Black triangle (badge)

The black triangle was a badge used in Nazi concentration camps to mark prisoners regarded "asocial" and "arbeitsscheu" (work-shy). Those considered asocial included thieves, murderers, nomads, and Aryans who engaged in sexual relations with Jews. Women deemed to be asocial included prostitutes, nonconformists, and lesbians.

Usage

Nazi

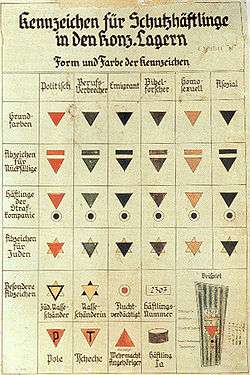

The symbol originates from Nazi Germany, where every prisoner had to wear a concentration camp badge on their jacket, of which the design and color categorized them according to the reason for their internment. The homeless were included, as were alcoholics, those who habitually avoided work and employment, draft dodgers, pacifists, Roma and Sinti people, and others.[1] Many black triangle prisoners were mentally disabled or mentally ill.[2]

Lesbians

| LGBT symbols |

|---|

| Flags |

| Other symbols |

Nazis considered homosexual women asocial and a threat to German society, and the badge was used to identify them.[3]

In the 1970s, the black triangle was first used as a symbol of pride and solidarity by lesbians in the United Kingdom; and its symbolic use was introduced in North America through the "women's peace camp movement".[4] It has also been adopted in remembrance of lesbians who suffered and died at the hands of Nazis.[5] Some lesbians wear it for "historical precision".[3]

Controversy over use

Before the rise of the Third Reich, lesbian sex was not a criminal offense in Germany and lesbians were not imprisoned solely because of their sexual preference;[6] and it was not criminalized under Paragraph 175 of the Nazi provision on sexual behavior that was added to the Strafgesetzbuch (German criminal code). However, lesbians incurred social discrimination and persecution by German police.[6]

Some people argue that lesbians were not subject to Paragraph 175 and disapprove of the use of the black triangle as a lesbian symbol.

The archive of the memorial site of Ravensbrück has evidence of four women with an additional remark of being lesbians: two of them had been persecuted for political reasons, two for being Jewish. One of the Jewish inmates was given a black triangle due to sexual contacts with non-Jews.[7]

Although the wearing of the black triangle by lesbians has been documented, some believe that the 1976 memoir Playing for Time (Sursis pour l'orchestra), by Fania Fénelon,[8] is the source which created the belief that the triangle was worn by them. Fénelon's memoir includes lesbian themes and describes an evening of entertainment in the asocials' barracks as the "Black Triangles' Ball."

Disabled people

Some UK groups concerned with the rights of disabled people have adopted the symbol in their campaigns.[9][10] Such groups cite press coverage and government policies, including changes to incapacity benefits and disability living allowance, as the reasons for their campaigns.[11][12] "The Black Triangle List" was created to keep track of welfare-related deaths due to cuts by the Department for Work and Pensions.[13]

Pharmacovigilance

The inverted black triangle was first used in the UK to indicate that a drug or vaccine is new and to monitor its usage.[14] The scheme was adopted by the European Union in 2013.[15][16]

See also

References

- ↑ The unsettled, "asocials", alcoholics and prostitutes. Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies. University of Minnesota. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ↑ Reddebrek (January 16, 2018). "Remembering the Black Triangles". libcom.org. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- 1 2 Elman PhD, R. Amy (1996). "Triangles and Tribulations: The Politics of Nazi Symbols". Journal of Homosexuality. 30 (3): 1–11. ISSN 0091-8369.

- ↑ Zoe, Lucinda (June 1991). "The Black Triangle" (PDF). Lesbian Herstory Archives Newsletter (12): 7. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Myers, JoAnne (2003). The A to Z of the Lesbian Liberation Movement: Still the Rage (The A to Z Guide Series, No. 73) (1st ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8108-6811-3. (2003 is original U.S. copyright.)

- 1 2 "Lesbians and the Third Reich". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Schoppmann, Claudia (1991). Nationalsozialistische Sexualpolitik und weibliche Homosexualität (in German) (2nd ed.). Centaurus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89085-538-7.

National Socialist Sexual Policy and Female Homosexuality

- ↑ Sterling, Eric (2002). "Playing for Time (Sursis Pour L'Orchestra)". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ "Black Triangle Campaign". Black Triangle Campaign.

- ↑ "DPAC – Disabled People Against Cuts". www.dpac.uk.net.

- ↑ "Black Triangle Campaign". 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Black Triangle Campaign". 13 December 2011.

- ↑ Laws, Vince (April 30, 2015). "UK Welfare-Related Deaths: The Black Triangle List". Disability Arts Online. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ "The Black Triangle Scheme (▼ or ▼*)". gov.uk. Government of the United Kingdom. 11 December 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ News team (1 October 2013). "Black triangle system rolled out across Europe". The Pharmaceutical Journal. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ "Medicines under additional monitoring". European Medicines Agency. 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

Further reading

- Marshall, Stuart. "The Contemporary Use of Gay History: The Third Reich," in Bad-Object Choices (ed.), How Do I Look? Queer Film and Video, Seattle, Wash.: Bay Press, 1991.