Iron(II) sulfide

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Iron sulfide, ferrous sulfide, black iron sulfide, protosulphuret of iron | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.881 |

PubChem CID |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| FeS | |

| Molar mass | 87.910 g/mol |

| Appearance | Gray, sometimes in lumps or powder |

| Density | 4.84 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 1,194 °C (2,181 °F; 1,467 K) |

| negligible (insoluble) | |

| Solubility | reacts in acid |

| +1074·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Source of hydrogen sulfide, can be pyrophoric |

| NFPA 704 | |

| variable | |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds |

Iron(II) oxide Iron disulfide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Iron(II) sulfide or ferrous sulfide (Br.E. sulphide) is one of a family chemical compounds and minerals with the approximate formula FeS. Iron sulfides are often iron-deficient non-stoichiometric. All are black, water-insoluble solids.

Preparation and structure

FeS can be obtained by the heating of iron and sulfur:[1]

- Fe + S → FeS

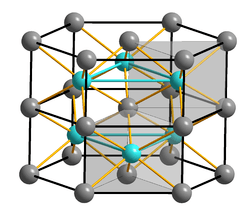

FeS adopts the nickel arsenide structure, featuring octahedral Fe centers and trigonal prismatic sulfide sites.

Reactions

Iron sulfide reacts with hydrochloric acid, releasing hydrogen sulfide

- FeS + 2 HCl → FeCl2 + H2S

- FeS + H2SO4 → FeO + H2O + SO2

In moist air, iron sulfides oxidize to hydrated ferrous sulfate.

Biology and biogeochemistry

Iron sulfides occur widely in nature in the form of iron–sulfur proteins.

As organic matter decays under low-oxygen (or hypoxic) conditions such as in swamps or dead zones of lakes and oceans, sulfate-reducing bacteria reduce various sulfates present in the water, producing hydrogen sulfide. Some of the hydrogen sulfide will react with metal ions in the water or solid to produce iron or metal sulfides, which are not water-soluble. These metal sulfides, such as iron(II) sulfide, are often black or brown, leading to the color of sludge.

Pyrrhotite is a waste product of the Desulfovibrio bacteria, a sulfate reducing bacteria.

When eggs are cooked for a long time, the yolk's surface may turn green. This color change is due to iron(II) sulfide, which forms as iron from the yolk reacts with hydrogen sulfide released from the egg white by the heat.[2] This reaction occurs more rapidly in older eggs as the whites are more alkaline.[3]

The presence of ferrous sulfide as a visible black precipitate in the growth medium peptone iron agar can be used to distinguish between microorganisms that produce the cysteine metabolizing enzyme cysteine desulfhydrase and those that do not. Peptone iron agar contains the amino acid cysteine and a chemical indicator, ferric citrate. The degradation of cysteine releases hydrogen sulfide gas that reacts with the ferric citrate to produce ferrous sulfide.

See also

References

- ↑ H. Lux "Iron (II) Sulfide" in Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. Edited by G. Brauer, Academic Press, 1963, NY. Vol. 1. p. 1502.

- ↑ Belle Lowe (1937), "The formation of ferrous sulfide in cooked eggs", Experimental cookery from the chemical and physical standpoint, John Wiley & Sons

- ↑ Harold McGee (2004), McGee on Food and Cooking, Hodder and Stoughton