Human male sexuality

_02.jpg)

Human male sexuality covers physiological, psychological, social, cultural, and political aspects of the human male sexual response and related phenomena. It encompasses a broad range of topics involving male sexual desires and behavior that have also been addressed by ethics, morality, and religion.

Factors influencing male sexual behaviour

There are a number of factors that influence male sexuality and sexual behaviour, including expected parental investment, and paternal presence during development.

Expected paternal investment

Elizabeth Cashdan[1] proposed that mate strategies among both genders differ depending on how much parental investment is expected of the male, and provided research support for her hypotheses. When men expect to provide a high level of parental investment, they will attempt to attract women by emphasising their ability to invest. In addition, men who expect to invest will be more likely to highlight their chastity and fidelity than men who expect not to invest. Men with the expectation of low parental investment will flaunt their sexuality to women. The author argues the fact the research supports the idea that men expecting to invest emphasise their chastity and fidelity, which is a high cost strategy (because it lowers reproductive opportunities), suggests that that type of behaviour must be beneficial, or the behaviour would not have been selected.[1]

Early childhood experiences

A relationship between the early experiences and environment of boys, and their later sexual behaviour, has been drawn by several studies. Research suggests that father absence can lead to an increase in rape behaviour. Research conducted by Malamuth[2] found that men raised in the absence of their father (or where resources were scarce) reported more use of sexual coercion in the past, and were more likely to indicate being more willing to rape, in the event that there was no chance of them getting caught. Research has also found that parental divorce and rape correlate positively.[3]

Sociosexuality

Males who are in a committed relationship, in other words have a restricted sociosexual orientation, will have different sexual strategies compared to males who have an unrestricted sociosexual orientation. Males with a restricted sociosexual orientation will be less willing to have sex outside of their committed relationship, and adjust their strategies according to their desire for commitment and emotional closeness with their partner.

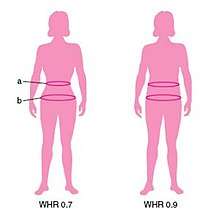

It has been found that such males are less likely to approach attractive females who have greater waist-to-hip ratios (0.68-0.72).[4]

Age of first sexual intercourse

One study has several factors that influence the age of first sexual intercourse among both genders. Those from families with both parents present, from high socioeconomic backgrounds, who performed better at school, were more religious, who had higher parental expectations, and felt like their parents care, showed lower levels of sexual activity across all age groups in the study (age 13-18). In contrast, those with higher levels of body pride, showed higher levels of sexual activity.[5]

Male sexually violent strategies

There are many sexual strategies that males can employ in order to gain mates. This includes sexual coercion.

Sexual coercion is forcing mate choice against a partner’s will or preference. Sexual coercion functions to increase the chance of a female mating with a male, and decrease the chance that the female will mate with another male.[6] There are several strategies by which sexual coercion can be achieved. These are harassment, intimidation, and forced copulation (rape).[7]

Evolutionary explanations

Thornhill and Palmer’s A Natural History of Rape investigates the evolutionary causes of sexual coercion, particularly of rape, and suggest that such behaviour is a result of sexual selection, rather than Darwinian natural selection.[8]

Of ten listed hypotheses, they accepted two reasonable hypotheses:

- The first, that rape is a by-product of an adaptation other than rape.

- The second, that rape as an adaptation (the rape specific adaptation hypothesis), which suggests that rape evolved because it was an adaptive, beneficial behaviour in the environment of evolutionary adaptation.

Thornhill and Palmer argue that these two theories are the strongest of the ten for several reasons. For example, both hypothesis argue rape exists because it functions to increase matings, thus improving reproductive success. Because rape can be a costly behaviour for the male - he risks injury inflicted by the victim, or punishment by her social allies, it must have strong reproductive benefits for the behaviour to survive and be demonstrated today. Thornhill and Palmer also use several facts to support the idea that the two evolutionary based hypotheses are the most reasonable. They argue that the fact that most rape victims are of childbearing age, that married women and women of childbearing age suffer more psychological distress after rape than single or post-menopausal women, and that rape takes place in a variety of other species, all point towards an evolutionary heritage for rape behaviour.[8]

Rape as an evolutionary by-product hypothesis

The 'rape as a by-product' explanation holds that rape behaviour evolved as a by-product of other psychological adaptations in men to obtain many mates.[8] This adaptation not only leads to rape but a number of other behaviours including overrating female sexual interest,[9] a desire for sexual variety, coercion, and sexual arousal which is not dependent on the consent of mate.[8][10]

Rape specific adaptation evolutionary hypothesis

The rape specific adaptation hypothesis suggests that rape is an evolved behaviour because it provides direct benefits to the rapist. In this case, the benefit would be a higher chance of reproductive success through increasing mate number. The hypothesis suggests that rape behaviour is the result of psychological mechanisms designed specifically to influence males to rape, unlike in the by-product hypothesis. This theory suggests that rape by a man which offers no chance of reproductive success, i.e. the rape of any other person who is not a female of reproductive age, is a maladaptive byproduct of this evolutionary adaptation.[8]

Support for the idea that rape provides males with a way to increase their reproductive success comes from a study by Barbaro and Shackelford, who found that men in committed heterosexual relationships who had committed at least one act of violence/coercion towards their partner in the last month had more in-pair copulations per week.[11]

Some potential specific psychological adaptations that Thornhill and Palmer suggest might be present in men to induce rape include the evolution of a mechanism that helps males evaluate the vulnerability of potential victims, or mechanism that motivates men with a lack of sexual access to females, to rape- the mate deprivation hypothesis.[8]

The mate deprivation hypothesis alludes to the concept that the threshold for rape is lowered in males that lack alternative reproductive options. This idea is supported by the fact that rape is disproportionately committed by men with a lower socioeconomic status.[12] However, Malamuth[2][13] found a relationship between low socioeconomic status and a rearing environment in which social relationships were not committed, which in turn resulted in a male’s reduced ability to form enduring relationships in later life. This subsequently results in less alternative reproductive options. Therefore, while there is indeed a relationship between a lack of alternative reproductive options and rape behaviour, there are likely to be a number of co-morbid factors affecting this correlation, leading Thornhill and Palmer to conclude that the idea of a specific psychological adaptation that motivated men with a lack of sexual access to females is unlikely, and that further research need be conducted.

Rejected hypotheses

One of Thornhill and Palmer's rejected hypotheses for why men rape implicates violent pornography. Subscribers to the social science theory of rape[14][15] purport that one of the main reasons why the human male learns to rape is via learning imitative behaviour when watching violent pornography. However, this fails to explain why if males are likely to imitate behaviour witnessed in violent pornography they would not also imitate the actions of human males in other videos. Furthermore, no explanation is offered into why this behaviour is inspired in some men and not others. It is also limited in its ability to predict valuable variables surrounding why rape occurs (such as who, when or where). For this reason, Thornhill and Palmer argued that "although the removal of violent pornography may be desirable in its own right, it is very unlikely to solve the problem of rape".[8]

Another of their rejected hypotheses is the 'choosing victim' rape-adaptation hypothesis which suggests that there is an evolved victim-preference mechanism to maximise the reproductive benefits of rape. This hypothesis suggests that men would be most likely to rape reproductive-age females. Research shows that the age of US rape victims correlates slightly better with age of peak fertility than age of peak reproductive potential.[12] However, this explanation does not explain the rape of those with no chance of reproductive success e.g. girls, boys, adult males, and post-menopausal women.

Development of sexual coercion

Though it is a widely held view that sexually coercive behaviour occurs as a result of sexual selection, Smuts and Smuts (1993) proposed that sexual coercion is best described as a third type of sexual selection, rather than attempting to fit it into either of the other two forms: mate choice and intrasex competition.[6] While sexual coercion certainly interacts with the other two forms of sexual selection, its conceptual distinction lies under the fact that a sexually coercive male may succeed in the competition for mates using coercion, despite losing in male-male competition for females, and despite not being chosen by females as a mate.

Male sexual entitlement

Coercive behaviour of men towards women can be argued to be a result of male sexual entitlement. Gender stereotypes view men and boys as being the more typically aggressive sex.[16] Subsequently, a man may act aggressively towards women and girls in order to increase his chances of submission from them. This is known as male sexual entitlement – the belief that women and girls owe men sex due to society viewing their sexual gratification as more important. This can result in men being more likely than women to view pressuring a woman or girl into sex as acceptable behavior.[17] Examples of men’s sexual entitlement include harassing women with thick breasts[18] and their refusal to perform oral sex on women.[19][20] Non-consensual condom removal has been described as "a threat to [a victim's] bodily agency and as a dignitary harm", and men who do this " justify their actions as a natural male instinct".[21]

Male sexual entitlement, which consequently can predict sexual entitlement due to societal norms, has been found to predict rape-related attitudes and behaviors.[22] If men feel that their own sexual needs are more important, it is likely that they will have rape-related attitudes, as such, attitudes reinforce their own sexual entitlement as being the more dominant sex.

Compromising sexual strategies

Sexual strategies are essential to males when pursuing a mate in order to maximize reproductive potential, in order for their genes to be passed on to future generations. However, in order for a male’s sexual strategy to succeed with a female, it is the male who must compromise his own sexual strategies, typically because of uncertainty over the paternity of a child, whereas maternity is essentially certain.

Women have higher levels of parental investment because they carry the developing child, and higher confidence in their maternity since they witness giving birth to the child. Hence women have reason to accept greater responsibility for raising their children. By comparison, males have no objective way of being certain that the child they are raising is biologically theirs. Because of this difference, males have to adapt their own sexual strategies to accommodate the strategies of the females around them.[23]

Among other behaviors, this means that men are more likely to favour chastity in a woman, as this way a male can be more certain that her offspring are his own. Such a strategy is seen in males, and maternity is never doubted by the female, and so a chaste male is not highly valued by women. However, for men, female chastity confirms paternity, causing the male to compromise his sexual strategies in order to select a chaste mate.

Male homoeroticism

Homoerotic behaviour differs from homosexuality (see below) in that it is purely same-sex sexual behaviour that occurs for pleasure, whereas homosexuality is the sexual orientation or enduring sexual preference for the same-sex.[24] Due to its universality, history and perceived functions it has been theorised that homoerotic behaviour has origins in evolution.[25]

History of male homoerotic behaviour

There is evidence of the long-standing existence of homoeroticism, dating back to early human history. From cave paintings of men engaging in sexual acts[26] to modern history, homoerotic behaviour is still prevalent today.

Evolutionary perspective

From an evolutionary perspective homoeroticism is seen as counter-productive as it doesn’t directly contribute to successfully producing offspring.[27] However, male-male sexual behaviour has been argued to have served an adaptive function and an indirect reproductive advantage for males. Evidence suggests that male-male sexual relations in early human periods often occurred between younger adolescent boys and older males. Sexual acts have been viewed as a psychological factor in societies used for bonding.[24] These same-sex relations between young adolescent boys and older men brought many benefits to the younger males, such as access to food, protection from aggression and overall helping them attain personal survival and an increased social standing. These direct effects on survival also led to indirect effects of reproductive success. The advantages the young males would obtain from their sexual relations with older men made them a more desired mating choice amongst females. The age and status difference between the men involved, suggests that a dominance-submission dynamic was an important factor in these relations.[24]

Alliance hypothesis

The Alliance theory perspective of male-male sexual behaviour in early humans states that this behaviour was a feature that developed to reduce aggression between different males and to enforce alliances.[28] It is believed that young adult males and adolescents were segregated from society and living on the outskirts of communities due to their perceived sexual threat by the older men. Therefore, same-sex behaviour allowed younger men to have reinforced alliances with other older males, which later gained them access to resources and females which were both scarce at the time.[24] Similarly, Kirkpatrick states male-male sexual behaviour has occurred in part because of the reciprocal-altruism hypothesis. The older male receives sexual gratification from the relationship whilst the younger male has to bear the cost of engaging in non-reproductve sex. However, the younger male is able to later receive the social benefits discussed, through this same-sex alliance. This relationship can be viewed as a resource exchange.[29]

In support of the evolutionary perspective, much of modern history demonstrates higher and lower status roles between two men involved in sexual relations.[24] There is evidence of males seducing each other for social gain as well as sexual pleasure. Examples of this in modern history include Roman Emperors such as Augustus Caesar, who supposedly acquired the throne in part due to their sexual relations with their predecessors.[30] Additionally, the ancient Greek custom of pederasty provides additional support for the evolutionary account. It was very common for adult males and adolescent males in ancient Greece to engage in sexual relations. Similarly to relationships found in early humans who displayed homoeroticism, the relationship dynamic between males involved in pederasty in the ancient Greek period was unequal. These young males also received benefits such as increased social networks and educational development.[31]

Functions of homoerotic behaviour

Homoerotic behaviour has been thought to be maintained by indirect selection, since it does not encourage reproduction. The kin-selection hypothesis, which argued that homosexuals contribute to their nephews’ and nieces’ survival, and the female fertility hypothesis, were both findings which support the idea that homoerotic behaviour is an evolutionary by-product that serves no beneficial function by itself (for discussion see the section on homosexuality, below).

Relatively newer studies suggest that similar to how heterosexual bonds provide non-conceptive benefits, including the maintenance of long-term bonds, homoerotic behaviour aid in same-sex alliances that help in resource competition or defense.[32] Emotions that are homosexual in nature could help to foster and reinforce supportive relationships, one example of which would be the Azande society[33] in which homosexual relationships were very common, and the Sambia, who engage in homoerotic behaviour between the initiates in their militia, and their behavior buttress bonds that were important in survival.[34]

In various societies, many individuals exhibit homoerotic behaviour during certain stages of their life, notably during adolescence, and generally before their heterosexual marriage, possibly because that same-sex alliances are more important in one’s early life than later, when the concern for sexual reproduction comes into play, and individuals who engage in homoerotic acts obtain benefits applicable to their reproductive lives. Before that period of their life, same-sex alliances are important in aiding survival, and among the Q'eqchi' of Belize, significantly more children survive past six months for men with same-sex alliance due to the increase in productivity of agricultural labour.

Same-sex alliances do not need to be sexual in nature, although when competition for partners is especially severe the sexualisation of same-sex alliances occurs more often.[32] Displays of commitment between partners are adaptive because of the cost in terms of efforts invested in maintaining the alliance.[35] Sex could be argued as a type of currency in long-term relationships, and signify to an individual’s partner and to others a prominent level of connection and commitment. Homosexual/homoerotic behaviour would be therefore a significant representation of one’s loyalty and affiliation in a same-sex alliance. Ultimately, homoerotic behaviour is not selectively disadvantaged, as homoerotic behaviour does not result in a net decrease to an individual’s reproductive success,[36] and the attraction to other individuals of same sex and the behaviour as result of that attraction is not contrary or alternative to the attraction to people of the other sex.[32]

Subsequent research in the role of homoerotic behaviour further supports the "affiliation hypothesis".[37][38][39] A study published in 2014 sought to measure homoerotic motivation, and to investigate how an affiliative context would affect homoerotic motivation in men, and found that men in an affiliative priming condition are more open to engaging in homoerotic behaviour. This effect is most pronounced in men with high progesterone, a hormone that is associated with affiliative motivation in humans. In spite of the opportunity costs homoerotic behaviour and motivation were thought to incur, the results provide data constituting evidence that homoerotic motivation, and subsequently homoerotic behaviour, holds the adaptive function of encouraging alliance formation and bonding.[40]

Sexual orientation

| Sexual orientation |

|---|

| Sexual orientations |

| Non-binary categories |

| Research |

| Non-human animals |

|

Male homosexuality

The Western "homosexual" category has been related to the non-Western "third gender" category, being cast as a redefinition and expansion of the latter category to include all biological males who acknowledge having same-sex attractions (instead of only effeminate males). This extension of "third gender" is due to various factors that were unique to the Western world, including the widespread influence of Christianity and the resultant encouragement of opposite-sex relationships. Before the concept of sexual orientation was developed in the modern West, only effeminate males who sought to be anally penetrated by men (oral sex was far less common than today) were seen as a belonging to a different gender category.[41] The Western equivalent of the third-genders (and not all men with same-sex attractions) were the ones who started and propagated the Western concept of a homosexual identity.[42][43][44][45]

Many non-Western societies show hostility towards the concept of homosexuality, which they view as a pernicious Western practice and a legacy of colonialism and (Western) sexual tourism. However, and strangely to Western eyes, such societies do accept both men who have sex with men and third-genders who have sex with men as an unremarkable part of society, so long as they're not called "homosexuals".

In the West, a man often cannot acknowledge or display sexual attraction for another man without the homosexual or bisexual label being attached to him.[46] The same pattern of shunning the homosexual identity, while still having sex with men, is prevalent in the non-West,[47][48] where sexual attraction between men is often seen as a universal male phenomenon—and practiced, either quietly or openly—even if held morally wrong in the larger society, sexual attraction between men being seen as a universal male quality, not something limited to a minority.[49][50][51]

Origins of the heterosexual–homosexual classification

In the 1860s, German third-gender Karl Heinrich Ulrichs coined a new term for third-genders that he called "urnings", which was supposed to mean "men who like men". These "urnings" were "females inside male bodies", who were emotionally or sexually attracted to men. Ulrichs and most self-declared members of the third sex thought that masculine men can never have sexual desires for other men. Hence, to be attracted to men, a male necessarily had to be feminine-gendered – had to have a female inside him. This was supported by Ulrichs' own experience, as well as by the fact that men only had sex with men secretively, due to the cultural climate. Ulrichs termed ordinary men (as opposed to third-genders) as "diones", meaning "men who like women."

Later, Austrian third-gender and human rights activist Karl Maria Kertbeny coined the terms "homosexual" and "heterosexual". For most of this period, these terms were popular only amongst the third-gender and scientific communities, the latter of which was developing the concept of homosexuality as a mental disorder.

Thus was born the idea of "men who like men" being different from "men who like women", and of differentiating male sexuality between "heterosexuality" and "homosexuality". The basis for the division, however, remained gender orientation (masculinity and femininity). Men who were now decidedly "heterosexual", however, rarely related to these terms; they saw themselves as neither heterosexual or homosexual. Even in 2010, "straight" men in the West, quite like men in the East,[52] seldom relate strongly to sexual identities.[53] These identities, however, remain a strong focus within the LGBT community.

See also

References

- 1 2 Cashdan, Elizabeth (1993). "Attracting mates: Effects of paternal investment on mate attraction strategies". Ethology and Sociobiology. 14: 1–23. doi:10.1016/0162-3095(93)90014-9.

- 1 2 "An evolutionary-based model integrating research on the characteristics of sexually coercive men". APA PsycNET. 1998-01-01.

- ↑ Starks, Philip T. (2000-06-22). "The relationship between serial monogamy and rape in the United States (1960–1995)". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 267 (1449): 1259–1263. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1136. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1690656. PMID 10902693.

- ↑ Brase, G.L.; Walker, G. (2004). "Male sexual strategies modify ratings of female models with specific waist-to-hip ratios". Human Nature. 15 (2): 209–224. doi:10.1007/s12110-004-1020-x.

- ↑ Lammers, Cristina; Ireland, Marjorie; Resnick, Michael; Blum, Robert (2000-01-01). "Influences on adolescents' decision to postpone onset of sexual intercourse: a survival analysis of virginity among youths aged 13 to 18 years". Journal of Adolescent Health. 26 (1): 42–48. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00041-5.

- 1 2 Smuts, B.B,; Smuts, R.W. (1993). "Male aggression and sexual coercion of females in nonhuman primates and other mammals: evidence and theoretical implications". Advances in the Study of Behaviour. 22: 1–63 – via researchgate.net.

- ↑ Clutton-Brock, T.H.; Parker, G.A. (1995). "Sexual coercion in animal societies". Animal Behaviour. 49 (5): 1345–1365. doi:10.1006/anbe.1995.0166 – via sciencedirect.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Thornhill, R; Palmer, C.T. (2001). A natural history of rape: Biological bases of sexual coercion. Cambridge, MA: Bradford Books.

- ↑ Henningsen, David Dryden; Henningsen, Mary Lynn Miller (2010-10-01). "Testing Error Management Theory: Exploring the Commitment Skepticism Bias and the Sexual Overperception Bias". Human Communication Research. 36 (4): 618–634. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01391.x. ISSN 1468-2958.

- ↑ Quinsey, Vernon L.; Chaplin, Terry C.; Upfold, Douglas (1984-08-01). "Sexual arousal to nonsexual violence and sadomasochistic themes among rapists and non-sex-offenders". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 52 (4): 651–657. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.52.4.651. ISSN 1939-2117.

- ↑ Barbaro, N; Shackleford, T.K. (2016). "Female-Directed Violence as a Form of Sexual Coercion in Humans (Homo sapiens)" (PDF). Journal of Comparative Psychology. 130 (4): 321. doi:10.1037/com0000038. PMID 27732014 – via researchgate.net.

- 1 2 Thornhill, Randy; Wilmsen Thornhill, Nancy (1983-01-01). "Human rape: An evolutionary analysis". Ethology and Sociobiology. 4 (3): 137–173. doi:10.1016/0162-3095(83)90027-4.

- ↑ "The confluence model of sexual aggression: Feminist and evolutionary perspectives". APA PsycNET. 1996-01-01.

- ↑ Denmark, Florence, L.; Friedman, Susan, B. (1985). "Social psychological aspects of rape". Violence against women: A critique of the sociobiology of rape.: 59–84.

- ↑ Stock, Wendy, E. (1991). "Feminist explanations: Male power, hostility and sexual coercion". Sexual coercion. 61: 73.

- ↑ Buss, A. H. (1961). The Psychology of Aggression. New York: Wiley.

- ↑ Margolin, L; Morgan, P. B.; Miller, M (1989). "Social approval for violations of sexual consent in marriage and dating". Violence and Victims. 4 (1): 45–55. PMID 2487126.

- ↑ Margolin, L; Morgan, P. B.; Miller, M (2013). "Men's Oppressive Beliefs Predict Their Breast Size Preferences in Women". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 42 (7): 1199–1207. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0081-5.

- ↑ Wood, Jessica; McKay, Alexander; Komarnicky, Tina; Komarnicky, Tin (2016). "An analysis of gender differences in oral sex practices and pleasure ratings among heterosexual Canadian university students". Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 25: 21–29. doi:10.3138/cjhs.251-A2.

- ↑ Lewis, Ruth; Marston, Cicely (2016). "Oral Sex, Young People, and Gendered Narratives of Reciprocity". The Journal of Sex Research. 53 (7): 776–787. doi:10.1080/00224499.2015.1117564.

- ↑ Brodsky, Alexandra, 'Rape-Adjacent': Imagining Legal Responses to Nonconsensual Condom Removal (2017) Columbia Journal of Gender and Law, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2017.SSRN 2954726

- ↑ Hill, M. S.; Fischer, A. R. (2001). "Does entitlement mediate the link between masculinity and rape-related variables?". Journal of Counselling Psychology. 48 (1): 39. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.48.1.39.

- ↑ MALE, S. P. C. (1995). Mate preference mechanisms: Consequences for partner choice and intrasexual competition. The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Muscarella, Frank (2000). "The evolution of homoerotic behaviour in humans". Journal of Homosexuality. 40 (40.1): 51–77. doi:10.1300/j082v40n01_03.

- ↑ Cosmides, Tooby (1992). "The psychological foundations of culture". The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture: 19–136.

- ↑ Ross, A (1973). "Celtic and northern art". Primitive Erotic Art: 77–106.

- ↑ Gallup, J (1983). "Homosexuaty as a By-Product of Selection for Optimal Heterosexual Strategies". Perspectives in biology and medicine. 26.2 (2): 315–322. doi:10.1353/pbm.1983.0018.

- ↑ Muscarella, Frank (2007). "The evolution of male-male sexual behaviour in humans: The alliance theory". Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 18.4 (4): 275–311. doi:10.1300/j056v18n04_02.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, C (2000). "The evolution of human homosexual behaviour". Current Anthropology. 41.3 (3): 385–413. doi:10.1086/300145.

- ↑ Boswell, John (1980). "Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century".

- ↑ Ungaretti, John (1978). "Pederasty, heroism and the family in classical Greece". Journal of Homosexuality. 3 (3): 291–300. doi:10.1300/j082v03n03_11. PMID 351049.

- 1 2 3 Kirkpatrick, R. C. (2000-01-01). "The Evolution of Human Homosexual Behavior". Current Anthropology. 41 (3): 385–413. doi:10.1086/300145. JSTOR 10.1086/300145. PMID 10768881.

- ↑ Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1970-12-01). "Sexual Inversion among the Azande". American Anthropologist. 72 (6): 1428–1434. doi:10.1525/aa.1970.72.6.02a00170. ISSN 1548-1433.

- ↑ Herdt, Gilbert H. (1993-01-01). Ritualized Homosexuality in Melanesia. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520080966.

- ↑ Zahavi, Amotz (1975-09-01). "Mate selection—A selection for a handicap". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 53 (1): 205–214. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(75)90111-3.

- ↑ Weinrich, James D (1987-01-01). "A new sociobiological theory of homosexuality applicable to societies with universal marriage". Ethology and Sociobiology. 8 (1): 37–47. doi:10.1016/0162-3095(87)90056-2.

- ↑ Bowles, Samuel (2009-06-05). "Did Warfare Among Ancestral Hunter-Gatherers Affect the Evolution of Human Social Behaviors?". Science. 324 (5932): 1293–1298. doi:10.1126/science.1168112. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19498163.

- ↑ Hill, Kim; Hurtado, A. Magdalena (2009-08-19). "Cooperative breeding in South American hunter–gatherers". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1674): 3863–70. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1061. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2817285. PMID 19692401.

- ↑ Sugiyama, Lawrence S. (2004-04-01). "Illness, injury, and disability among Shiwiar forager-horticulturalists: Implications of health-risk buffering for the evolution of human life history". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 123 (4): 371–389. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10325. ISSN 1096-8644.

- ↑ Fleischman, Diana S.; Fessler, Daniel M. T.; Cholakians, Argine Evelyn (2014-11-25). "Testing the Affiliation Hypothesis of Homoerotic Motivation in Humans: The Effects of Progesterone and Priming". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 44 (5): 1395–1404. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0436-6. ISSN 0004-0002.

- ↑ Zuni Berdache Archived 8 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Quotes: History of hermaphrodites

- ↑ A false birth: A critique of social constructionism and postmodern queer theory, by Rictor Norton

- ↑ Sex and the Gender Revolution, Volume 1 Heterosexuality and the Third Gender in Enlightenment London Quotes: The University of Chicago Press, by Randolph Trumbach

- ↑ Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Alfred C. Kinsey, Wardell R. Pomeroy and Clyde E. Martin Quote: "Males do not represent two discrete populations, heterosexual and homosexual. The world is not to be divided into sheep and goats. Not all things are black nor all things white."

- ↑ A false birth Quote: "... It is argued that 'Whitman himself stubbornly resisted the notion of a distinctive homosexual sensibility' (D'Emilio 1993)"

- ↑ 'I want to do what I want to do': young adults resisting sexual identities Fiona J. Stewart, Anton Mischewski, Anthony M. A. Smith; Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. Quote: "I don't think I was actually afraid of being gay, what I was afraid of was having a gay identity imposed upon me without my control over it..."

- ↑ Prevalence of Same-Sex Sexual Behavior and Associated Characteristics among Low-Income Urban Males in Peru, PLoS ONE,"Researchers studying same-sex sexual contact and related risk behaviors among Latino men have described a construction of sexuality that links penetration with masculinity and receptive intercourse with femininity, through which male same-sex sexual contact does not necessarily presume a homosexual identity."

- ↑ Straight Men Who Have Sex With Men by Tristan Taormino, The Village Voice.

- ↑ Edward J. Tejirian (17 October 2000). Amazon.com: Male to Male: Sexual Feeling Across the Boundaries of Identity (Haworth Gay & Lesbian Studies). amazon.com. ISBN 9781560239758.

- ↑ Afghan Men Struggle With Sexual Identity, Study Finds Fox News

- ↑ In order to understand the origins of male sexuality, a variety of demographics need to be researched, including race. According to Zea (2003), "to study sexual attitude, identities, and behaviors of Latino gay and bisexual men, it is necessary to understand the role of culture"(p.282).

- ↑ Sexuality and Society Fox News Struggles with Sexual Identities of Afghan Men by Shari L. Dworkin; Sexuality and Society; Quote from the report: "found that Pashtun men commonly have sex with other men, admire other men physically, have sexual relationships with boys and shun women both socially and sexually – yet they completely reject the label of 'homosexual'."

- ↑ of sexual identity formation in heterosexual students, SpringerLink; by Michele J. Eliason1, College of Nursing, The University of Iowa; Quote from the abstract: Students could be categorized into all four of Marcia's identity statuses. Additionally, six common themes were noted in their essays: had never thought about sexual identity; society made me heterosexual; gender determines sexual identity; issues of choice versus innateness of sexuality; no alternative to heterosexuality; and the influence of religion.