Pyrite

| Pyrite | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Sulfide mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | FeS2 |

| Strunz classification | 2.EB.05a |

| Dana classification | 2.12.1.1 |

| Crystal system | Isometric |

| Crystal class |

Diploidal (m3) H-M symbol: (2/m 3) |

| Space group | Pa3 |

| Unit cell | a = 5.417 Å, Z = 4 |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 119.98 g/mol |

| Color | Pale brass-yellow reflective; tarnishes darker and iridescent |

| Crystal habit | Cubic, faces may be striated, but also frequently octahedral and pyritohedron. Often inter-grown, massive, radiated, granular, globular, and stalactitic. |

| Twinning | Penetration and contact twinning |

| Cleavage | Indistinct on {001}; partings on {011} and {111} |

| Fracture | Very uneven, sometimes conchoidal |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 6–6.5 |

| Luster | Metallic, glistening |

| Streak | Greenish-black to brownish-black |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque |

| Specific gravity | 4.95–5.10 |

| Density | 4.8–5 g/cm3 |

| Fusibility | 2.5–3 to a magnetic globule |

| Solubility | Insoluble in water |

| Other characteristics | paramagnetic |

| References | [1][2][3][4] |

The mineral pyrite, or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula FeS2 (iron(II) disulfide). Pyrite is considered the most common of the sulfide minerals.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue give it a superficial resemblance to gold, hence the well-known nickname of fool's gold. The color has also led to the nicknames brass, brazzle, and Brazil, primarily used to refer to pyrite found in coal.[5][6]

The name pyrite is derived from the Greek πυρίτης (pyritēs), "of fire" or "in fire",[7] in turn from πύρ (pyr), "fire".[8] In ancient Roman times, this name was applied to several types of stone that would create sparks when struck against steel; Pliny the Elder described one of them as being brassy, almost certainly a reference to what we now call pyrite.[9]

By Georgius Agricola's time, c. 1550, the term had become a generic term for all of the sulfide minerals.[10]

Pyrite is usually found associated with other sulfides or oxides in quartz veins, sedimentary rock, and metamorphic rock, as well as in coal beds and as a replacement mineral in fossils, but has also been identified in the sclerites of scaly-foot gastropods.[11] Despite being nicknamed fool's gold, pyrite is sometimes found in association with small quantities of gold. Gold and arsenic occur as a coupled substitution in the pyrite structure. In the Carlin–type gold deposits, arsenian pyrite contains up to 0.37% gold by weight.[12]

Uses

Pyrite enjoyed brief popularity in the 16th and 17th centuries as a source of ignition in early firearms, most notably the wheellock, where the cock held a lump of pyrite against a circular file to strike the sparks needed to fire the gun.

Pyrite has been used since classical times to manufacture copperas, that is, iron(II) sulfate. Iron pyrite was heaped up and allowed to weather (an example of an early form of heap leaching). The acidic runoff from the heap was then boiled with iron to produce iron sulfate. In the 15th century, new methods of such leaching began to replace the burning of sulfur as a source of sulfuric acid. By the 19th century, it had become the dominant method.[13]

Pyrite remains in commercial use for the production of sulfur dioxide, for use in such applications as the paper industry, and in the manufacture of sulfuric acid. Thermal decomposition of pyrite into FeS (iron(II) sulfide) and elemental sulfur starts at 540 °C; at around 700 °C pS2 is about 1 atm.[14]

A newer commercial use for pyrite is as the cathode material in Energizer brand non-rechargeable lithium batteries.[15]

Pyrite is a semiconductor material with a band gap of 0.95 eV.[16]

During the early years of the 20th century, pyrite was used as a mineral detector in radio receivers, and is still used by crystal radio hobbyists. Until the vacuum tube matured, the crystal detector was the most sensitive and dependable detector available – with considerable variation between mineral types and even individual samples within a particular type of mineral. Pyrite detectors occupied a midway point between galena detectors and the more mechanically complicated perikon mineral pairs. Pyrite detectors can be as sensitive as a modern 1N34A germanium diode detector.[17][18]

Pyrite has been proposed as an abundant, inexpensive material in low-cost photovoltaic solar panels.[19] Synthetic iron sulfide was used with copper sulfide to create the photovoltaic material.[20]

Pyrite is used to make marcasite jewelry. Marcasite jewelry, made from small faceted pieces of pyrite, often set in silver, was known since ancient times and was popular in the Victorian era.[21] At the time when the term became common in jewelry making, "marcasite" referred to all iron sulfides including pyrite, and not to the orthorhombic FeS2 mineral marcasite which is lighter in color, brittle and chemically unstable, and thus not suitable for jewelry making. Marcasite jewelry does not actually contain the mineral marcasite.

China represents the main importing country with an import of around 376,000 tonnes, which resulted at 45% of total global imports. China is also the fastest growing in terms of the unroasted iron pyrites imports, with a CAGR of +27.8% from 2007 to 2016. In value terms, China ($47M) constitutes the largest market for imported unroasted iron pyrites worldwide, making up 65% of global imports.[22]

Formal oxidation states for pyrite, marcasite, and arsenopyrite

From the perspective of classical inorganic chemistry, which assigns formal oxidation states to each atom, pyrite is probably best described as Fe2+S22−. This formalism recognizes that the sulfur atoms in pyrite occur in pairs with clear S–S bonds. These persulfide units can be viewed as derived from hydrogen disulfide, H2S2. Thus pyrite would be more descriptively called iron persulfide, not iron disulfide. In contrast, molybdenite, MoS2, features isolated sulfide (S2−) centers and the oxidation state of molybdenum is Mo4+. The mineral arsenopyrite has the formula FeAsS. Whereas pyrite has S2 subunits, arsenopyrite has [AsS] units, formally derived from deprotonation of H2AsSH. Analysis of classical oxidation states would recommend the description of arsenopyrite as Fe3+[AsS]3−.[23]

Crystallography

Iron-pyrite FeS2 represents the prototype compound of the crystallographic pyrite structure. The structure is simple cubic and was among the first crystal structures solved by X-ray diffraction.[24] It belongs to the crystallographic space group Pa3 and is denoted by the Strukturbericht notation C2. Under thermodynamic standard conditions the lattice constant of stoichiometric iron pyrite FeS2 amounts to 541.87 pm.[25] The unit cell is composed of a Fe face-centered cubic sublattice into which the S ions are embedded. The pyrite structure is also used by other compounds MX2 of transition metals M and chalcogens X = O, S, Se and Te. Also certain dipnictides with X standing for P, As and Sb etc. are known to adopt the pyrite structure.[26]

In the first bonding sphere, the Fe atoms are surrounded by six S nearest neighbours, in a distorted octahedral arrangement. The material is a diamagnetic semiconductor and the Fe ions should be considered to be in a low spin divalent state (as shown by Mössbauer spectroscopy as well as XPS), rather than a tetravalent state as the stoichiometry would suggest.

The positions of X ions in the pyrite structure may be derived from the fluorite structure, starting from a hypothetical Fe2+(S−)2 structure. Whereas F− ions in CaF2 occupy the centre positions of the eight subcubes of the cubic unit cell (1⁄4 1⁄4 1⁄4) etc., the S− ions in FeS2 are shifted from these high symmetry positions along <111> axes to reside on (uuu) and symmetry-equivalent positions. Here, the parameter u should be regarded as a free atomic parameter that takes different values in different pyrite-structure compounds (iron pyrite FeS2: u(S) = 0.385 [27]). The shift from fluorite u = 0.25 to pyrite u = 0.385 is rather large and creates a S-S distance that is clearly a binding one. This is not surprising as in contrast to F− an ion S− is not a closed shell species. It is isoelectronic with a chlorine atom, also undergoing pairing to form Cl2 molecules. Both low spin Fe2+ and the disulfide S22− moeties are closed shell entities, explaining the diamagnetic and semiconducting properties.

The S atoms have bonds with three Fe and one other S atom. The site symmetry at Fe and S positions is accounted for by point symmetry groups C3i and C3, respectively. The missing center of inversion at S lattice sites has important consequences for the crystallographic and physical properties of iron pyrite. These consequences derive from the crystal electric field active at the sulfur lattice site, which causes a polarisation of S ions in the pyrite lattice.[28] The polarisation can be calculated on the basis of higher-order Madelung constants and has to be included in the calculation of the lattice energy by using a generalised Born–Haber cycle. This reflects the fact that the covalent bond in the sulfur pair is inadequately accounted for by a strictly ionic treatment.

Arsenopyrite has a related structure with heteroatomic As-S pairs rather than homoatomic ones. Marcasite also possesses homoatomic anion pairs, but the arrangement of the metal and diatomic anions is different from that of pyrite. Despite its name a chalcopyrite does not contain dianion pairs, but single S2− sulfide anions.

Crystal habit

Pyrite usually forms cuboid crystals, sometimes forming in close association to form raspberry-shaped masses called framboids. However, under certain circumstances, it can form anastamozing filaments or T-shaped crystals.[29] Pyrite can also form almost perfect dodecahedral shapes known as pyritohedra and this suggests an explanation for the artificial geometrical models found in Europe as early as the 5th century BC.[30]

Varieties

Cattierite (Co S2) and vaesite (Ni S2) are similar in their structure and belong also to the pyrite group.

Bravoite is a nickel-cobalt bearing variety of pyrite, with > 50% substitution of Ni2+ for Fe2+ within pyrite. Bravoite is not a formally recognised mineral, and is named after Peruvian scientist Jose J. Bravo (1874–1928).[31]

Distinguishing similar minerals

It is distinguishable from native gold by its hardness, brittleness and crystal form. Natural gold tends to be anhedral (irregularly shaped), whereas pyrite comes as either cubes or multifaceted crystals. Pyrite can often be distinguished by the striations which, in many cases, can be seen on its surface. Chalcopyrite is brighter yellow with a greenish hue when wet and is softer (3.5–4 on Mohs' scale).[32] Arsenopyrite is silver white and does not become more yellow when wet.

Hazards

Iron pyrite is unstable at Earth's surface: iron pyrite exposed to air and water decomposes into iron oxides and sulfate. This process is hastened by the action of Acidithiobacillus bacteria which oxidize the pyrite to produce ferrous iron and sulfate. These reactions occur more rapidly when the pyrite is in fine crystals and dust, which is the form it takes in most mining operations.

Acid drainage

Sulfate released from decomposing pyrite combines with water, producing sulfuric acid, leading to acid rock drainage. An example of acid rock drainage caused by pyrite is the 2015 Gold King Mine waste water spill.

Dust explosions

Pyrite oxidation is sufficiently exothermic that underground coal mines in high-sulfur coal seams have occasionally had serious problems with spontaneous combustion in the mined-out areas of the mine. The solution is to hermetically seal the mined-out areas to exclude oxygen.

In modern coal mines, limestone dust is sprayed onto the exposed coal surfaces to reduce the hazard of dust explosions. This has the secondary benefit of neutralizing the acid released by pyrite oxidation and therefore slowing the oxidation cycle described above, thus reducing the likelihood of spontaneous combustion. In the long term, however, oxidation continues, and the hydrated sulfates formed may exert crystallization pressure that can expand cracks in the rock and lead eventually to roof fall.[33]

Weakened building materials

Building stone containing pyrite tends to stain brown as the pyrite oxidizes. This problem appears to be significantly worse if any marcasite is present.[34] The presence of pyrite in the aggregate used to make concrete can lead to severe deterioration as the pyrite oxidizes.[35] In early 2009, problems with Chinese drywall imported into the United States after Hurricane Katrina were attributed to oxidation of pyrite, which releases hydrogen sulfide gas. These problems included a foul odor and corrosion of copper wiring.[36] In the United States, in Canada,[37] and more recently in Ireland,[38][39][40] where it was used as underfloor infill, pyrite contamination has caused major structural damage. Modern tests for aggregate materials[41] certify such materials as free of pyrite.

Pyritised fossils

Pyrite and marcasite commonly occur as replacement pseudomorphs after fossils in black shale and other sedimentary rocks formed under reducing environmental conditions.[42] However, pyrite dollars or pyrite suns which have an appearance similar to sand dollars are pseudofossils and lack the pentagonal symmetry of the animal.

Images

As a replacement mineral in an ammonite from France

As a replacement mineral in an ammonite from France Pyrite from Ampliación a Victoria Mine, Navajún, La Rioja, Spain

Pyrite from Ampliación a Victoria Mine, Navajún, La Rioja, Spain Pyrite from the Sweet Home Mine, with golden striated cubes intergrown with minor tetrahedrite, on a bed of transparent quartz needles

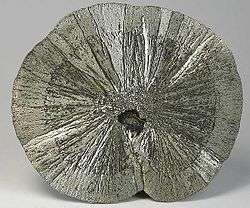

Pyrite from the Sweet Home Mine, with golden striated cubes intergrown with minor tetrahedrite, on a bed of transparent quartz needles Radiating form of pyrite

Radiating form of pyrite Paraspirifer bownockeri in pyrite

Paraspirifer bownockeri in pyrite Pink fluorite perched between pyrite on one side and metallic galena on the other side

Pink fluorite perched between pyrite on one side and metallic galena on the other side

References

- ↑ Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20th ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 285–286. ISBN 978-0-471-80580-9.

- ↑ "Pyrite". Webmineral.com. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

- ↑ "Pyrite". Mindat.org. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

- ↑ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W. and Nichols, Monte C., ed. (1990). "Pyrite" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Volume I (Elements, Sulfides, Sulfosalts). Chantilly, VA, US: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 978-0962209734.

- ↑ Jackson, Julia A.; Mehl, James; Neuendorf, Klaus (2005). Glossary of Geology. American Geological Institute. p. 82. ISBN 9780922152766 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Fay, Albert H. (1920). A Glossary of the Mining and Mineral Industry. United States Bureau of Mines. pp. 103–104 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Henry George Liddell; Robert Scott (eds.). "πυρίτης". A Greek-English Lexicon. Tufts University – via Perseus.

- ↑ Henry George Liddell; Robert Scott (eds.). "πύρ". A Greek-English Lexicon. Tufts University – via Perseus.

- ↑ Dana, James Dwight; Dana, Edward Salisbury (1911). Descriptive Mineralogy (6th ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 86.

- ↑ "De re metallica". The Mining Magazine. Translated by Hoover, H.C.; Hoover, L.H. London: Dover. 1950 [1912]. see footnote on p. 112.

- ↑ "Armor-plated snail discovered in deep sea". news.nationalgeographic.com. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ↑ Fleet, M. E.; Mumin, A. Hamid (1997). "Gold-bearing arsenian pyrite and marcasite and arsenopyrite from Carlin Trend gold deposits and laboratory synthesis" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 82: 182–193.

- ↑ "Industrial England in the Middle of the Eighteenth Century". Nature. 83 (2113): 264–268. 1910-04-28. Bibcode:1910Natur..83..264.. doi:10.1038/083264a0.

- ↑ Rosenqvist, Terkel (2004). Principles of extractive metallurgy (2nd ed.). Tapir Academic Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-82-519-1922-7.

- ↑ "Cylindrical Primary Lithium [battery]". Lithium-Iron Disulfide (Li-FeS2) (PDF). Handbook and Application Manual. Energizer Corporation. 2017-09-19. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- ↑ Ellmer, K. & Tributsch, H. (2000-03-11). "Iron Disulfide (Pyrite) as Photovoltaic Material: Problems and Opportunities". Proceedings of the 12th Workshop on Quantum Solar Energy Conversion – (QUANTSOL 2000). Archived from the original on 2010-01-15.

- ↑ The Principles Underlying Radio Communication. U.S. Army Signal Corps. Radio Pamphlet. 40. 1918. section 179, pp. 302–305 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Thomas H. Lee (2004). The Design of Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 4–6. ISBN 9780521835398 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Wadia, Cyrus; Alivisatos, A. Paul; Kammen, Daniel M. (2009). "Materials availability expands the opportunity for large-scale photovoltaics deployment". Environmental Science & Technology. 43 (6): 2072–7. Bibcode:2009EnST...43.2072W. doi:10.1021/es8019534. PMID 19368216.

- ↑ Sanders, Robert (17 February 2009). "Cheaper materials could be key to low-cost solar cells". Berkeley, CA: University of California – Berkeley.

- ↑ Hesse, Rayner W. (2007). Jewelrymaking Through History: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-313-33507-5.

- ↑ "Which Country Imports the Most Unroasted Iron Pyrites in the World? – IndexBox". www.indexbox.io. Retrieved 2018-09-11.

- ↑ Vaughan, D. J.; Craig, J. R. (1978). Mineral Chemistry of Metal Sulfides. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-21489-6.

- ↑ Bragg, W. L. (1913). "The structure of some crystals as indicated by their diffraction of X-rays". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 89 (610): 248–277. Bibcode:1913RSPSA..89..248B. doi:10.1098/rspa.1913.0083. JSTOR 93488.

- ↑ Birkholz, M.; Fiechter, S.; Hartmann, A.; Tributsch, H. (1991). "Sulfur deficiency in iron pyrite (FeS2−x) and its consequences for band structure models". Physical Review B. 43 (14): 11926–11936. Bibcode:1991PhRvB..4311926B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.43.11926.

- ↑ Brese, Nathaniel E.; von Schnering, Hans Georg (1994). "Bonding Trends in Pyrites and a Reinvestigation of the Structure of PdAs2, PdSb2, PtSb2 and PtBi2". Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 620 (3): 393–404. doi:10.1002/zaac.19946200302.

- ↑ Stevens, E. D.; Delucia, M. L.; Coppens, P. (1980). "Experimental observation of the Effect of Crystal Field Splitting on the Electron Density Distribution of Iron Pyrite". Inorg. Chem. 19 (4): 813–820. doi:10.1021/ic50206a006.

- ↑ Birkholz, M. (1992). "The crystal energy of pyrite". J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 4 (29): 6227–6240. Bibcode:1992JPCM....4.6227B. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/4/29/007.

- ↑ Bonev, I. K.; Garcia-Ruiz, J. M.; Atanassova, R.; Otalora, F.; Petrussenko, S. (2005). "Genesis of filamentary pyrite associated with calcite crystals". European Journal of Mineralogy. 17 (6): 905–913. Bibcode:2005EJMin..17..905B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.378.3304. doi:10.1127/0935-1221/2005/0017-0905.

- ↑ The pyritohedral form is described as a dodecahedron with pyritohedral symmetry; Dana J. et al., (1944), System of mineralogy, New York, p 282

- ↑ Mindat – bravoite. Mindat.org (2011-05-18). Retrieved on 2011-05-25.

- ↑ Pyrite on. Minerals.net (2011-02-23). Retrieved on 2011-05-25.

- ↑ Zodrow, E (2005). "Colliery and surface hazards through coal-pyrite oxidation (Pennsylvanian Sydney Coalfield, Nova Scotia, Canada)". International Journal of Coal Geology. 64: 145–155. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2005.03.013.

- ↑ Bowles, Oliver (1918) The Structural and Ornamental Stones of Minnesota. Bulletin 663, United States Geological Survey, Washington. p. 25.

- ↑ Tagnithamou, A; Sariccoric, M; Rivard, P (2005). "Internal deterioration of concrete by the oxidation of pyrrhotitic aggregates". Cement and Concrete Research. 35: 99–107. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.06.030.

- ↑ Angelo, William (28 January 2009) A Material Odor Mystery Over Foul-Smelling Drywall. Engineering News-Record.

- ↑ "PYRITE and Your House, What Home-Owners Should Know Archived 2012-01-06 at the Wayback Machine." – ISBN 2-922677-01-X – Legal deposit – National Library of Canada, May 2000

- ↑ Shrimer, F. and Bromley, AV (2012) "Pyritic Heave in Ireland". Proceedings of the Euroseminar on Building Materials. International Cement Microscopy Association (Halle Germany)

- ↑ Homeowners in protest over pyrite damage to houses. The Irish Times (11 June 2011

- ↑ Brennan, Michael (22 February 2010) Devastating 'pyrite epidemic' hits 20,000 newly built houses. Irish Independent

- ↑ I.S. EN 13242:2002 Aggregates for unbound and hydraulically bound materials for use in civil engineering work and road construction

- ↑ Briggs, D. E. G.; Raiswell, R.; Bottrell, S. H.; Hatfield, D.; Bartels, C. (1996-06-01). "Controls on the pyritization of exceptionally preserved fossils; an analysis of the Lower Devonian Hunsrueck Slate of Germany". American Journal of Science. 296 (6): 633–663. Bibcode:1996AmJS..296..633B. doi:10.2475/ajs.296.6.633. ISSN 0002-9599.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyrite. |

- Educational article about the famous pyrite crystals from the Navajun Mine

- How Minerals Form and Change "Pyrite oxidation under room conditions".

- Poliakoff, Martyn (2009). "Fool's Gold". The Periodic Table of Videos. University of Nottingham.