Cinema of South Korea

| Cinema of South Korea | |

|---|---|

A movie theater in Seoul. | |

| No. of screens | 2,492 (2015)[1] |

| • Per capita | 5.3 per 100,000 (2015)[1] |

| Main distributors |

CJ E&M (21%) NEW (18%) Lotte (15%)[2] |

| Produced feature films (2015)[3] | |

| Total | 269 |

| Number of admissions (2015)[4] | |

| Total | 217,300,000 |

| National films | 113,430,600 (52%) |

| Gross box office (2015)[4] | |

| Total | ₩1.59 trillion |

| National films | ₩830 billion (52%) |

The cinema of South Korea refers to the film industry of South Korea from 1945 to present. South Korean films have been heavily influenced by such events and forces as the Japanese occupation of Korea, the Korean War, government censorship, business sector, globalization, and the democratization of South Korea.[5][6][7][8]

The golden age of South Korean cinema in the mid-20th century produced what are considered two of the best South Korean films of all time, The Housemaid (1960) and Obaltan (1961),[9] while the 2010s produced the country's highest-grossing films, including The Admiral: Roaring Currents (2014) and Along with the Gods: The Two Worlds (2017).[10]

South Korean films that have received widespread international attention and accolades include the cult hit Oldboy (2003)[11] and the English-language film Snowpiercer (2013).[12]

History

Liberation and war (1945-1953)

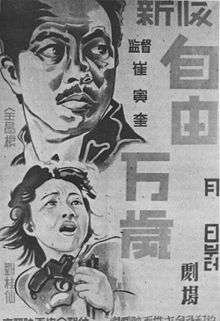

With the surrender of Japan in 1945 and the subsequent liberation of Korea, freedom became the predominant theme in South Korean cinema in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[5] One of the most significant films from this era is director Choi In-gyu's Viva Freedom! (1946), which is notable for depicting the Korean independence movement. The film was a major commercial success because it tapped into the public's excitement about the country's recent liberation.[13]

However, during the Korean War, the South Korean film industry stagnated, and only 14 films were produced from 1950 to 1953. All of the films from that era have since been lost.[14] Following the Korean War armistice in 1953, South Korean president Syngman Rhee attempted to rejuvenate the film industry by exempting it from taxation. Additionally foreign aid arrived in the country after the war that provided South Korean filmmakers with equipment and technology to begin producing more films.[15]

Golden age (1955-1972)

.jpg)

Though filmmakers were still subject to government censorship, South Korea experienced a golden age of cinema, mostly consisting of melodramas, starting in the mid-1950s.[5] The number of films made in South Korea increased from only 15 in 1954 to 111 in 1959.[16]

One of the most popular films of the era, director Lee Kyu-hwan's now lost remake of Chunhyang-jeon (1955), drew 10 percent of Seoul's population to movie theaters[15] However, while Chunhyang-jeon re-told a traditional Korean story, another popular film of the era, Han Hyung-mo's Madame Freedom (1956), told a modern story about female sexuality and Western values.[17]

South Korean filmmakers enjoyed a brief freedom from censorship in the early 1960s, between the administrations of Syngman Rhee and Park Chung-hee.[18] Kim Ki-young's The Housemaid (1960) and Yu Hyun-mok's Obaltan (1961), now considered among the best South Korean films ever made, were produced during this time.[9] Kang Dae-jin's The Coachman (1961) became the first South Korean film to win an award at an international film festival when it took home the Silver Bear Jury Prize at the 1961 Berlin International Film Festival.[19][20]

When Park Chung-hee became acting president in 1962, government control over the film industry increased substantially. Under the Motion Picture Law of 1962, a series of increasingly restrictive measures was enacted that limited imported films under a quota system. The new regulations also reduced the number of domestic film-production companies from 71 to 16 within a year. Government censorship targeted obscenity, communism, and unpatriotic themes in films.[21][22]

Nonetheless, the Motion Picture Law's limit on imported films resulted in a boom of domestic films. South Korean filmmakers had to work quickly to meet public demand, and many films were shot in only a few weeks. During the 1960s, the most popular South Korean filmmakers released six to eight films per year. Notably, director Kim Soo-yong released ten films in 1967, including Mist, which is considered to be his greatest work.[19]

In 1967, South Korea's first animated feature film, Hong Kil-dong, was released. A handful of animated films followed including Golden Iron Man (1968), South Korea's first science-fiction animated film.[19]

Censorship and propaganda (1973–1979)

Government control of South Korea's film industry reached its height during the 1970s under President Park Chung-hee's authoritarian "Yusin System." The Korean Motion Picture Promotion Corporation was created in 1973, ostensibly to support and promote the South Korean film industry, but its primary purpose was to control the film industry and promote "politically correct" support for censorship and government ideals.[23] According to the 1981 International Film Guide, "No country has a stricter code of film censorship than South Korea – with the possible exception of the North Koreans and some other Communist bloc countries."[24]

Only filmmakers who had previously produced "ideologically sound" films and who were considered to be loyal to the government were allowed to release new films. Members of the film industry who tried to bypass censorship laws were blacklisted and sometimes imprisoned.[25] One such blacklisted filmmaker, the prolific director Shin Sang-ok, was kidnapped by the North Korean government in 1978 after the South Korean government revoked his film-making license in 1975.[26]

The propaganda-laden movies (or "policy films") produced in the 1970s were unpopular with audiences who had become accustomed to seeing real-life social issues onscreen during the 1950s and 1960s. In addition to government interference, South Korean filmmakers began losing their audience to television, and movie-theater attendance dropped by over 60 percent from 1969 to 1979.[27]

Films that were popular among audiences during this era include Yeong-ja's Heydays (1975) and Winter Woman (1977), both box office hits directed by Kim Ho-sun.[26] Yeong-ja's Heydays and Winter Women are classified as "hostess films," which are movies about prostitutes and bargirls. Despite their overt sexual content, the government allowed the films to be released, and the genre was extremely popular during the 1970s and 1980s.[22]

Recovery (1980–1996)

In the 1980s, the South Korean government began to relax its censorship and control of the film industry. The Motion Picture Law of 1984 allowed independent filmmakers to begin producing films, and the 1986 revision of the law allowed more films to be imported into South Korea.[21]

Meanwhile, South Korean films began reaching international audiences for the first time in a significant way. Director Im Kwon-taek's Mandala (1981) won the Grand Prix at the 1981 Hawaii Film Festival, and he soon became the first Korean director in years to have his films screened at European film festivals. His film Gilsoddeum (1986) was shown at the 36th Berlin International Film Festival, and actress Kang Soo-yeon won Best Actress at the 1987 Venice International Film Festival for her role in Im's film, The Surrogate Woman.[28]

In 1988, the South Korean government lifted all restrictions on foreign films, and American film companies began to set up offices in South Korea. In order for domestic films to compete, the government once again enforced a screen quota that required movie theaters to show domestic films for at least 146 days per year. However, despite the quota, the market share of domestic films was only 16 percent by 1993.[21]

The South Korean film industry was once again changed in 1992 with Kim Ui-seok's hit film Marriage Story, released by Samsung. It was the first South Korean movie to be released by business conglomerate known as a chaebol, and it paved the way for other electronics chaebols to enter the film industry, using an integrated system of financing, producing, and distributing films.[29]

Renaissance (1997–present)

As a result of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, many chaebols began to scale back their involvement in the film industry. However, they had already laid the groundwork for a renaissance in South Korean film-making by supporting young directors and introducing good business practices into the industry.[29] "New Korean Cinema," including glossy blockbusters and creative genre films, began to emerge in the late 1990s and 2000s.[6]

One of the first blockbusters was Kang Je-gyu's Shiri (1999), a film about a North Korean spy in Seoul. It was the first film in South Korean history to sell more than two million tickets in Seoul alone.[30] Shiri was followed by other blockbusters including Park Chan-wook's Joint Security Area (2000), Kwak Jae-yong's My Sassy Girl (2001), Kwak Kyung-taek's Friend (2001), Kang Woo-suk's Silmido (2003), and Kang Je-gyu's Taegukgi (2004), all of which were more popular with South Korean audiences than Hollywood films of the era. For example, both Silmido and Taegukgi were seen by 10 million people domestically–about one-quarter of South Korea's entire population.[31]

South Korean films began attracting significant international attention in the 2000s, due in part to filmmaker Park Chan-wook, whose movie Oldboy (2003) won the Grand Prix at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival and was praised by American directors including Quentin Tarantino and Spike Lee, the latter of whom remade Oldboy in 2013.[11][32]

Director Bong Joon-ho's The Host (2006) and later the English-language film Snowpiercer (2013), are among the highest grossing films of all time in South Korea and were praised by foreign film critics.[33][12][34] Yeon Sang-ho's Train to Busan (2016), also one of the highest grossing films of all time in South Korea, became the second highest grossing film in Hong Kong in 2016.[35]

Highest-grossing films

The Korean Film Council has published box office data on South Korean films since 2004. As of July 2018, the top ten highest-grossing domestic films in South Korea since 2004 are as follows.[33]

- The Admiral: Roaring Currents (2014)

- Along with the Gods: The Two Worlds (2017)

- Ode to My Father (2014)

- Veteran (2015)

- The Thieves (2012)

- Miracle in Cell No.7 (2013)

- Assassination (2015)

- Masquerade (2012)

- A Taxi Driver (2017)

- Train to Busan (2016)

Film awards

South Korea's first film awards ceremonies were established in the 1950s, but have since been discontinued. The longest-running and most popular film awards ceremonies are the Grand Bell Awards, which were established in 1962, and the Blue Dragon Film Awards, which were established in 1963. Other awards ceremonies include the Baeksang Arts Awards, the Korean Association of Film Critics Awards, and the Busan Film Critics Awards.[36]

Film festivals

In South Korea

Founded in 1996, the Busan International Film Festival is South Korea's major film festival and has grown to become one of the largest and most prestigious film events in Asia.[37]

South Korea at international festivals

The first South Korean film to win an award at an international film festival was Kang Dae-jin's The Coachman (1961), which was awarded the Silver Bear Jury Prize at the 1961 Berlin International Film Festival.[19][20] The tables below list South Korean films that have since won major international film festival prizes.

Berlin International Film Festival

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[38] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Silver Bear Jury Prize | The Coachman | Kang Dae-jin |

| 1962 | To the Last Day | Shin Sang-ok | |

| 1964 | Alfred Bauer Prize | Hwa-Om-Kyung | Jang Sun-woo |

| 2004 | Silver Bear for Best Director | Samaritan Girl | Kim Ki-duk |

| 2005 | Honorary Golden Bear | N/A | Im Kwon-taek |

| 2007 | Alfred Bauer Prize | I'm a Cyborg, But That's OK | Park Chan-wook |

| 2011 | Golden Bear for Best Short Film | Night Fishing | Park Chan-wook, Park Chan-kyong |

| Silver Bear for Best Short Film | Broken Night | Yang Hyo-joo | |

| 2017 | Silver Bear for Best Actress | On the Beach at Night Alone | Kim Min-hee |

Cannes Film Festival

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[39] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Best Director | Chi-hwa-seon | Im Kwon-taek |

| 2004 | Grand Prix | Oldboy | Park Chan-wook |

| 2007 | Best Actress | Secret Sunshine | Jeon Do-yeon |

| 2009 | Prix du Jury | Thirst | Park Chan-wook |

| 2010 | Best Screenplay Award | Poetry | Lee Chang-dong |

| Prix Un Certain Regard | Hahaha | Hong Sang-soo | |

| 2011 | Arirang | Kim Ki-duk | |

| 2013 | Short Film Palme d'Or | Safe | Moon Byoung-gon |

Locarno Festival

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[40] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | Golden Leopard | Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? | Bae Yong-kyun |

| 2013 | Best Direction Award | Our Sunhi | Hong Sang-soo |

| 2015 | Golden Leopard | Right Now, Wrong Then |

Venice Film Festival

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[41] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Best Actress | The Surrogate Woman | Kang Soo-yeon |

| 2002 | Silver Lion | Oasis | Lee Chang-dong |

| 2004 | 3-Iron | Kim Ki-duk | |

| 2012 | Golden Lion | Pietà |

Tokyo International Film Festival

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[42] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | FIPRESCI Prize | The Man with Three Coffins | Lee Jang-ho |

| 1992 | Grand Prix | White Badge | Chung Ji-young |

| Best Director | |||

| 1998 | Gold Award | Spring in My Hometown | Lee Kwang-mo |

| 1999 | Special Jury Prize | Rainbow Trout | Park Jong-won |

| 2000 | Special Jury Prize | Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors | Hong Sang-soo |

| Asian Film Award - Special Mention | |||

| 2001 | Best Artistic Contribution Award | One Fine Spring Day | Hur Jin-ho |

| 2003 | Asian Film Award | Memories of Murder | Bong Joon-ho |

| Asian Film Award - Special Mention | Jealousy Is My Middle Name | Park Chan-ok | |

| 2004 | Best Director | The President's Barber | Im Chan-sang |

| Audience Award | |||

| Asian Film Award | Possible Changes | Min Byeong-guk | |

| Asian Film Award - Special Mention | Springtime | Ryu Jang-ha | |

| 2009 | Asian Film Award | A Brand New Life | Ounie Lecomte |

| 2012 | Special Jury Prize | Juvenile Offender | Kang Yi-Kwan |

| Best Actor | Seo Young-Joo | ||

| 2013 | Audience Award | Red Family | Lee Ju-hyoung |

See also

References

- 1 2 "Table 8: Cinema Infrastructure - Capacity". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ↑ "Table 6: Share of Top 3 distributors (Excel)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ↑ "Table 1: Feature Film Production - Method of Shooting". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- 1 2 "Table 11: Exhibition - Admissions & Gross Box Office (GBO)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- 1 2 3 Stamatovich, Clinton (2014-10-25). "A Brief History of Korean Cinema, Part One: South Korea by Era". Haps Korea Magazine. Retrieved 2017-02-15.

- 1 2 Paquet, Darcy (2012). New Korean Cinema: Breaking the Waves. Columbia University Press. pp. 1–5. ISBN 0231850123. .

- ↑ Messerlin, P.A. and Parc, J. 2017, The Real Impact of Subsidies on the Film Industry (1970s–Present): Lessons from France and Korea, Pacific Affairs 90(1): 51-75.

- ↑ Parc, J. 2017, The Effects of Protection in Cultural Industries: The Case of the Korean Film Policies, The International Journal of Cultural Policy 23(5): 618-633

- 1 2 Min, p.46.

- ↑ Jin, Min-ji (2018-02-13). "Third 'Detective K' movie tops the local box office". Korea JoongAng Daily. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- 1 2 Chee, Alexander (2017-10-16). "Park Chan-wook, the Man Who Put Korean Cinema on the Map". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- 1 2 Nayman, Adam (2017-06-27). "Bong Joon-ho Could Be the New Steven Spielberg". The Ringer. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- ↑ "Viva Freedom! (Jayumanse) (1946)". Korean Film Archive. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- ↑ Gwon, Yeong-taek (2013-08-10). "한국전쟁 중 제작된 영화의 실체를 마주하다" [Facing the reality of film produced during the Korean War]. Korean Film Archive (in Korean). Archived from the original on 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- 1 2 Paquet, Darcy (2007-03-01). "A Short History of Korean Film". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- ↑ Paquet, Darcy. "1945 to 1959". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- ↑ McHugh, Kathleen; Abelmann, Nancy, eds. (2005). South Korean Golden Age Melodrama: Gender, Genre, and National Cinema. Wayne State University Press. pp. 25–38. ISBN 0814332536.

- ↑ Goldstein, Rich (2014-12-30). "Propaganda, Protest, and Poisonous Vipers: The Cinema War in Korea". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2017-02-15.

- 1 2 3 4 Paquet, Darcy. "1960s". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- 1 2 "Prizes & Honours 1961". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- 1 2 3 Rousse-Marquet, Jennifer (2013-07-10). "The Unique Story of the South Korean Film Industry". French National Audiovisual Institute (INA). Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- 1 2 Kim, Molly Hyo (2016). "Film Censorship Policy During Park Chung Hee's Military Regime (1960-1979) and Hostess Films" (PDF). IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies. 1: 33–46. doi:10.22492/ijcs.1.2.03 – via wp-content.

- ↑ Gateward, Frances (2012). "Korean Cinema after Liberation: Production, Industry, and Regulatory Trend". Seoul Searching: Culture and Identity in Contemporary Korean Cinema. SUNY Press. p. 18. ISBN 0791479331.

- ↑ Kai Hong, "Korea (South)", International Film Guide 1981, p.214. quoted in Armes, Roy (1987). "East and Southeast Asia". Third World Film Making and the West. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 156. ISBN 0-520-05690-6.

- ↑ Taylor-Jones, Kate (2013). Rising Sun, Divided Land: Japanese and South Korean Filmmakers. Columbia University Press. p. 28. ISBN 0231165854.

- 1 2 Paquet, Darcy. "1970s". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- ↑ Min, p.51-52.

- ↑ Hartzell, Adam (March 2005). "A Review of Im Kwon-Taek: The Making of a Korean National Cinema". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- 1 2 Chua, Beng Huat; Iwabuchi, Koichi, eds. (2008). East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 16–22. ISBN 9622098924.

- ↑ Artz, Lee; Kamalipour, Yahya R., eds. (2007). The Media Globe: Trends in International Mass Media. New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 978-0742540934.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Scott (2004-12-01). "Thinking Outside the Box". Film Journal International. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ↑ Lee, Hyo-won (2013-11-18). "Original 'Oldboy' Gets Remastered, Rescreened for 10th Anniversary in South Korea". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- 1 2 "Box Office: All Time". Korean Film Council. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ Pomerantz, Dorothy (2014-09-08). "What The Economics Of 'Snowpiercer' Say About The Future Of Film". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ Kang Kim, Hye Won (2018-01-11). "Could K-Film Ever Be As Popular As K-Pop In Asia?". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ Paquet, Darcy. "Film Awards Ceremonies in Korea". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ Steger, Isabella (2017-10-10). "South Korea's Busan film festival is emerging from under a dark political cloud". Quartz. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ "Prizes & Honours". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ "Cannes Film Festival". IMDb. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ "Locarno International Film Festival". IMDb. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ "History of Biennale Cinema". La Biennale di Venezia. 2017-12-07. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ "Tokyo International Film Festival". IMDb. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- Bowyer, Justin (2004). The Cinema of Japan and Korea. London: Wallflower Press. ISBN 1-904764-11-8.

- Min, Eungjun; Joo Jinsook; Kwak HanJu (2003). Korean Film : History, Resistance, and Democratic Imagination. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-95811-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cinema of South Korea. |