabet and the oldest form of the Mon script was found in a cave in modern Saraburi dating around 550 AD. Though no remains were found belonging to the Thaton Kingdom, it was mentioned widely in Bamar and Lanna chronicles. The legendary Queen Camadevi from the Chao Phraya River Valley, as told in the Northern Thai Chronicle Cāmadevivaṃsa and other sources, came to rule as the first queen of Hariphunchai (modern Lamphun) kingdom around 800 AD.

After 1000 AD onwards the Mon were under constant pressure. With the Tai peoples migrating from the north and Khmer invasions from the east, the Mons of Dvaravati gave their way to the Lavo Kingdom by around 1000 AD. Descendants of the Dvaravati Mon people are the Nyah Kur people of Isan. The Mon were killed in wars, transported as captives, or assimilated into new cultures. The Mon as an entity virtually disappeared in Chao Phraya Valley. However, Hariphunchai kingdom survived as a Mon outpost in northern Thailand under repeated harassment by the Northern Thai people.

In 1057, King Anawrahta of Pagan Kingdom conquered the Thaton Kingdom. The Mon culture and the Mon script were readily absorbed by the Burmese and the Mons, for the first time, came under Bamar rule. The Mon remained a majority in Lower Burma.

Hariphunchai prospered in the reign of King Aditayaraj (around early twelfth century), who allegedly waged wars with Suryavarman II of Angkor and constructed the Hariphunchai stupa. In 1230, Mangrai, the Northern Thai chief, conquered Hariphunchai and the Mon culture was integrated into Lanna culture. The Lanna adopted the Mon script and religion.

In 1287, the Pagan Kingdom collapsed, leaving the power vacuum. Wareru, who was born from a Mon mother and a Tai father, at Domwon Village in the Thaton District, went to Sukhothai for merchandise and later eloped with a daughter of the king. He established himself in Mottama and was proclaimed king of the Mon. The capital was later moved to Bago. His Hanthawaddy Kingdom (1287–1539) was a prosperous period for the Mon in both power and culture. The Mon were consolidated under King Rajathiraj (1383–1422), who successfully fended off invasions by the Bamar Ava Kingdom. The reigns of Queen Shin Sawbu (1453–1472) and King Dhammazedi (1472–1492) were a time of peace and prosperity.

The Bamar, however, regained their momentum at Taungoo in the early sixteenth century. Hanthawaddy fell to the invasion of King Tabinshwehti of Taungoo in 1539. After the death of the king, the Mon were temporarily freed from Bamar rule by Smim Htaw, but they were defeated by King Bayinnaung in 1551. The Bamar moved their capital to Bago, keeping the Mon in contact with royal authority. Over the next two hundred years, the Mon of Lower Burma came under Bamar rule.

Lower Burma became effectively war fronts between the Bamar, the Thai and the Rakhine people. Following King Naresuan’s campaigns against the Bamar, the Mon were, either forced or voluntarily, moved to Thailand. The collapse of Mon power propagated waves of migration into Thailand, where they were permitted to live in city of Ayutthaya. A Mon monk became a chief advisor to King Naresuan.

Bago was plundered by the Rakhine in 1599. Bamar authority collapsed and the Mon loosely established themselves around Mottama. Only with the unification of King Anaukpetlun in 1616 were the Mon again under the rule of the Bamar. The Mon rebelled in 1661 but the rebellion was put down by King Pye Min. Mon refugees were granted residence in western Thailand by the Thai king. The Mons then played a major role in Thai military and politics, as they would later established the Chankri Dynasty of Thailand. A special regiment was created for the Mon serving the Thai king.

Bamar power declined rapidly in the early eighteenth century. Finally, the Mon rebelled again at Bago in 1740 with the help of the Gwe Shan people. A Bamar monk with Taungoo royal lineage was proclaimed king of Bago and was later succeeded by Binnya Dala in 1747. With the French support, the Mon were able to establish an independent kingdom for 17 years before falling to Alaungpaya in 1757. Alaungpaya, the Bamar ruler U Aungzeya, invaded and devastated the kingdom, killing tens of thousands of Mon, including learned Mon priests, pregnant women, and children. Over 3000 priests were massacred by the victorious Bamar in the capital city alone. Thousands more priests were killed in the countryside. Alaungpaya's army was hugely supported by the British army. This time, Bamar rule was harsh. The Mon were largely massacred, encouraging a large migration to Thailand and Lanna.

The Mon rebelled at Dagon in the reign of Hsinbyushin of the Konbaung Dynasty and the city was razed to the ground. Again in 1814 the Mons rebelled and were, as harshly as before, put down. These rebellions generated a huge wave of migrations that the Child-Prince Mongkut proceeded to welcome the Mon himself. Mongkut himself and the Chankri dynasty of Thailand today are Mon descendants. Thongduang or Rama I was born in 1737 in the reign of King Boromakot of Ayutthaya. Rama I father was Thongdi, a Mon noble serving the royal court Of Ayuthaya

The Mon in Thailand settled mainly in certain areas of Central Thailand, such as Pak Kret in Nonthaburi, Phra Pradaeng in Samut Prakan and Ban Pong, among other minor Mon settlements. Mon communities built their own Buddhist temples. Over time, the Mons were effectively integrated into Siamese society and culture, although maintaining some of their traditions and identity.[11]

Colonial period

Burma was conquered by the British in a series of wars. After the Second Anglo-Burmese War, the Mon territories were completely under the control of the British. The British aided the Mons to free themselves from the rule of the Burman monarchy. Under Burman rule, the Mon people had been massacred after they lost their kingdom and many sought asylum in the Thai Kingdom. The British conquest of Burma allowed the Mon people to survive in Southern Burma.

Post-independence

The Mon soon became anti-colonialists and, following the grant of independence to Burma in 1948, they sought self-determination. U Nu refused them this and they rose in revolt to be crushed again.

They have remained a repressed and defiant group in the country since then. They have risen in revolt against the central Burmese government on a number of occasions, initially under the Mon People's Front and from 1962 through the New Mon State Party. A partially autonomous Mon state, Monland, was created in 1974 covering Tenasserim, Pegu and Ayeyarwady River. Resistance continued until 1995 when NMSP and SLORC agreed a cease-fire and, in 1996, the Mon Unity League was founded.

In 1947, Mon National Day was created to celebrate the ancient founding of Hanthawady, the last Mon Kingdom, which had its seat in Pegu. (It follows the full moon on the 11th month of the Mon lunar calendar, except in Phrapadaeng, Thailand, where it is celebrated at Songkran).

The largest Mon refugee communities are currently in Thailand, with smaller communities in the United States (the largest community being in Fort Wayne, Indiana and the second largest being Akron, Ohio), Australia, Canada, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and the Netherlands.

Language and script

The Mon language is part of the Monic group of the Mon–Khmer family, closely related to the Nyah Kur language and more distantly related to Khmer. The writing system is Indic based. The Burmans adapted the Mon script for Burmese following their conquest of Mon territory during Anawrahta's reign.

Traditional culture

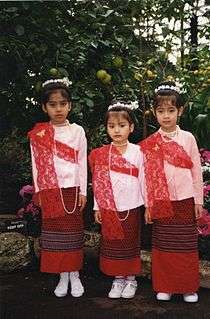

Mon culture and traditional heritages includes spiritual dances, musical instruments such as the kyam or "crocodile xylophone", the saung harp and a flat stringed instrument. Mon dances are usually played in a formal theater or sometimes in an informal district of any village. The dances are followed by background music using a circular set of tuned drums and claps, crocodile xylophone, gongs, flute, flat guitar, harp, etc. Mon in Burma wear clothes similar to the Bamars. Those living in Thailand have adopted Thai style scarfs and skirts.

The symbol of the Mon people is the hongsa (Mon: ဟံသာ, [hɔŋsa]), a mythological water bird that is often illustrated as a swan. The hongsa is the state symbol of Bago Region and Mon State, two historical Mon strongholds. It is commonly known by its Burmese name, hintha (Burmese: ဟင်္သာ, IPA: [hɪ́ɴθà]).

List of notable Mon (1900s–present)

- Kyaw Thet (1921–2008), historian

- Luangpho Ajahn Tala Uttama

- Mi Mi Khaing (1916–1990), Scholar

- Min Thu Wun, writer, father of President Htin Kyaw

- Min Ko Naing, whose parents are a mon couple from Mudon in Mon State.

See also

- Haripunchai

- History of Burma

- List of Mon monarchs

- Mon Nationalism and Civil War in Burma

- Mawlamyaing, the capital of Mon State in Burma

- Nyah Kur language

- Bago, Burma, Capital of Mon Kingdom

- University of Mawlamyaing

- Rev. Uttama

Further reading

- 'Historic Lamphun: Capital of the Mon Kingdom of Haripunchai', in: Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai Volume 4. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006J541LE

- Mon Nationalism and Civil War in Burma

Notes

- ↑ According to CIA Factbook, the Mon make up 2% of the total population of Myanmar (55 million) or approximately 1.1 million people.

- ↑ . cia.gov https://web.archive.org/web/20180117070224/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/bm.html. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Nuchprayoon 2007.

- 1 2 South, Ashley (2013-01-11). Mon Nationalism and Civil War in Burma: The Golden Sheldrake. Routledge. ISBN 9781136129629.

- 1 2 Miscellaneous Notes on the Word "Talaing".

- ↑ Aung-Thwin, Michael A., ed. (2005), "The Mon Paradigm and the Myth of the "Downtrodden Talaing"", The Mists of Ramanna, The Legend That Was Lower Burma, University of Hawai'i Press, pp. 261–280, ISBN 9780824828868, retrieved 2018-09-12

- ↑ "SEAlang Library Burmese Lexicography". sealang.net. Retrieved 2018-09-12.

- ↑ "Rāmañña - oi". doi:10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100402836.

- 1 2 3 Stewart 1937.

- ↑ "Sri Gotapura". Archived from the original on 2014-10-31. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

- ↑ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella, ed. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ↑ Wat's the centre of Mon tradition - Bangkok Post

References

- Nuchprayoon, Issarang; Louicharoen, Chalisa; Warisa Charoenvej (2007). "Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase mutations in Mon and Burmese of southern Myanmar". Journal of Human Genetics. 53 (1): 48–54. doi:10.1007/s10038-007-0217-3. PMID 18046504.

- Stewart, J. A. (1937). "The Song of the Three Mons". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 9 (1): 33–39. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00070725. JSTOR 608173.

External links

- Independent Mon News Agency

- Dating and Range of Mon Inscriptions

- Kao Wao News Group

- The Mon Information Home Page

- Mon state's profile

- Mon Music