Baiyue

| Baiyue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Statue of a man, from the state of Yue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 百越 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Bách Việt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | Bakyez | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Baiyue, Hundred Yue or Yue were various indigenous non-Chinese peoples who inhabited the region stretching along the coastal area from Shandong to southeast China, and as far west as the Sichuan Basin between the first millennium BC and the first millennium AD.[1] Meacham (1996:93) notes that, during the Zhou and Han dynasties, the Yue lived in a vast territory from Jiangsu to Yunnan,[2] while Barlow (1997:2) indicates that the Luoyue occupied the southwest Guangxi and north Vietnam.[3] The Han shu (漢書) describes the lands of Yue as stretching from the regions of Kuaiji (會稽) to Jiaozhi (交趾).[4] In the Warring States period, the word "Yue" referred to the State of Yue in Zhejiang. The later kingdoms of Minyue in Fujian and Nanyue in Guangdong were both considered Yue states.

The Yue tribes were gradually displaced or assimilated into Chinese culture as the Han empire expanded into what is now Southern China and Northern Vietnam during the first half of the first millennium AD. Many modern southern Chinese dialects bear traces of substrate languages originally spoken by the ancient Yue. Variations of the name are still used for the name of modern Vietnam, in Zhejiang-related names including Yue Opera, th Yue Chinese language, and in the abbreviation for Guangdong.

Names

The modern term "Yue" (Chinese: 越 or 粵; pinyin: Yuè; Cantonese Yale: Yuht; Wade–Giles: Yüeh4; Vietnamese: Việt; Zhuang: Vot; Early Middle Chinese: Wuat) comes from Old Chinese *ɢʷat (William H. Baxter and Laurent Sagart 2014).[5] It was first written using the pictograph "戉" for an axe (a homophone), in oracle bone and bronze inscriptions of the late Shang dynasty (c. 1200 BC), and later as "越".[6] At that time it referred to a people or chieftain to the northwest of the Shang.[2] In the early 8th century BC, a tribe on the middle Yangtze were called the Yángyuè, a term later used for peoples further south.[2] Between the 7th and 4th centuries BC "Yue" referred to the State of Yue in the lower Yangtze basin and its people.[2][6]

The term "Hundred Yue" first appears in the book Lüshi Chunqiu compiled around 239 BC.[7] It was used as a collective term for the non-Chinese populations of south and southwest China and northern Vietnam.[2]

Ancient texts mention a number of Yue states or groups. Most of these names survived into early imperial times:

| Chinese | Mandarin | Cantonese (Jyutping) | Zhuang | Vietnamese | Literal English trans.: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 於越/于越 | Yūyuè | jyu1 jyut6 | Ư Việt | Yue | |

| 揚越 | Yángyuè | joeng4 jyut6 | Dương Việt | Yang Yue | |

| 閩越 | Mǐnyuè | man5 jyut6 | Mân Việt | Min Yue | |

| 夜郎 | Yèláng | je6 long4 | Dạ Lang | Yelang | |

| 南越 | Nányuè | naam4 jyut6 | Namzyied | Nam Việt | Southern Yue |

| 山越 | Shānyuè | saan1 jyut6 | Sơn Việt | Mountain Yue | |

| 雒越 | Luòyuè | lok6 jyut6 | Lạc Việt | Sea Bird Yue | |

| 甌越 | Ōuyuè | au1 jyut6 | Âu Việt | Ou Yue |

Peoples of the lower Yangtze

In the 5th millennium BC, the lower Yangtze area was already a major population centre, occupied by the Hemudu (Austronesian) and Majiabang cultures, who were among the earliest cultivators of rice paddy fields in the fecund delta areas.[8]

By the 3rd millennium BC, the successor Liangzhu culture shows some influence from the Longshan-era cultures due to trade and commerce.[9] However, Y-chromosome DNA from Liangzhu culture sites shows a high frequency of haplogroup O-M119, which is also common among modern Taiwanese aborigines and speakers of Tai–Kadai languages in southwest China. Wucheng culture sites had a quite different profile, featuring haplogroups O-M95 and O-M122, which are found in several modern populations in east and southeast Asia, especially in Austroasiatic speakers.[10]

From the 9th century BC, two northern Yue tribes, the Gou-Wu and Yu-Yue, were increasingly influenced by their Chinese neighbours to their north. These two states were based in the areas of what is now southern Jiangsu and northern Zhejiang, respectively. Traditional accounts attribute the cultural change to Taibo, a Zhou prince who had self-exiled to the south. However, this piece of information originates from Shiji by Sima Qian, who tended to assign Chinese ancestors to most non-Chinese groups.[11] This practice, according to von Stella Xu, was used to justify the incorporation of non-Chinese people into his historical records.[11] Sima Qian also assigned Chinese ancestor to King Goujian of Yue, claiming that he was descended from the legendary Yu the Great. It is common to craft ancestor myths for non-Chinese people that justify Chinese expansions when needed and also explain the difference between Chinese-ness and non-Chinese-ness.[11]

The marshy lands of the south gave Gou-Wu and Yu-Yue unique characteristics. According to Robert Marks (2017:142), the Yue lived in what is now Fujian province gained their livelihood mostly from fishing, hunting, and practiced some kind of swidden rice farming.[12] Prior to Han Chinese migration from the north, the Yue tribes cultivated wet rice, practiced fishing and slash and burn agriculture, domesticated water buffalo, built stilt houses, tattooed their faces and dominated the coastal regions from shores all the way to the fertile valleys in the interior mountains.[13][14][15][16][17][18][19] Water transport was paramount in the south, so the two states became advanced in shipbuilding and developed maritime warfare technology mapping trade routes to Eastern coasts of China and Southeast Asia.[20][21] They were also known for their fine swords.

In the Spring and Autumn period, the two states, now called Wu and Yue, were becoming increasingly involved in Chinese politics.

In 512 BC, Wu launched a large expedition against the large state of Chu, based in the Middle Yangtze River. A similar campaign in 506 succeeded in sacking the Chu capital Ying. Also in that year, war broke out between Wu and Yue and continued with breaks for the next three decades. In 473 BC, Goujian finally conquered Wu and was acknowledged by the northern states of Qi and Jin. In 333 BC, Yue was in turn conquered by Chu.[22] After the fall of Yue, the ruling family moved south to what is now Fujian and established the Minyue kingdom.

What set the Yue apart from other Sinitic states of the time was their possession of a navy.[23] Yue culture was also distinct from the Chinese in its practice of naming boats and swords.[24] A Chinese text described the Yue as a people who used boats as their carriages and oars as their horses.[25]

The Yayoi people, the ancient people of Wa, in Japan are genetically and archeologically linked to the early people of the Yangtze-river and share several cultural aspects with them.[26]

Sinification and displacement

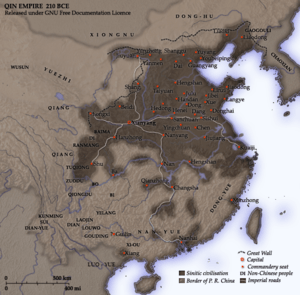

After the unification of China by Qin Shi Huang, the former Wu and Yue states were absorbed into the nascent Qin empire. The Qin armies also advanced south along the Xiang River to modern Guangdong and set up commanderies along the main communication routes. Motivated by the region's vast land and valuable exotic products, Emperor Qin Shi Huang is said to send a half of million troops divided into five armies to conquer the lands of the Yue.[27][28][29] The Yue defeated the first attack by Qin troops and killed the Qin commander.[28] A passage from Huai nan tzu of Liu An quoted by Keith Taylor (1991:18) describing the Qin defeat as follows:[30]

- The Yue fled into the depths of the mountains and forests, and it was not possible to fight them. The soldiers were kept in the garrisons to watch over abandoned territories. This went on for a long time, and the soldiers went weary. Then the Yue went out and attacked; the Chi'n (Qin) soldiers suffered a great defeat. Subsequently, convicts were sent to hold the garrisons against the Yue.

Afterwards, Qin Shi Huang sent reinforcements to defend against the Yue. By 214 BC, Guangdong, Guangxi and northern Vietnam were subjugated and reorganized into three prefectures within the Qin empire.[31] Qin Shi Huang imposed sinification by sending a large number of Chinese military agricultural colonists to what are now eastern Guangxi and western Guangdong.[32]

In 208 BC, the Qin Chinese renegade general Zhao Tuo defeated the kingdom of Ou Luo and captured its capital.[28] Towards the end of the Qin dynasty, many peasant rebellions led Zhao Tuo to claim independence from the imperial government and declared himself the emperor of Nanyue in 207 BC. Zhao led the peasants to rise up against the much despised Qinshi Emperor.[33] Zhao established his capital at Panyu (modern Guangzhou) and partitioned his empire into seven provinces.[28] Unlike Emperor Qin Shi Huang, Zhao respected Yue customs, rallied their local rulers, and forced local chiefs to be controlled by central government administrators, but let them continue their old policies and local political traditions.[33] Under Zhao's rule, he encouraged Han Chinese settlers to intermarry with the indigenous Yue tribes through instituting a policy of “Harmonizing and Gathering" while creating a syncretic culture that was a blend of Han and Yue (Tai) cultures.[31][28]

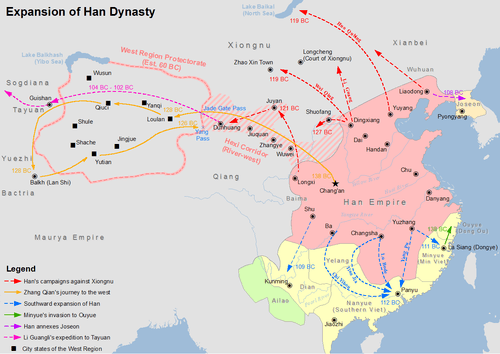

Following annexation of Nanyue, the Han dynasty set up two outposts which functioned as frontier garrisons.[34] The Han court also established nine commanderies in the former territory of Nanyue and the whole area was made part of the Han dynasty proper.[35] Nanyue was seen as attractive to the Han rulers as they desired to secure the area's maritime trade routes and gain access to luxury goods from the south such as pearls, incense, elephant tusks, rhinoceros horns, tortoise shells, coral, parrots, kingfishers, peacocks, and other rare luxuries to satisfy the demands of the Han aristocracy.[36][37][38] Other considerations such as frontier security, revenue from a relatively large agricultural population, and access to tropical commodities all contributed to the Han dynasty's determination to regain control of this region.[39]

Sinification of Nanyue was brought about by a combination of Han imperial military power, regular settlement and an influx of Han Chinese refugees, officers and garrisons, merchants, scholars, bureaucrats, fugitives, and prisoners of war.[40] Northern and central China was a theater of imperial dynastic conflict and huge episodes of dynastic conflict sent waves of Han Chinese refugees into the south. Throughout the Qin-Han period, large waves of Han Chinese immigrants from the northern and central plains slowly penetrated southern China.[41][42] The difficulty of logistics and the malarial climate in the south made Han migration and eventual sinification of the Yue a slow process.[43][44] Describing the contrast in immunity towards malaria between the indigenous Tai and the Chinese immigrants, Robert B. Marks (2017:145-146) writes:[45]

- The Tai population in southern China, especially those who lived in the lower reaches of the river valleys, may have had knowledge of the curative value of the "qinghao" plant, and possibly could also have acquired a certain level of immunity to malaria before Han Chinese even appeared on the scene. But for those without acquired immunity—such as Han Chinese migrants from north China—the disease would have been deadly.

After rebellions by Luo (Lac) peoples in 39-43 C.E., direct rule and greater efforts at sinification were imposed by the Han, the territories of the Luo (Lac) states were annexed and ruled directly, along with other former Yue territories to the north, as provinces of the Han empire.[46] Division among the Yue leaders were exploited by the Han dynasty with the Han military winning battles against the southern kingdoms and commandaries that were of geographic and strategic value to them. Han foreign policy also took advantage of the political turmoil among rival Yue leaders and enticed them with bribes and lured prospects for submitting to the Han Empire as a subordinate vassal.[47]

Motivation of Han dynasty to expand to the southern parts of the present-day China was driven, in part, from a desire to capture the region's exotic and rare goods, the abundance of untapped natural resources as well as securing international maritime trade routes.[48] Continuing internal migration of the Chinese during the Han dynasty eventually brought all the non-Chinese Yue coastal peoples scattered from Fujian to the Red River delta under Chinese political control and cultural influence.[49] As the number of Han Chinese migrants intensified following the annexation of Nanyue, the Yue people were gradually absorbed and driven out into poorer land on the hills and into the mountains.[50][51][52][53][54] Chinese military garrisons showed little patience with the Yue tribes who refused to submit to Han Chinese imperial power and resisted the influx of Han Chinese immigrants, driving them out to the coastal extremities and the highland areas where they became marginal scavengers and outcasts.[55] Han dynasty rulers saw the opportunity offered by the Chinese family agricultural settlements and used it as a tool for colonizing newly conquered regions and transforming those environments.[56]

Traditional Chinese view about the world has it that China was located at the center of the universe, superior to other nations and peoples, and that whose who lived in the peripheral territories were less culturally advanced for their perceived lack of civilization, and thus peripheral peoples were considered as "barbarians".[57] During the Han dynasty, it was advocated that Confucianism be used to re-educate and reform non-Han people as they were believed to be able to be culturally absorbed laihua, "come and be transformed", or hanhua, "become Han".[58] Some administrators of Han sought to "Confucianize" non-Han people of the south under their authority through the additional establishment of Confucianist institutes and schools dedicated towards teaching the texts, philosophies and morality of the north, but at the same time they attacked and put down the traditional spiritual leaders of the southern community who were described as "wu", magicians or shamans.[59]

Large numbers of Yue aborigines were eventually absorbed and assimilated into Chinese population while the remnants of the ancient Yue continue to live in the modern provinces of Zhejiang and Guangdong.[60][61][62][15][63][64][65] Speakers of the Tai-Kadai languages—in modern China such as the Zhuang, Nung, Tay, Bouyei, Dai, Sui, Kam, Hlai, Mulam, Anan, Ong Be, Thai, Lao, and Shan—retain their ethnic identities.[15][66]

Language

Knowledge of Yue speech is limited to fragmentary references and possible loanwords in other languages, principally Chinese. The longest is the Song of the Yue Boatman, a short song transcribed phonetically in Chinese characters in 528 BC and included, with a Chinese version, in the Garden of Stories compiled by Liu Xiang five centuries later.[67]

There is some disagreement about the languages they spoke, with candidates drawn from the non-Sinitic language families still represented in areas of southern China, Tai–Kadai, Hmong–Mien and Austroasiatic. The hypothesis proposed by Jerry Norman and Tsu-Lin Mei arguing for an Austroasiatic homeland along the middle Yangtze has been largely abandoned in most circles, and left unsupported by the majority of Austroasiatic specialists.[68] Chinese, Tai–Kadai, Hmong–Mien and the Vietic branch of Austroasiatic have similar tone systems, syllable structure, grammatical features and lack of inflection, but these features are believed to have spread by means of diffusion across the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, rather than indicating common descent.[69] Chamberlain (1998) posits that the Austroasiatic predecessor of modern Vietnamese language originated in modern-day Bolikhamsai Province and Khammouane Province in Laos as well as parts of Nghệ An Province and Quảng Bình Province in Vietnam, rather than in the region north of the Red River delta.[70]. However, Ferlus (2009) showed that the inventions of pestle, oar and a pan to cook sticky rice, which is the main characteristic of the Đông Sơn culture, correspond to the creation of new lexicons for these inventions in Northern Vietic (Việt–Mường) and Central Vietic (Cuoi-Toum).[71] The new vocabularies of these inventions were proven to be derivatives from original verbs rather than borrowed lexical items. The current distribution of Northern Vietic also correspond to the area of Đông Sơn culture. Thus, Ferlus concludes that the Northern Vietic (Viet-Muong) is the direct heirs of the Dongsonian, who have resided in Southern part of Red river delta and North Central Vietnam since the 1st millennium BC [71].

Wolfgang Behr (2002) points out that some scattered non-Sinitic words found in the two ancient Chinese fictional texts, Mu tianzi zhuan 穆天子傳 (4th c. B.C.) and Yuejue shu 越絕書 (1st c. A.D.), can be compared to lexical items in Tai-Kadai languages:

- "吳謂善「伊」, 謂稻道「缓」, 號從中國, 名從主人。"[72]

“The Wú say yī for ‘good’ and huăn for ‘way’, i.e. in their titles they follow the central kingdoms, but in their names they follow their own lords.”

伊 yī < MC ʔjij < OC *bq(l)ij ← Siamese diiA1, Longzhou dai1, Bo'ai nii1 Daiya li1, Sipsongpanna di1, Dehong li6 < proto-Tai *ʔdɛiA1 | Sui ʔdaai1, Kam laai1, Maonan ʔdaai1, Mak ʔdaai6 < proto-Kam-Sui/proto-Kam-Tai *ʔdaai1 'good'

缓 [huăn] < MC hwanX < OC *awan ← Siamese honA1, Bo'ai hɔn1, Dioi thon1 < proto-Tai *xronA1| Sui khwən1-i, Kam khwən1, Maonan khun1-i, Mulam khwən1-i < proto-Kam-Sui *khwən1 'road, way' | proto-Hlai *kuun1 || proto-Austronesian *Zalan (Thurgood 1994:353)

絕 jué < MC dzjwet < OC *bdzot ← Siamese codD1 'to record, mark' (Zhengzhang Shangfang 1999:8)

- "姑中山者越銅官之山也, 越人謂之銅, 「姑[沽]瀆」。"[73]

“The Middle mountains of Gū are the mountains of the Yuè’s bronze office, the Yuè people call them ‘Bronze gū[gū]dú.”

「姑[沽]瀆」 gūdú < MC ku=duwk < OC *aka=alok

← Siamese kʰauA1 'horn', Daiya xau5, Sipsongpanna xau1, Dehong xau1, Lü xău1, Dioi kaou1 'mountain, hill' < proto-Tai *kʰauA2; Siamese luukD2l 'classifier for mountains', Siamese kʰauA1-luukD2l 'mountain' || cf. OC 谷 gǔ < kuwk << *ak-lok/luwk < *akə-lok/yowk < *blok 'valley'

- "越人謂船爲「須盧」。"[74]

"... The Yuè people call a boat xūlú. (‘beard’ & ‘cottage’)"

? ← Siamese saʔ 'noun prefix'

← Siamese rɯaA2, Longzhou lɯɯ2, Bo'ai luu2, Daiya hə2, Dehong hə2 'boat' < proto-Tai *drɯ[a,o] | Sui lwa1/ʔda1, Kam lo1/lwa1, Be zoa < proto-Kam-Sui *s-lwa(n)A1 'boat'

- "[劉]賈築吳市西城, 名曰「定錯」城。"[75]

"[Líu] Jiă (the king of Jīng 荆) built the western wall, it was called dìngcuò ['settle(d)' & 'grindstone'] wall."

定 dìng < MC dengH < OC *adeng-s

← Siamese diaaŋA1, Daiya tʂhəŋ2, Sipsongpanna tseŋ2 'wall'

? ← Siamese tokD1s 'to set→sunset→west' (tawan-tok 'sun-set' = 'west'); Longzhou tuk7, Bo'ai tɔk7, Daiya tok7, Sipsongpanna tok7 < proto-Tai *tokD1s ǀ Sui tok7, Mak tok7, Maonan tɔk < proto-Kam-Sui *tɔkD1

Besides a limited number of lexical items left in Chinese historical texts, remnants of language(s) spoken by the ancient Yue can be found in non-Han substrata in Southern Chinese dialects, e.g. Wu, Min, Hakka, Yue, etc. Robert Bauer (1987) identifies twenty seven lexical items in Yue, Hakka and Min varieties, which share Tai-Kadai roots.[76] The following are some examples cited from Bauer (1987):[76]

- to beat, whip: Yue-Guangzhou faak7a ← Wuming Zhuang fa:k8, Siamese faatD2L, Longzhou faat, Po-ai faat.

- to beat, pound: Yue-Guangzhou tap8 ← Siamese thup4/top2, Longzhou tupD1, Po-ai tup3/tɔpD1, Mak/Dong tapD2, Tai Nuea top5, Sui-Lingam tjăpD2, Sui-Jungchiang tjăpD2, Sui-Pyo tjăpD2, T'en tjapD2, White Tai tup4, Red Tai tup3, Shan thup5, Lao Nong Khai thip3, Lue Moeng Yawng tup5, Leiping-Zhuang thop5/top4, Western Nung tup4, Yay tup5, Saek thap6, Tai Lo thup3, Tai Maw thup3, Tai No top5, Wuming Zhuang tup8, Li-Jiamao tap8.

- to bite: Yue-Guangzhou khap8 ← Siamese khop2, Longzhou khoop5, Po-ai hap3, Ahom khup, Shan khop4, Lü khop, White Tai khop2, Nung khôp, Hsi-lin hapD2S, Wuming-Zhuang hap8, T'ien-pao hap, Black Tai khop2, Red Tai khop3, Lao Nong Khai khop1, Western Nung khap6, etc.

- to burn: Yue-Guangzhou naat7a, Hakka nat8 ← Wuming Zhuang na:t8, Po-ai naatD1L "hot".

- child: Min-Chaozhou noŋ1 kiā3 "child", Min-Suixi nuŋ3 kia3, Mandarin-Chengdu nɑŋ1 pɑ1 kər1 "youngest sibling", Min-Fuzhou nauŋ6 "young, immature" ← Siamese nɔɔŋ4, Tai Lo lɔŋ3, Tai Maw nɔŋ3, Tai No nɔŋ3 "younger sibing", Wuming Zhuang tak8 nu:ŋ4, Longzhou no:ŋ4 ba:u5, Buyi nuaŋ4, Dai-Xishuangbanna nɔŋ4 tsa:i2, Dai-Dehong lɔŋ4 tsa:i2, etc.

- correct, precisely, just now: Yue-Guangzhou ŋaam1 "correct", ŋaam1 ŋaam1 "just now", Hakka-Meixian ŋam5 ŋam5 "precisely", Hakka-Youding ŋaŋ1 ŋaŋ1 "just right", Min-Suixi ŋam1 "fit", Min-Chaozhou ŋam1, Min-Hainan ŋam1 ŋam1 "good" ← Wuming Zhuang ŋa:m1 "proper" / ŋa:m3 "precisely, appropriate" / ŋa:m5 "exactly", Longzhou ŋa:m5 vəi6.

- to cover (1): Yue-Guangzhou hom6/ham6 ← Siamese hom2, Longzhou hum5, Po-ai hɔmB1, Lao hom, Ahom hum, Shan hom2, Lü hum, White Tai hum2, Black Tai hoom2, Red Tai hom3, Nung hôm, Tay hôm, Tho hoom, T'ien-pao ham, Dioi hom, Hsi-lin hɔm, T'ien-chow hɔm, Lao Nong Khai hom3, Western Nung ham2, etc.

- to cover (2): Yue-Guangzhou khap7, Yue-Yangjiang kap7a, Hakka-Meixian khɛp7, Min-Xiamen kaˀ7, Min-Quanzhou kaˀ7, Min-Zhangzhou kaˀ7 "to cover" ← Wuming-Zhuang kop8 "to cover", Li-Jiamao khɔp7, Li-Baocheng khɔp7, Li-Qiandui khop9, Li-Tongshi khop7 "to cover".

- to lash, whip, thrash: Yue-Guangzhou fit7 ← Wuming Zhuang fit8, Li-Baoding fi:t7.

- monkey: Yue-Guangzhou ma4 lau1 ← Wuming Zhuang ma4 lau2, Mulao mə6 lau2.

- to slip off, fall off, lose: Yue-Guangzhou lat7, Hakka lut7, Hakka-Yongding lut7, Min-Dongshandao lut7, Min-Suixi lak8, Min-Chaozhou luk7 ← Siamese lutD1S, Longzhou luut, Po-ai loot, Wiming-Zhuang lo:t7.

- to stamp foot, trample: Yue-Guangzhou tam6, Hakka tem5 ← Wuming Zhuang tam6, Po-ai tamB2, Lao tham, Lü tam, Nung tam.

- stupid: Yue-Guangzhou ŋɔŋ6, Hakka-Meixian ŋɔŋ5, Hakka-Yongfing ŋɔŋ5, Min-Dongshandao goŋ6, Min-Suixi ŋɔŋ1, Min-Fuzhou ŋouŋ6 ← Be-Lingao ŋən2, Wuming Zhuang ŋu:ŋ6, Li-Baoding ŋaŋ2, Li-Zhongsha ŋaŋ2, Li-Xifan ŋaŋ2, Li-Yuanmen ŋaŋ4, Li-Qiaodui ŋaŋ4, Li-Tongshi ŋaŋ4, Li-Baocheng ŋa:ŋ2, Li-Jiamao ŋa:ŋ2.

- to tear, pinch, peel, nip: Yue-Guangzhou mit7 "tear, break off, pinch, peel off with finger", Hakka met7 "pluck, pull out, peel" ← Be-Lingao mit5 "rip, tear", Longzhou bitD1S, Po-ai mit, Nung bêt, Tay bit "pick, pluck, nip off", Wuming Zhuang bit7 "tear off, twist, peel, pinch, squeeze, press", Li-Tongshi mi:t7, Li-Baoding mi:t7 "pinch, squeeze, press".

Robert Bauer (1996) points out twenty nine possible cognates between Cantonese spoken in Guangzhou and Tai-Kadai, of which seven cognates are confirmed to originate from Tai-Kadai sources:[77]

Cantonese kɐj1 hɔ:ŋ2 ← Wuming Zhuang kai5 ha:ŋ6 "young chicken which has not laid eggs"[78]

Cantonese ja:ŋ5 ← Siamese jâ:ŋ "to step on, tread"[79]

Cantonese kɐm6 ← Wuming Zhuang kam6, Siamese kʰòm, Be-Lingao xɔm4 "to press down"[80]

Cantonese kɐp7b na:3[lower-alpha 1] ← Wuming Zhuang kop7, Siamese kòp "frog"[81]

Cantonese khɐp8 ← Siamese kʰòp "to bite"[81]

Cantonese lɐm5 ← Siamese lóm, Maonan lam5 "to collapse, to topple, to fall down (building)"[82]

Cantonese tɐm5 ← Wuming Zhuang tam5, Siamese tàm "to hang down, be low"[83]

Li Hui (2001) identifies 126 Tai-Kadai cognates in Maqiao Wu dialect spoken in the suburbs of Shanghai out of more than a thousand lexical items surveyed.[84] According to the author, these cognates are likely traces of 'old Yue language' (gu Yueyu 古越語).[84]

Jerry Norman and Mei Tsu-Lin presented evidence that at least some Yue spoke an Austroasiatic language:[6][85][86]

- A well-known loanword into Sino-Tibetan[87] is k-la for tiger (Hanzi: 虎 old Chinese (ZS): *qʰlaːʔ > Mandarin pinyin: hǔ, Sino-Vietnamese "hổ") from Austroasiatic *klaʔ (compare Vietic kʰaːlʔ > *k-haːlʔ > kʰaːlʔ > Vietnamese khái).

- Zheng Xuan (127–200 AD) wrote that 扎 (middle Chinese: "jaat", modern Mandarin Chinese zā, modern Sino-Vietnamese: "trát") was the word used by the Yue people (越人) to mean "die". Norman and Mei reconstruct this word as OC *tsət and relate it to Austroasiatic words with the same meaning, such as Vietnamese chết and Mon chɒt. However, Laurent Sagart points out that 扎 is a well‑attested Chinese word also meaning 'to die', which is overlooked by Norman and Mei.[88] This word occurred in the Yue language in Han times could be because Yuè borrowed it from Chinese.[88] Therefore, the resemblance of this Chinese word to an Austroasiatic word is probably accidental.[88]

- According to the Shuowen Jiezi (100 AD), "In Nanyue, the word for dog is (Chinese: 撓獀; pinyin: náosōu; EMC: nuw-ʂuw)", possibly related to other Austroasiatic terms. Sōu is "hunt" in modern Chinese. However, in Shuowen Jiezi, the word for dog is recorded as 獶獀 with its most probable pronunciation around 100 CE must have been ou-sou or ou-ʂou, which resembles proto-Austronesian *asu, *u‑asu 'dog' than it resembles the palatal‑initialled Austroasiatic monosyllable Vietnamese chó, Old Mon clüw, etc.[89]

- The early Chinese name for the Yangtze (Chinese: 江; pinyin: jiāng; EMC: kœ:ŋ; OC: *kroŋ; Cantonese: "kong") was later extended to a general word for "river" in south China. Norman and Mei suggest that the word is cognate with Vietnamese sông (from *krong) and Mon kruŋ "river".

They also provide evidence of an Austroasiatic substrate in the vocabulary of Min Chinese.[6][90] Norman and Mei's hypothesis is widely quoted, but has recently been criticized by Laurent Sagart who suggest that on the most eastern coast Austronesian languages were spoken and in inland areas Austroasiatic languages.[91]

Scholars in China often assume that the Yue spoke an early form of Tai–Kadai. The linguist Wei Qingwen gave a rendering of the "Song of the Yue boatman" in Standard Zhuang. Zhengzhang Shangfang proposed an interpretation of the song in written Thai (dating from the late 13th century) as the closest available approximation to the original language, but his interpretation remains controversial.[67][89]

Legacy

The fall of the Han dynasty and the succeeding period of division sped up the process of sinicization. Periods of instability and war in northern and central China, such as the Northern and Southern dynasties and during the Song dynasty sent waves of Han Chinese into the south.[92] Waves of migration and subsequent intermarriage and cross-cultural dialogue has resulted to a mixture of Chinese and non-Chinese peoples in the south.[93][94] Large incoming waves of Han Chinese immigrants from Northern and Central China poured into the south over the centuries through various succeeding Chinese dynasties has resulted in large-scale intermixing between the Han Chinese and Yue with much of the indigenous Yue tribes assimilating into Chinese civilization or ended up being driven out into the hills and mountains.[95][96][50][97] Successive waves of migration in different localities during various times in Chinese history over the past two thousand years have given rise to different dialect groups seen in Southern China today.[98] Modern Lingnan culture contains both Nanyue and Han Chinese elements: the modern Cantonese language closely resembles Middle Chinese (the prestige language of the Tang Dynasty), but has retained some features of the long-extinct Nanyue language. Some distinctive features of the vocabulary, phonology, and syntax of southern varieties of Chinese are attributed to substrate languages that were spoken by the Yue.[99][100]

By the Tang dynasty (618–907), the term "Yue" had largely become a regional designation rather than a cultural one, as in the Wuyue state during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in what is now Zhejiang province.

In ancient China, the characters 越 and 粵 (both yuè in pinyin) were used interchangeably, but they are differentiated in modern Chinese:

- The character "越" refers to the original territory of the state of Yue, which was based in what is now northern Zhejiang, especially the areas around Shaoxing and Ningbo. The Shaoxing opera of Zhejiang, for example, is called "Yue Opera". It is also used to write Vietnam, a word adapted from Nányuè (Vietnamese: Nam Việt), (literal English translation as Southern Yue).

- The character "粵" is associated with the southern province of Guangdong. Both the regional dialects of Yue Chinese and the standard form, popularly called "Cantonese", are spoken in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, Macau and in many Cantonese communities around the world.

Notes

- ↑ The second syllable na:3 may correspond to Tai morpheme for 'field'.

References

- ↑ Luo, Yongxian (2008). "Sino-Tai and Tai-Kadai: another look". In Diller, Anthony; Edmondson, Jerry; Luo, Yongxian. The Tai-Kadai Languages. Routledge. pp. 9–28. ISBN 978-0700714575.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Meacham, William (1996). "Defining the Hundred Yue". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 15: 93. doi:10.7152/bippa.v15i0.11537.

- ↑ Barlow, Jeffrey G. (1997). "Culture, ethnic identity, and early weapons systems: the Sino-Vietnamese frontier". In Tötösy de Zepetnek, Steven; Jay, Jennifer W. East Asian cultural and historical perspectives: histories and society—culture and literatures. Research Institute for Comparative Literature and Cross-Cultural Studies, University of Alberta. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-921490-09-8.

- ↑ Brindley 2003, p. 13.

- ↑ Old Chinese pronunciation from Baxter, William H. and Laurent Sagart. 2014. Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction. Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5. These characters are both given as gjwat in Grammata Serica Recensa 303e and 305a.

- 1 2 3 4 Norman, Jerry; Mei, Tsu-lin (1976). "The Austroasiatics in Ancient South China: Some Lexical Evidence" (PDF). Monumenta Serica. 32: 274–301. JSTOR 40726203.

- ↑ The Annals of Lü Buwei, translated by John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel, Stanford University Press (2000), p. 510. ISBN 978-0-8047-3354-0. "For the most part, there are no rulers to the south of the Yang and Han Rivers, in the confederation of the Hundred Yue tribes."

- ↑ Marks (2017), p. 36.

- ↑ Chang, Kwang-chih; Goodenough, Ward H. (1996). "Archaeology of southeastern coastal China and its bearing on the Austronesian homeland". In Goodenough, Ward H. Prehistoric settlement of the Pacific. American Philosophical Society. pp. 36–54. ISBN 978-0-87169-865-0.

- ↑ Li, Hui; Huang, Ying; F Mustavich, Laura; Zhang, Fan; Tan, Jing-Ze; Wang, Ling-E; Qian, Ji; Gao, Meng-He; Jin, Li (November 2007). "Y chromosomes of prehistoric people along the Yangtze River". Human Genetics. 122 (3–4): 383–388. doi:10.1007/s00439-007-0407-2. PMID 17657509.

- 1 2 3 von Stella 2016, p. 36.

- ↑ Marks (2017), p. 142.

- ↑ Sharma, S. D. (2010). Rice: Origin, Antiquity and History. CRC Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1578086801.

- ↑ Brindley 2015, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 Him & Hsu (2004), p. 8.

- ↑ Peters, Heather (April 1990). H. Mair, Victor, ed. "TATTOOED FACES AND STILT HOUSES: WHO WERE THE ANClENT YUE?" (PDF). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. East Asian Collection. Sino-Platonic Papers. University of Pennsylvania Press. 17: 3.

- ↑ Cartier, Carolyn (2001). Globalizing South China. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1557868886.

- ↑ Marks (2017), p. 72.

- ↑ Marks (2017), p. 62.

- ↑ Lim, Ivy Maria (2010). Lineage Society on the Southeastern Coast of China. Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1604977271.

- ↑ Lu, Yongxiang (2016). A History of Chinese Science and Technology. Springer. p. 438. ISBN 978-3662513880.

- ↑ Brindley 2003, pp. 1–32.

- ↑ Holm 2014, p. 35.

- ↑ Kiernan 2017, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Kiernan 2017, p. 50.

- ↑ "Yayoi linked to Yangtze area". www.trussel.com.

- ↑ Hoang, Anh Tuan (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese relations, 1637-1700. Brill Academic Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-9004156012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Howard, Michael C. (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0786468034.

- ↑ Holcombe, Charles (2001). The Genesis of East Asia: 221 B.C. - A.D. 907. University of Hawaii Press (published May 1, 2001). p. 147. ISBN 978-0824824655.

- ↑ Taylor 1991, p. 18.

- 1 2 Him & Hsu (2004), p. 5.

- ↑ Huang, Pingwen. "Sinification of the Zhuang People, Culture, And Their Language" (PDF). SEALS. XII: 91.

- 1 2 Huang, Pingwen. "Sinification of the Zhuang People, Culture, And Their Language" (PDF). SEALS. XII: 92.

- ↑ Miksic, John Norman; Yian, Goh Geok (2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Routledge (published October 27, 2016). p. 157. ISBN 978-0415735544.

- ↑ Xu, Stella (2016). Reconstructing Ancient Korean History: The Formation of Korean-ness in the Shadow of History. Lexington Books (published May 12, 2016). p. 27. ISBN 978-1498521444.

- ↑ Kiernan, Ben (2017). A History of Vietnam, 211 BC to 2000 AD. Oxford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0195160765.

- ↑ Miksic, John Norman; Yian, Goh Geok (2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Routledge (published October 27, 2016). p. 158. ISBN 978-0415735544.

- ↑ Higham, Charles (1989). The Archaeology of Mainland Southeast Asia: From 10,000 B.C. to the Fall of Angkor. Cambridge University Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0521275255.

- ↑ Taylor 1991, p. 21.

- ↑ Taylor 1991, p. 24.

- ↑ Hsu, Cho-yun; Lagerwey, John (2012). Y. S. Cheng, Joseph, ed. China: A Religious State. Columbia University Press (published June 19, 2012). pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Weinstein, Jodi L. (2013). Empire and Identity in Guizhou: Local Resistance to Qing Expansion. University of Washington Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0295993270.

- ↑ Marks 2017, pp. 144-146.

- ↑ Hutcheon, Robert (1996). China-Yellow. The Chinese University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-9622017252.

- ↑ Marks 2017, pp. 145-146.

- ↑ McLeod, Mark; Nguyen, Thi Dieu (2001). Culture and Customs of Vietnam. Greenwood (published June 30, 2001). p. 15-16. ISBN 978-0313361135.

- ↑ Brindley 2015, pp. 249.

- ↑ . Kim, Nam C (2015). The Origins of Ancient Vietnam (Oxford Studies in the Archaeology of Ancient States). Oxford University Press (published November 2, 2015). p. 251. ISBN 978-0199980888.

- ↑ Stuart-Fox, Martin (2003). A Short History of China and Southeast Asia: Tribute, Trade and Influence. Allen & Unwin (published November 1, 2003). p. 18.

- 1 2 Marks, Robert B. (2011). China: An Environmental History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 127. ISBN 978-1442212756.

- ↑ Crooks, Peter; Parsons, Timothy H. (2016). Empires and Bureaucracy in World History: From Late Antiquity to the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press (published August 11, 2016). pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-1107166035.

- ↑ Ebrey, Patricia; Walthall, Anne (2013). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Wadsworth Publishing (published January 1, 2013). p. 53. ISBN 978-1133606475.

- ↑ Peterson, Glen (1998). The Power of Words: Literacy and Revolution in South China, 1949-95. University of British Columbia Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0774806121.

- ↑ Michaud, Jean; Swain, Margaret Byrne; Barkataki-Ruscheweyh, Meenaxi (2016). Historical Dictionary of the Peoples of the Southeast Asian Massif. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (published October 14, 2016). p. 163. ISBN 978-1442272781.

- ↑ Hutcheon, Robert (1996). China-Yellow. The Chinese University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-9622017252.

- ↑ Marks, Robert B. (2011). China: An Environmental History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 339. ISBN 978-1442212756.

- ↑ Novotny, Daniel (2010). Torn Between America and China: Elite Perceptions and Indonesian Foreign Policy. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (published August 23, 2010). p. 183. ISBN 978-9814279598.

- ↑ Tsung, Linda (2009). Minority Languages, Education and Communities in China. Palgrave Macmillan (published April 15, 2009). p. 37. ISBN 978-0230551480.

- ↑ de Crespigny, Rafe (June 7, 2004). "South China in the Han Period". Australian National University Press.

- ↑ Evans, Grant; Hutton, Christopher; Eng, Kuah Khun (2000). Where China Meets Southeast Asia: Social and Cultural Change in the Border Region (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1349631001.

- ↑ Crawford, Dorothy H.; Rickinson, Alan; Johannessen, Ingolfur (2014). Cancer Virus: The story of Epstein-Barr Virus. Oxford University Press (published March 14, 2014). p. 98.

- ↑ Wei, Da; Wang, David (2016). Urban Villages in the New China: Case of Shenzhen. Palgrave Macmillan (published October 29, 2016). p. 47. ISBN 978-1137504258.

- ↑ Benedict, Paul K.; Bauer, Robert (1997). Modern Cantonese Phonology. Mouton de Gruyter (published June 10, 1997). p. xxxix. ISBN 978-3110148930.

- ↑ 上海本地人源流主成分分析 Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 上海歷史上的民族變遷 Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Weinstein, Jodi L. (2013). Empire and Identity in Guizhou: Local Resistance to Qing Expansion. University of Washington Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0295993270.

- 1 2 Zhengzhang, Shangfang (1991). "Decipherment of Yue-Ren-Ge (Song of the Yue boatman)". Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale. 20 (2): 159–168. doi:10.3406/clao.1991.1345.

- ↑ Chamberlain, James R. (2016). "Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam", p. 30. In Journal of the Siam Society, Vol. 104, 2016.

- ↑ Enfield, N.J. (2005). "Areal Linguistics and Mainland Southeast Asia" (PDF). Annual Review of Anthropology. 34: 181–206. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120406.

- ↑ Chamberlain, J.R. 1998, "The origin of Sek: implications for Tai and Vietnamese history", in The International Conference on Tai Studies, ed. S. Burusphat, Bangkok, Thailand, pp. 97-128. Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University.

- 1 2 Ferlus, Michael (2009). "A Layer of Dongsonian Vocabulary in Vietnamese" (PDF). Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 1: 95–108.

- ↑ Behr 2002, pp. 1-2.

- 1 2 Behr 2002, p. 2.

- ↑ Behr 2002, pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Behr 2002, p. 3.

- 1 2 Bauer, Robert S. (1987). 'Kadai loanwords in southern Chinese dialects', Transactions of the International Conference of Orientalists in Japan 32: 95–111.

- ↑ Bauer (1996), pp. 1835-1836.

- ↑ Bauer (1996), pp. 1822-1823.

- ↑ Bauer (1996), p. 1823.

- ↑ Bauer (1996), p. 1826.

- 1 2 Bauer (1996), p. 1827.

- ↑ Bauer (1996), pp. 1828-1829.

- ↑ Bauer (1996), p. 1834.

- 1 2 Li 2001, p. 15.

- ↑ Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- ↑ Boltz, William G. (1999). "Language and Writing". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. The Cambridge history of ancient China: from the origins of civilization to 221 B.C. Cambridge University Press. pp. 74–123. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- ↑ Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus, http://stedt.berkeley.edu/~stedt-cgi/rootcanal.pl/etymon/5560

- 1 2 3 Sagart 2008, p. 142.

- 1 2 Sagart 2008, p. 143.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 18–19, 231

- ↑ Sagart 2008, pp. 141-143.

- ↑ Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- ↑ de Sousa (2015), p. 363.

- ↑ Wen, Bo; Li, Hui; Lu, Daru; Song, Xiufeng; Zhang, Feng; He, Yungang; Li, Feng; Gao, Yang; Mao, Xianyun; Zhang, Liang; Qian, Ji; Tan, Jingze; Jin, Jianzhong; Huang, Wei; Deka, Ranjan; Su, Bing; Chakraborty, Ranajit; Jin, Li (2004). "Genetic evidence supports demic diffusion of Han culture". Nature. 431: 302–305. doi:10.1038/nature02878. PMID 15372031.

- ↑ Wee, J. T., Ha, T. C., Loong, S. L., & Qian, C. N. (2010). Is nasopharyngeal cancer really a" Cantonese cancer"?. Chinese journal of cancer, 29(5), 517-526.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (2001). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History. Oxford University Press. p. 350. ISBN 978-0195135251.

- ↑ Marks (2017), pp. 146-149.

- ↑ Crawford, Dorothy H.; Rickinson, Alan; Johannessen, Ingolfur (2014). Cancer Virus: The story of Epstein-Barr Virus. Oxford University Press (published March 14, 2014). p. 98.

- ↑ de Sousa (2015), pp. 356–440.

- ↑ Yue-Hashimoto, Anne Oi-Kan (1972). Studies in Yue Dialects 1: Phonology of Cantonese. Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–32. ISBN 978-0-521-08442-0.

Sources

- Bauer, Robert S. (1996), "Identifying the Tai substratum in Cantonese" (PDF), Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Languages and Linguistics, Pan-Asiatic Linguistics V: 1 806- 1 844, Bangkok: Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University at Salaya.

- Behr, Wolfgang (2002). "Stray loanword gleanings from two Ancient Chinese fictional texts". 16e Journées de linguistique d'Asie Orientale, Centre de Recherches Linguistiques sur l’Asie Orientale (E.H.E.S.S.), Paris: 1–6.

- Brindley, Erica F. (2015), Ancient China and the Yue, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-08478-0.

- Brindley, Erica F. (2003), "Barbarians or Not? Ethnicity and Changing Conceptions of the Ancient Yue (Viet) Peoples, ca. 400–50 BC" (PDF), Asia Major. 16, no. 2: 1–32.

- de Sousa, Hilário (2015), "The Far Southern Sinitic languages as part of Mainland Southeast Asia" (PDF), in Enfield, N.J.; Comrie, Bernard., Languages of Mainland Southeast Asia: The State of the Art, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 356–440, ISBN 978-1-5015-0168-5.

- Him, Mark Lai; Hsu, Madeline (2004), Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities and Institutions, AltaMira Press, ISBN 978-0-759-10458-7.

- Holm, David (2014). "A Layer of Old Chinese Readings in the Traditional Zhuang Script". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities: 1–45.

- Kiernan, Ben (2017), Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-195-16076-5.

- Li, Hui (2001). "Daic Background Vocabulary in Shanghai Maqiao Dialect" (PDF). Proceedings for Conference of Minority Cultures in Hainan and Taiwan, Haikou: Research Society for Chinese National History: 15–26.

- Marks, Robert B. (2017), China: An Environmental History, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-1-442-27789-2.

- Sagart, Laurent (2008), "The expansion of Setaria farmers in East Asia", in Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia; Blench, Roger; Ross, Malcolm D.; Ilia, Peiros; Lin, Marie, Past human migrations in East Asia: matching archaeology, linguistics and genetics, Routledge, pp. 133–157, ISBN 978-0-415-39923-4,

Quote: in conclusion, there is no convincing evidence, linguistic or other, of an early Austroasiatic presence on the southeast China coast.

- Taylor, Keith W. (1991), The Birth of Vietnam, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0.

- von Stella, Xu (2016), Reconstructing Ancient Korean History: The Formation of Korean-ness in the Shadow of History, Lexington Books, ISBN 978-1-498-52145-1.

External links

- "The power of language over the past: Tai settlement and Tai linguistics in southern China and northern Vietnam", Jerold A. Edmondson, in Studies in Southeast Asian languages and linguistics, ed. by Jimmy G. Harris, Somsonge Burusphat and James E. Harris, 39–64. Bangkok, Thailand: Ek Phim Thai Co. Ltd.