Institutional Revolutionary Party

Institutional Revolutionary Party Partido Revolucionario Institucional | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Chairperson | Claudia Ruiz Massieu |

| General Secretary | Rubén Moreira Valdez |

| Founded |

4 March 1929 (as PNR) 30 March 1938 (as PRM) 18 January 1946 (as PRI) |

| Headquarters |

Av. Insurgentes Norte 59 col. Buenavista 06359 Cuauhtémoc, Mexico City |

| Newspaper | La República |

| Youth wing | Red Jóvenes x México |

| Labor wing | Confederation of Mexican Workers |

| Ideology |

Revolutionary nationalism[1][2][3] Constitutionalism[4][5][6] Technocracy[7] |

| Political position | Centre[8][9][10] |

| National affiliation | Todos por México |

| Continental affiliation | COPPPAL |

| International affiliation | Socialist International[11] |

| Colours | Green, white, red |

| Seats in the Chamber of Deputies |

47 / 500 |

| Seats in the Senate |

14 / 128 |

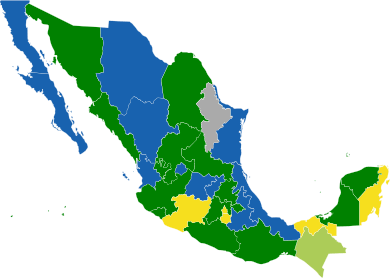

| Governorships |

12 / 32 |

| Seats in State legislatures |

361 / 1,124 |

| Website | |

|

pri | |

The Institutional Revolutionary Party (Spanish: Partido Revolucionario Institucional, PRI) is a Mexican political party founded in 1929 that held uninterrupted power in the country for 71 years from 1929 to 2000, first as the National Revolutionary Party (Spanish: Partido Nacional Revolucionario, PNR), then as the Party of the Mexican Revolution (Spanish: Partido de la Revolución Mexicana, PRM), and finally renaming itself as the Institutional Revolutionary Party in 1946.

The National Revolutionary Party was founded in 1929 by Plutarco Elías Calles, Mexico's paramount leader at the time and self-proclaimed "Jefe Máximo" (Maximum Chief) of the Mexican Revolution. The party was created with the intent of providing a political space in which all the surviving leaders and combatants of the Mexican Revolution could participate, and to solve the grave political crisis caused by the assassination of president-elect Álvaro Obregón in 1928. Although Calles himself fell into political disgrace and was exiled in 1936, the party continued ruling Mexico until 2000, changing names twice until it became the Institutional Revolutionary Party.

Throughout its nine-decade existence, the PRI has adopted a very wide array of ideologies (often determined by the President of the Republic in turn). In the 1980s, the party went through reforms that shaped its current incarnation, with policies characterized as centre-right, such as the privatization of State-run companies, closer relations with the Catholic church, and embracing free-market capitalism.[12][13][14] At the same time, the left-wing members of the party abandoned the PRI and founded the Party of the Democratic Revolution (Partido de la Revolución Democrática, PRD) in 1989.

Though it is a full member of the Socialist International (along with its rival, the left-wing PRD; Mexico is one of the few nations with two major, competing parties that are part of the same international grouping),[11] the PRI is not considered a social democratic party in the traditional sense.

The adherents of the PRI party are known in Mexico as "Priístas" and the party is nicknamed "El tricolor" (The tricolor) because of its use of the Mexican national colors of green, white and red, as found on the Mexican flag.

Overview

Profile

The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) is described by some scholars as a "state party",[13][15] a term which captures both the non-competitive history and character of the party itself, and the inextricable connection between the party and the Mexican nation-state for much of the 20th century. In 1990, Peruvian Nobel Prize laureate for literature, Mario Vargas Llosa, called the uninterrupted Mexican government under the PRI la dictadura perfecta ("the perfect dictatorship").[16]

The PRI has been criticized for using the colors of the national flag in its logo, something considered not unreasonable in many countries, but frowned upon in Mexico, while there is no law that forbids this act.

According to the Statesman Journal, for more than seven decades, the PRI ran Mexico under an "autocratic, endemically corrupt, crony-ridden government". The elites of the PRI ruled the police and the judicial system, and justice was only available if purchased with bribes.[17] During its time in power, the PRI became a symbol of corruption, repression, economic mismanagement, and electoral fraud; many educated Mexicans and urban dwellers worried that its return could signify a return to Mexico's past.[18]

Meaning of the name

At first glance, the PRI's name looks like a confusing oxymoron or paradox to speakers of English, for they normally associate the term "revolution" with the destruction of "institutions".[19] As Rubén Gallo has explained, the Mexican concept of institutionalizing the Revolution simply refers to the corporatist nature of the PRI—that is, the PRI subsumed the "disruptive energy" of the Revolution (and thereby ensured its own longevity) by co-opting and incorporating its enemies into its bureaucratic government as new institutional sectors.[19]

Early history and former names

The political party went through two names before settling into its third and current name.

PNR (1929–1938)

Even though the armed phase of the Mexican Revolution had ended in 1920, Mexico continued to encounter political unrest. A grave political crisis caused by the 1928 assassination of president-elect Álvaro Obregón led to the founding in 1929 of the National Revolutionary Party (Spanish: Partido Nacional Revolucionario, PNR) by Plutarco Elías Calles, Mexico's president from 1924 to 1928.

The intent was to institutionalize the agreed result of the Mexican Revolution. The party was established as the result of Calles' efforts to stop the violent struggle for power between the victorious factions of the Revolution, and to guarantee the peaceful transmission of power for members of the party; in the first years of the party's existence, the PNR was the only political machine in existence. During this period, known as Maximato (named after the title Calles gave himself as "Maximum Chief of the Revolution"), Calles remained the dominant leader of the country and continued exercising power behind the Presidential Seat. The successive presidents of this period, Emilio Portes Gil, Pascual Ortiz Rubio and Abelardo L. Rodríguez, were in practice subordinates of Calles.

PRM (1938–1946)

This ended with the election to the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas, a candidate handpicked by the liberal PNR leaders.[20] Though the now strongly conservative Calles thought he could control him,[20] it quickly became clear Cárdenas would not accept a subordinate role like his predecessors did.[20] After establishing himself in the presidency, Cárdenas had Calles and dozens of his corrupt associates arrested, or deported to the United States, in 1936. Cárdenas became perhaps Mexico's most popular 20th-century president, most renowned for expropriating the oil interests of the United States and European petroleum companies in the run-up to World War II. He was a person of leftist ideas who nationalized different industries, provided many social institutions that were popular with the Mexican people, and had the party renamed as the "Party of the Mexican Revolution" (PRM).

In 1938, Cárdenas reorganized the party as the Party of the Mexican Revolution (Spanish: Partido de la Revolución Mexicana, PRM) whose aim was to establish a democracy of workers and socialism.[21] However, this was never achieved and his main intention was to create the broad-based political alliances necessary for the PRI's long-term survival, splitting the party into mass organizations representing different interest groups and acting as the political consciousness of the country in a more realistic level (for example, the Confidential National, the farmer's group). His strategy with the party mirrored the balanced ticket approach of 1930s Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak, characteristic of Chicago by balancing ethnic interests. Settling disputes and power struggles within the party structure helped prevent congressional gridlock and possible armed rebellions, but this style of dispute resolution also created a "rubber stamp" legislative apparatus.

PRI (1946 – present)

Current name

| ||||||||

Cárdenas's successor Manuel Ávila Camacho gave the party its present name in 1946.[22] The party, under its three different names, held every political position until 1946 when the PAN started winning posts for municipal president and federal deputies and senators, starting in 1946, after the party changed its name to its current name, the Institutional Revolutionary Party. By then, the party had acquired a reputation for corruption, and while this was admitted (to a degree) by some of its affiliates, its supporters maintained that the role of the party was crucial in the modernization and stabilization of Mexico.

Despite the emergence of the PAN, the PRI won every presidential election from 1929 to 1982, by well over 70 percent of the vote—margins that were usually obtained by massive electoral frauds. Toward the end of his term, the incumbent president in consultation with party leaders, selected the PRI's candidate in the next election in a procedure known as "the tap of the finger" (Spanish: el dedazo), which was integral in the continued success of the PRI towards the end of the 20th century. In essence, given the PRI's overwhelming dominance, the president chose his successor. The PRI's dominance was near-absolute at all other levels as well. It held an overwhelming majority in the Chamber of Deputies, as well as every seat in the Senate and every state governorship.

The "Mexican Miracle"

The first four decades of PRI administration have been dubbed the "Mexican Miracle", a period of economic growth fueled by import substitution and low inflation. From 1940 to 1970 GDP increased sixfold while the population only doubled,[23] and peso-dollar parity was maintained at a stable exchange rate.

Economic nationalist and protectionist policies implemented in the 1930s effectively closed off Mexico to foreign trade and speculation, so that the economy was fueled primarily by state investment and businesses were heavily reliant on government contracts. As a result of these policies, Mexico's capitalist impulses were channeled into massive industrial development and social welfare programs, which helped to urbanize the mostly-agrarian country, funded generous welfare subsidies for the working class, and fueled considerable advances in communication and transportation infrastructure. This period of commercial growth created a significant urban middle class of white-collar bureaucrats and office workers, and allowed high-ranking PRI officials to graft large personal fortunes through their control over state-funded programs. State monopoly over key industries like electricity and telecommunication allowed a small clique of businessmen to dominate their sectors of the economy by supplying government-owned companies with goods and commodities.

Despite the party's pervasive corruption, the general economic prosperity served to legitimize PRI hegemony in the eyes of most Mexicans, and for decades the party faced no real opposition on any level of government. On the rare occasions when an opposition candidate (usually from the conservative National Action Party) garnered a majority of votes in an election, the PRI often used its control of local government to rig the results in its favor. The PRI co-opted criticism by incorporating all classes of society into its hierarchy; PRI-controlled labor unions maintained a tight grip over the working classes, the PRI held rural farmers in check through its control of the ejidos (state-owned plots of land that peasants could farm but not own), and generous financial support of universities and the arts ensured that most intellectuals rarely challenged the ideals of the Mexican Revolution. In this way, PRI rule was supported by a broad national consensus that held firm for decades, even as polarizing forces gradually worked to divide the nation in preparation for the crises of the 1970s and 80s.[24]

Tlatelolco massacre of 1968

The improvement of the economy had a disparate impact in different social sectors and discontent started growing within the low classes. In 1968 Mexico City became the first city in the Spanish-speaking world to be chosen to host an Olympic Games. Using the international focus on the country, students at the National Mexican Autonomous University (UNAM) protested the lack of democracy and social justice. President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz (1964–1970) ordered the army to occupy the university to suppress the revolt and minimize the disruption of the Olympic Games. On October 2, 1968, student groups demanding the withdrawal of the IPN protested at the Plaza de las Tres Culturas. Unaccustomed to this type of protest, the Mexican government made an unusual move by asking the United States for assistance, through LITEMPO, a spy-program to inform the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the US to obtain information from Mexico. The CIA responded by sending military radios, weapons and ammunition.[25] The LITEMPO had previously provided the Díaz Ordaz government with 1,000 rounds of .223 Remington ammunition in 1963.[26] During the protests shots were fired and a number of students died (officially 39, although hundreds are claimed) and hundreds were arrested. The President of the Olympic Committee then declared that the protests were against the government and not the Olympics so the games proceeded.[27]

Economic crisis of the 1970s

By the late 1960s, fundamental issues were emerging in the two principal sectors of Mexico's economy. Regional underdevelopment, technological shortages, lack of foreign competition, and uneven distribution of wealth led to chronic underproduction of investment and capital goods, putting the long-term future of Mexican industry in doubt. Meanwhile, ubiquitous poverty combined with a dearth of agricultural investment and infrastructure caused continuous migration from rural to urban areas; in 1971, Mexican agriculture was in such a state that the country had become a net importer of food. An associated decline in the tourism industry (which had previously compensated for failures in industry and agriculture) meant that by the early 1970s, the economy had begun to falter, and the only sure source of capital was external borrowing.[28]

Díaz Ordaz chose his Government Secretary, Luis Echeverría, to succeed him as President. Echeverría's administration (1970–76) increased social spending, through external debt, at a time when oil production and prices were surging. However, the growth of the economy came accompanied by inflation and then by a plummeting of oil prices and increases in interest rates. Investment started fleeing the country and the peso became overvalued, to prevent a devaluation and further fleeing of investments, the Bank of Mexico borrowed 360 million dollars from the Federal Reserve with the promise of stabilizing the economy. External debt reached the level of $25 billion.[29] Unable to contain the fleeing of dollars, Echeverría allowed the peso to float for the first time on August 31, 1976, then again later and the peso lost half of its value.[29] Echeverría designated José López Portillo, his Secretary of Finance, as his successor for the term 1976-82, hoping that the new administration would have a tighter control on inflation and to preserve political unity.[29]

During his campaign, López Portillo promised to defend the peso "como un perro" ("like a dog"),[30] López Portillo refused to devalue the currency[29] saying "The president who devalues, devalues himself."[30] The discovery of significant oil sites in Tabasco and Campeche helped the economy to recover and López Portillo promised to "administer the abundance." The development of the promising oil industry was financed through external debt which reached 59 billion dollars[30] (compared to 25 billion[29] during Echeverría). Oil production increased from 94,000 barrels per day (14,900 m3/d) at the beginning of his administration to 1,500,000 barrels per day (240,000 m3/d) at the end of his administration and Mexico became the fourth largest oil producer in the world.[30] The price for a barrel of oil also increased from three dollars in 1970 to 35 dollars in 1981.[30]

The government attempted to develop heavy industry. However, waste became the rule as centralized resource allocation and distribution systems were accompanied by inefficiently located factories incurring high transport costs.

Mexico increased its international presence during López Portillo: in addition to becoming the world's fourth oil exporter, Mexico restarted relations with the post Franco-Spain in 1977, allowed Pope John Paul II to visit Mexico, welcomed American president Jimmy Carter and broke relations with Somoza and supported the Sandinista National Liberation Front in its rebellion against the United States supported government. López Portillo also proposed the Plan Mundial de Energéticos in 1979 and summoned a North-South World Summit in Cancún in 1981 to seek solutions to social problems.[30] In 1979, the PRI founded the COPPPAL, the Permanent Conference of Political Parties of Latin America and the Caribbean, an organization created "to defend democracy and all lawful political institutions and to support their development and improvement to strengthen the principle of self determination of the peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean".[31]

López Portillo also freed political prisoners and proposed a reform called Ley Federal de Organizaciones Políticas y Procesos Electorales which gave official registry to opposition groups such as the Mexican Democratic Party and the Mexican Communist Party. This law also created positions in the lower chamber of congress for opposition parties through proportionality of votes, relative majority, uninominal and plurinominal. As a result, in 1979, the first independent (non-PRI) communist deputies were elected to the Congress of Mexico.[30]

Social programs were also created through the Alliance for Production, Global Development Plan, el COPLAMAR, Mexican Nourishing System, to attain independence on food, to reform public administration. López Portillo also created the secretaries of Programming and Budgeting, Agriculture and Water Resources, Industrial Support, Fisheries and Human Settlements and Public Works. Mexico then obtained high economic growth, a recuperation of salaries and an increase in spending on education and infrastructure. This way, social and regional inequalities started to diminish.[30]

All this prosperity ended when the over-supply of oil in early 1982 caused oil prices to plummet and damaged severely the national economy. Interest rates skyrocketed in 1981 and external debt reached 86 billion dollars and exchange rates went from 26 to 70 pesos per dollar and inflation of 100%. This situation became so desperate that Lopez-Portillo ordered the suspension on payments of external debt and the nationalization of the banking industry in 1982 consistent with the Socialist goals of the PRI. Capital fled Mexico at a rate never seen before in history. The Mexican government provided subsidies to staple food products and rail travel; this diminished the consequences of the crises on the populace. Job growth stagnated and millions of people migrate North to escape the economic stagnation. López Portillo's reputation plummeted and his character became the butt of jokes from the press.[30]

The attempted industrialization had not been responsive to consumer needs. Therefore, unprecedented urbanization and overcrowding followed and so, substandard pre-fabricated apartment blocs had to be built in large cities.

Miguel de la Madrid was the first of a series of economists to rule the country, a technocrat who started to implement neoliberal reforms, causing the number of state-owned industries to decline from 1155 to a mere 412. After the 1982 default, crisis lenders were unwilling to loan Mexico and this resulted in currency devaluations to finance spending. An earthquake in September 1985, in which his administration was criticised for its slow and clumsy reaction, added more woe to the problems. As a result of the crisis, black markets supplied by goods stolen from the public sector appeared. Galloping inflation continued to plague the country, hitting a record high in 1987 at 159.2%.

Left-wing splits from the PRI

In 1986, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas (former Governor of Michoacán and son of the former president of Mexico Lázaro Cárdenas) formed the "Democratic Current" (Spanish: Corriente Democrática) of the PRI, which criticized the federal government for reducing spending on social programs to increase payments on foreign debt. The members of the Democratic Current were expelled from the party and formed the National Democratic Front (FDN, Spanish: Frente Democrático Nacional) in 1987. The following year, the FDN elected Cárdenas as presidential candidate for the 1988 presidential election[32] which was won by Carlos Salinas de Gortari, obtaining 50.89% of the votes (according to official figures) versus 32% of Cárdenas. The official results were delayed, with the Secretary of the Interior (until then, the organizer of elections) blaming it on a computer system failure. Cárdenas, who claimed to have won and claimed such computer failure was caused by a manipulation of the system to count votes. Manuel Clouthier of the National Action Party (Mexico) also claimed to have won, although not as vocally.

Miguel de la Madrid, Mexico's president at the time of the 1988 election, admitted in 2004 that, on the evening of the election, he received news that Cárdenas was going to win by a majority, and that he and others rigged the election as a result.[33]

Clouthier, Cárdenas and Rosario Ibarra de Piedra then complained before the building of the Secretary of the Interior.[34] Clouthier and his followers then set up other protests, among them one at the Chamber of Deputies, demanding that the electoral packages be opened. In 1989, Clouthier presented an alternative cabinet (a British style Shadow Cabinet) with Diego Fernández de Cevallos, Jesús González Schmal, Fernando Canales Clariond, Francisco Villarreal Torres, Rogelio Sada Zambrano, María Elena Álvarez Bernal, Moisés Canales, Vicente Fox, Carlos Castillo Peraza and Luis Felipe Bravo Mena as cabinet members and Clouthier as cabinet coordinator. The purpose of this cabinet was to vigilate the actions of the government. Clouthier died next October in an accident with Javier Calvo, a federal deputy. The accident has been claimed by the PAN as a state assassination since then.[35] That same year, the PRI lost its first state government with the election of Ernesto Ruffo Appel as governor of Baja California.

Assassination of Luis Donaldo Colosio, loss of majority in Congress and decline of power

In 1990, Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa called the government under the PRI la dictadura perfecta ("the perfect dictatorship").[16] In 1994, for the first time since the revolution, a presidential candidate was murdered, Luis Donaldo Colosio Murrieta. His campaign director, Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de Leon, was subsequently elected in the first presidential election monitored by international observers. A number of factors, including the 1994 economic crisis in Mexico, caused the PRI to lose its absolute majority in both chambers of the federal congress for the first time in 1997.

After several decades in power the PRI had become a symbol of corruption and electoral fraud.[36] The conservative National Action Party (PAN) became a stronger party after 1976 when it obtained the support from businessmen after recurring economic crises.[36] Consequently, the PRI's left wing separated and formed its own party, the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) in 1989.

Critics claim electoral fraud, with voter suppression and violence, was used when the political machine did not work and elections were just a ritual to simulate the appearance of a democracy. However, the three major parties now make the same claim against each other (PRD against Vicente Fox's PAN and PAN vs. López Obrador's PRD, and the PRI against the PAN at the local level and local elections such as the Yucatán state election, 2007). Two other PRI presidents Miguel de la Madrid and Carlos Salinas de Gortari privatized many outmoded industries, including banks and businesses, entered the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and also negotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Greater economic stability since the last major economic crisis in Mexico (the 1995 peso crisis) was achieved in great part through economic reforms begun under Ernesto Zedillo, who was the last successive PRI-nominated president to serve since the Mexican Revolution, and whose tenure commenced just as the peso crisis was coming to a head. Subsequent administrations maintained stability with continued assistance from PRI members such as Secretary of Finance Francisco Gil Diaz and Bank of Mexico Governor Guillermo Ortiz.

Loss of the presidency of Mexico

Prior to the 2000 general elections, the PRI held its first primaries to elect the party's presidential candidate. The primary candidates, nicknamed "los cuatro fantásticos" (Spanish for The Fantastic Four), were:[37]

- Francisco Labastida Ochoa (former governor of Sinaloa and Secretary of the Interior)

- Roberto Madrazo Pintado (former governor of Tabasco)

- Manuel Bartlett (former governor of Puebla and Secretary of the Interior)

- Humberto Roque Villanueva

The favorites in the primaries were Labastida and Madrazo, and the latter initiated a campaign against the first, perceived as Zedillo's candidate since many former secretaries of the interior were chosen as candidates by the president. His campaign, produced by prominent publicist Carlos Alazraki, had the motto "Dale un Madrazo al dedazo" or "Give a Madrazo to the dedazo" with "madrazo" being an offensive slang term for a "strike" and "dedazo" a slang used to describe the unilaterally choosing of candidates by the president (literally "finger-strike").

The growth of the PAN and PRD parties culminated in 2000, when the PAN won the presidency, and again in 2006 (won this time by the PAN with a small margin over the PRD.) Many prominent members of the PAN (Manuel Clouthier,[35] Addy Joaquín Coldwell and Demetrio Sodi), most of the PRD (most notably all three Mexico City mayors Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas and Marcelo Ebrard), the PVEM (Jorge González Torres) and New Alliance (Roberto Campa) were once members of the PRI, including many presidential candidates from the opposition (Clouthier, López Obrador, Cárdenas, González Torres, Campa and Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, among many others).

In the presidential elections of July 2, 2000, its candidate Francisco Labastida Ochoa was defeated by Vicente Fox, after getting only 36.1% of the popular vote. It was to be the first Presidential electoral defeat of the PRI. In the senatorial elections of the same date, the party won with 38.1%, or 33 out of 128 seats in the Senate of Mexico.

As an opposition party

After much restructuring, the party was able to make a recovery, winning the greatest number of seats (5% short of a true majority) in Congress in 2003: at these elections, the party won 224 out of 500 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, remaining as the largest single party in both the Chamber of Deputies and Senate. In the Federal District the PRI obtained only one borough mayorship (jefe delegacional) out of 16, and no first-past-the-post members of the city assembly. The PRI recouped some significant losses on the state level (most notably, the governorship of former PAN stronghold Nuevo León). On August 6, 2004, in two closely contested elections in Oaxaca and Tijuana, PRI candidates Ulises Ruiz Ortiz and Jorge Hank Rhon won the races for the governorship and municipal presidency respectively. The PAN had held control of the president's office of the municipality of Tijuana for 15 years. Six out of eight gubernatorial elections held during 2005 were won by the PRI: Quintana Roo, Hidalgo, Colima, Estado de México, Nayarit, and Coahuila. The PRI then controlled the states on the country's northern border with the US except for Baja California.

Later that year Roberto Madrazo, president of the PRI, left his post to seek a nomination as the party's candidate in the 2006 presidential election. According to the statutes, the presidency of the party would then go to Elba Esther Gordillo as party secretary. The rivalry between Madrazo and Gordillo caused Mariano Palacios Alcocer instead to become president of the party, (Elba Esther Gordillo would later on be declared a criminal and arrested in 2013.).[38] After what was perceived an imposition of Madrazo as candidate a group was formed called Unidad Democrática (Spanish: "Democratic Unity"), although nicknamed Todos Unidos Contra Madrazo (Spanish: "Everybody United Against Madrazo" or "TUCOM")[39] which was formed by governors and former state governors:

- Arturo Montiel (former governor of the State of Mexico)

- Enrique Jackson (federal senator)

- Tomás Yarrington (governor of Tamaulipas)

- Note: Yarrington is currently facing a prison sentence after being sentenced by the Mexican Government, and the United States Government for proven crimes related to drug traffic and money laundering committed during his tenure as governor,[40][41] the PRI has issued an apology and expelled him from their political party.[42]

- Enrique Martínez (former governor of Coahuila)

- Manuel Núñez (governor of Hidalgo)

Montiel won the right to run against Madrazo for the candidacy but withdrew when it was made public that he and his French wife had multi-million properties in Europe.[43] Madrazo and Everardo Moreno contended in the primaries which was won by the first.[44] Madrazo then represented the PRI and the Ecologist Green Party of Mexico (PVEM) in the Alliance for Mexico coalition.

During his campaign Madrazo declared that the PRI and PRD were "first cousins", to this Emilio Chuayffet Chemor responded that if that was the case then Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), candidate of the PRD would also be a first cousin and he might win the election.[45]

AMLO was, by then, the favorite in the polls, with many followers within the PRI. Madrazo, second at the polls, then released TV spots against AMLO with little success, his campaign was managed again by Alazraki. Felipe Calderón ran a more successful campaign and then tied with Madrazo and later surpassed him as the second favorite. Gordillo, also the teachers' union leader, resentful against Madrazo, helped a group of teachers constitute the New Alliance Party. Divisions within the party and a successful campaign of the PAN candidate caused Madrazo to fall to third place. The winner, as announced by the Federal Electoral Institute and valuated by the Mexican Election Tribunal amidst a controversy, was Felipe Calderón of the ruling PAN. On November 20 of the same year, a group of young PRI politicians launched a movement that is set to reform and revolutionize the party.[46] The PRI candidate failed to win a single state in the 2006 presidential election.

In the 2006 legislative elections the party won 106 out of 500 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 35 out of 128 Senators.

In 2007 the PRI re-gained the governorship of Yucatán and was the party with the most mayorships and state congresspeople in the elections in Yucatán (tying with the PAN in the number of deputies), Chihuahua, Durango, Aguascalientes, Veracruz, Chiapas and Oaxaca. The PRI obtained the most mayorships in Zacatecas and the second most deputies in the congressional elections of Zacatecas and Baja California.[47]

In 2009, the PRI re-gained plurality control of Mexican congress. This is the first time congress will be controlled by the PRI since the first initial victory by the opposing party PAN in the year 2000.[48]

Return of the PRI

Under Enrique Peña Nieto and after ruling for most of the past century in Mexico, the PRI returned to the presidency as it had brought hopes to those who gave the PRI another chance and fear to those who worry about the old PRI tactics of making deals with the cartels in exchange for relative peace.[49] According to an article published by The Economist on June 23, 2012, part of the reason why Peña Nieto and the PRI were voted back to the presidency after a 12-year struggle lies in the disappointment of the ruling of the PAN.[50] Buffeted by China's economic growth and the economic recession in the United States, the annual growth of Mexico's economy between 2000 and 2012 was 1.8%. Poverty exacerbated, and without a ruling majority in Congress, the PAN presidents were unable to pass structural reforms, leaving monopolies and Mexico's educational system unchanged.[50] In 2006, Felipe Calderón chose to make the battle against organized crime the centerpiece of his presidency. Nonetheless, with over 60,000 dead and a lack of any real progress, Mexican citizens became tired of a fight they had first supported, and not by majority.[50] The Economist alleged that these signs are "not as bad as they look," since Mexico is more democratic, it enjoys a competitive export market, has a well-run economy despite the crisis, and there are tentative signs that the violence in the country may be plummeting. But if voters want the PRI back, it is because "the alternatives [were] weak".[50] The newspaper also alleges that Mexico's preferences should have gone left-wing, but the candidate that represented that movement – Andrés Manuel López Obrador – was seen with "disgraceful behaviour". The conservative candidate, Josefina Vázquez Mota, was deemed worthy but was considered by The Economist to have carried out a "shambolic campaign". Thus, Peña Nieto wins by default, been considered by the newspaper as the "least bad choice" for reform in Mexico.[50]

Aftermath of the return of the PRI and public reception

When it was tossed from the presidency in the year 2000, few expected that the "perfect dictatorship", a description coined by Mario Vargas Llosa, would return again in only 12 years.[51] Associated Press published an article on July 2012 noting that many immigrants living in the United States were worried about the PRI's return to power and that it could dissuade many from returning to their homeland.[52] The vast majority of the 400,000 voters outside of Mexico voted against Peña Nieto, and said they were "shocked" that the PRI – which largely convinced them to leave Mexico – had returned.[52] Voters that favored Peña Nieto, however, believed that the PRI "had changed" and that more jobs would be created under the new regime.[53] Moreover, some U.S. officials were concerned that Peña Nieto's security strategy meant the return to the old and corrupt practices of the PRI regime, where the government made deals and turned a blind eye on the cartels in exchange for peace.[54] After all, they worried that Mexico's drug war, which had already cost over 50,000 lives, would make Mexicans question on why they should "pay the price for a US drug habit".[54] Peña Nieto denied, however, that his party would tolerate corruption, and stated he would not make deals with the cartels.[54] In spite of Peña's words, a pool from September 20, 2016, revealed that 83% of Mexican citizens perceived the PRI as the most corrupt political party in Mexico.[55]

The return of the PRI brought some perceived negative consequences, among them:

- Low levels of presidential approval of EPN and allegations of presidential corruption: The government of president of Mexico Enrique Peña Nieto (EPN) has faced multiple scandals, and allegations of corruption. Reforma who has run a surveys of presidential approval since 1995, revealed EPN had received the lowest presidential approval in modern history since they started surveying about it in 1995. Revealed EPN had received a mere 12% approval rating. The lowest since they started to survey for presidential approval, the second lowest approval was for the Ernesto Zedillo (1994-2000) also from the PRI. While also revealing both presidents elected from National Action Party (PAN), Vicente Fox (2000-2006) and Felipe Calderon (2006-2012), both had higher presidential approvals than the PRI presidents.[56]

- PRI corrupt ex-governors declared criminals by the Mexican government: During EPN's government multiple members of the PRI political party have been declared criminals by the Mexican government, specially alarming the fact that many of those PRI members in fact campaigned with the PRI, and in fact where elected as state governors within the Mexican government, among those are: the aforementioned Tomas Yarrington from Tamaulipas (along his predecessor Eugenio Hernandez Flores), Javier Duarte from Veracruz,[57] César Duarte Jáquez from Chihuahua[58] (no family relation between both Duarte), and Roberto Borge from Quintana Roo, along their unknown multiple allies who enabled their corruption.[59] All those supported (or campaigned for state governors) EPN during his presidential campaign.[60][61][62]

- State of Mexico allegations of electoral fraud (2017): The 2017 elections within the state of Mexico were highly controversial, with multiple media outlet feeling there was electoral fraud committed by the PRI. In November 2017, magazine Proceso published an article accusing the PRI of breaking at least 16 state laws during the elections, which were denounced 619 times. They said that all of them were broken in order to favor PRI candidate for governor Alfredo del Mazo (whom is the cousin of Enrique Peña Nieto and whom several of his relatives have also been governors of said entity). The article claims it has been the most corrupt election in modern Mexican history, and directly blames the PRI. Despite all the evidence, Alfredo del Mazo was declared winner of the election by the electoral tribunals, and is currently serving as governor.[63]

The Chamber of Deputies also suffered from controversies from members of the PRI:

- Law 3 of 3 Anticorruption controversy: In early 2016, a controversy arose when all the Senate disputes from the PRI, voted against the "Ley 3 de 3 (Law 3 of 3)". A law that would have obligated every politician to declare three things: make an obligatory public patrimonial declaration, interests declaration, and fiscal. A light version of the law was accepted but it doesn't oblige politicians to declare.[64][65] While it was completely legal for the deputies from the PRI, to vote against such law, some news media outlets interpreted the votes against the promulgation of such law as the political party protecting itself from the findings that could surface if such declarations were to be made.[66][67]

- In November 2017, Aristegui Noticias reported that "the PRI and their allies were seeking to approve the "Ley de Seguridad Interior (Law of Internal Security)". Whom the Mexican National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) had previously said, that it violated Human Rights, because it favors the discretional ussage of the army forces. Endangering citicenz by giving a blank check to the army" and the president, to order an attack towards any group of people they consider a danger without requiring an explanation. This could include people such as social activists.[68][69]

Presidential campaign 2018

On November 27, 2017, Meade announced he would compete in the 2018 presidential election, representing the PRI. He has been reported to have been handpicked directly by president Enrique Peña Nieto through the controversial practice known as "El Dedazo" (the literal translation would be "The big finger", the slang phrase regards towards the incumbent president directly pointing towards his successor).[70][71]

Warnings towards the possibility of the PRI committing electoral fraud

Following the serious allegations of electoral fraud, concerning the election of Enrique Peña Nieto's cousin Alfredo del Mazo Maza as governor of the state of Mexico, in December 2017, Mexican newspaper Regeneración (which is officially linked to the MORENA party) warned about the possibility of the PRI committing an electoral fraud on the presidential election, citing the controversial law of internal security that the PRI senators approved as the means to diminish the protests towards such electoral fraud.[72] The website Bloomberg also supported that possible outcome, with Tony Payan, director of the Houston's Mexico Center at Rice University's Baker Institute, suggesting that both vote buyout and computer hackings were possible, citing the 1988 previous electoral fraud committed by the PRI. Bloomberg's article also suggested Meade could also receive unfair help from the over-budget amounts of money spent in publicity by incumbent president Enrique Peña Nieto (who also campaigned with the PRI).[73] A December 2017 article of The New York Times reported Peña Nieto spending about 2,000 million dollars on publicity during his first 5 years as president, the largest publicity budget ever spent by a Mexican President. Additionally, the article mentioned concerns about 68 percent of news journalists admitting to not believe to have enough freedom of speech. To support the statement, the article mentioned the time award-winning news reporter Carmen Aristegui was controversially fired shortly after revealing the Mexican White House scandals (concerning a conflict of interest regarding a house owned by Enrique Peña Nieto).[74]

Collaboration with Cambridge Analytica

After the Facebook scandal involving Cambridge Analytica in the United States presidential election, in April 2018, Forbes published the British news program Channel 4 News had mentioned the existence of proof revealing ties between the PRI and Cambridge Analytica, suggesting a "modus operandi" similar to the one in the United States. The information said they worked together at least until January 2018.[75][76][77] An investigation was requested, unlike the previous allegations of Russian and American intervention, there seems to be actual proof.[78] The PRI has denied ever contracting Cambridge Analytica.[79] The New York Times acquired the 57 page proposal of Cambridge Analytica's proposed collaboration strategy to benefit the PRI by hurting MORENA's candidate Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the political party rejected the offer but still paid Cambridge Analytica to not help the other candidates.[80]

Loss of power

On the 2018 election, Meade and the PRI suffered a monumental defeat. The candidate and the political party did not win majority of votes within any of the 300 voting locations around the 32 states of Mexico, losing to other political parties. The PRI was also defeated, on each of the 9 elections for state governors where the National Regeneration Movement won 4, PAN 3, and Social Encounter Party and Citizens' Movement each with 1.[81]

Electoral history

Presidential elections

| Election year | Candidate | Votes | % | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1929 | Pascual Ortiz Rubio | 1,947,848 | 93.6 | as PNR. The opposition candidate José Vasconcelos claimed victory for himself and refused to recognize the official results, claiming that the elections were rigged; then he unsuccessfully attempted to organize an armed revolt. He was jailed and later exiled to the United States. | |

| 1934 | Lázaro Cárdenas | 2,225,000 | 98.2 | as PNR | |

| 1940 | Manuel Ávila Camacho | 2,476,641 | 93.9 | as PRM. The opposition candidate Juan Andreu Almazán refused to recognize the official results, claiming that a massive electoral fraud had taken place. He later fled to Cuba and unsuccessfully tried to organize an armed revolt. | |

| 1946 | Miguel Alemán Valdés | 1,786,901 | 77.9 | ||

| 1952 | Adolfo Ruiz Cortines | 2,713,419 | 74.3 | The opposition candidate Miguel Henríquez Guzmán claimed victory and refused to recognize the official results, claiming that a massive electoral fraud had taken place. | |

| 1958 | Adolfo López Mateos | 6,767,754 | 90.4 | ||

| 1964 | Gustavo Díaz Ordaz | 8,368,446 | 88.8 | ||

| 1970 | Luis Echeverría Álvarez | 11,970,893 | 86.0 | ||

| 1976 | José López Portillo | 16,727,993 | 100.0 | unopposed | |

| 1982 | Miguel de la Madrid | 16,748,006 | 74.3 | ||

| 1988 | Carlos Salinas de Gortari | 9,687,926 | 50.7 | All of the opposition candidates claimed that the election was rigged and refused to recognize the official results; Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas and Manuel Clouthier both claimed victory. | |

| 1994 | Ernesto Zedillo | 17,181,651 | 48.6 | ||

| 2000 | Francisco Labastida | 13,579,718 | 36.1 | ||

| 2006 | Roberto Madrazo | 9,301,441 | 22.2 | Coalition: Alliance for Mexico | |

| 2012 | Enrique Peña Nieto | 19,226,284 | 38.2 | Coalition: Commitment to Mexico | |

| 2018 | José Antonio Meade | 9,289,378 | 16.4 | Coalition: Todos por México |

Congressional elections

Chamber of Deputies

| Election year | Constituency | PR | # of seats | Position | Presidency | Note | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| votes | % | votes | % | ||||||

| 1940 | 172 / 173 |

Majority | Manuel Ávila Camacho | ||||||

| 1946 | 1,687,284 | 73.5 | 141 / 147 |

Majority | Miguel Alemán Valdés | ||||

| 1952 | 2,713,419 | 74.3 | 151 / 161 |

Majority | Adolfo Ruiz Cortines | ||||

| 1958 | 6,467,493 | 88.2 | 153 / 162 |

Majority | Adolfo López Mateos | ||||

| 1964 | 7,807,912 | 86.3 | 175 / 210 |

Majority | Gustavo Díaz Ordaz | ||||

| 1970 | 11,125,770 | 83.3 | 175 / 210 |

Majority | Luis Echeverría Álvarez | ||||

| 1976 | 12,868,104 | 85.0 | 195 / 237 |

Majority | José López Portillo | ||||

| 1982 | 14,501,988 | 69.4 | 14,289,793 | 65.7 | 299 / 400 |

Majority | Miguel de la Madrid | ||

| 1988 | 9,276,934 | 51.0 | 9,276,934 | 51.0 | 260 / 500 |

Majority | Carlos Salinas de Gortari | ||

| 1991 | 14,051,349 | 61.4 | 14,145,234 | 61.4 | 320 / 500 |

Majority | Carlos Salinas de Gortari | ||

| 1994 | 16,851,082 | 50.2 | 17,236,836 | 50.3 | 300 / 500 |

Majority | Ernesto Zedillo | ||

| 1997 | 11,305,957 | 39.1 | 11,438,719 | 39.1 | 239 / 500 |

Minority | Ernesto Zedillo | ||

| 2000 | 13,720,453 | 36.9 | 13,800,306 | 36.9 | 207 / 500 |

Minority | Vicente Fox | ||

| 2003 | 6,166,358 | 23.9 | 6,196,171 | 24.0 | 224 / 500 |

Minority | Vicente Fox | ||

| 2006 | 11,629,727 | 28.0 | 11,689,110 | 27.9 | 121 / 500 |

Minority | Felipe Calderón | Coalition: Alliance for Mexico | |

| 2009 | 12,765,938 | 36.9 | 12,809,365 | 36.9 | 241 / 500 |

Minority | Felipe Calderón | ||

| 2012 | 15,166,531 | 31.0 | 15,513,478 | 31.8 | 212 / 500 |

Minority | Enrique Peña Nieto | Coalition: Commitment to Mexico | |

| 2015 | 11,604,665 | 34.2 | 11,638,556 | 29.2 | 203 / 500 |

Minority | Enrique Peña Nieto | Coalition: Commitment to Mexico | |

| 2018 | 42 / 500 |

Minority | Andrés Manuel López Obrador | Coalition: Todos por México | |||||

Senate elections

| Election year | Constituency | PR | # of seats | Position | Presidency | Note | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| votes | % | votes | % | ||||||

| 1964 | 7,837,364 | 87.8 | 64 / 64 |

Majority | Gustavo Díaz Ordaz | ||||

| 1970 | 11,154,003 | 84.4 | 64 / 64 |

Majority | Luis Echeverría Álvarez | ||||

| 1976 | 13,406,825 | 87.5 | 64 / 64 |

Majority | José López Portillo | ||||

| 1982 | 63 / 64 |

Majority | Miguel de la Madrid | ||||||

| 1988 | 9,263,810 | 50.8 | 60 / 64 |

Majority | Carlos Salinas de Gortari | ||||

| 1994 | 17,195,536 | 50.2 | 95 / 128 |

Majority | Ernesto Zedillo | ||||

| 1997 | 11,266,155 | 38.5 | 77 / 128 |

Majority | Ernesto Zedillo | ||||

| 2000 | 13,699,799 | 36.7 | 13,755,787 | 36.7 | 51 / 128 |

Minority | Vicente Fox | ||

| 2006 | 11,622,012 | 28.1 | 11,681,395 | 28.0 | 39 / 128 |

Minority | Felipe Calderón | Coalition: Alliance for Mexico | |

| 2012 | 18,477,441 | 37.0 | 18,560,755 | 36.9 | 61 / 128 |

Minority | Enrique Peña Nieto | Coalition: Commitment to Mexico | |

| 2018 | 14 / 128 |

Minority | Andrés Manuel López Obrador | Coalition: Todos por México | |||||

Controversies

Vote-buying

Due to weak law enforcement and weak political institutions, vote-buying and electoral fraud are a phenomenon that typically does not see any consequences. As a result of a pervasive, tainted electoral culture, vote buying is common among major political parties that they sometimes reference the phenomenon in their slogans, "Toma lo que los demás dan, ¡pero vota Partido Accion Nacional!"(English: Take what the others give, but vote National Action Party!)[82][83]

In popular culture

Film depiction

The perceived political favoritism of Televisa towards the PRI, and the concept of the "cortinas de humo (smoke screens)" was explored in the Mexican black-comedy film The Perfect Dictatorship (2014), directed and written by Luis Estrada, whose plot directly criticizes both the PRI and Televisa.[84] Taking place in a Mexico with a tightly controlled media landscape, the plot centers around a corrupt politician (a fictional stand-in for Enrique Peña Nieto) from a political party (serving as a fictional stand-in for the PRI), and how he makes a deal with TV MX (which serves as a stand-in to Televisa) to manipulate the diffusion of news towards his benefit, in order to save his political career.[85] The director made it based on the perceived media manipulation in Mexico.[86]

See also

References

- ↑ José Antonio Aguilar Rivera (August 31, 2016). "Nota sobre el nacionalismo claudicante". Nexos.

- ↑ Laura Rojas (August 17, 2014). "La muerte del nacionalismo revolucionario". Excélsior.

- ↑ Juan Jose de la Cruz Arana (February 16, 2012). "Autoridad y Memoria: El Partido Revolucionario Institucional". Distintas Latitudes.

- ↑ Carlos Báez Silva (May 2001). El Partido Revolucionario Institucional. Algunas Notas sobre su Pasado Inmediato para su Comprensión en un Momento de Reorientación. Los Años Recientes (PDF). Convergencia. pp. 5, 6. ISSN 1405-1435.

- ↑ Daniel Bonilla Maldonado (April 18, 2016). El constitucionalismo en el continente americano. Siglo del Hombre. pp. 2019, 220.

- ↑ Francisco Paoli Bolio (2017). Constitucionalismo en el siglo XXI (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México.

- ↑ Graham, Dave (4 July 2018). "RIP PRI? Mexico's ruling party in 'intensive care' after drubbing". Reuters. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ↑ Bruhn, Kathleen (2008), Urban Protest in Mexico and Brazil, Cambridge University Press, p. 18

- ↑ Storrs, K. Larry (2005), "Mexico-U.S. Relations", Mexico: Migration, U.S. Economic Issues and Counter Narcotic Efforts, Stanford University Press, p. 56

- ↑ Samuels, David J.; Shugart, Matthew S. (2010), Presidents, Parties, and Prime Ministers: How the Separation of Powers Affects Party Organization and Behavior, Cambridge University Press, p. 141

- 1 2 "Full Member Parties". Socialist International. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ↑ "Meade, the King of the Mexican Sandwich". El Universal. January 11, 2018.

- 1 2 Russell, James W. (2009). Class and Race Formation in North America. University of Toronto Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8020-9678-4.

- ↑ Kopstein, Jeffrey; Lichbach, Mark; Hanson, Stephen E. (July 21, 2014). Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing Global Order. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ MacLeod, Dag (2005). Downsizing the State: Privatization and the Limits of Neoliberal Reform in Mexico. Penn State Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 0-271-04669-4.

- 1 2 "Vargas Llosa: "México es la dictadura perfecta"". El País (in Spanish). 1 September 1990.

- ↑ Bay, Austin (July 4, 2012). "A New PRI or the Old PRI in Disguise?". Real Clear Politics. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ↑ Jackson, Allison (July 1, 2012). "Mexico elections: Voters could return Institutional Revolutionary Party to power". Global Post. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- 1 2 Gallo, Rubén (2004). New Tendencies in Mexican Art: The 1990s. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 135–136. ISBN 9781403982650. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "The Mexican Revolution - Consolidation (1920–40) Part 2". Mexconnect. October 9, 2008.

- ↑ "The Foundation of the PRI". mx.geocities.com (in Spanish). October 13, 2000. Archived from the original on October 25, 2009.

- ↑ Lucas, Jeffrey Kent (2010). The Rightward Drift of Mexico’s Former Revolutionaries: The Case of Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press. pp. 171–203. ISBN 978-0-7734-3665-7.

- ↑ Crandall, R. (2004). "Mexico's Domestic Economy". In Crandall, Russell; Paz, Guadalupe; Roett, Riordan. Mexico's Democracy at Work: Political and Economic Dynamics. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Reiner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58826-300-1.

- ↑ Julia Preston; Samuel Dillon (2005). Opening Mexico: The Making Of A Democracy. Macmillan. pp. 54–184. ISBN 978-0-374-52964-2.

- ↑ Doyle, Kate (October 10, 2003). "The Tlatelolco Massacre". National Security Archive.

- ↑ "Documents link past presidents to CIA". El Universal. 20 October 2006. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009.

- ↑ "1968: Student riots threaten Mexico Olympics". BBC News. October 2, 1968.

- ↑ Schmidt, Henry (Summer 1985). "The Mexican Foreign Debt and the Sexennial Transition from López Portillo to de la Madrid". Mexican Studies. 1 (2): 227–285.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 Doyle, Kate (March 14, 2004). "Prelude to Disaster: José López Portillo and the Crash of 1976". National Security Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Biography of José López Portillo". Memoria Política de México.

- ↑ "¿Qué es la COPPPAL?". COPPPAL.org (in Spanish).

- ↑ "Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas Solórzano". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Thompson, Ginger (9 March 2004). "Ex-President in Mexico Casts New Light on Rigged 1988 Election". The New York Times.

- ↑ Rascón, Marco (18 July 2006). "1988". La Jornada (in Spanish).

- 1 2 "Biography of Manuel Clouthier". Memoria Política de México.

- 1 2 "Partido Revolucionario Institucional". NNDB. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Los "cuatro fantásticos" del PRI, listos para las urnas". El Mundo (in Spanish). 4 November 1999. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009.

- ↑ "What Elba Esther Gordillo's Arrest Means". ABC News. March 4, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Integrantes del Tucom, de políticos pobres a precandidatos que gastan millones". La Jornada (in Spanish). 25 July 2005. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011.

- ↑ Goi, Leonardo; Dudley, Steven (April 13, 2017). "An Extradition from Italy May Increase US-Mexico Tensions". InsightCrime.org. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ PGR México [@PGR_mx] (8 January 2017). "#Recompensa ¿Tienes información que ayude a la localización y aprehensión de #TomásYarrington?" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ↑ "Expulsa PRI de sus filas a Tomás Yarrington". El Universal (in Spanish). 16 December 2016.

- ↑ "Montiel deja vía libre a Madrazo". El Universal (in Spanish). October 21, 2005.

- ↑ "Madrazo Set to Win PRI Presidential Primary". Los Angeles Times. November 14, 2005.

- ↑ "AMLO, "primo hermano": Chuayffet". La Jornada (in Spanish). March 15, 2006.

- ↑ "El Movimiento". elmovimiento.org. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

- ↑ "Concluye cómputo municipal y distrital en Chiapas". El Universal (in Spanish). 12 October 2007.

- ↑ "Mexico's ruling party loses midterm elections". CNN. July 7, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ↑ Sanchez, Raf (2 July 2012). "Mexico elections: Enrique Peña Nieto pledges a new era". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Mexico's presidential election: Back to the future". The Economist. 23 June 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ "Mexico's election: The PRI is back". The Economist. 2 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- 1 2 Watson, Julie (July 2, 2012). "Immigrants express shock at return of Mexico's PRI". The Huffington Post. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ↑ Castillo, E. Eduardo; Corcoran, Katherine (1 July 2012). "Mexico Elections: PRI Could Return To Power With Pena Nieto As President". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 Carroll, Rory (2 July 2012). "US concerned Mexico's new president may go easy on drug cartels". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ Digital, Milenio. "PRI, el más corrupto según encuesta de percepción". milenio.com. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ Ortiz, Erik (August 31, 2016). "Why Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto is so unpopular". NBC News. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ McDonnell, Patrick J. "Former governor of Mexico's Veracruz state extradited from Guatemala to face corruption charges". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Mexico: Ex-governor flees to Texas to evade corruption allegations". The Dallas Morning News. March 30, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "PGR e Interpol capturan a Roberto Borge en Panamá". El Universal. June 5, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Corrupción envuelve a 11 exgobernadores". Excélsior. April 17, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ Malkin, Elisabeth (April 19, 2017). "En México se acumulan los gobernadores corruptos, e impunes". The New York Times (in Spanish). Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Conoce a los 11 exgobernadores más corruptos de México". Regeneracion.mx. April 17, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ ""Ni libre, ni auténtica", la elección en Edomex: Ni un Fraude Más". Proceso. November 16, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Discusión en el senado". Ley 3de3. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Aprueba el Senado versión 'light' de la 'Ley 3 de 3'". La Jornada (in Spanish). 15 June 2016.

- ↑ "Ley #3de3 avanza en comisiones del Senado; PAN vota a favor". El Financiero (in Spanish). 14 June 2016.

- ↑ "Nuevamente el PRI vota en contra de de los ciudadanos: PAN BCS". El Informante - Baja California Sur (in Spanish). 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Aristegui Noticias on Twitter". twitter.com. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Más poder al Presidente y a las Fuerzas Armadas: las entrañas de la Ley de Seguridad Interior". Aristegui Noticias.com. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Meade es el dedazo de siempre, dice Barrales". El Universal. November 27, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Código Alfa: La estrategia del dedazo en la precandidatura de Meade". SDP Noticias.com. December 4, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "PRI prepara un fraude electoral en 2018, alertan académicos y expertos". Regeneracion.mx. December 25, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Mexico's Presidential Election Could Get Really Dirty". Bloomberg.com. December 18, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ Ahmed, Azam (December 25, 2017). "Con su enorme presupuesto de publicidad, el gobierno mexicano controla los medios de comunicación". The New York Times (in Spanish). Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ↑ Staff, Forbes (March 30, 2018). "Cambridge Analytica trabajó con el PRI: Channel 4 News • Forbes México". forbes.com.mx.

- ↑ Murillo, Javier. "Cambridge Analytica, sigan la ruta del dinero". elfinanciero.com.mx.

- ↑ Peinado, Fernando; Palomo, Elvira; Galán, Javier (March 22, 2018). "The distorted online networks of Mexico's election campaign" – via elpais.com.

- ↑ "Exigen al INAI investigar a Cambridge Analytica, Facebook y desarrolladoras de Apps en México - Proceso". proceso.com.mx. April 2, 2018.

- ↑ http://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/niega-pri-haber-contratado-a-cambridge-analytica/1229584

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/24/world/americas/mexico-election-cambridge-analytica.html

- ↑ https://www.animalpolitico.com/2018/07/morena-logra-5-de-9-gubernaturas-pri-pierde/

- ↑ http://www.latimes.com/world/la-fg-mexico-tortilla-war-20180228-story.html

- ↑ http://www.excelsior.com.mx/opinion/leo-zuckermann/2017/05/24/1165328

- ↑ Maraboto, Mario (28 October 2014). "'La dictadura perfecta': más allá de la película". Forbes Mexico.

- ↑ Ríos, Sandra. "Mexican Film 'La dictadura perfecta' ("The Perfect Dictatorship") Depicts Mexican Reality". Atención San Miguel.

- ↑ Linthicum, Kate (November 3, 2014). "Mexican filmmaker Luis Estrada's satirical agenda hits home". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). |