Jura, Scotland

| Gaelic name |

|

|---|---|

| Norse name | Dýrøy |

| Meaning of name | Old Norse for 'deer island'[1] |

| Location | |

Jura Jura shown within Argyll and Bute | |

| OS grid reference | NR589803 |

| Coordinates | 56°00′N 5°54′W / 56°N 5.9°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Islay |

| Area | 366.92 km2 (142 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 8 [2] |

| Highest elevation | Beinn an Òir 785 m (2,575 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Argyll and Bute |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 196[3] |

| Population rank | 31 [2] |

| Population density | 0.5 people/km2[3][1] |

| Largest settlement | Craighouse |

| References | [1][4] |

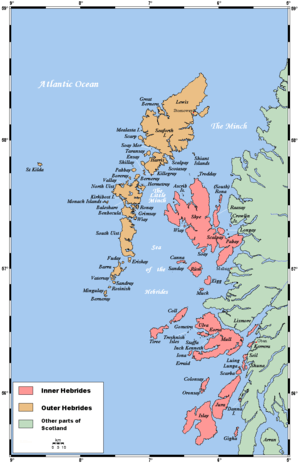

Jura (/ˈdʒʊərə/ JOOR-ə; Scottish Gaelic: Diùra [ˈtʲuːɾə]) is an island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland, adjacent to and to the north-east of Islay. With an area of 36,692 hectares, or 142 square miles, and only 196 inhabitants recorded in the 2011 census,[3] Jura is much more sparsely populated than neighbouring Islay, and is one of the least densely populated islands of Scotland: in a list of the islands of Scotland ranked by size, Jura comes eighth,[5] whereas ranked by population it comes 31st. Jura forms part of the council area of Argyll and Bute. The island is mountainous, bare and infertile, covered largely by vast areas of blanket bog, hence its small population.[6]

The main settlement is the village of Craighouse on the east coast. Craighouse is home to the Jura distillery, producing Isle of Jura single malt whisky.[7] The village is also home to the island's only hotel, shop and church.

Between the northern tip of Jura and the island of Scarba lies the Gulf of Corryvreckan, where a whirlpool makes passage dangerous at certain states of the tide. The southern part of the island, from Loch Tarbert southwards, is designated as a national scenic area (NSA),[8] one of 40 such areas in Scotland, which are defined so as to identify areas of exceptional scenery and to ensure its protection from inappropriate development by restricting certain forms of development.[9] The Jura NSA covers 30,317 hectares in total, consisting of 21,072 ha of land, with a further 9245 ha being marine (i.e. below low tide).[10]

Name

The modern name Jura dates from the Norse-Gael era. Two different Old Norse words have been suggested:

- Dyrøy meaning "deer island" is the generally accepted derivation.[1][11]

- Jurøy, meaning "udder island", in reference to the Paps of Jura.[1]

The name was recorded in 678 as Doraid Eilinn,[1] possibly meaning "Doraid's Island".[12]

Geology

The isle of Jura is composed largely of Dalradian quartzite, a hard metamorphic rock which provides the jagged surface of the Paps. Throughout the western half of the island the quartzite has been penetrated by a number of linear basalt dikes which were formed during a period of intense volcanic activity in the Lower Tertiary period, some 56 million years ago. These dikes are most apparent on the west coast, where erosion of the less-resistant rock into which they are intruded has left them exposed as natural walls. The west coast also has a number of raised beaches, which are regarded as a geological feature of international importance.[13]

Paps of Jura

The island is dominated by three steep-sided conical quartzite mountains on its western side – the Paps of Jura – which rise to 785 metres (2,575 ft).[14] There are three major peaks:

- Beinn an Òir (Gaelic: mountain of gold) is the highest peak, standing at 785 metres (2,575 ft),[14] and is thereby a Corbett.

- Beinn Shiantaidh (Gaelic: holy mountain) stands at 757 metres (2,484 ft) high.[14]

- Beinn a' Chaolais (Gaelic: mountain of the kyle) is the lowest of the Paps, reaching 733 metres (2,405 ft).[15][14]

The Paps dominate the landscape in the region and can be seen from the Mull of Kintyre and, on a clear day, from the Skye and Northern Ireland. The route of the annual Isle of Jura Fell Race includes all three Paps and four other hills.

These hills were the subject of William McTaggart's 1902 painting The Paps of Jura,[16] now displayed in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.[17]

History

Early years

Evidence of settlements on Jura dating from the Mesolithic period was first uncovered by the English archaeologist John Mercer in the 1960s.[18] There is a Neolithic chambered cairn at Poll a' Cheo in the southwest of the island.[19]

Jura is closer to Ulster than Glasgow, so it is should not be unexpected that the Irish crossed the straits of Moyle and established the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata. It was divided into a handful of regions, controlled by particular kin groups, of which the Cenél nÓengusa controlled Jura and Islay.

The kingdom thrived for a few centuries, and formed a springboard for Christianisation of the mainland. It is believed that Jura may have been Hinba, the island to which the 6th century missionary, Columba, retreated from the monastic community he founded on Iona, when he wished for a more contemplative life.[20]

Vikings

Dál Riata was ultimately destroyed when Vikings invaded, and established their own domain, spreading more extensively over the islands north and west of the mainland, including Jura. This became the Kingdom of the Isles, but following the unification of Norway, the islands were under tenuous Norwegian authority, somewhat resisted by local rulers, like Godred Crovan. Following Godred's death, the local population resisted Norway's choice of replacement, causing Magnus, the Norwegian king, to launch a military campaign to assert his authority. In 1098, under pressure from Magnus, the king of Scotland quitclaimed to him all sovereign authority over the isles.

To Norway, the islands became known as Suðreyjar (Old Norse, traditionally anglicised as Sodor), meaning southern isles. The former territory of Dal Riata acquired the geographic description Argyle (now Argyll): the Gaelic coast.

Half a century later, however, Somerled, the husband of Godred Crovan's granddaughter, led a successful revolt against Norway, transforming Suðreyjar into an independent kingdom. Somerled built the sea fortress of Claig Castle on an island at the southern tip of Jura, establishing control of the Sound of Islay; on account of the Corryvreckan whirlpool, this essentially gave him control of the sea traffic between the Scottish mainland and the Hebrides.

After his death, nominal Norwegian authority was re-established, but de-facto authority was split between Somerled's sons and the Crovan dynasty. Somerled's son Dougall received the part of Jura north of Loch Tarbert (along with adjacent islands further north), while Dougal's nephew Donald received the rest of Jura, as well as Islay, and lands to the east. It is unclear why Jura was split like this, but it may have been connected to a dispute with Donald's other uncle, Angus, who Donald and his brother had ultimately dispossessed.

In the mid 13th century, increased tension between Norway and Scotland led to a series of Battles, culminating in the Battle of Largs, shortly after which the Norwegian king died. In 1266, his more peaceable successor ceded his nominal authority over Suðreyjar to the Scottish king (Alexander III) by the Treaty of Perth, in return for a very large sum of money. Alexander generally acknowledged the semi-independent authority of Somerled's heirs.

Lords of the Isles

At the end of the 13th century, king John Balliol was challenged for the throne by Robert de Bruys. By this point, Somerled's descendants had formed into three families - the heirs of Dougall (the MacDougalls), those of Donald (the MacDonalds), and those of Donald's brother (the MacRory); the MacDougalls took John's side, while the MacDonalds and MacRory backed de Bruys. When de Bruys defeated John, he declared the MacDougall lands forfeit, and gave them to the MacDonalds. John of Islay, the head of the MacDonald family married the heir of the MacRory family, thereby acquiring the remaining share of Somerled's realm, and transforming it into the Lordship of the Isles, which lasted for over a century.

Throughout all this time, the descendants of the Cenél nÓengusa had retained their identity; they were now the MacInnes (not to be confused with similarly named groups elsewhere in Scotland). Though the MacDougalls had had authority over part of Jura, the MacInnes had been left in unmolested possession of the land, as vassals. Now, however, with the MacDonalds in charge of the entire island, the situation changed. The head of the MacDonalds was unhappy to have tenants who had supported John Balliol and the MacDougalls, so, in 1358, he asked the chief of the MacLean family to assassinate the MacInnes' leaders; so thorough was this carried out that to this day the MacInnes have had no-one to become their new chief, and consequently they dispersed throughout Scotland.

In 1390, the head of the MacDonald family - the Lord of the Isles - granted the MacLeans the lands of northern Jura (the lands which had belonged to the MacInnes). The MacLeans established a castle in Glen Garrisdale, as a stronghold, which they named Aros Castle, like one of their castles elsewhere.

Towards the end of the 15th century, the Lords of the Isles made increasing efforts to establish full independence; at the end of the century John MacDonald, the then Lord, launched a severe raid on Ross, in pursuance of this aim. Within 2 years of the raid, in 1493, the Lordship of the Isles was declared forfeit, and his realm became part of Scotland, rather than a dependency of the Scottish crown. John was exiled from his former lands, and his former subjects now considered themselves to have no superior except the king. A charter was soon sent from the Scottish King confirming this state of affairs; the charter declares that Skye and the Outer Hebrides are to be considered independent from the rest of the former Lordship, leaving only Islay and Jura remaining.

Campbells

Initially, the MacDonalds of Dunnyveg remained landlords of the southern part of Jura. However, following John MacDonald's death, his heir was Black Donald, his grandson, who had been kept a prisoner at Innes Chonnel Castle (a stronghold of the Campbells). In 1501, Donald escaped, triggering an insurrection in his favour in parts of the former Lordship of the Isles. When Donald was recaptured, in 1506, the king took the precaution of transferring the property of the MacDonald family to the Campbells; in Jura, the Campbells of Craignish were the beneficiaries.[21]

The Campbells established a base for themselves at Ardfin, at the south of Jura, to replace the nearby MacDonald stronghold of Claig Castle. After a century of intermittent violence between the families, in 1607 the Campbells purchased from the MacDonalds a quitclaim of any rights the latter might have on Jura.

Following the Scottish reformation, the MacLeans (opponents) and Campbells (supporters) came into dispute; to a certain extent, the Campbells also saw it as an opportunity for territorial expansion. Having complained for several years about harassment from the MacLeans, in 1647 the Campbells launched a surprise attach on Aros Castle, and killed many MacLeans; for many years in the 20th century, a human skull stood on a ledge in a nearby cave, and it was traditionally said to have been the remains of a Maclean who had been killed in this battle.[22] The skull is no longer there, but the latest editions of Ordnance Survey maps still mark the location as 'Maclean's Skull Cave'.[14]

The north of the island, however, remained in MacLean hands until 1737, when it was sold to Donald MacNeil of Colonsay. The remainder of the island was ruled and largely owned by the Campbells for a total of three centuries, by eleven successive Campbell lairds. Under Campbell influence, shrieval authority was established under the sheriff of Argyll. With inherited Campbell control of the sheriffdom, comital authority was superfluous, and the provincial identity (medieval Latin:provincia) of Islay-Jura faded away. In the mid 18th century, The Heritable Jurisdictions Act abolished both, leaving only the shrieval unit, and without Campbell control.

Emigration

Beginning in the later 18th century, long before the notorious Highland Clearances of the following century, there were several waves of emigration from Jura. In 1767, fifty people left for Canada, and from that point the population fluctuated, rising to a peak of 1312 in 1831, before gradually shrinking to its 20th century level of just a few hundred. Mercer notes[23] that although relatively few forced clearances on Jura were recorded, the emigrations were far from voluntary, being the result of factors such as hunger and spiralling rents. In 1881, the old Campbell mansion at Ardfin was demolished, and replaced by Jura House, a mere family home.

Recent history

Census records show that Jura's population peaked at 1,312 in 1831,[1] and that, in common with many areas of western Scotland, the island's population declined steadily over the ensuing decades. However, there has been a small increase since 2001.[24] During the decade from 2001 to 2011 Scottish island populations as a whole grew by 4% to 103,702.[25] Alongside the long-term decline in Jura's population has been a decline in the number of Gaelic speakers. The 1881 census reported that 86.6% (out of 946 inhabitants) spoke Gaelic. In 1961, for the first time less than half (46.9%) spoke the language and by 2001, this figure had dropped to 10.6%.

During the first half of the 20th century, the Campbells gradually sold the island as a number of separate estates, and the Campbell connection with Jura ended in 1938 with the sale of Jura House and its surrounding Ardfin Estate.[1]

In his later life, George Orwell moved to Barnhill, on Jura, living there intermittently from 1946, while critically ill with tuberculosis, until his death in January 1950. He was known to the residents of Jura by his real name, Eric Blair. It was at Barnhill that Orwell finished Nineteen Eighty-Four, during 1947–48;[26] he sent the final typescript to his publishers, Secker and Warburg, on 4 December 1948, and they published the book on 8 June 1949.[27] Despite its isolation, Barnhill has in recent years become something of a shrine for his readers.[28]

Government and politics

In 1899, counties were formally created, on shrieval boundaries, by a Scottish Local Government Act, under which Jura became part of the County of Argyll. In 1975 the counties were replaced by a two-tier system of regions and districts: Jura formed part of the Argyll and Bute district within the wider Strathclyde region, however the County of Argyll continues in use as a registration county. A further re-organisation took place in 1995, and Jura now forms part of the unitary council area of Argyll and Bute. The island also has a community council,[29] which is responsible primarily for representing the views of the local community in dealings with other public bodies, although it can also undertake other activities such as fundraising for local projects and the running of community events.[30]

In the Scottish Parliament Jura forms part of the constituency of Argyll and Bute, which elects one Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) by the first past the post method of election. It is also one of eight constituencies in the Highlands and Islands electoral region, which elects seven additional members, in addition to the eight constituency MSPs, to produce a form of proportional representation for the region as a whole. The current MSP for Argyll and Bute is Michael Russell of the Scottish National Party (SNP). At Westminster Jura is represented as part of a constituency also called Argyll and Bute, which is held by Brendan O'Hara, also of the SNP.

Modern ownership

There are now seven estates on Jura, all in separate ownership, with six of the seven held by absentees[31]:

- Ardfin: situated at the southern tip of the island, between Feolin and Craighouse. For some seventy years from 1938, Ardfin belonged to the Riley-Smith family, brewers from Tadcaster in Yorkshire. In 2010 the estate was bought by Greg Coffey, an Australian hedge fund manager,[32] and since then the famous walled garden of Jura House, which had previously been a popular tourist attraction, has been closed to the public. Having also wound up the estate's farm, Coffey then submitted proposals for the construction of a private 18-hole golf course on the estate, which was completed in 2017.

- Inver: lying North of Ardfin, on the west flanks of the Paps of Jura, and belonging to Sir William Lithgow,[33] Vice-Chairman of the Glasgow shipbuilding group Lithgows.

- Jura Forest: also lying north of Ardfin, but on the east flanks of the Paps of Jura. Forest Estate belongs to the Vestey family,[34] currently headed by Samuel, 3rd Baron Vestey, chairman of the food and farming business Vestey Group Ltd, and Master of the Horse of the Royal Household.

- Tarbert: North of the Corran River, and stretching as far as Loch Tarbert. Former Prime Minister David Cameron has visited the estate on several occasions.[35] It is sometimes reported that the 20,000-acre estate is "owned by his wife's stepfather Lord Astor"[35] although the ownership of the Tarbert Estate is in the hands of Ginge Manor Estates Ltd, based in Nassau in the Bahamas, and there is "no means of verifying" who the beneficial owners are.[36]

- Ruantallain: immediately north of Loch Tarbert. Ruantallain had been a part of the Tarbert Estate, until its sale in 1984. It is owned by businessman Lindsay Bury,[37] who is a former president of the influential wildlife charity Flora and Fauna International.

- Ardlussa: north of Ruantallain. The owner of Ardlussa[38] is Andrew Fletcher, who lives at Ardlussa House with his family - they are the only estate owners to be permanently resident on Jura.

- Barnhill: at the northernmost tip of Jura, overlooking the famous Corryvreckan Whirlpool,[39] Barnhill is also owned by a member of the Fletcher family, in this case Jamie Fletcher.

There is also a relatively small area owned by Forestry Commission Scotland.

Economy

In an economic survey published in 2005 by the now-defunct Feolin Study Centre on Jura,[40] the gross turnover of the island was estimated to be just over £3.2 million. This figure covered production and services only, and took no account of public expenditure by government or local authority. In financial terms, the Jura distillery was the largest, and it was also the biggest individual employer, but the island's seven estates, taken together, employed the most full- and part-time staff. The distillery is owned by Whyte and Mackay, which in 2014 was taken over by Emperador Distillers, part of the Alliance Global Group Inc of the Philippines. The estates provide deer stalking and other field sports, together with forestry and a diminishing amount of agriculture. In 2015 a new distillery was established in the north of the island, producing Lussa Gin.[41] Tourism is the only other significant area of economic activity, and in 2005 over 20% of the island population was directly or indirectly employed in the tourist industry. The distillery, field sports and Jura House Gardens were listed as the main tourist attractions, although the gardens have since been closed to the public.

In 2013 Jura Development Trust secured financial support from the Big Lottery Fund and other sources to purchase the island's only shop, which re-opened as a community-owned business in 2014.[42] The trust is also exploring renewable energy options.

Transport

Jura lies close to the Scottish mainland, and yet it is often described as "remote";[43] the island's most distinguished resident, George Orwell, famously described it as "extremely ungetatable".[44] This may be because it has no direct air or ferry link to the mainland, apart from a passenger ferry which runs, in the summer only, from the village of Tayvallich near Lochgilphead.[45] Most travellers to Jura go by CalMac car ferry from Kennacraig on the Kintyre Peninsula to Islay, and then cross to Jura from Port Askaig on Islay by the MV Eilean Dhiura, a small vehicle ferry which is run by ASP Ships on behalf of Argyll and Bute Council. Islay can also be reached by air: Islay Airport is served by daily flights from Glasgow operated by Loganair,[46] and twice weekly flights from Oban and Colonsay operated by Hebridean Air Services.[47]

Jura has only one road of any significance, the single-track A846, which follows the southern and eastern coastline of the island from Feolin Ferry to Craighouse, a distance of around eight miles (13 km). The road then continues to Lagg, Tarbert, Ardlussa and beyond. A private track runs from the road end to the far north of the island.[14] A local bus service on the island is operated by Garelochhead Coaches.[48]

Wildlife and conservation

| Jura National Scenic Area | |

|---|---|

A map of the Jura National Scenic Area | |

| Location | Argyll and Bute, Scotland |

| Area | 303 km2 (117 sq mi)[10] |

| Established | 1981 |

| Governing body | Scottish Natural Heritage |

The island has a large population of red deer.[49] Through browsing, the deer prevent the vegetation on the island from turning back to woodland, which is the natural climax community; indeed an alternative explanation of the island's name is that it derives from 'the great quantity of yew trees which grew in the island'[50] in earlier times.

Jura is also noted for its bird life, and especially for its raptors, including buzzards, golden eagles, white-tailed eagles and hen harriers.[49] Since 2010 Jura has been designated by Scottish Natural Heritage as a Special Protection Area for golden eagles.[51] Like many other parts of the Hebrides and western Scotland, the shores of Jura are frequented by grey seals, and the elusive otter is also relatively common here, as is the adder, the UK's only venomous snake.[49] The seas around Jura form part of the Inner Hebrides and the Minches Special Area of Conservation due to their importance for Harbour porpoises.[52]

Literary accounts

In 1549, Donald Monro, Dean of the Isles, wrote that the island was "ane ather fyne forrest for deire, inhabit and manurit at the coist syde", with "fresche water Loches, with meikell of profit" and an abundance of salmon.[53][Note 1]

However, when the soldier and military historian Sir James Turner visited Jura in 1632, he was less impressed, reporting that '[it is] a horride ile and a habitation fit for deere and wild beastes'.[54]

But at the end of the 17th century, the writer and traveller Martin Martin went there and concluded that 'this isle is perhaps the wholesomest plot of ground either in the isles or continent of Scotland, as appears by the long life of the natives and their state of health'. Martin noted some extraordinary examples of longevity, including one Gillouir MacCrain, who was alleged to have kept one hundred and eighty Christmases in his own house. And he was impressed by the good health of the inhabitants: 'There is no epidemical disease that prevails here. Fevers are but seldom observed by the natives, and any kind of flux is rare. The gout and agues are not so much as known by them, neither are they liable to sciatica. Convulsions, vapours, palsies, surfeits, lethargies, megrims, consumptions, rickets, pains of the stomach or coughs, are not frequent here, and none of them are at any time observed to become mad.'[55]

Culture

Like all inhabited Hebridean islands, Jura has its own indigenous tradition of Gaelic song and poetry.[56][57] Since 1993 it has also been the home of the Jura Music Festival,[58] which takes place annually in September.

Jura is also known for an event of 23 August 1994, when Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty, known then as the music group the KLF, filmed themselves burning £1 million in banknotes in the Ardfin boathouse on the south coast of the island.[59]

Jura is featured in the plot of the 2003 novel A Question of Blood by Ian Rankin, and the 2007 novel The Careful Use of Compliments by the Scottish writer Alexander McCall Smith, and is a setting for some of the narrative and action in Anne Michaels' 2008 novel The Winter Vault.

In music, Jura is mentioned in: "Crossing to Jura", a song by R. Kennedy and D. MacDonald, recorded in 1997 by JCB with Jerry Holland on the album A Trip to Cape Breton; "The Bens of Jura", a song by Capercaillie; and "Isle of Jura", a song by Skyclad.

The 2010 album Poets and Lighthouses by Tuvan singer Albert Kuvezin of the band Yat Kha was recorded and produced by the British musician Giles Perring on Jura, with some of the performances being recorded in the forest at Lagg. The album reached Number 1 in the European World Music Charts in January 2011.[60]

Notes

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 47

- 1 2 Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- 1 2 3 National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013) (pdf) Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland - Release 1C (Part Two). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland’s inhabited islands". Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ↑ Anderson, Joseph (Ed.) (1893) Orkneyinga Saga. Translated by Jón A. Hjaltalin & Gilbert Goudie. Edinburgh. James Thin and Mercat Press (1990 reprint). ISBN 0-901824-25-9

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 502

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 49-50

- ↑ isleofjura.com Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ↑ "Map: Jura National Scenic Area" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. December 2010. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- ↑ "National Scenic Areas". Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 2018-01-17.

- 1 2 "National Scenic Areas - Maps". SNH. 2010-12-20. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ↑ Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Jura". Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ↑ "West coast of Jura". scottishgeology.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ordnance Survey Landranger 1:50000, Sheet 61 (Jura and Colonsay).

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 50

- ↑ "William McTaggart". Machrihanish Online. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ↑ "Kelvingrove Art Gallery". planetware.com. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ↑ Mercer, John (1974). Hebridean Islands. Glasgow: Blackie. ISBN 0-216-89726-2.

- ↑ "Jura, Cladh Chlainn Iain". Historic Environment Scotland. 2018. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "The Road North". undiscoveredscotland.co.uk.

- ↑ "Isle of Jura - Island of Deer". Southern Hebrides of Scotland.

- ↑ "Jura, Maclean's Skull". scotlandsplaces.gov.uk.

- ↑ Mercer, J: Hebridean Islands (1974) ISBN 0 216 89726 2

- ↑ General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ↑ "Scotland's 2011 census: Island living on the rise". BBC News. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ Bowker, Gordon (2004). George Orwell. London: Abacus. ISBN 0-316-86115-4.

- ↑ Bowker (2004) p. 383, 399.

- ↑ Paul McHugh (March 15, 2009). "Finding Orwell's Source of Hope in Jura, Scotland". Washington Post.

- ↑ "Community Councillors". Argyll and Bute Council. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ↑ "Community Councils". Argyll and Bute Council. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ↑ "Who Owns Scotland". whoownsscotland.org.uk.

- ↑ "Nocookies". The Australian.

- ↑ "Property Page: Inver Estate". Who Owns Scotland. 2002-12-30. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "Property Page: Forest Estate". Who Owns Scotland. 2002-09-30. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- 1 2 "David Cameron suffers 'phenomenally bad back'. " BBC News. (19 August 2013) Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Ross, David (22 August 2013) "Cameron urged to clarify estate ownership".

- ↑ "Property Page: Ruantallen Estate". Who Owns Scotland. 2002-10-21. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "Ardlussa Estate Isle of Jura - Isle of Jura Accommodation - Ardlussa House". ardlussaestate.com.

- ↑ "Escape to jura". escapetojura.com.

- ↑ 'The Jura Economic Survey' (Feolin Study Centre, 2005)

- ↑ Page, Front. "LUSSA GIN - From the wilderness of the Isle of Jura".

- ↑ "juracommunityshop".

- ↑ Tim Jonze. "Jura: a brief guide to David Cameron's remote holiday retreat". the Guardian.

- ↑ Maev Kennedy. "Maev Kennedy: People". the Guardian.

- ↑ "home - Jura Passenger Ferry". jurapassengerferry.com.

- ↑ "Destinations: Islay". Glasgow Airport. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- ↑ "Timetables". Hebridean Air Services. 2017. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- ↑ "Home - Garelochhead Coaches". garelochheadcoaches.co.uk.

- 1 2 3 "Isle of Jura Wildlife". Jura Info. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ Statistical account of Scotland - Account of 1791-99 vol.12 p. 318

- ↑ "Site Details for Jura, Scarba and the Garvellachs". Scottish Natural Heritage. 2018-03-05. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ "Site Details for Inner Hebrides and the Minches". Scottish Natural Heritage. 2018-03-05. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- ↑ Monro (1549) "Duray" No. 15

- ↑ "The island‐parish of Jura - Scottish Geographical Magazine - Volume 84, Issue 1". Scottish Geographical Magazine. 84: 56–65. doi:10.1080/00369226808736072.

- ↑ Martin, Martin. "A description of the Western Islands of Scotland (1697)". appins.org. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007.

- ↑ Simon Ager. "Toirt m' aghaidh ri Diùra". Omniglot. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ↑ "Da Thaobh Loch Seile". all celtic music. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ↑ "Jura Music Festival". Jura Music Festival.

- ↑ Reid, J., "Money to burn Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine." (25 September 1994) London. The Observer.

- ↑ "Mongolian throat singer Kuvezin is the latest pride of Jura". Herald Scotland.

References

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Monro, Sir Donald (1549) Description of the Western Isles of Scotland. William Auld. Edinburgh - 1774 edition.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jura. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Jura. |

- Digitised historic map TIura Insula, The Yle of Iura one of the westerne Iles of Scotland from the Blaeu Atlas of Scotland by Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu published in 1654

- Isle of Jura Isle of Jura Information, Images and Jura Blog

- Jura on Scotlandview Isle of Jura Pictures and Comprehensive info

- Orwell's life on Jura