Gray asexuality

| Sexual orientation |

|---|

| Sexual orientations |

| Non-binary categories |

| Research |

| Non-human animals |

|

Gray asexuality or gray-sexuality (spelled "grey" outside the U.S.) is the spectrum between asexuality and sexuality.[1] Individuals who identify with gray asexuality are referred to as being gray-A, a grace or a gray ace, and make up what is referred to as the "ace umbrella".[2] Within this spectrum are terms such as demisexual, semisexual, asexual-ish and sexual-ish.[3]

Those who identify as gray-A tend to lean towards the more asexual side of the aforementioned spectrum.[4] As such, the emergence of online communities, such as the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN), have given gray aces locations to discuss their orientation.[1][4]

Definitions

General

Gray asexuality is considered the gray area between asexuality and sexuality, in which a person may only experience sexual attraction on occasion.[1] The term demisexuality was coined in 2008 by Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN).[2] The prefix "demi" derives from the Latin dimidium meaning "divided in half". The term demisexual comes from the concept being described as being "halfway between" sexual and asexual. The term does not mean that demisexuals have an incomplete or half-sexuality; nor does it mean that sexual attraction without emotional connection is required for a complete sexuality.[5]

The term gray-A covers a range of identities under the asexuality umbrella, or on the asexual spectrum, including demisexuality.[6] Other terms within this spectrum include semisexual, asexual-ish and sexual-ish.[3] The gray-A spectrum usually includes individuals who "experience sexual attraction very rarely, only under specific circumstances, or of an intensity so low that it's ignorable".[7] Sari Locker, a sexuality educator at Teachers College of Columbia University, argued during a Mic interview that gray-asexuals "feel they are within the gray area between asexuality and more typical sexual interest".[8]

Demisexuality

Demisexuality refers to those who "may experience secondary sexual attraction after a close emotional connection has already formed".[9] The Demisexual Resource Center says that "Demisexuals are considered part of the asexual community because for the most part, they don’t feel sexual attraction. Many demisexuals are only attracted to a handful of people in their lifetimes, or even just one person. Many demisexuals are also uninterested in sex, so they have a lot in common with asexuals."[10] Demisexuality is different for different people because of several reasons, one of the first and foremost being that the definition of "emotional bond" varies from person to person.[11] Another reason it varies is because people in the asexual spectrum communities often switch labels throughout their lives, and fluidity in orientation and identity is a common attitude.[2] Demisexuals can have any romantic orientation, including being aromantic (romantic attraction to no genders), gray-aromantic (the area between being aromantic and feeling romantic attraction), demiromantic (not feeling romantic attraction until an emotional bond is formed) – they can also be heteroromantic, homoromantic, biromantic, panromantic, or polyromantic.[12]

Demisexuality or general sexuality wherein it is interlaced with an emotional connection is a common theme in romantic novels and has been termed with a coinage compulsory demisexuality.[13] Within fictitious prose, the paradigm of sex being only truly pleasurable when the partners are in love is a trait stereotypically more commonly associated with female characters. The intimacy of the connection also allows for an exclusivity to take place.[14] Demisexuals have received visibility through being hosted on some proposed asexual flags.[15] Unlike other asexuals, demisexuals do not necessarily lack a libido.[16][17] Demisexuality has been compared with heavy metal fandom due to much of its lyrics hinging upon the necessity of a romantic attraction.[18] Another description of demisexual describes it as "ensuing from romantic attraction".[19] It has been theorized as an inclination deriving from a need for trustworthiness in one's partner.[20]

Romantic orientation

The romantic orientation of a gray-A identifying individual can vary, because sexual and romantic identities are not necessarily linked.[9] While some are aromantic, others are heteroromantic, homoromantic, biromantic, or panromantic, and regardless of romantic orientation, are able to develop intimate relationships with other individuals.[2][3]

Community

A Wired article notes examples of fluidity in the asexual and gray-A spectrum being accepted within the asexual community.[2] A Huffington Post article quotes a gray-A-identifying high school student saying, "Sexuality is so fluid, and Gray-A presents more of a possibility to be unsure."[3]

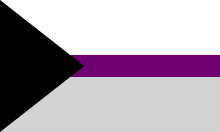

The AVEN, as well as blogging websites such as Tumblr, have given ways for gray-As to find acceptance in their communities.[7] While gray-As are noted to have variety in the experiences of sexual attraction, individuals in the community share their identification within the spectrum.[21] A black, gray, white, and purple flag is commonly used to display pride in the asexual community. The gray bar represents the area of gray sexuality within the community.[22]

Research

Asexuality in general is relatively new to academic research and public discourse.[23][24]

References

- 1 2 3 Bogaert, Anthony F. (2015-01-04). Understanding Asexuality. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442201002.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McGowan, Kat (February 18, 2015). "Young, Attractive, and Totally Not Into Having Sex". Wired. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Mosbergen, Dominique (June 19, 2013). "The Asexual Spectrum: Identities In The Ace Community (INFOGRAPHIC)". Huffington Post. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- 1 2 White, Rachel (November 22, 2011). "What It Means To Be "Gray-Sexual"". The Frisky. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ↑ Nurdina, Ovira (2017). "The linguistic forms of English sexual euphemistic expressions in Lady Chatterley's Lovers". Journal of Language and Literature. 1 (5).

- ↑ Weinberg, Thomas S.; Newmahr, Staci (2014-03-06). Selves, Symbols, and Sexualities: An Interactionist Anthology. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781483323893.

- 1 2 Shoemaker, Dale (February 13, 2015). "No Sex, No Love: Exploring asexuality, aromanticism at Pitt". The Pitt News. Archived from the original on February 17, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ↑ Zeilinger, Julie (May 1, 2015). "6 Actual Facts About What It Really Means to Be Asexual". Mic. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- 1 2 "Asexuality, Attraction, and Romantic Orientation". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ↑ "What is Demisexuality? | Demisexuality Resource Center". demisexuality.org. Archived from the original on 2016-12-11. Retrieved 2016-12-15.

- ↑ "Bustle". www.bustle.com. Retrieved 2016-12-16.

- ↑ "What Does It Mean To Be Demisexual And Demiromantic? - HelloFlo". HelloFlo. 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2016-12-16.

- ↑ McAlister, Jodi. "First Love, Last Love, True Love: Heroines, Heroes, and the Gendered Representation of Love in the Category Romance Novel." Gender & Love, 3rd Global Conference. Mansfield College, Oxford, UK. Vol. 15. 2013

- ↑ McAlister, Jodi (1 September 2014). "'That complete fusion of spirit as well as body': Heroines, heroes, desire and compulsory demisexuality in the Harlequin Mills & Boon romance novel". Australasian Journal of Popular Culture. 3 (3): 299–310. doi:10.1386/ajpc.3.3.299_1 – via IngentaConnect.

- ↑ Helen Andersen; Heather Bryant (May 3, 2016). "Building the House of Cards: The Role of the Internet in the Growth of the Asexual Community" (PDF). Wellesley.edu. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ Zimmer, Benjamin, Jane Solomon, and Charles E. Carson. "Among the new words." American Speech 89.4 (2014): 470-496

- ↑ "Asexuality, Attraction, and Romantic Orientation | LGBTQ". lgbtq.unc.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-25.

- ↑ Hoad, Catherine. "Slashing through the boundaries: Heavy metal fandom, fan fiction and girl cultures." Metal Music Studies 3.1 (2017): 5-22.

- ↑ Carrigan, Mark. "The history of asexuality." The Palgrave Handbook of the Psychology of Sexuality and Gender (2015): 7

- ↑ Witherspoon, Ryan G. "Multicultural and Diversity." Independent Practitioner: 70

- ↑ Cerankowski, Karli June; Milks, Megan (2014-03-14). Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 9781134692538.

- ↑ Williams, Isabel. "Introduction to Asexual Identities & Resource Guide". Campus Pride. Archived from the original on August 26, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Stark, Leah (February 23, 2015). "Stanford scholar blazes pathway for academic study of asexuality". Stanford News. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Smith, SE (August 21, 2012). "Asexuality always existed, you just didn't notice it". The Guardian. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

Bibliography

- Bogaert, Anthony F. (2012). Understanding Asexuality. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1442200999. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- Cerankowski, Karli June; Milks, Megan (2014). Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-71442-6. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- Weinberg, Thomas S.; Newmahr, Staci D. (2015). Selves, Symbols, and Sexualities: An Interactionist Anthology. SAGE Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4522-7665-6. Retrieved March 4, 2015.