LGBT symbols

| LGBT symbols |

|---|

| Flags |

| Other symbols |

| Part of a series on |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people |

|---|

|

|

|

The LGBT community has adopted certain symbols for self-identification to demonstrate unity, pride, shared values, and allegiance to one another. LGBT symbols communicate ideas, concepts, and identity both within their communities and to mainstream culture. The two most-recognized international LGBT symbols are the pink triangle and the rainbow flag. The pink triangle, employed by the Nazis in World War II as a badge of shame, was re-appropriated but retained negative connotations. The rainbow flag, previously used as a symbol of unity among all people, was adopted to be a more organic and natural replacement without any negativity attached to it.

Flag

Rainbow

Gilbert Baker designed the rainbow Pride flag for the 1978 San Francisco Gay Freedom Celebration. The flag does not depict an actual rainbow. Rather, the colors of the rainbow are displayed as horizontal stripes, with red at the top and violet at the bottom. It represents the diversity of gays and lesbians around the world. In the original eight-color version, pink stood for sexuality, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for the sun, green for nature, turquoise for art, indigo for harmony, and violet for spirit.[1] A copy of the original 20-by-30 foot, eight-color flag was remade by Baker in 2000, and was installed in the Castro district in San Francisco.[2] Another similar flag flies at The Center in New York City.

Original eight-stripe version designed by Gilbert Baker in 1978

Original eight-stripe version designed by Gilbert Baker in 1978 Version with hot pink removed due to a lack of fabric. (1978–1979)

Version with hot pink removed due to a lack of fabric. (1978–1979) Six-color version popular since 1979

Six-color version popular since 1979

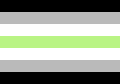

Asexuality

The asexual pride flag consists of four horizontal stripes: black, grey, white, and purple from top to bottom.[3][4][5][6]

In August 2010, after a process of getting the word out beyond the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN)[7] and to non-English speaking areas, a flag was chosen[8] following a vote on a non-AVEN site.[9] It has since been seen used on Tumblr in various LGBT areas, but had been seen alongside other sexual orientation flags previous to formal election.[10] The black stripe represents asexuality, the grey stripe representing the grey-area between sexual and asexual, the white stripe sexuality, and the purple stripe community.

The AVEN logo is a triangle fading from white to black to symbolise the gradient between sexuals, gray-asexuals, demisexuals, and asexuals.

The ace of spades and ace of hearts are also used as asexual symbols as "ace" is a phonetic shortening of asexual. Similarly, "aro" is commonly another abbreviation of aromantic. Generally, romantic asexuals use the ace of hearts as their symbol, and aromantic asexuals use the ace of spades.[11]

Another common symbol for the asexual community is a black ring worn on the middle finger of their right hand. The material and exact design of the ring are not important as long as it is primarily black. This symbol also found its start on AVEN in 2005.[12]

Bear culture

Bear is an affectionate gay slang term for those in the bear communities, a subculture in the gay community and an emerging subset of the LGBT community with its own events, codes, and culture-specific identity. Bears tend to have hairy bodies and facial hair; some are heavy-set; some project an image of working-class masculinity in their grooming and appearance, though none of these are requirements or unique indicators. The bear concept can function as an identity, an affiliation, and an ideal to live up to. There is ongoing debate in bear communities about what constitutes a bear. Some state that self-identifying as a bear is the only requirement, while others argue that bears must have certain physical characteristics, such as a hairy chest and face, a large body, or a certain mode of dress and behavior.

Bears are almost always gay or bisexual men; transgender men (regardless of their sexuality) and those who shun labels for gender and sexuality are increasingly included within bear communities. The bear community has spread all over the world, with bear clubs in many countries. Bear clubs often serve as social and sexual networks for older, hairier, sometimes heavier gay and bisexual men, and members often contribute to their local gay communities through fundraising and other functions. Bear events are common in heavily gay communities.

The International Bear Brotherhood Flag was designed in 1995 by Craig Byrnes.[13]

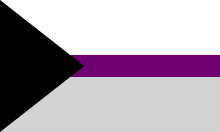

Bisexuality

First unveiled on 5 December 1998,[14] the bisexual pride flag was designed by Michael Page to represent and increase visibility of bisexuals in the LGBT community and society as a whole. This rectangular flag consists of a broad magenta stripe at the top, a broad stripe in blue at the bottom, and a narrower deep lavender band occupying the central fifth.

Page describes the meaning of the pink, lavender, and blue (ratio 2:1:2) flag as this: "The pink color represents sexual attraction to the same sex only (gay and lesbian). The blue represents sexual attraction to the opposite sex only (straight) and the resultant overlap color purple represents sexual attraction to both sexes (bi)." He also describes the flag’s meaning in deeper terms, stating "The key to understanding the symbolism of the Bisexual pride flag is to know that the purple pixels of color blend unnoticeably into both the pink and blue, just as in the 'real world,' where bi people blend unnoticeably into both the gay/lesbian and straight communities.[15]

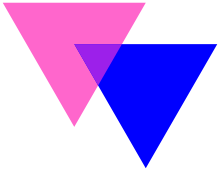

The blue and pink overlapping triangle symbol represents bisexuality and bi pride. The origin of the symbol, sometimes facetiously referred to as the "biangles", is largely unknown, however the colours of bisexuality originate from this symbol: pink for attraction to women, blue for attraction to men, and lavender for attraction to both, as well as a reference to queerness.[15]

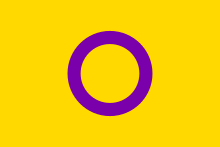

Intersex

Intersex people are those who do not exhibit all the biological characteristics of male or female, or exhibit a combination of characteristics, at birth. Between 0.05% and 1.7% of the population is estimated to have intersex traits.[16][17]

The intersex pride flag was created by Organisation Intersex International Australia in July 2013 to create a flag "that is not derivative, but is yet firmly grounded in meaning". The organisation aimed to create a symbol without gendered pink and blue colors. It describes yellow and purple as the "hermaphrodite" colors. The organisation describes it as freely available "for use by any intersex person or organisation who wishes to use it, in a human rights affirming community context".[18][19][20]

Lesbianism

The labrys lesbian pride flag, created in 1999,[21] involves a labrys superimposed on an inverted black triangle, set against a violet hue background. The labrys was used as an ancient religious symbol[22] and for other various purposes.[23] It was adopted as a symbol of empowerment by the lesbian feminist community in the 1970s.[24][25][26]

Women considered asocial by the Third Reich because they did not conform to the Nazi ideal of a woman, which included homosexual females, were condemned to concentration camps and wore the black badge to identify them.[27][28] Some lesbians reclaimed this symbol as gay men reclaimed the pink triangle, and many lesbians also reclaimed the pink triangle although lesbians were not included in Paragraph 175 of the German criminal code.[27]

Pansexuality

The pansexual pride flag has been found on various Internet sites since mid-2010.[29] It has three horizontal bars that are pink, yellow and blue.[30] The pink band symbolizes women; the blue, men; and the yellow, those of a non-binary gender, such as agender, bigender or genderfluid.[29][31][15][32][33]

A "P" with the tail converted to an arrow with a cross is also sometimes used. It predates the flag and is still in use today. The cross on the "P"'s tail refers to the cross on the Venus or female symbol (♀), and the arrow refers to the arrow on the Mars or male symbol (♂).[34] While it does not technically have a name, it is sometimes colloquially referred to as "the pansexual symbol".

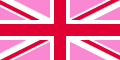

Pink jack (UK)

In the United Kingdom, since 2006 the Pink Jack has been widely used to represent a uniquely British LGBT identity.[35][36]

Transgender

A transgender symbol is the Transgender Pride Flag designed by transgender woman Monica Helms in 1999,[37] which was first shown at a pride parade in Phoenix, Arizona, USA in 2000.[38] It was flown from a large public flagpole in San Francisco's Castro District beginning November 19, 2012 in commemoration of the Transgender Day of Remembrance.[38] The flag represents the transgender community and consists of five horizontal stripes: two light blue, two pink, with a white stripe in the center. Helms described the meaning of the flag as follows:

- "The stripes at the top and bottom are light blue, the traditional color for baby boys. The stripes next to them are pink, the traditional color for baby girls. The stripe in the middle is white, for those who are intersex, transitioning or consider themselves having a neutral or undefined gender. The pattern is such that no matter which way you fly it, it is always correct, signifying us finding correctness in our lives.[38]

Philadelphia became the first county government in the U.S. to raise the transgender pride flag in 2015. It was raised at City Hall in honor of Philadelphia's 14th Annual Trans Health Conference, and remained next to the US and City of Philadelphia flags for the entirety of the conference. Then-Mayor Michael Nutter gave a speech in honor of the trans community's acceptance in Philadelphia.[39]

Also under the trans or transgender umbrella are all those who identify off the gender binary. There are many different identities within this category including genderqueer, two-spirit, gender fluid, third gender, and androgyny.[40]

Other symbols

In addition to major symbols of the LGBT community, less-popular symbols have been used to represent members’ unity, pride, shared values, and allegiance to one another.

Blue feather

In the Society for Creative Anachronism, LGBT members often wear a blue feather to indicate an affiliation with Clan Blue Feather, a group of SCA members promoting the study of LGBT culture and people in the Middle Ages.[41] Because of this affiliation, blue feathers have also been used at some Renaissance Faires and Pagan events.

Calamus plant

According to some interpretations, American poet Walt Whitman used the calamus plant to represent homoerotic love.[42]

Double-gender

Interlocked gender symbols. Each gender symbol derives from the astronomical symbol for the planet Venus and Mars. In modern science, the singular symbol for Venus is used to represent the female sex, and singular symbol for Mars is used to represent the male sex.[43] Two interlocking female symbols represent a lesbian or the lesbian community, and two interlocking male symbols a gay male or the gay male community.[44][45]

The symbols first appeared in the 1970s.[45]

Freedom rings

Freedom rings, designed by David Spada, are six aluminum rings, each in one of the colors of the rainbow flag. They were released in 1991.[46] Symbolizing happiness and diversity, these rings are worn by themselves or as part of necklaces, bracelets, and key chains.[46]

They are sometimes referred to as "Fruit Loops".[47]

Green carnation

In 19th-century England, green indicated homosexual affiliations. Victorian gay men would often pin a green carnation on their lapel as popularized by openly gay author Oscar Wilde, who often wore one on his lapel.[48][49]

Handkerchief code

In the early 20th century gay men in New York City's Caucasian professional world would often wear red neckties to signal their identity. This practice was later expanded into a system called flagging, or the hanky code.[50]

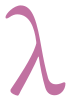

Lambda

In the early 1970s, graphic designer Tom Doerr selected the Greek letter lambda to be the symbol of the New York chapter of the Gay Activists Alliance.[51] The alliance's literature states that Doerr chose the symbol specifically for its denotative meaning in the context of chemistry and physics: "a complete exchange of energy–that moment or span of time witness to absolute activity".[51] Within the STEM field, the lambda symbol is associated with the half-life parameter of exponential random variables, which describes the time it takes for a state to change.

In December 1974, the lambda was officially declared the international symbol for gay and lesbian rights by the International Gay Rights Congress in Edinburgh, Scotland.[52] The gay rights organization Lambda Legal and the American Lambda Literary Foundation derive their names from this symbol.

Purple hand

On October 31, 1969, sixty members of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Society for Individual Rights (SIR) staged a protest outside the offices of the San Francisco Examiner in response to a series of news articles disparaging LGBT people in San Francisco's gay bars and clubs.[53][54] The peaceful protest against the "homophobic editorial policies" of the Examiner turned tumultuous and were later called "Friday of the Purple Hand" and "Bloody Friday of the Purple Hand".[54][55][56][57][58] Examiner employees "dumped a bag of printers' ink from the third story window of the newspaper building onto the crowd".[54][56] Some reports state that it was a barrel of ink poured from the roof of the building.[59] The protesters "used the ink to scrawl 'Gay Power' and other slogans on the building walls" and stamp purple hand prints "throughout downtown San Francisco" resulting in "one of the most visible demonstrations of gay power".[54][56][58] According to Larry LittleJohn, then president of SIR, "At that point, the tactical squad arrived – not to get the employees who dumped the ink, but to arrest the demonstrators. Somebody could have been hurt if that ink had gotten into their eyes, but the police were knocking people to the ground."[54] The accounts of police brutality include women being thrown to the ground and protesters' teeth being knocked out.[54][60]

Inspired by Black Hand extortion methods of Camorra gangsters and the Mafia,[61] some gay and lesbian activists attempted to institute "purple hand" as a warning to stop anti-gay attacks, but with little success. In Turkey, the LGBT rights organization MorEl Eskişehir LGBTT Oluşumu (Purple Hand Eskişehir LGBT Formation), also bears the name of this symbol.[62]

Unicorns

Unicorns have been part of pride flags and symbols of LGBT culture in the last century and It became prominent during the gay rights protests of the 1970s and 1980s.[63]

Violets

Violets became a special code used by lesbians and bisexual women.[64] The symbolism of the flower derives from several fragments of poems by Sappho in which she describes a lover wearing garlands or a crown with violets.[65][66][67][68] In 1926, the play La Prisonnière by Édouard Bourdet used a bouquet of violets to signify lesbian love.[69] When the play became subject to censorship, many Parisian lesbians wore violets to demonstrate solidarity with its lesbian subject matter.[70]

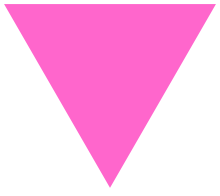

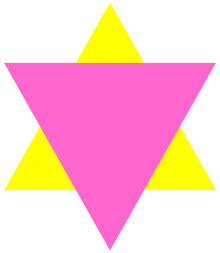

Triangle badges of the Third Reich

One of the oldest of these symbols is the inverted pink triangle that male homosexuals in Nazi concentration camps were required to wear on their clothing. The badge is one of several badges that internees wore to identify what kind of prisoners they were.[71] Many of the estimated 5–15,000 gay men and lesbians imprisoned in concentration camps died during the Holocaust.[72] The pink triangle was later reclaimed by gay men, as well as some lesbians, in various political movements as a symbol of personal pride and remembrance.[73][27] AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) adopted the inverted pink triangle to symbolize the "active fight back" against HIV/AIDS "rather than a passive resignation to fate."[74]

The pink triangle was used exclusively with male prisoners, as lesbians were not included under Paragraph 175, a statute which made homosexual acts between males a crime. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) stipulates that this was because women were seen as subordinate to men, and the Nazi state did not feel that homosexual women presented the same threat to masculinity as homosexual men. According to USHMM, many women were arrested and imprisoned for "asocial" behaviour, a classification applied to those who did not conform to the Nazi ideal of a woman's role: cooking, cleaning, kitchen work, child raising, and passivity. Asocial women were tagged with an inverted black triangle.[28] Many lesbians reclaimed this symbol for themselves as gay men reclaimed the pink triangle.[27]

| Pink Triangle | Black Triangle | Pink & Yellow Triangles |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| The inverted pink triangle used to identify homosexual men in the concentration camps. | The inverted black triangle used to mark individuals considered "asocial". The category included homosexual women, nonconformists, prostitutes, nomads, Romani, and others. | The inverted pink triangle overlapping a yellow triangle was used to single out male homosexual prisoners that were Jewish. |

LGBT pride flag gallery

See also

References

- ↑ "Carleton College: Gender and Sexuality Center: Symbols of Pride of the LGBTQ Community". Apps.carleton.edu. 2005-04-26. Archived from the original on 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ↑ Rochman, Sue (June 20, 2000). "Rainbow flap". The Advocate. p. 16. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ↑ Bilić, Bojan; Kajinić, Sanja (2016). Intersectionality and LGBT Activist Politics: Multiple Others in Croatia and Serbia. Springer. pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Decker, Julie. The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality. Skyhorse.

- ↑ "Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transexual: Symbols". Old Dominion University.

- ↑ "Asexual". UCLA Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Resource center.

- ↑ "The Creation of a Flag". Apositive.org. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ↑ "Asexual Flag: And the winner is". Asexuality.org. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ↑ "Asexual Flag - Round Three". Asexuality.org. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ↑ Queer Secrets

- ↑ AVEN. "AVEN Wiki". Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "Black rings and other ways to show asexual pride". Asexual Visibility and Education Network. Retrieved 2018-01-01.

- ↑ "Flag History". Bearmfg.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ↑ "History, Bi Activism, Free Graphics". BiFlag.com. 1998-12-05. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- 1 2 3 Petronzio, Matt (June 13, 2014). "A Storied Glossary of Iconic LGBT Flags and Symbols". Mashable. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ↑ https://www.unfe.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/UNFE-Intersex.pdf

- ↑ "How common is intersex? | Intersex Society of North America". Isna.org. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ↑ An intersex flag, Organisation Intersex International Australia, 5 July 2013

- ↑ Are you male, female or intersex? Archived 2016-09-23 at the Wayback Machine., Amnesty International Australia, 11 July 2013

- ↑ Intersex advocates address findings of Senate Committee into involuntary sterilisation Archived 2016-01-15 at the Wayback Machine., Gay News Network, 28 October 2013

- ↑ Sobel, Ariel (2018-06-13). "The Complete Guide to Queer Pride Flags". Advocate.com. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ Keller, Mara (1988). "Eleusinian Mysteries" (PDF). Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion (Vol 4 No 1): 42. Retrieved 2016-06-21.

- ↑ Caterina Mavriyannaki, "La double hache dans le monde héllenique à l'âge du bronze," Revue Archéologique, New series (1983:195-228).

- ↑ Cottingham, Laura (1996). Lesbians Are So Chic. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780304337217. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ↑ Murphy, Timothy (2013-10-18). Reader's Guide to Lesbian and Gay Studies. Routledge. p. 44ff. ISBN 9781135942342. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ↑ Pea, Georgie (9 August 2013). "LABRYS Tool of Lesbian Feminism". Finding Lesbians. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Elman, R. Amy. "Triangles and Tribulations: The Politics of Nazi Symbols". Remember.org. Retrieved 2016-12-10. (Originally published in the Journal of Homosexuality: 30 (3): 1–11, 1996, ISSN 0091-8369)

- 1 2 "Lesbians and the Third Reich". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Do You Have a Flag?". 9 November 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ↑ "Pansexual Pride Day". Shenandoah University. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ↑ "A field guide to Pride flags". 27 June 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ↑ "Cantú Queer Center - Sexuality Resources". Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ↑ "Gay & Lesbian Pride Symbols - Common Pride Symbols and Their Meanings". Archived from the original on 2016-09-28. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ↑ "Sexual Orientation Files: Pansexual". Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ "God save the queers". PinkNews.co.uk. 2006-07-21. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ↑ Pink Jack (image):

- ↑ Fairyington, Stephanie (12 November 2014). "The Smithsonian's Queer Collection". The Advocate. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Transgender Flag Flies In San Francisco's Castro District After Outrage From Activists" by Aaron Sankin, HuffingtonPost, November 20, 2012

- ↑ "Philadelphia Raises the Transgender Pride Flag for the First Time". The Advocate.

- ↑ GENDERQUEER AND NON-BINARY IDENTITIES - Genderqueer Identities & Terminology

- ↑ "Clan Blue Feather". Bluefeather.org. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑ Herrero-Brasas, Juan A. (2010). Walt Whitman's Mystical Ethics of Comradeship: Homosexuality and the Marginality of Friendship at the Crossroads of Modernity. SUNY. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4384-3011-9.

- ↑ Melissa (May 8, 2015). "The Origin of the Male and Female Symbols". Today I Found Out. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Bonnie, ed. (2000). "Symbols (by Christy Stevens)". Encyclopedia of Lesbian and Gay Histories and Cultures. 1 (Lesbian Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia) (1st ed.). Garland Publishing. p. 748. ISBN 0-8153-1920-7.

- 1 2 "Symbols of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Movements". lambda.org. LAMBDA GLBT Community Services. December 26, 2004. Archived from the original on December 30, 2005. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- 1 2 Van Gelder, Lindsy (1992-06-21), "Thing; Freedom Rings", New York Times, retrieved 2010-07-21

- ↑ Green, Jonathon (2006). Cassell's Dictionary of Slang. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 0-304-36636-6. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ↑ Stetz, Margaret D. (Winter 2000). Oscar Wilde at the Movies: British Sexual Politics and The Green Carnation (1960); Biography – Volume 23, Number 1, Winter 2000, pp. 90–107. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ Curiosities of Literature by John Sutherland (2011, ISBN 1-61608-074-4), pp. 73-76.

- ↑ George Chauncey (1994). Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. Basic Books. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-465-02621-0.

- 1 2 Rapp, Linda (2004). "Gay Activists Alliance" (PDF). The GLBTQ Encyclopedia Project. Glbtq, Inc.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Bonnie, ed. (1999). "Symbols". Encyclopedia of Lesbian and Gay Histories and Cultures (1 ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. p. 747. ISBN 978-0815340553.

- ↑ Gould, Robert E. (24 February 1974). What We Don't Know About Homosexuality. New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Alwood, Edward (1996). Straight News: Gays, Lesbians, and the News Media. Columbia University;

ISBN 0-231-08436-6. Retrieved 2008-01-01. templatestyles stripmarker in

|publisher=at position 22 (help) - ↑ Bell, Arthur (28 March 1974). Has The Gay Movement Gone Establishment?. Village Voice. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- 1 2 3 Van Buskirk, Jim (2004). "Gay Media Comes of Age". Bay Area Reporter. Archived from the original on 2015-07-05. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ↑ Friday of the Purple Hand. The San Francisco Free Press. November 15–30, 1969. Retrieved 2008-01-01. courtesy the Gay Lesbian Historical Society.

- 1 2 ""Gay Power" Politics". GLBTQ, Inc. 30 March 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ↑ Montanarelli, Lisa; Ann Harrison (2005). Strange But True San Francisco: Tales of the City by the Bay. Globe Pequot;

ISBN 0-7627-3681-X. Retrieved 2008-01-01. templatestyles stripmarker in

|publisher=at position 15 (help) - ↑ Newspaper Series Surprises Activists. The Advocate. 24 April 1974. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ↑ Jay Robert Nash, World Encyclopedia of Organized Crime, Da Capo Press, 1993. ISBN 0-306-80535-9

- ↑ "MorEl Eskişehir LGBTT Oluşumu". Moreleskisehir.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ↑ Fisher, Alice (2017-10-15). "Why the unicorn has become the emblem for our times | Alice Fisher". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-08-19.

- ↑ Horak, Laura (2016). "Lesbians Take Center Stage: The Captive (1926-1928)". Girls Will Be Boys: Cross-Dressed Women, Lesbians, and American Cinema, 1908-1934. Rutgers University Press. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-8135-7483-7.

- ↑ "Gay Symbols Through the Ages". The Alyson Almanac: A Treasury of Information for the Gay and Lesbian Community. Boston, Massachusetts: Alyson Publications. 1989. p. 100. ISBN 0-932870-19-8.

- ↑ Myers, JoAnne (2003). The A to Z of the Lesbian Liberation Movement: Still the Rage (The A to Z Guide Series, No. 73 ) (1st ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-8108-6811-3.

- ↑ Collecott, Diana (1999). H.D. and Sapphic Modernism 1910-1950 (1st ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 0-521-55078-5.

- ↑ Fantham, Elaine; Foley, Helene Peet; Kampen, Natalie Boymel; Pomeroy, Sarah B.; Shapiro, H. A. (1994). Women in the Classical World: Image and Text (1st ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-19-506727-9.

- ↑ Cohen-Stratyner, Barbara (January 14, 2014). "Violets and Vandamm". New York Public Library. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ↑ Sova, Dawn B. (2004). Banned Plays: Censorship Histories of 125 Stage Dramas (1st ed.). Facts On File. pp. 37–40. ISBN 0-8160-4018-4.

- ↑ Plant, Richard (1988). The pink triangle: the Nazi war against homosexuals (revised ed.). H. Holt. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-8050-0600-1.

- ↑ "Nazi Persecution of Homosexuals 1933-1945". Ushmm.org. Archived from the original on 2012-01-19. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ↑ Stier, Oren Baruch (2015). Holocaust Icons: Symbolizing the Shoah in History and Memory. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813574059.

- ↑ Cage, Ken; Evans, Moyra (2003-01-01). Gayle: The Language of Kinks and Queens : a History and Dictionary of Gay Language in South Africa. Jacana Media. ISBN 9781919931494.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LGBT symbols. |

- Origin & History of Gay & Lesbian Symbols shows images of some of these symbols and offers a brief historical account of each.